Jerry Thompson: How Photography Works

Photography matters, writes Jerry Thompson, because of how it works — not only as an artistic medium but also as a way of knowing. It’s with this provocative observation that Thompson begins “Why Photography Matters,” his wide-ranging and lucid meditation on why photography is unique among the picture-making arts. He constructs an argument that moves with natural logic from Thomas Pynchon (and why we read him for his vision of contemporary reality, not his command of miscellaneous facts) to Jonathan Swift to Plato to Emily Dickinson (who wrote “Tell all the Truth but tell it slant”) to detailed readings of photographs by Eugène Atget, Garry Winogrand, Marcia Due, Walker Evans, and Robert Frank. Forcefully and persuasively, he argues for photography as a medium whose business is not constructing fantasies pleasing to the eye or imagination, but describing the world in the toughest and deepest way. We’re pleased to share an excerpt from “Why Photography Matters” below.

Let me begin with Reason One, how photography works.

The camera is not only a tool for generating images.

Studio artists today use cameras to generate the pictorial raw materials they need in order to create works expressive of their individual talents and personal visions. For a studio artist, the camera is a source of material. The artist provides the form, shaping what the camera supplies into what the viewer sees as a work of art. The content of the artwork — what it has to say to the viewer, the experiences (emotional and intellectual) it prompts the viewer toward — this content comes from the artist, as it does when the work of art is a painting (or other kind of imagined image). The viewer contemplates the artist’s vision. What the artist presents, as her work progresses, is a progressively deeper exploration of that vision.

The viewer who follows the work of an artist over time may come to know many facts about the world, but that viewer comes to know those facts incidentally, the way a reader of novels by, say, Thomas Pynchon comes to know about the trajectories of ballistic missiles or the progress of E. coli infections. What the serious viewer comes to know about, what he could not learn from a technical manual or guidebook, however, is something else: the vision — the intellectual and moral world — of the artist. We don’t read Pynchon to learn about physics and military history; if we read him seriously we read him to learn about his vision of contemporary reality. We read him to come into contact with what ever since Immanuel Kant’s formulation of 1791 has been called his genius: his original, and unique, understanding of how the world works. According to Kant, what genius produces illuminates Nature’s rules, rules the genius him/herself can embody in his/her work but not explain, rules some later intelligence may be able to analyze and make understandable to others.

We don’t read Pynchon to learn about physics and military history; if we read him seriously we read him to learn about his vision of contemporary reality.

A studio artist works like a novelist. He or she may pay a great deal of attention to the details of everyday visible reality, but what he or she adds to those observations is the something else, the shaping form supplied by his or her genius. The details figure in, but they are not the main point. Walker Evans wrote in an undated note to himself that anyone who goes to Botticelli to learn about the dress and manners of the 15th century is a pedant and a fool. Few scholars of the future who look at Jan Groover’s breakthrough still-life arrangements of kitchen utensils will spend much time considering the development of the colander in the 1970s. The main point is not a compilation of facts about the objects seen, but the genius of their combination into an original composition.

Groover (d. 2012) was, as also was the Evans (there were more than one) who wrote that epigram, not only a photographer but also an artist. But not all artists who use photography use it in the same way. To repeat: The camera is not only a tool for generating images.

To find a sharp contrast to what I have been calling a studio artist we need look no further than the first book of photographs ever published, William Henry Fox Talbot’s “The Pencil of Nature” (1844). This book consists of a number of the earliest photographs made, each pasted on a page with a brief essay/caption printed across from it. Here is an excerpt from one of the captions:

It frequently happens . . . —and this is one of the charms of photography—that the operator himself discovers on examination, perhaps long afterwards, that he has depicted many things he had no notion of at the time. Sometimes inscriptions and dates are found upon the buildings, or printed placards most irrelevant, are discovered upon their walls: sometimes a distant dial-plate is seen, and upon it — unconsciously recorded — the hour of the day at which the view was taken.

The implications of this pleasant observation extend to the extremes of recorded thought, both to its earliest beginnings and to the present now. For what Fox Talbot is describing is nothing less than a way of knowing the world that transcends our educations, our opinions, our intentions, hopes, and desires — in a word, our subjectivity. Talbot here acknowledges that the camera can show more than its operator understood he saw when he looked at the actual scene.

For a long time photographers who wanted to be artists viewed this rich harvest of detail as a large obstacle to be overcome rather than a “charm.” Many turn-of-the-century (19th to 20th) photographers turned to soft-focus lenses and worked on their negatives and prints by hand to obscure distracting detail. Others photographed carefully staged tableaux, and some pieced figures posed and photographed separately into a single composition. Now-little-known photographer-artists with names like Kuhn, Demachy, and Rejlander worked with laborious printing processes aimed at making their pictures look like real art — like prints and paintings. Alfred Stieglitz’s influential periodical “Camera Work” (1903–1917) ran an occasional column called “Lessons from the Old Masters.” The artist-photographers of this period disdained the humble documents produced by the portraitists and survey photographers. The goal of these artists was to produce prints to exhibit in salons, not pictures to be copied as engravings and printed in illustrated newspapers like Harper’s Weekly.

By 1920 a few photographers who thought of themselves as artists — notably Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Weston — had begun to reject this kind of art-making, embracing instead all the detail a sharp-focus lens could render. When in a 1923 note (written for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston) curator Ananda Coomaraswamy sought to describe the artistic accomplishment of Alfred Stieglitz, he stressed that Stieglitz the artist managed to enlist every tiny observation the sharp-focus lens of his large camera took in to support the “expression of his theme.” Stieglitz’s great achievement was that he could control every random texture and detail as completely as a conventional artist controlled those he created with his own hand.

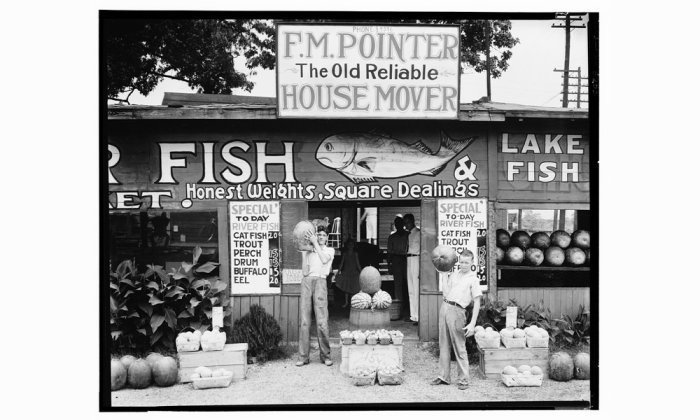

Talbot’s “rich harvest” had been tamed, enlisted to aid in the “expression of the theme.” But the wildness of the lens’s promiscuous harvest did not go away: It began to appeal to artists in love with “swift chance, disarray, wonder, and experiment.” Some of these artists had been to France and had heard of surrealism. One of them — Henri Cartier-Bresson (b. 1908) — was French, and had studied painting in Paris. For these enlightened ones, the chaotic intrusion of random details captured by an indiscriminate lens was not a problem to be controlled, but a gift to be embraced. By 1924, André Breton had appropriated a line from Isidore Ducasse (known as the Comte de Lautréamont) as a surrealist standard for beauty: the chance meeting of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table. Cartier-Bresson, his approximate contemporary Walker Evans (b. 1903), and other talented workers of their generation began to frame and snap violent contraries yoked together by force — the force of their vision — equaling and even exceeding Breton’s absurd suggestion.

If World War I could prod English poetry to change from Kipling to Eliot, its dislocations and the monstrous savagery of industrial warfare might also shake faith in the complete artistic control Coomaraswamy so admired in Stieglitz’s work. Evans, Cartier-Bresson, and others embraced “swift chance, disarray, wonder, and experiment.” For a brief moment, a door was left ajar — a door leading back to Fox Talbot’s “charm,” his welcome of the bracing surprises an image at least a little bit out of control might provide.

For a brief moment, a door was left ajar — a door leading back to Fox Talbot’s “charm,” his welcome of the bracing surprises an image at least a little bit out of control might provide.

The door was ajar only briefly. Another concern cut across that energetic acceptance of swift chance and wonder. That concern involved being an artist: Not even the greatest photographers have been immune to that siren’s song. More about this later.

Before we progress to Reason Two why photography matters now — because it provides a case study in contemporary understanding — let me wrap up Reason One: how photography works. Talbot, and the cohort including Evans and Cartier-Bresson seven decades later, proposed (however briefly) a new kind of epistemology, a new, hitherto impossible way of learning about the world. Since the Enlightenment, studying the world had meant proposing a model — mathema — and applying the model to the world of experience, what Kant’s translators called “the manifold of sensation.” The skills you had acquired, whether they were a humanist education or a skill in algebra or calculus (mathema gives us our word mathematics) — these skills were the light you shone upon raw reality, the world. You got answers to the questions you asked, and the answers you got to those questions were taken to be Truth.

Fox Talbot’s caption suggests the possibility of another approach (an approach, as we shall see, that was prefigured a long, long time earlier). Though he may not have been aware of or at all welcoming of the implication, his description of the indiscriminate power of the lens to record detail suggests the possibility that mathesis — reliance on the models we project to understand the world — may not have the final say or be the final measure of what is. Maybe — the quoted caption that presents his innocent understanding of one of the “charms” of photography suggests — maybe Fox Talbot’s brief essay/caption opens a door onto a new (though it in fact represents a re-calling, a re-remembering of a very old) way of understanding the world.

We are already into Reason Two, but let me spend one final, brief moment on Reason One: in a hurry, briskly, as our modern marching orders dictate. Fox Talbot and the modernists who preferred his acceptance of the disjunctive over the late-romantic pictorialist desire to enlist every element of the picture in service of “the expression of the theme” — the gentleman scientist and the urgent modernists both suggest a new way of understanding the world. It is an amalgam of educated understanding and chance discovery. It asks that its user be intellectually prepared, but also that he/she not let that preparation predict the findings. Swift chance, disarray, wonder, and experiment will also play a role. Mathesis — reliance on mathema — will cooperate with a willingness to accept pathema as well. The opposite of mathema (a model projected to enable understanding), pathema is an experience passively received: acquiescence to what is seen.

Our words sympathy and empathy stem from this root; pathetic evokes this root meaning (except when we use that word as casual jargon to mean something like woefully inadequate, or pitiful — a usage which encapsulates nicely our modern appraisal of the relative merits of aggression and reticence). When a pathema holds sway, the artist will no longer be Master of the Universe. He or she will be instead an attentive observer, a willing participant in, perhaps even a servant of, a system larger than that artist’s individual, personal, particular needs.

Jerry L. Thompson is a working photographer who also writes about photography. During the last three years of Walker Evans’s life he was Evans’s principal assistant and, for a time, printer of photographs. From 1973 until 1980 he was a member of the faculty of Yale University. Thompson is the author of “The Last Years of Walker Evans,” “Truth and Photography,” and “Why Photography Matters,” from which this article is excerpted.