The Soviet Union’s Desperate Efforts at Mind Control

The year that began with George Bush taking office as the 41st president of the United States turned out to be one of the most tumultuous in the 20th century; ultimately, it led to the end of the Cold War. Millions of people huddled in front of their television sets to witness political upheaval in the Eastern bloc: the dismantling of border facilities between Hungary and Austria, inoperative checkpoints in Czechoslovakia, and the dramatic fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989. News about protests in Tiananmen Square and the ensuing massacre prompted fascination, then outrage throughout the world. In contrast, reports that Soviet troops were withdrawing from Afghanistan occasioned jubilation and cheer.

So long as the Soviet Union remained standing, another image prevailed there. Although Channel One also issued reports about earthly events, it steered the attention of viewers — in a land that still comprised 15 republics — toward a series of transmissions that began with an initial broadcast at 8:30 pm, October 8, 1989, immediately after the evening news.

By imbibing “charged” water, spectators were told they would feel the effects of the therapeutic session until the next transmission.

“Relax, let your thoughts wander free,” said Anatoly Mikhailovich Kashpirovsky to the citizenry of the entire Soviet Union. Prior to this date, the speaker — a licensed physician — had worked as a clinical psychotherapist for two and a half decades. For two years, he had also provided his services to the national weightlifting team. After the Olympic Games in Seoul (1988) — dominated by the Soviet Union, which carried away 132 medals (including six gold medals in weightlifting) — Kashpirovsky’s psychic tunings achieved popularity far beyond the realm of sports. Now, the adjustments he had made in the psychophysical apparatus of athletes would calm a land beset by turbulence and heal the body politic by setting viewers’ minds to the state’s new goals.

Evidently, policies of reform — efforts to restructure the system with slogans of glasnost and perestroika — had failed to convince the public. It seemed the population was slowly waking up from a kind of trance and starting to realize what had been happening for the last few years; in the process, it came to recognize the gulf in the standard of living that gaped between the Soviet Union and the West, whose economic power controlled the world. Now, at this perilous juncture, a new force — one that was not manifestly political, but rather “therapeutic” — would restore the former state and rally the individual forces constituting the collective.

The Setting for Healing

The evening following the first of Kashpirovsky’s six transmissions, 70,000 people demonstrated in Leipzig chanting, “We are the people!” This was the first protest against the GDR regime on a mass scale since 1953. But as the event was brewing, millions of Soviet citizens sat watching television as a supposed miracle worker readied them to face the future:

You can leave your eyes open for a while. Have a look at your surroundings. There should be no pointed objects, and no fire. Your posture should be stable. If anyone is seriously ill—for example, suffering from epilepsy — please do not participate in our séance; simply turn off the television.

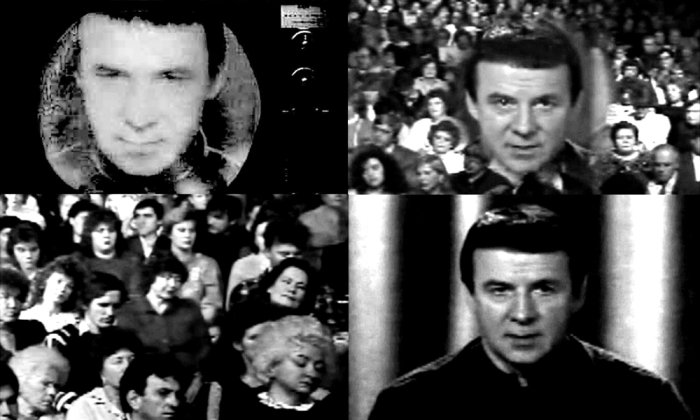

The first sequence of the 20-minute session showed Kashpirovsky speaking in close-up. Then, the image shifted to the site where events were taking place. Kashpirovsky stood at the podium of a cinema, broadcasting his therapeutic message to entranced audience members as lilting musical airs filled the room.

The iconography of the third, and final, sequence brought out the séance’s political dimensions. As the camera panned across the movie theater, the mesmerist’s face faded into, and over, the image. The effect was grotesque yet sublime: Like Leviathan, the sea monster of religious philosophy embodying state power in Thomas Hobbes’s political theory. Nor were effects meant to be limited to the sphere of images. By imbibing “charged” water, spectators were told they would feel the effects of the therapeutic session until the next transmission. At the beginning of the broadcast, Kashpirovsky instructed people seated at home to have a vessel filled with water at the ready; drinking it would revive the unconscious of the land, which had fallen ill, and instill the aims of communism in the popular mind yet again.

Kashpirovsky’s third transmission took place on November 5; the fourth occurred two weeks later. Between the two séances — on Friday, November 10 — Channel One reported that the Berlin Wall had been opened the previous evening. Both before and after this momentous event, audiences throughout the Soviet Union tuned in to be rewired and receive “star messages” so their faltering image of the world might come into focus again.

In the interference of a network where the symbolic, systematic, and rhetorical organization of data and information came into play, the specifically Soviet mode of historiographic representation was exposed: a coupling of material and immaterial practices meant to fuel the corporate enterprises of the Cold War. At the end of this confrontation of two systems, East and West — which each coordinated the assembled opinions of the public to strategic ends — people on the Soviet side sat engrossed by a televisual spiritist session: a miracle cure, technologically induced intoxication to dam up doubts and banish secret thoughts into the “iron cage of the unconscious.” Kashpirovsky’s transmission represents the last effort of Soviet power to initiate the citizenry into the mysteries of the communist apparatus that was in the course of disappearing.

Wladimir Velminski is a Head of the Project History and Theory of Media Regimes in Eastern Europe in the Department of Media Studies at the Bauhaus University Weimar. Previously, Velminski worked at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, at the Universität Zürich, and at ETH Zürich. This article is excerpted from his book “Homo Sovieticus: Brain Waves, Mind Control, and Telepathic Destiny.”