Double Exposure: On the Public and Private Lives of Soviet Photo Collections

Eighty-one-year-old Konstantin Petrovich1 was excited to show us his photo archive and talk about his life. In anticipation of our visit in spring 2007, he had laid out multiple albums on the dining table of his one-room Moscow apartment, and so we suggested starting with the oldest photographs in his collection.

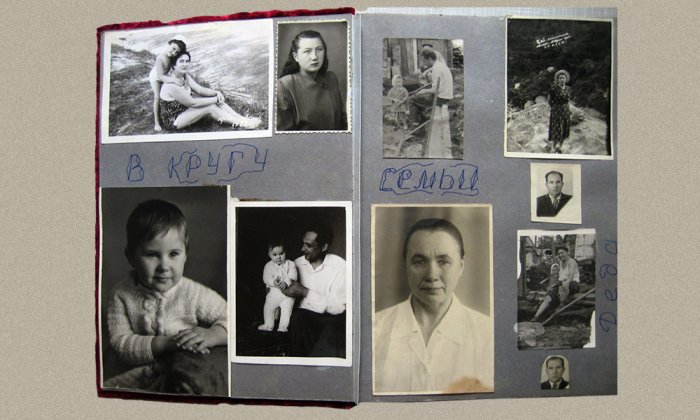

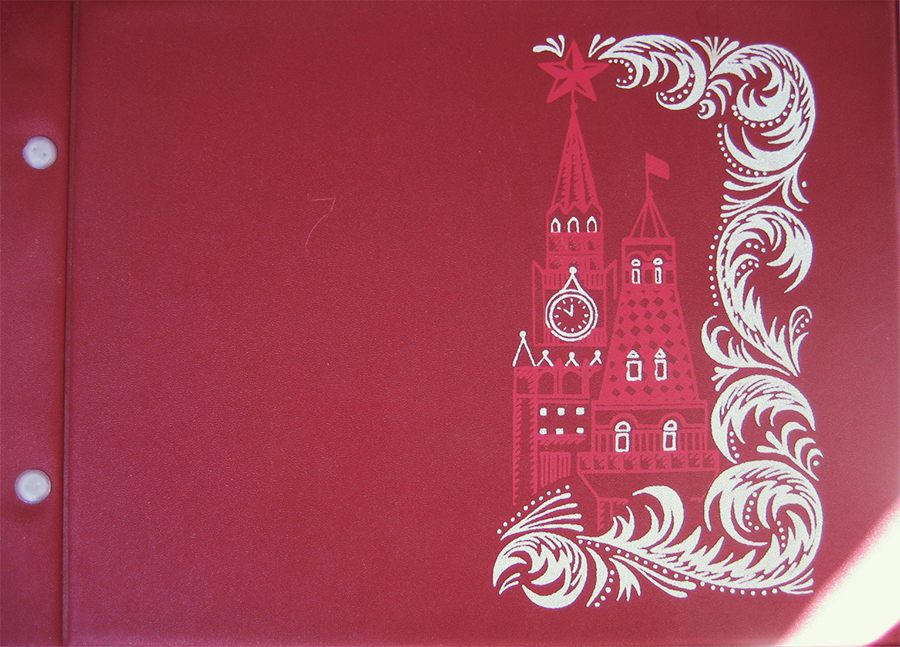

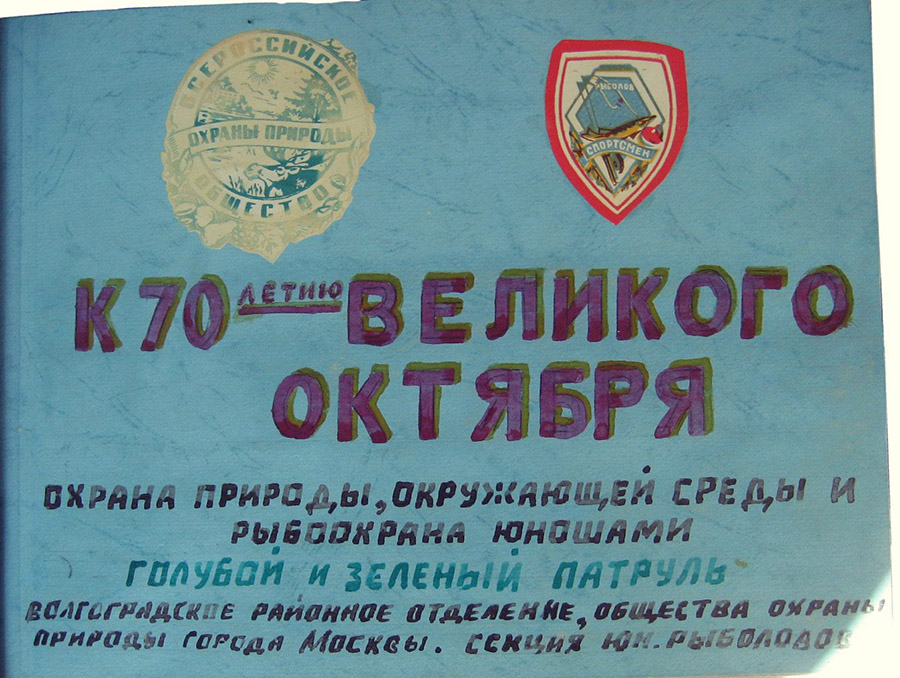

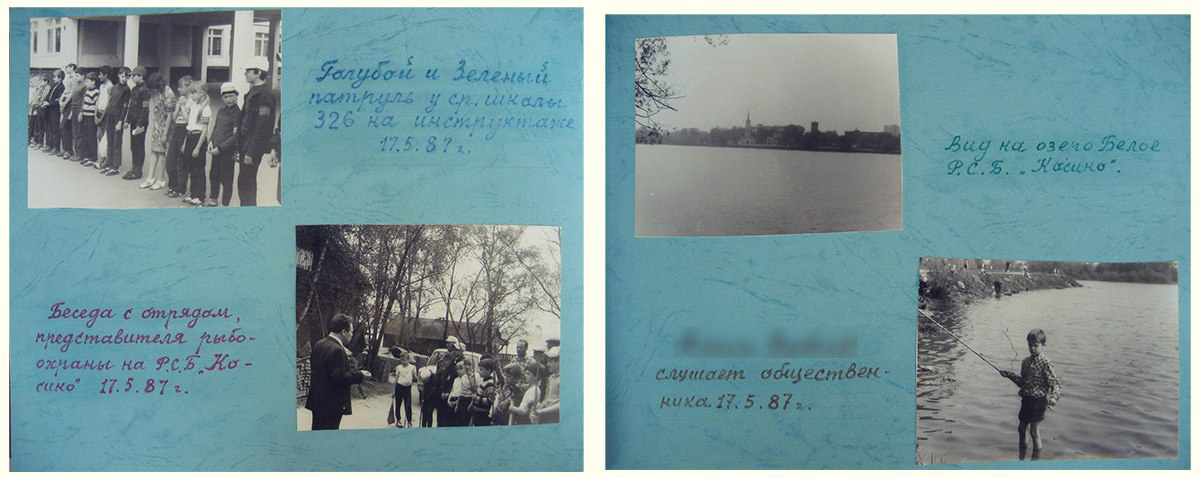

“Sure, let’s take the old times. You can document this one, this whole album.” We eagerly reached for it, encouraged by his warm welcome. Our enthusiasm was quickly replaced with puzzlement: this well-kept album, with its bright blue pages and red plastic cover decorated with an image of the Kremlin, was dedicated to the activities of a young fishermen’s unit of the Moscow society for environmental protection in the 1980s. Meticulously designed, signed, and dated, it opened with a handwritten dedication to the 70th anniversary of the “Great October [revolution]” and contained newspaper clippings, journal cutouts, and handwritten notes. But a family album it was not. Instead, it featured typed quotations from Russian writers of the 19th century, alongside quotes from Marx, Engels, and Lenin, interspersed with amateur photos of the album’s owner surrounded by members of the “blue and green youth patrol” in school and in nature. “Oh, so this is not really a family album. Looks like this is an album of your community work [obshchestvennaia rabota], right?,” we asked. “Well, this is not really a family one, but then again, it is [nu on vrode i ne semeinyi, a vrode i semeinyi],” our host replied without missing a beat.

The answer to what constitutes a “family album” seems intuitive, but the range of photographs we were shown by the families we visited were far from limited to the family circle.

This ambiguous answer underscores a set of expectations and assumptions about the nature of home-mode photography. The answer to what constitutes a “family album” seems intuitive, but the range of photographs we were shown by the families we visited were far from limited to the family circle, even in the most extended sense of the term; for the most part, they referenced multiple social contexts, and combined snapshots of family members with images of people who remained anonymous, even to the album’s owners. Emerging in the 19th century as a practice of “domesticating and organizing the world,” photographic albums trace a “continual process of becoming” — a visual representation of the self.2 Konstantin Petrovich’s choice to start with his “official” persona is a reminder that the self, as well as its vernacular visual representations via photography, implies a more complex entanglement of “private” and “public” than the writings on domestic photography typically anticipate.

Konstantin Petrovich’s attentively crafted album-cum-scrapbook, which was dedicated to his work with an association that trained schoolchildren in fishing and environmental protection, was a retirement project he attended to as both subject and creator. Shown in a position of authority, Konstantin Petrovich features in the album as a teacher and supervisor whose “communal” work was both an expression of political conformity and an emotionally rewarding endeavor. He is photographed giving lectures and awarding star pupils, attending group meetings and outdoor fishing trips. The photos aspire to reportage aesthetics, yet their quality is reminiscent of amateur tourist and family leisure snapshots.

The arrangement of the images in the album was punctuated by didactic quotes and slogans typed in all-caps as a reminder of the album’s edifying function: “SAVING NATURE IS THE TASK FOR THE ENTIRE NATION,” “GREEN AND BLUE PATROLS — NATURE’S YOUNG FRIENDS,” “KNOW HOW TO REST, LOVE AND PRESERVE NATURE!”3 These inscriptions enhanced the album’s genre ambiguity, even as our host downplayed them by saying, “You may read them or you may not [mozhno chitat’, a mozhno ne chitat’].” Filled with political quotations and stock landscape images, this multimedia object inscribed personal identity within the ideological framework of a “socially useful” Soviet pastime — blurring the line between hobby and work. It featured Konstantin Petrovich as an active pensioner and foregrounded Soviet forms of sociability: children lined up outside, attending award ceremonies, or sitting in a “presidium” of schoolchildren. When photographed as a group, the club members demonstrated the bodily discipline said to accompany the ongoing education of the mind, fixing their attention on the authority figure and modeling the spirit of collective cooperation. The captions referred to Konstantin Petrovich and select other club members in the third person, emphasizing that the album was made for outsiders’ eyes. Indeed, we learned that it was produced in three copies: “one for the school, one for the Society of Nature Protection, and one remains here.”4

The album’s composite nature and the multiple visual and verbal registers it tapped into were not unusual for Soviet family photo collections. While dedicated to community work, it was simultaneously presented as part and parcel of a personal biography and seen as an organic part of family life. In the peculiar palimpsest of Soviet sociability that is the Soviet-era photo collection, ideological and familial layers were inseparable, and the domestic was not limited to nuclear or even extended family circles.

The album’s role in Konstantin Petrovich’s biographical self-presentation acquired new significance when the conversation moved on to family history. When asked about other photographs kept in the family, he opened another album, which also sat prepared on the table. A contemporary of the first album, it had a similar plastic cover, was of the same size, and even contained the same blue pages that left the arrangement of the photos up to the discretion of the owner. This album contained images that were, for the most part, dated, but not signed. Their arrangement and provenance were markedly different from the “fishing club” album, with its profusion of ideological references, clearly defined temporal framework, and sole photographer. The implied viewer’s perspective shifted from “he” to “I”; clearly, this album was intended for home use only. Like the first album, it was also a retirement project in that it allowed Konstantin Petrovich to sort through and organize his photo collection; up to that moment, it had been stored in bags and boxes — a habit typical for many of the families we spoke to. Put together at approximately the same time, this album undertook a retrospective, multigenerational, and extended family mapping that avoided linear chronology when engaging with the past.

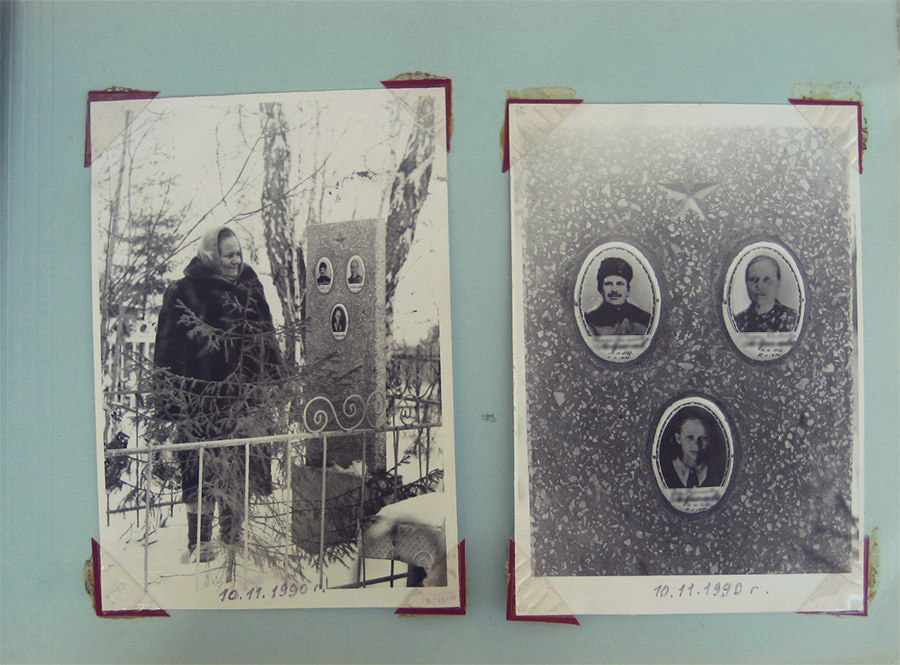

The second album opened with an image of a tombstone in the cemetery where his parents are buried, in his native Siberian village. The photos on the granite tombstone are oval-shaped, enamel-glazed portraits of his father, mother, and a sister who died young. In the first image, they are lovingly looked at by their other daughter, one of Konstantin Petrovich’s sisters — her gaze a reassurance of the living memory. Next to it is a close-up of the three funerary portraits on the tombstone, photographed on the same day. Side by side, the two snapshots reinforce the retrospective mode of album viewing and bring to the fore the complex relationship of photography with death.

Images of graves, funerals, and commemorative visits to the cemetery are not at all unusual in Russian photo collections.

Images of graves, funerals, and commemorative visits to the cemetery — albeit at odds with modern snapshot culture and the Kodak legacy of celebrating the bright and memorable moments of life — are not at all unusual in Russian photo collections. Images that “enable life and death to stand side by side before the camera” have been produced and circulated from the early years of photographic practice.5 And, as extensive photographic commemoration of the deceased was unfolding in American albums in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, amateur Russian photographers, including the writers Leonid Andreev and Maximilian Voloshinov, also explored the photographic medium’s uncanny relationship to death and doubling.6 In the Soviet times, funerary photography was perceived as an integral part of the ritual: These images were treasured and sent to family members who may not have been able to participate in the funeral, as a testament to the fact that the deceased received a “proper” burial and was publicly honored and mourned.7

Roland Barthes saw the relationship between photography and death as the very essence of the medium, its “photographic eidos” that makes time into a pervasive, piercing punctum, “the lacerating emphasis of the noeme (‘that-has-been’).”8 This introductory album page unwittingly gives visual form to Barthes’s observation. The page’s straightforward, almost didactic appearance is remarkably layered: The duplication of the photo within the photo, as well as the presence of the onlooker duplicating the gaze of the camera and the viewer, exemplifies the reflexive potential of the medium and exposes the act of doubling as the primary power of the camera’s gaze. Indeed, there are multiple processes of duplication at work here: The camera duplicates the loving gaze of the daughter, putting the viewer in her position; while the daughter herself models the filial veneration appropriate for, and likely in proxy of, Konstantin Petrovich’s own feelings for his parents.

Following this homage to his late parents, the second page of the album displayed their portrait, made in a photographic studio in the 1920s but bearing witness to prerevolutionary photographing conventions. It was placed side by side with a snapshot of Konstantin Petrovich’s wife, made almost four decades later, in 1961, as she sat on a park bench, holding a small bouquet of flowers in her hands. The photographed subjects look intensely at the photographer and, by extension, the viewers today, commanding our attention. The warm-colored sepia print of his family, seated in front of painted columns bracketing a barely discernable imaginary landscape, contrasts with the wintery cemetery scene, as well as the (relatively) recent image of his spouse. The temporal discrepancy and stylistic contrast are as instructive as they are casual, for family albums often bypass chronology for a different hierarchy of subjective importance. The album brings together singular images into a form of visual biography, and at the same time, exemplifies a single photograph’s capacity to stand in for the referent, irrespective of the particularities of its provenance.

The subsequent pages of the album unite Konstantin Petrovich’s Siberian family with his wife’s network of relatives. This “mapping” strategy was both deliberate and intuitively obvious to Konstantin Petrovich, who took the choice and sequence of the photographs to be natural and self-evident:

I am curious about these family photos. . . . How did they make it to these pages, who pasted them in, who selected them, and when did it happen?

Well [how they were] pasted, I got them [laughs] and glued them. So they got here. These are our relatives and here they follow [one after another].

The sequencing arrangement, starting with his parents’ tombstone and his married life, brought forth a complex family story. Konstantin Petrovich’s commentary on the album was structured by the tension that Marianne Hirsch, who studies intergenerational memory, described as the “contradiction between the myth of the ideal family and the lived reality of family life.”9 But while in Hirsch’s analysis the myth of the ideal family referred to the bourgeois ideal of patriarchal domesticity, the ideal Soviet family had different contours. The early Bolsheviks assumed that the social institute of the family would wither away together with other bourgeois practices. Yet with the Stalinist turn to conservative values, family was reenvisioned as the basic unit of social reproduction that was in many ways subservient to other socialist state institutions. This was where Soviet citizens were to restore their capacities for productive labor, but their energies were to be directed outside of the home: at work, school, and in active leisure and voluntary pursuits.10 A “proper” socialist family in the 1930s, when Konstantin Petrovich was growing up, was to be politically loyal, community-minded, and socially vigilant. That was exactly the family he had, until suddenly, he didn’t:

My father was a party member, and a revolutionary. He even had a gun. A real Bolshevik. He was the first leader of a collective farm in the Sargatskii district [in Siberia]. [He was] born in 1892, and in 1935 we buried him. He was tried on Article 58 as an “enemy of the people.”11 And he was sentenced to three years. [He was told], “We give you little, but you’ll remember it for a long time.” And two others got capital punishment. There was Breev, a Jew, and another one, a chief engineer, he was also Jewish. . . . [My father] got three years, but he was in prison only for a year. . . . Three times he went on a hunger strike. And then he contracted an open form of tuberculosis there. And because of that, he was released.12 They just brought him to the road . . . and some driver picked him up and took him home. . . . [After he died] we remained five children, with mother. The youngest was just one when he was arrested, and when he returned, she was already two. . . .

What memories do you have from those days?

Well, I remember that our people [nashi] came [to arrest], from our street, we knew them well. There was one militiaman and two witnesses: Semion Stepanovich and another comrade. . . . Then there was a court trial. We were there, but we did not understand anything. And our mother did not understand anything either. She was illiterate, she did not have any schooling. . . .

How did it affect you, the children?

Well, how could it have affected me? Just like it would affect anyone. Even now there are people arrested for political reasons. . . . But as a matter of fact, up to 1969, we were enemies of the people.

The label “enemy of the people” was extended to all of the children raised by Konstantin Petrovich’s mother, including her brother’s three children, whom she adopted after his death. In Konstantin Petrovich’s rendering, the overarching narrative, from arrest to rehabilitation, fused the story of the father and son into a tale of redemption. Indeed, the album compensated for his childhood stigma by highlighting Konstantin Petrovich’s biographical milestones: his successful career in the military, his well-to-do family, and regular visits to state-run health resorts.

Konstantin Petrovich’s photo collection made space both for his self-expression as a model Soviet community activist and for his more complex and long-silenced life story.

Returning to the initial contrast between the two albums, we can understand Konstantin Petrovich’s decision to start with the “public” album as a choice to display his socially rewarded biography before exposing the more sensitive parts of his family history. In its turn, the “private” album’s opening image at the cemetery, taken after the passing of his mother in 1970, and not long after the family’s official rehabilitation, not only embodied feelings of mourning and loss, but contained a reference to social acclaim — a five-point star engraving on the tombstone. Supporting the personal narrative, the monument, and by extension, the photograph, symbolically reclaimed the “Soviet hero” status and acted as material embodiments of the family’s full Soviet reintegration.

Konstantin Petrovich’s photo collection, in other words, made space both for his self-expression as a model Soviet community activist, and for his more complex and long-silenced life story: a young boy who witnessed his father’s unjust arrest and untimely death, and, in the course of his life, successfully overcame an imposed stigma. The contrast between these stories seems dramatic, and their copresence and entanglement are worthy of special attention. For any Soviet citizen with a biographic blemish (as most Soviet citizens of Konstantin Petrovich’s generation could be described, historian Sheila Fitzpatrick has argued), enthusiastic participation in productive collective endeavors was the only acceptable path to social inclusion.13 From this standpoint, the two albums that opened our conversation with Konstantin Petrovich were far from contradictory: The long shadow of suspicion cast on him and his family by his father’s arrest made the visual evidence of his social and community activism vitally important. This pressure makes Soviet-era domestic photo collections extraordinarily layered objects; they can testify to the biographical hardships that families lived through, as well as to the rituals of collective and social incorporation that involved, but also transcended the family circle — connecting them to the imagined community of “Soviet people” at large.

Oksana Sarkisova is Research Fellow at the Vera and Donald Blinken Open Society Archives and cofounder of the Visual Studies Platform at Central European University. She is the author of “Screening Soviet Nationalities” and coeditor of “Past for the Eyes.”

Olga Shevchenko is Paul H. Hunn ’55 Professor in Social Studies at the Department of Anthropology and Sociology at Williams College. She is the author of “Crisis and the Everyday in Postsocialist Moscow” and the editor of “Double Exposure: Memory and Photography.”

Sarkisova and Shevchenko are the authors of “In Visible Presence,” from which this article is excerpted.

- Konstantin Petrovich is a pseudonym that reflects the polite age-appropriate form of address in Russian: a first name followed by a patronymic. While committed to protecting research participants’ anonymity in our book, we acknowledge limitations of aiming for it in a book rich with personal photographs. To balance image poignancy and privacy, we use portraits sparingly, with explicit permission. Our ethical obligation is to preserve the stories and images entrusted to us.

- Elizabeth Siegel, “An Age of Albums,” in Photography: The Origins, 1839–1890, ed. Walter Guadagnini (Milan: Skira, 2010), 20; Geoffrey Batchen, Forget Me Not: Photography and Remembrance (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2004), 97.

- In Russian, the slogans are as follows: Okhrana prirody—vsenarodnoe delo; Zelenyi i goluboi patrul’—iunyi drug prirody; Umei otdyhat’, liubit’ i berech prirodu!

- Many Soviet organizations regularly produced such albums as visual accounts of their work. See Monica Rüthers, “Picturing Soviet Childhood: Photo Albums of Pioneer Camps,” Jahrbücher für Geschichte Osteuropas 67, no. 1 (2019): 65–95, on similarly formal pioneer camp albums produced in the 1970s. For a study using photographic albums of the Saratov orphanage to address forms of “institutional gaze” and its appropriation, see Pavel Romanov, “Landshafty pamiati: opyt prochtenia fotoal’bomov,” in Vizual’naia antropologia: Novye vzgliady na sotsial’nuyu real’nost’, ed. Elena Iarskaia-Smirnova et al. (Saratov: Nauchnaia kniga, 2007), 146–168, esp. 157–161.

- Batchen, Forget Me Not, 12. See also Jay Ruby, Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995).

- Katherine M. H. Reischl, Photographic Literacy: Cameras in the Hands of Russian Authors (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2018), 55–98. For a meditation on a non-European relationship between death and photography, see Jeehey Kim, “Korean Funerary Photo-Portraiture,” Photographies 2, no. 1 (2009): 7–20.

- For more on the conventions for a “proper” peasant burial, see Vadim Lurie and Oleg Nikolaev, “‘Pokhoronili khorosho’: O pokhoronnykh fotografiiakh v russkoi kul’ture,” 60 Parallel 4 (2011): 70–77.

- Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 14–15, 96, italics in the original.

- Marianne Hirsch, ed., The Familial Gaze (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College, 1999), 8.

- On the early Soviet approaches to the family, see Christina Kiaer and Eric Naiman, eds., Everyday Life in Early Soviet Russia: Taking the Revolution Inside (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2006). On the literary ideology of the family in the Stalin era, see Katerina Clark, The Soviet Novel: History as Ritual (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1981).

- The notorious Article 58 of the Soviet Penal Code was introduced in 1927 and remained in force until 1961. In 1934, additional paragraphs on “betrayal of the Motherland” were added. During Stalin’s rule, Article 58 was recurrently used to imprison or execute Soviet citizens, many of whom were rehabilitated posthumously “for lack of corpus delicti.” The sentence ranged from six months imprisonment, as a minimum, up to and including the death sentence.

- The Soviet Gulag system practiced early release of prisoners who were considered terminally ill as one way of controlling death statistics in the labor camps; see Galina Ivanova, Istoria GULAGa, 1918–1958: Sotsial’no-ekonomicheskii i politiko-pravovoi aspekty (Moscow: Nauka, 2006). For the first English-language in-depth study of this practice (aktirovka in Russian) see Mikhail Nakonechnyi, “‘Factory of Invalids’: Mortality, Disability and Early Release on Medical Grounds in GULAG, 1930–1955,” PhD thesis, University of Oxford (2020); and Mikhail Nakonechnyi, “‘They Won’t Survive for Long’: Soviet Officials on Medical Release Procedures,” in Rethinking the Gulag: Identities, Sources, Legacies, ed. Alan Barenberg and Emily D. Johnson (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2022).

- See Sheila Fitzpatrick, Tear Off the Masks! Identity and Imposture in Twentieth-Century Russia (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005). For a discussion of productive collective activity as a way of self-making in early Soviet Russia, see Serguei Alex Oushakine, “The Flexible and the Pliant: Disturbed Organisms of Soviet Modernity,” Cultural Anthropology 19, no. 3 (2004): 392–428.