The Birth of the USPS and the Politics of Postal Reform

Fifty years ago, President Richard Nixon signed into law the Postal Reorganization Act, the landmark law that created the United States Postal Service (USPS). The law walked a difficult tightrope — creating a postal network that operated as both a business and public service. Today, as the fate of the USPS hangs in the balance, we’re featuring an excerpt from “Letters, Power Lines, and Other Dangerous Things: The Politics of Infrastructure Security” that looks back at the creation of the USPS and reveals how it transformed postal politics for good — and for ill.

“Our present postal system is obsolete; it has broken down; it is not what it ought to be for a nation of 200 million people.… And now is the time to act.“

—President Richard Nixon, 1969

On September 2, 1969, President Nixon held a short press conference at his San Clemente, California, home. The press conference was organized to push for a seemingly impossible task: postal reform. Standing to Nixon’s right, in a show of bipartisan support, was Lawrence O’Brien. Nixon and O’Brien did not agree on much. O’Brien was the consummate Democratic Party insider — he had run President Kennedy’s Senate and presidential campaigns; had served as a special assistant for congressional relations in both the Kennedy and Johnson administrations; had headed the Democratic National Committee in 1968; had overseen the Post Office Department as postmaster general under President Johnson; and had run Robert Kennedy’s ill-fated presidential campaign — and a natural adversary for Nixon.

Yet on the issue of postal reform, Nixon and O’Brien agreed: Something had to be done. During his first term, President Nixon made postal reform a key priority. He sought to restructure the Post Office Department in a manner that would relax, if not entirely remove, political oversight and push postal service toward a more business-like footing. In an effort to build support for legislative reform, Nixon successfully prodded O’Brien to cochair the Citizens Committee for Postal Reform, a newly formed lobbying organization dedicated to pursuing legislative change. Like Nixon, O’Brien supported overhauling the Post Office Department.

The San Clemente press conference was somewhat stilted. In his memoir, O’Brien recalls Nixon being uncertain as to whether he should call him “Larry” or “Mr. O’Brien” (he eventually settled on Larry). The press conference was designed to highlight the bipartisan support for reform, but the cause seemed doomed, or at least, unlikely to succeed. The Post Office Department was deeply entrenched in the day-to-day life of the nation and featured a bureaucracy made up of hundreds of thousands of federal employees. Reform was not a modest goal. As O’Brien wryly remarked during the press conference, “This bipartisan effort may continue forever.”

As O’Brien wryly remarked during the press conference, “This bipartisan effort may continue forever.”

Yet, despite O’Brien’s skepticism, postal reform would indeed come to pass. The Postal Reorganization Act (PRA) of 1970 would transform the Post Office Department into the United States Postal Service (USPS). The act kicked off a decade of infrastructure reorganization. Across seemingly all infrastructure sectors, political controls that had appeared stable gave way and were replaced with the logic of the market. O’Brien joined President Nixon for the ceremonial signing of the reorganization bill in August 1970. It was the second and last time O’Brien and Nixon would meet face-to-face. Their fates, however, would again intersect. In 1972 a watchman at the Watergate complex caught burglars breaking into O’Brien’s office. Agents working to reelect President Nixon had been tapping O’Brien’s phone at the Democratic National Committee headquarters (O’Brien was again serving as chairman for the Democratic National Committee). The ensuing scandal would eventually lead to President Nixon’s resignation in 1974.

The U.S. postal system was transformed by the creation of the USPS. For well over a century and a half, the cabinet-level Post Office Department ran the postal system. The postal system was an important and vital institution. As historians Richard John, David Henkin, and others have documented, public control over the postal system sparked multiple revolutions in communication during the late-18th and 19th centuries, first subsidizing the wide-circulation of information about public affairs across the nation and later enabling new forms of personal sociability cheap through cheap letter rates.

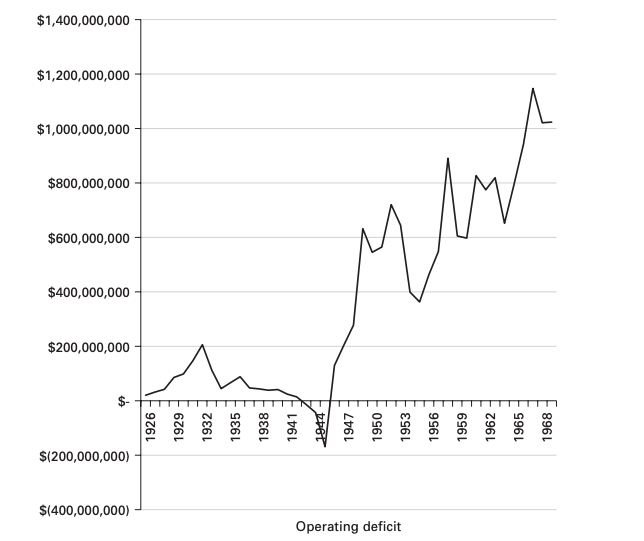

By the mid-1960s, however, the postal system was in serious trouble. The Post Office faced an economic and operational crisis characterized by rising costs, an expanding deficit, and declines in the quality of service. Post–World War II economic prosperity fed a spike in mail volume that overtaxed the postal infrastructure: Between 1945 and 1970, annual mail volume leaped from 37.9 billion to 84.8 billion pieces, and total postal costs ballooned from roughly $1.1 billion to $7.3 billion. Revenue, however, did not keep pace, rising from $1.1 billion to only $6.3 billion over the same period, leading the Post Office Department to accumulate a deficit in excess of $1 billion by the late 1960s.

As 10 million pieces of backlogged mail sat immobile in the office and in trailers lining the surrounding streets, management considered the drastic step of burning the accumulated mail in a desperate effort to “reset” the system.

The postal network was largely ill-equipped to handle the influx of volume and service suffered. Postal equipment had not been updated in decades, and the existing network of post offices was structured around increasingly obsolete rail lines, which made offices difficult to access via the now prominent modes of truck and air transportation. The dire state of affairs was given visible expression with the breakdown of the Chicago post office in 1966. As 10 million pieces of backlogged mail sat immobile in the office and in trailers lining the surrounding streets, management considered the drastic step of burning the accumulated mail in a desperate effort to “reset” the system.

Office Department accumulated a deficit in excess of $1 billion.

To Postmaster General Lawrence O’Brien, the breakdown was symptomatic of a larger looming crisis: Increasing volume, rising costs and deficits, and outmoded infrastructure and technology would make large-scale breakdowns like Chicago the norm. In his estimation, the postal system was in a “race with catastrophe,” and regulatory reform provided the only answer. O’Brien pressed the issue of comprehensive postal reform during his tenure in office, over the reluctance of President Johnson, and secured the creation of a presidential commission to examine and offer recommendations on postal reform in 1967.

The commission, known as the Kappel Commission after its chairperson, former head of AT&T Frederick Kappel, released its final report in 1968 and provided the basic outlines for reform legislation. As the cochair of the bipartisan Citizens Committee for Postal Reform, O’Brien was able to secure a comment in support of postal reform in President Johnson’s farewell address and worked in tandem with President Nixon’s postmaster general Winton Blount to advance the Kappel Commission’s recommendations.

Postal reform was initially framed as a way of removing the deleterious effects of “politics” on postal affairs and enhancing the autonomy of postal management. In time, however, it would prove to do neither.

Reform faced an uphill battle. The idea of reforming the basic structure of the postal system was not new. Periodically, different groups had agitated for dramatic reform. Nor was a postal deficit unprecedented; though the deficit spiked during the 1960s, revenue shortfalls had been the norm for over a century.

Historically, however, a host of complementary institutions supported the status quo and blunted calls for comprehensive change. The unique form of postal service created in fits and starts during the late 18th and 19th centuries became invested in other mutually supporting institutions. The publishing industry, political campaigns, and national voluntary associations all relied on cheap second-class postage for their operation, while political parties relied on the dispensing of local postmasterships as a key source of political patronage. In each instance these interests provide a key source of “feedback” supporting the continuation of the postal status quo. This mutual support, as much as ideological commitment to an ideal of service, helped ward off comprehensive reform.

By the late 1960s, postal reform appeared to be an attractive way for Congress and the executive branch to divest themselves from the headaches and diminishing benefits that flowed from involvement in postal politics.

This matrix of support was, however, fragile and contingent. Most importantly, during the 20th century the tight connection between the postal bureaucracy and partisan politics frayed. Carriers and clerks were placed under the civil service system (as opposed to postmasters, who were still political appointees) and became an independent, unionized political force that agitated for better working conditions and wage increases. The growing activism of labor transformed the relationship between partisan politics and hence Congress and postal labor: The postal workforce morphed from a political resource into a liability. By the late 1960s, postal reform appeared to be an attractive way for Congress and the executive branch to divest themselves from the headaches and diminishing benefits that flowed from involvement in postal politics.

Through tense negotiations with mailers and labor, the Nixon administration secured the passage of the PRA. Critically, postal unions, initially a key roadblock to passing reform legislation, agreed to throw their support behind reorganization in exchange for wage increases and binding arbitration. Commercial mailers also came onboard once former postmaster general O’Brien, current postmaster general Blount, and the Nixon administration put their weight behind reform, and regulatory restructuring appeared to be a real possibility. The promise of reducing postal costs served as a carrot for mailers leery of losing generous rates in the face of escalating costs and declining service.

The PRA transferred the operation of the postal system from the cabinet-level Post Office Department to a new independent government establishment (USPS). Quickly, however, reorganization took on a life of its own. Through a series of administrative hearings and decisions, postal rates were largely recast according to market factors, and large portions of the postal network were effectively liberalized. Ironically, these changes wound up circumscribing the power of managers in key respects and empowered well-organized commercial mailers to assume a dominant role in postal politics.

The Postal Reorganization Act of 1970

The Kappel Commission’s report provided the basic blueprint for the PRA, and its recommendations were eventually written into law. The problem hampering the postal system, according to the commission: “politics.” The fracturing of authority between different congressional committees and the executive branch meant that postal managers had no practical control over costs, revenue, or investment. Rates were kept low, while congress refused to allow postal managers to invest in new automation or mechanization technologies. Political expedience continually won out over sound business discretion and economic data. The commission recommended transforming the Post Office Department into an independent, self-supporting corporation owned by the federal government. The postal corporation, as the commission called it, would be free to open and close offices; set rates in accordance with sound data; study, borrow, and invest in new technologies; and operate with the efficiency and flexibility of a business. Postal management would be allowed to actually manage. The Kappel Commission argued that the reorganization of postal service into a business-like model would lead to the elimination of the postal deficit, lower rates, and improved service.

The problem hampering the postal system, according to the Kappel commission: “politics.”

The PRA abolished the cabinet-level Post Office Department and established USPS as an independent government agency and the Postal Rate Commission (PRC), a body to review postal rates and offer recommendations. The PRA also began the process of phasing out federal appropriations and required USPS to break even. A new Board of Governors would head USPS and be subject to staggered appointment (to ensure that no single president could stack the board). USPS would operate with little direct congressional oversight; it could initiate rate increases, borrow up to $15 billion, invest in new technologies and improvements as it saw fit, and, it appeared, generally operate with a more or less free hand. Some general language, however, was written into the law noting the importance of rural service, equitable rates, and the continued support for cultural, literary, and informational content. Finally, the new PRC was to serve as a board of review to ensure that rates were fair, based on evidence, and set in accordance with the aims of the PRA.

The Politics of Postal Reform

The PRA transformed the basic outlines of postal governance by shifting authority from Congress to the newly created USPS. This transfer was intended to remake postal service in the guise of a typical business enterprise that could invest in new technologies, set rates, and define service at the discretion of the Board of Governors. Yet the PRA also included vague language acknowledging that the Postal Service did, indeed, have a public service mission and retained the Private Express Statutes (the laws that provided a government monopoly over certain aspects of the postal service). Sorting out how to reconcile these different aspects of postal service — how USPS would function as a business and a public service — was left muddled. This tension was worked out through a series of contentious landmark rate cases and administrative hearings during the 1970s and early 1980s.

The PRA did not, to be clear, eliminate politics from postal affairs; rather, it changed the venue within which different interest groups, including mailers and labor, fought over the manifestly political issues relating to cost and terms of service. Now, these debates occurred through formal rate cases and administrative hearings that featured arcane economic studies and precise legal justifications. It was here that postal reform proceeded, and the form and scope of the USPS would be defined.

Sorting out how to reconcile these different aspects of postal service — how USPS would function as a business and a public service — was left muddled.

Within these hearings and cases, a coalition of large-volume mailers attacked and helped discredit what had been the cornerstone of postal regulation for over a century, cross-subsidies between different forms of content, in favor of market prices. These attacks were enormously successful: They led not only to the transformation of how postal rates were thought of and designed but also to the liberalization of large portions of the postal network and the granting of a de facto veto for large-volume mailers in determining postal policy. In the drab language of economic theory and legal minutiae, substantial and dramatic changes to the constitution of postal service occurred. Congress had been an imperfect way of imposing public accountability upon the postal system. But reform would shift power toward large commercial mailers.

Reform was supposed to empower management, but this proved elusive. The rejection of cross-subsidies introduced new notions of discriminatory pricing into the setting of postal rates that in turn limited managerial autonomy. The impact would be far-reaching, affecting the Postal Service’s adoption of new information and communication technologies, and, more broadly, the balance of power within postal politics.

Over the next few decades, USPS would follow the wishes of larger commercial mailers. Management would pursue a narrow path — focusing on cutting costs through automation and the use of temporary, non-career, workers. More expansive efforts to grow the postal service, including the launch of an early form of email dubbed “E-COM,” were blocked.

Postal reformers had hoped that the creation of the USPS might provide a way to remove politics from the postal service. It was a failed effort — the postal service, like all public services, remains deeply entangled in politics. The choices it makes — who to serve, what to charge, what services to provide (and which to discontinue) — have far-reaching consequences. Postal reformers hoped that these decisions could be somehow placed outside of the machinations of politics. But, as the early maneuvering of large-volume mailers proved — and very recent events underline — politics and the postal service are inseparable.

Ryan Ellis is Assistant Professor of Communication Studies at Northeastern University and a previous recipient of the United States Postal Service’s Moroney Award for Scholarship in Postal History. He is the author of “Letters, Power Lines, and Other Dangerous Things: The Politics of Infrastructure Security” and co-editor of Rewired: Cybersecurity Governance.