The Absence of Black Soldiers in Civil War Photos Speaks Volumes

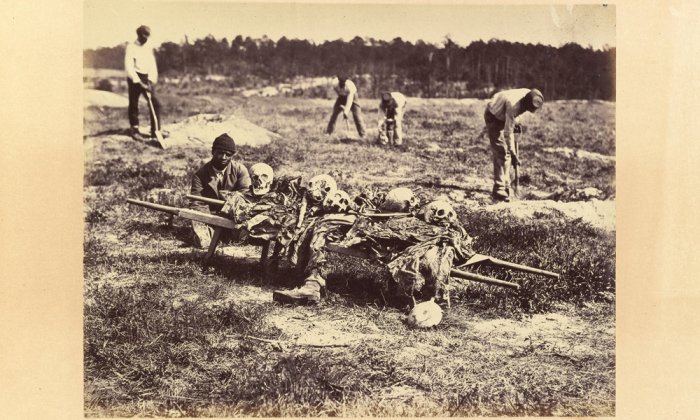

Five black men fill the photographic space with the visible labor their bodies represent. One stands, and three are bent over as they negotiate the Virginia earth and the burial task they must perform. In the forefront of the image, the viewer’s eye is drawn to the seated black man and the skeletal remains of American Civil War soldiers alongside him. He gazes back at the camera, his head tilted slightly to the left, close to the first of five skulls that look like macabre extensions of his own body. The five skulls anchor the five living figures in the image and provide a figurative line of defense against possible threat.

The Civil War was imagined as a white man’s war; visually devoid of black soldiers and their corporeal sacrifice, the imagery that remains is instead a visual register of white sacrifice. White soldiers dying for the sins of the country and the sins of black people — that is, the sin that is slavery. The photographic archive of the war is one of astounding substance and meaning, but also astounding absence and refusal. There, in the precise envisioning of the archive, we see few images of African Americans outside their prescribed roles of subservience; they are presented mostly as servants, refugees, contraband, gravediggers. We can imagine that the graves dug signify these men’s own buried or submerged citizenship that does not allow black Americans to firmly situate themselves within the geographic space of the nation. Instead, they are seen to be ever awaiting a future reconciliation that is never to arrive but is always on its way. Black Americans, as this image intimates, exist on the periphery of the national family, and documentary photographs illustrate this repeatedly.

Something of the memory of the American Civil War haunts the present, aided by these photographs. Beyond the 600,000 dead and the catastrophe of its ruined landscape, something else is present, palpable and visible. It is a hovering sense of national mourning that has not sustained African Americans within the national imaginary: “A scaffolding of bone we tread upon, forgetting,” as the poet Natasha Trethewey writes. A past and a future tense of racial hegemony. It begins in the photographic archive of dead Civil War soldiers, facilitating a process of mourning that reinforces citizenship and national belonging. Yet black soldiers exist outside of this framework.

Black Americans exist on the periphery of the national family, and documentary photographs illustrate this repeatedly.

A perusal of the Prints and Photographs Division at the Library of Congress shows the available archive has its limitations. Before a search for African American soldiers in the Civil War can begin, the researcher is informed that “images of African American soldiers are not well-represented” in the archive. Instead, “most photographs show African Americans as civilians attached to the military, and as ‘contraband’ and refugees.” These images convey a repeated metaphor of black subjectivity occupying an impossible duality of property and person, of contraband and comrade, and of refugee and citizen.

The paucity of images of African Americans in the photographic archive of the Civil War (composed of nearly 1 million images) replicates an erasure of visible blackness when that blackness is a part of the discourse of the event. In the aftermath of the Civil War and its ghostly remembrances, in the sliver of space between slavery’s demise and the spectacular production of lynching photography, the recovery mission of the nation doubled black death against a refusal of citizenship, necessitating the production of photographic memory on the part of African Americans to make space for the imagistic absence of black subjects and black subjectivity.

Of the famous Gardner photographs of deceased white Civil War soldiers blanketing battlefields across the country, Susan Sontag writes, “With our dead, there has always been a powerful interdiction against showing the naked face.” For Sontag, this is what gives the images their exceptional force, as “Union and Confederate soldiers lie on their backs, with the faces of some clearly visible.” It is a consolidation of racial alignment that allows this to be visualized and held in memory. White soldiers, even the traitorous Confederates, are seen as the epitome of sacrifice — to die for the preservation of an idea, white supremacy — while black soldiers register as the contraband white lives are sacrificed for.

Encased in a refusal to incorporate black people into the national imaginary, contemporary literature about the Civil War is more than just a reclaiming of the available archive: It is a reconfiguration of what it means to read against the grain of what is already there. I want to think about the photographic space opened by the onset of the Civil War as one that framed black subjectivity in increasingly narrowing parameters, even as a separate African American archive existed. I also want to think about the space of contemporary photography as expansive enough to imagine black futurity against the containing register of race and nation.

Decades after the Civil War ends, stereographs of black laborers culling cotton appeared in the United States. These images then, visually out of time, are also solidified through a photographic stasis that attempts to hold black Americans in a state of enslavement that seemingly never ends. The never-ending extension of slavery’s presence is the disciplinary framework of racialized violence we have come to know. How then to discuss the pleasures of looking when those doing the looking are white, while the wounded, exploited, and dead are black? Black writers, artists, and activists have not had the luxury of passive attention. Not when, as Toni Morrison writes, “photographs of dead black bodies surrounded by happy white onlookers” are a central feature of lynching images in the United States.

Black writers, artists, and activists have not had the luxury of passive attention.

Mortevivum is the term I have come up with to understand this particular photographic phenomenon: the hyperavailability of images in the media that traffic in tropes of impending black death. These tropes cohere around an ocular logic steeped in racial violence (and the nostalgia engendered therein), and they make any tragedy, any crisis, an opportunity for viewers to find pleasure in black peoples’ pain. The doubling mechanism of mortevivum is the schematic cartography of unbelonging that hinges on the absence of black bodies in the photographic archive of the American Civil War, and the hyperpresence of black bodies in images of the dead at the end of the 20th century. Whiteness constructs the documentary photographic space within its own binary logic, marking the photograph in and through the bodies that it contains. If whiteness is sempervivum (the live forever) of the American Civil War in this documentary logic, then blackness functions as a default mortevivum (the death living). In acknowledging the limited representation of black soldiers in Civil War photographs, we confront the enduring legacy of racial exclusion and the imagery that continues to bind blackness to death.

Kimberly Juanita Brown is the inaugural director of the Institute for Black Intellectual and Cultural Life at Dartmouth College where she is also an Associate Professor of English and creative writing. She is the author of “The Repeating Body: Slavery’s Visual Resonance in the Contemporary” (Duke University Press) and “Mortevivum,” from which this article is adapted.