What Broke the Age of Cheap Prices?

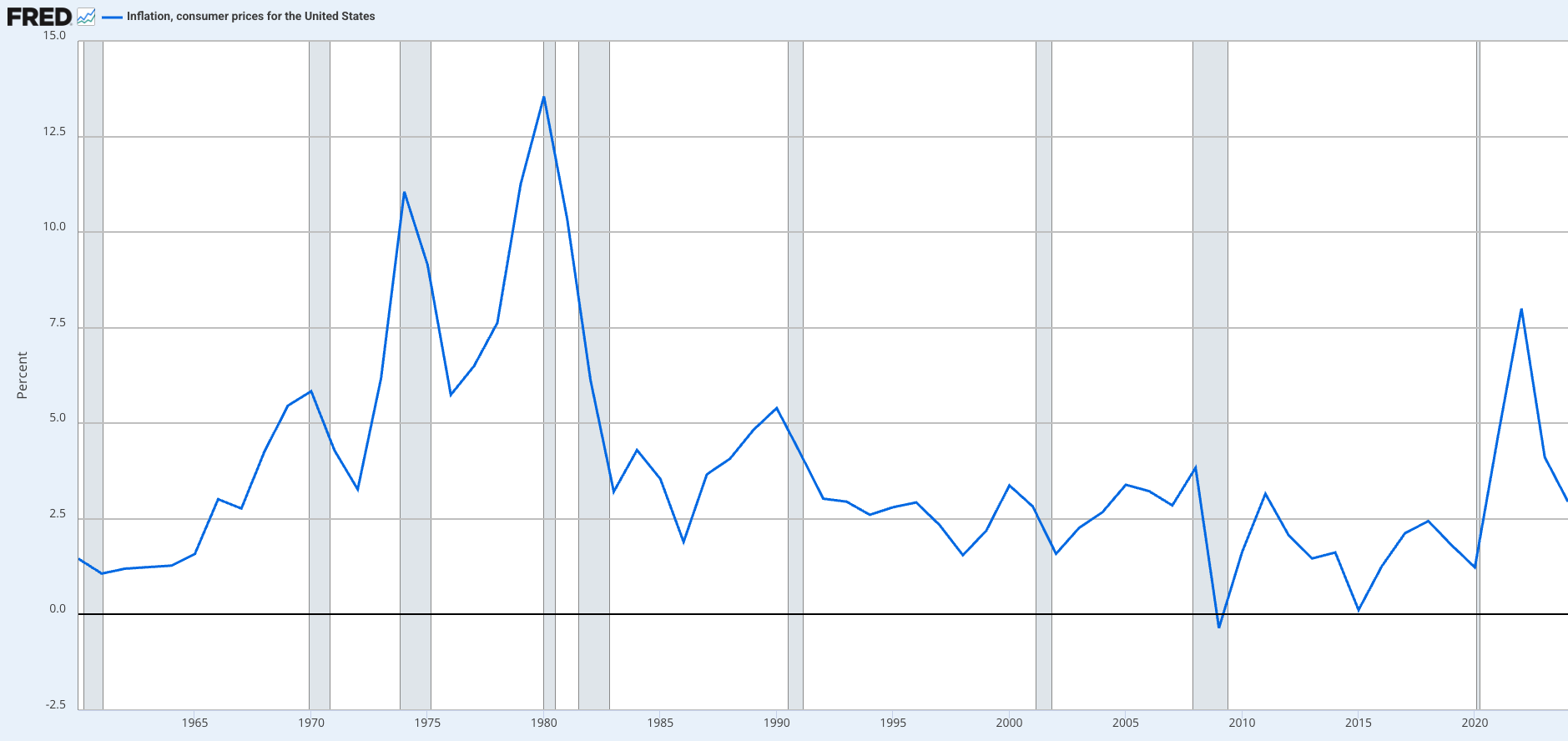

If you were born after the 1970s, chances are that you never gave inflation much thought until the COVID-19 crisis. And with good reason: Prices rose so slowly and steadily for decades after the Carter era that barely anyone noticed.

The pandemic changed that. Supply shocks, stimulus spending, and pent-up demand triggered painful price increases for everything from groceries and cars to gas and rent. Sticker shock was system-wide, and suddenly inflation went from a wonky academic subject to an electrifying national debate: What causes it? And more importantly, what can we do to reverse it?

These are just a few of the questions economist Martha Olney explores in her new book “Inflation,” one of the latest releases in MIT Press’s “Essential Knowledge” series.

In an interview below, edited for length and clarity, Olney unpacks America’s recent economic hangover, the Fed’s anti-inflationary toolbox, and the potential impact of Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs. “I think that if the tariffs continue at the rates that they’re currently at and they don’t blink again,” Olney says, “we’re going to see price impacts.”

A good place to start is your line in the book about how inflation has been off most Americans’ radars for decades, until it suddenly returned in 2021 during the post-COVID economic hangover. You write, “For everyone under 60 who had lived in the United States since their teens, all they knew was decade upon decade of price stability.” What changed after COVID, and what happened in the US economy that caused prices to spiral out of control so quickly?

Martha: There were several things that we can point to. One was a series of supply disruptions associated with COVID. And so, you had factory shutdowns, disruptions to transportation, and a lot of things people would normally buy were simply unavailable because of the COVID-related shutdowns. That alone was going to put upward pressure on prices, and that happens around the globe.

Another thing was that we had a very generous fiscal policy in the wake of COVID. If you recall, we really wanted people to stay home, and we didn’t want them to feel a financial necessity to go to work. So, we had extremely generous unemployment insurance, where many people — particularly at the low end of the income scale — were making more per week on unemployment than they had when they were working. People accumulating that kind of money meant two things: One, a lot of people were able to pay down their credit card debt, and outstanding credit card debt fell for the first time in a very, very, very long time in the United States. Second, it meant that people were able to afford to buy the things that were available. So, on the one hand, you had shortages of supply associated with the shutdowns from COVID. And on the other hand, you had people with extra money to spend who were looking for places to spend the money. Those two things came together to put upward pressure on prices.

And then the other thing, which is much more background, is the understanding by central bankers of what makes their policy effective has completely changed.

The third thing that happened was that the types of goods people needed in the immediate work-from-home pivot were very specific. There was a spike in demand for ring lights, webcams, microphones, etc. Those spikes in demand came while those goods were unavailable.

And then what happened was, just when things were starting to settle down, Russia invaded Ukraine — and that put upward pressure on wheat and oil prices. Since it was part of the period when we were still recovering from COVID, it gets kind of wrapped up in the post-COVID period.

So, you’re describing an increase in demand for work-from-home-related goods. But at the same time, you’re describing a decrease in commuter-related expenses — gasoline, cars, and restaurant expenses. Why didn’t those two forces countervail each other to such an extent that inflation didn’t radically increase as it did?

Martha: In order for the two forces to countervail, you would’ve had to have decreases in prices in those other sectors. But you did not see price deflation across the board in any kind of sector. One other thing I didn’t mention was the avian flu; it was putting upward pressure on egg and chicken prices. People weren’t eating in restaurants, but they were spending more on home-cooked meals. There was still a demand for eggs, chicken, flour, sugar, and so on. There wasn’t a huge drop in demand for the kinds of goods that would bring down that overall average.

You talk a lot in the book about the lag between rising prices and rising incomes: That’s where people really feel the pain, the sticker shock. One thing I want to note, though, is that Americans have felt that pain for a while with respect to housing and healthcare, which have been outpacing incomes for a long time now, even with the Fed’s gradual adjustments. So how does the Fed begin to address something like that? Or is that more in the realm of fiscal policy?

Martha: The Fed, by and large, does not try to cater their policies to any particular sector. I mean, they know that by adjusting interest rates, they’re impacting first and foremost the sectors that are interest-sensitive. But it’s not like they are saying, “Well, let’s see if we can change this kind of interest rate, which affects this sort of demand, and not change this type.”

Occasionally, there have been times when the Fed has deliberately tried to manipulate short-term versus long-term interest rates. Overnight and three-month rates are what they usually focus on. And then they let the financial markets determine from there the two-year rate, the 10-year rate, the 30-year rate, etc. There have been times — very few — when the Fed has directly intervened in the longer-term market, like the 10-year or the 30-year market, but it’s just not very common: There was one in the wake of the global financial crisis. There was an Operation Twist in the 1960s.

So, there’s been a handful of times when the Fed has intervened to try to manipulate those long-term interest rates — not so much to get a person’s rental cost down, but to stimulate construction, the housing market, and get people back to work.

Which, in turn, can help ease the cost of housing and healthcare…

Martha: Yes.

So, monetary policy is a blunt tool rather than a scalpel. Of course, blunt tools can carry some big unintended consequences, especially an unequal distribution of impact. How do you think central bankers should think about minimizing those types of unintended costs, especially for Americans who are most vulnerable to job losses and price shocks?

Martha: I think two things.

In recent years, the Fed has been more explicitly conscious of the impact of its policies on different groups within society. Their approach to economics when I was growing up in the field — which centered on the “average person” — no longer dominates. The work I did in Chapter 1, where I talk about the impact of inflation on Black, Hispanic families, white low-income and high-income families, some of that research is being done at the Fed. So, there’s certainly an awareness of the disparate impact of monetary policy on different groups in society.

That said, at the end of the day, when they’re voting at the FOMC meeting, they’re voting on whether to increase, decrease, or maintain one particular interest rate. They know that, in doing so, their interest rate policy will have disparate impacts on different groups within society. But is their number one goal to minimize those disparate impacts? No. Their number one goal is to keep inflation under control and keep employment relatively high.

You talk about the ’70s a lot as one of the truly canonical episodes of sustained US inflation. What do you think was fundamentally different about that period versus today’s post-COVID era?

Martha: Yeah, a number of things are different between the seventies and now. On the one hand, in the ’70s, oil prices were driving a lot of the inflation, and oil mattered because it was the key input to production in a lot of sectors. It was the primary source of energy. This is a world without solar panels, wind turbines, and not a lot of hydro.

The early ’70s were also a time when the economy was not open in the way it is now. There were still fixed exchange rates with a lot of countries. We didn’t have the pattern of trade that we have now. There wasn’t the kind of international competition [we have now].

A third thing is that the Federal Reserve policy works through changes in interest rates, which impact the demand for the interest-sensitive sectors. The United States economy in the 1970s was much more goods-based. And today it’s a much more service-based economy. Interest rates are relevant to a much smaller share of the economy today than was the case in the 1970s.

Why aren’t services as sensitive to interest rates?

Martha: Sensitivity comes from borrowing. So, we typically don’t borrow to get our hair cut; we borrow to buy a car, to get appliances, to get a house. We don’t borrow for most services.

And then the other thing, which is much more background, is the understanding by central bankers of what makes their policy effective has completely changed. In the 1970s, there was more of a “go big or go home” kind of approach: For monetary policy to be effective, they felt like it had to be big, it had to be impactful, it had to be surprising. Today, central bankers understand that if they can provide forward guidance, if they can clearly articulate to businesses what it is they’re going to do under each of several circumstances, then they only need to change policy a little bit for it to be effective because people will know what it is they’re going to do and will behave accordingly.

I still feel like we’re in a stage where the big issue around the tariffs is the uncertainty.

I want to pivot to the current moment. One of the most consequential moves Donald Trump has made in his second term has been the imposition of sweeping tariffs, supposedly aimed at reducing America’s reliance on foreign goods. How would you expect a series of tariffs of this kind to affect the price level over the next few years?

Martha: So, one answer is the easy econ — that you would expect any sort of additional tax that’s paid by consumers to increase the prices that consumers pay. A tariff is simply a tax that is ultimately paid by consumers.

The next answer is that how much of any tax a consumer pays versus how much of it is paid by the seller depends upon a number of factors. For instance, is the good a necessity even if the prices go up? Or is it something that’s more of a want and less of a need, in which case I’m much more sensitive to price increases. How much tax is actually paid by consumers depends on the nature of the products being taxed or tariffed.

I still feel like we’re in a stage where the big issue around the tariffs is the uncertainty. It’s 32 percent today, 29 percent tomorrow, 92 percent on Friday, and back to 32 percent on Monday. So far, it seems that the consumers have largely been protected from the impact of the tariffs. Is that because of the nature of the goods? Or is it because of stockpiling? For instance, a lot of companies had already bought the toys they were going to sell at Christmas. And so, the tariffs didn’t impact the cost of things this December. But now that those businesses have worked their way through those stockpiles, we may start to see more price increases. Then it’s going to come down to how much competition the companies that are selling these goods face. Do they feel like they can raise the prices they charge their customers and not lose a whole lot of market share?

I’m in the camp of, I think we haven’t gotten there yet. I think that if the tariffs continue at the rates that they’re currently at and they don’t blink again and lower them back down to essentially zero-ish, we’re going to see price impacts, and I think we’ll see them here in 2026.

Martha Olney is a Teaching Professor Emerita from the Department of Economics at the University of California, Berkeley. She is the recipient of multiple teaching and mentorship awards, an elected member of the Society of Distinguished Fellows of the Economic History Association, and the author of “Inflation.”