‘Goodbye to my dreams of being an artist’: Santiago Ramón y Cajal’s Reflections on Art and Idealism

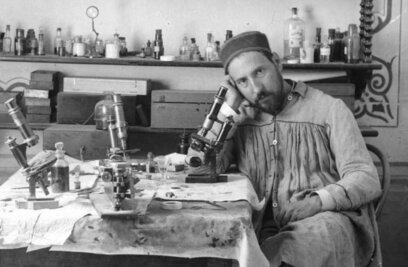

Starting from the most humble of beginnings, Santiago Ramón y Cajal was to become not only Spain’s most distinguished scientist but also, arguably, the founder of the discipline we now know as neuroscience. Much has been written about his scientific career, but one of the great charms of his autobiography, excerpted below, is how much attention is given to his nonscientific life.

Over 250 pages of the book are dedicated to his childhood and youth. In these pages he reflects on his love for the Spanish countryside and his frustration with the backwardness of its political and educational leaders, his affection for his family, his dreams and weaknesses, his fascination with birds and photography, among many other topics. In the excerpt that follows, Cajal recounts the unfolding of his artistic tendencies and the harsh dictum of a dream-killing housepainter, and ruminates on utilitarianism, idealism, and his childhood mischief.

About that time [early 1860s], if my memory does not deceive me, my artistic instincts began or at any rate showed a great increase. When I was about eight or nine years old, I suppose, I already had an irresistible mania for scribbling on paper, drawing ornaments in books, daubing on walls, gates, doors, and recently painted facades, all sorts of designs, warlike scenes, and incidents of the bull ring. A smooth white wall exercised upon me an irresistible fascination.

Whenever I got hold of a few cents I bought paper or pencils; but, as I could not draw at home because my parents considered painting a sinful amusement, I went out into the country, and sitting upon a bank at the side of the road, drew carts, horses, villagers, and whatever objects of the countryside interested me. Of all these I made a great collection, which I guarded like a treasure of gold. I took pleasure also in adorning my drawings with colors, which I obtained by scraping the paint from the walls or by soaking the bright red or dark blue bindings of the little books of cigarette paper, which at that time were painted with soluble colors. I remember that I attained great skill in extracting the dye from colored papers, which I employed also in place of brushes damped and rolled up in the shape of a stump; an occupation which was forced upon me by the lack of a box of paints and of money to buy them.

My artistic tastes, ever more definite and absorbing, led me to habits of solitude and contributed not a little to the shy character which so much distressed my parents. In reality, my habitual reclusiveness did not spring from aversion to social intercourse, since, as we have already seen, that of the boys contented and satisfied me; it sprang from the need of removing myself during my artistic efforts and my clandestine manufacture of instruments of music and of war from the severe vigilance of older people.

My father, who was more laborious and studious than most people, had grown up with a mental hiatus; he was almost completely lacking in artistic sense and he repudiated or despised all culture of a literary or of a purely ornamental or recreative nature. He had formed an extremely severe and rigid ideal of life. He was what educationists call a pure intellectualist. Man he regarded as a mere machine for knowledge and production, which had to be trained very early in order to be ready for the possible contingencies and reverses of life. This somewhat positivistic tendency I believe to have been not innate but acquired; it was an extreme adaptation brought about by the gloomy spiritual atmosphere which surrounded his youth. That incurable fear of poverty often represents the bitter lees left in the heart by the harsh struggle with misery, injustice, and neglect.

In the family circle this utilitarian and decidedly pessimistic outlook had two consequences — overwork and the most rigid economy. My poor mother, who was already very economical and a good manager by nature, made incredible sacrifices to obviate any superfluous expenditure and to conform with this system of exaggerated foresight. It was necessary to economize at all costs.

“In the theater of my feverish imagination, I substituted for the common beings who work and economize ideal people with no other occupation than the serene contemplation of youth and beauty.”

Far be it from me to censure a course of conduct which made it possible for my parents to amass the funds necessary for moving to Zaragoza, for providing a career for their sons, and for creating for themselves a position, if not brilliant and showy, at least comfortable and free from anxiety; but it must be recognized that the spirit of economy has commonsense limits which it is rather dangerous to exceed. Excessive saving declines rapidly into miserliness, falling into the absurdity of considering even necessaries superfluous; it banishes from the hearth the happiness which ordinarily springs from the satisfaction of a thousand innocent caprices and the possession of inexpensive trifles which would not be burdensome; it prevents the desirable relaxations of the novel, the theater, painting, and music, which are not vices but instinctive necessities for young people, for which every wise and well-regulated education must provide; and it loosens in the family the bonds of affection, for the children get the habit of regarding their parents as the perpetual preventers of present happiness. Nor may it be forgotten that every age has its pleasures as well as its troubles, and that it is a very harsh rule of conduct which sacrifices entirely those of youth for the sake of the distant and problematical enjoyments of maturity.

I trust that the reader will find it natural that I reacted obstinately against so gloomy an ideal of life, which killed in flower all my boyish illusions and cut off sharply the impulses of my budding fantasy. Certainly, without the mysterious attractiveness of for bidden fruit the wings of my imagination would have extended, but they would perhaps not have reached the hypertrophic development which they attained. Dissatisfied with the world around me, I took refuge within myself. In the theater of my feverish imagination, I substituted for the common beings who work and economize ideal people with no other occupation than the serene contemplation of youth and beauty. Translating my dreams on to paper, with my pencil as a magic wand, I constructed a world according to my own fancy, containing all those things which nourished my dreams. Dantesque countrysides, pleasant and smiling valleys, devastating wars, Greek and Roman heroes, the great events of history all flowed from my restless pencil, which paid little attention to common scenes, to ordinary nature, or to the activities of everyday life. My specialty was the terrible incidents of war; and so in a moment I covered a wall with sinking ships, with sailors rescued on planks, with ancient heroes covered with shining harness and protected by plumed helmets, with catapults, battlements, moats, horses, and riders.

It is unnecessary to say that, being drawn from memory, these scenes did not pass beyond the category of pretentious and grotesque scrawls or lifeless mannikins. I very seldom drew modern soldiers: I found them insignificant, prosaic, laden with a knapsack and a blanket which gives them the air of porters, with their ugly shakos, a poor parody of the knightly and majestic casque, and with their short and almost inoffensive bayonets, a sort of spit without a handle, a ridiculous caricature of the elegant and efficient sword. Besides, modern war, with firearms, I considered inartistic and cowardly. I believed that in it the most gallant, intrepid, and bold warrior could no longer win, but rather the most fainthearted and mean, who fired his gun from a protected spot, and without risk. I regarded such a manner of fighting as more liable to degrade the human race than to improve it: truly a selection of the least fit.

Doubtless old-time wars were death dealing, but they had the prestige of elegance of gesture and of apparel. In accordance with the principle of evolution, the laurel almost always crowned in them the supreme artists of energy, form, and rhythm. Today the enemies’ bullet decimates in preference the big, the brave, and the bold, and respects the small, the weak, and the fainthearted. Henceforth, I said to myself, not the Greeks but the Persians will triumph; unarmed heroism will be overcome by wealth and cold calculation; the fox will disarm the lion; and those imposing athletes with strong arms hardened in a thousand glorious combats, who, like Milo of Crotona, were the shield and bulwark of their country and the light and glory of the human race, will remain relegated to the sad and base condition of the strong man in a side show. Obviously, in my ignorance, I was not capable of formulating these thoughts, but they represent my state of mind during that period.

From warlike interests I turned to the lives of the saints. But when I painted saints I preferred the active to the contemplative ones; I adored those who were fighters, among whom, as the reader will easily guess, my own saint, that is to say Santiago (St. James) the apostle, the patron of Spain and the terror of the Moor, enjoyed all my sympathies. I delighted in representing him as I had seen him in prints, or else galloping intrepidly over a large surface thickly covered with Moorish corpses, his bloodstained sword in his right hand and his shield in his left. With what pious care I colored the helmet with a little gamboge and passed a band of blue along the sword, and lingered over the black beards, which I made long and wavy as I supposed that those of the Apostles must be!

One of the copies of the Apostle St. James drawn on paper and illuminated with certain colors which I was able to “snitch” from the church, was the cause of a serious grief and of my father, who was already averse to all kinds of aesthetic tendencies, becoming the declared enemy of my artistic inclinations. Wearied, no doubt, of depriving me of pencils and drawings and seeing the ardent vocation to wards painting which I exhibited, he decided to determine whether those scrawls had any merit and promised for their author the glories of a Velazquez or the failures of an Orbaneja.

As there was no one in the town sufficiently qualified as a critic of drawing, the author of my days turned to a certain plasterer and decorator from somewhere else, who arrived about that time in Ayerbe, where the chapter had engaged him to whitewash and paint the walls of the church, damaged and scorched by a recent fire. When I arrived in the presence of the Aristarch, I timidly displayed my picture, which was incorrect enough; the house painter looked at it and looked at it again; and after moving his head significantly and adopting a solemn and judicial attitude he exclaimed, “What a daub! Neither is this an Apostle, nor has the figure proportions, nor are the draperies right-nor will the child ever be an artist.” I remained stricken dumb by the categorical verdict. And to think that those crude sketches could pass today for one of the quite tolerable manifestations of modern painting! But then, classicism reigned and was indeed a truly fanatical cult. My father dared to reply, “But does the boy really show no aptitude for art.” “None, my friend,” replied the wall scraper inexorably, and turning to me, he added, “Come here, Mr. Painter of mannikins, and look at the large hands of your apostle. They are like a glove maker’s samples! Look at the shortness of the body, where the eight heads’ length prescribed by the canons have diminished to a bare seven, and, finally, look at the horse, which appears to have been taken from a merry-go-round!”

Choked with disappointment, I proffered some timid excuses; but the cultivator of red ochre and white lead spoke ex cathedra and gave me up with finality. The significant silence of my father told me clearly that all was lost. In fact, the opinion of the dauber of walls was received in my family like the pronouncement of an Academy of Fine Arts. It was decided, therefore, that I should renounce my madness over drawing and prepare myself to follow a medical career.

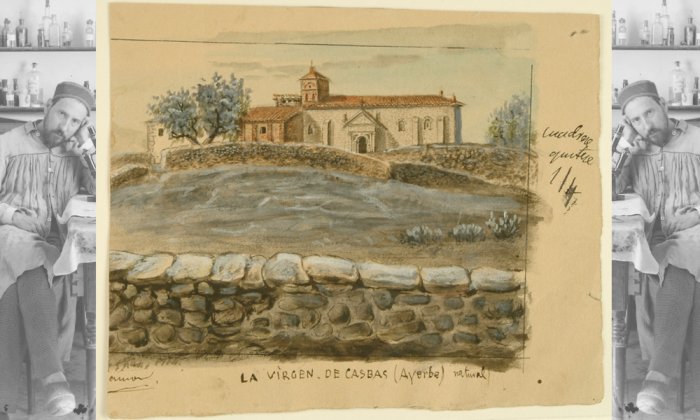

The persecution of my poor pencils, charcoals, and papers was consequently redoubled, and I had to employ all the arts of dissimulation to hide them and to conceal myself when, swept away by my favorite passion, I amused myself with sketching bulls, horses, soldiers, and landscapes. I still preserve some of those childish efforts so much disliked by the famous plasterer. As a sample of my drawings of that period, I reproduce an aquarelle in which serious defects in proportion are immediately evident. It is a somewhat grotesque representation of an Aragonese working-man in a tavern, grasping the classic porron [a wine bottle with a long side spout from which the wine is poured into the mouth.] But who draws well at nine years of age without guidance or methodical studies?

Thus there began between my parents and me a silent war of duty against desire. Thus there arose in my father the most obstinate opposition to a vocation which was so clearly indicated; an opposition which was to continue for 10 or 12 years and as a result of which, if all my artistic tendencies were not entirely wrecked, at least all my aspirations died out for good.

“Farewell to ambitious dreams of glory, illusions of future greatness! I must exchange the magic palette of the painter for the nasty and prosaic bag of surgical instruments!”

Farewell to ambitious dreams of glory, illusions of future greatness! I must exchange the magic palette of the painter for the nasty and prosaic bag of surgical instruments! The enchanted brush, the creator of life, must be given up for the cruel scalpel, which wards off death; the maulstick of the painter, like the scepter of a king, for the knotted walking-stick of a village doctor!

My studies meanwhile progressed poorly. I went to school, but paid little attention and did not learn much. My elementary knowledge was really good enough, thanks to the lessons of my father, who now sent me to the municipal school with the idea more of subduing than of enlightening me. This prudent bridle upon my liberty was made advisable by my waywardness and my tendency to play truant. My father would have liked to keep watch over me and to chastise me upon the first transgression, but was prevented by his extensive practice in the town and especially by his frequent visits to the adjacent villages of Linás, Riglos, Los Anguiles, and Fontellas. The oversight of my actions and the punishment of my trespasses was therefore placed in the hands of the schoolmaster and of my mother, who, being already sufficiently occupied with the care of the younger children and the management of the household, could not devote to her first born all the attention desired.

In spite of the precaution taken, the devil often tempted me. Whenever an opportunity presented itself, we mischief-makers of the school took full advantage of it, celebrating it sometimes with battles staged in the suburbs; at others with exploring and climbing the ruins of the historic castle, where we delighted in reproducing the struggles of olden days and sometimes plunging into the neighboring sarda, an ancient wood of live-oaks, where we spent long hours shooting arrows at the birds and hunting for magpies’ nests.

It was in this last occupation that I once suffered a painful accident. I had climbed up into a live-oak and undertaken the examination of a magpie’s nest when I touched something soft and furry, and quickly withdrew my hand covered with blood and bitten painfully. A family of rats, which had taken possession of the nest and devoured the eggs, had turned furiously against the intruder who came to disturb them in the peaceful possession of their stolen home.

On another occasion my craze for nests placed me in a very dangerous situation. I was anxious to examine an eagle’s nest, so climbed with difficulty down a series of ledges on a tremendous cliff in the Sierra de Linás and looked from close at hand at the still naked eaglets, which stared at me with terror. I could not actually reach them, however. Fearing attack by the eagles, of which I thought that I could hear the screeches, I tried to escape from the projecting ledge where I was perched, but upon attempting the ascent I met with insurmountable difficulties. The shelf to which I had got down by a foolhardy jump projected from a lofty and almost smooth wall. There I remained for hours, caught as in a trap, consumed by terrible anxiety, with a burning sun overhead, and in danger of death from hunger and thirst, as there was no one to help me in these solitudes. Industrious use of the clasp-knife which I always carried saved me at last. Thanks to this implement and to the relative softness of the rock, I was able to enlarge some narrow cracks until they provided sufficient hold for my hands and feet and thus set me at liberty. How many such rash actions I could relate did I not fear to abuse the reader’s patience!

Upon his return from the outlying villages, my father would inquire into the misdeeds and excesses of his sons and, rising in anger, would favor us with a formidable thrashing, besides reproaching my poor mother (a thing which distressed us greatly) for what he called her carelessness and excessive softness towards us.

The announcement of these paternal floggings, which, by a logical progression and in suitable adaptation to the hardening of our skins, began with a whip and ended with cudgels and tongs, inspired us with absolute terror; and so it happened upon one occasion that, to avoid this rather vigorous paternal caress, we ran away from home, thereby causing deep grief to our mother, who sought us anxiously throughout the town.

I remember that my brother and I, having played truant one afternoon and knowing that someone had told our severe progenitor, resolved to escape to the hills, where we remained for several days, pillaging the fields and living on fruits and roots, until one night, when we were already beginning to enjoy the wild life, our father, who was looking for us in every hiding place in the neighboring woods, discovered us sleeping peacefully in a lime kiln. He shook us violently, bound us arm to arm, and led us in that shameful attitude back to the town, where we had to endure the jeers of the women and children in the streets.

As the reader will have gathered, beatings and thrashings were the usual conclusion of our escapades, but, as a result of the process of adaptation already mentioned, the rods made us smart but did not correct us. While the bruises were fresh, we refrained successfully from backsliding, but once they had vanished we forgot our intentions of reformation. In fact, natural impulses, when they are very strong, may be modified somewhat, and often conceal themselves, but are never obliterated. Thwarted in our natural tastes, deprived of the pleasure of camping among the crags and ravines, there to exercise the artist’s pencil, the warrior’s arrow, or the naturalist’s net, we sullenly attended school, without being corrected or made reliable. All that was accomplished was to change the scene of our misdeeds: The sketches of the countryside were replaced by caricatures of the master; the battles in the open air were changed to skirmishes among the benches, in which paper pellets, cabbage-stalks, haws, chick peas, and kidney beans served as projectiles; and, in default of paper for drawings, I made use of the wide margins of the catechism, which were filled with tasteless ornamentations, conceits, and puppets, some having reference to the pious text, others rather irreverent and profane.

In school, my caricatures, which passed from hand to hand, and my unsuppressible chatter with my fellows exasperated the master so much that more than once he had recourse, in the effort to daunt me, to locking me up in the classical dark chamber — a room almost underground, overrun with mice, of which the youngsters felt a superstitious terror, but which I regarded as an opportunity for recreation, since it provided me with the calm and concentration necessary for planning my escapades of the next day.

There, in the darkness of the school prison, with no other light than that which filtered faintly through the cracks of the rickety window shutter, it fell to my lot to make a tremendous discovery in physics, which, in my utter ignorance, I supposed entirely new. I refer to the camera obscura, wrongly ascribed to Porta, though its real discoverer was Leonardo da Vinci.

The curious fact which I observed was as follows: The little shuttered window of my prison faced the square, which was bathed in sunlight and full of people. Having nothing to do, I happened to look at the ceiling and noticed with surprise that a slender beam of light projected upon it, head downwards and in natural colors, the people and the beasts of burden which passed outside. I widened the hole and found that the figures became vague and nebulous, I reduced the size of the opening with paper moistened in saliva, and observed with satisfaction that, corresponding with the reduction, the clearness and detail of the figures increased. Thence I concluded that the rays of light, as a result of their absolute straightness, paint an image of their source, whenever they are made to pass through a small hole. Naturally my theory lacked precision, ignorant as I was of the rudiments of optics. In any case, that simple and well-known experiment gave me a most exalted idea of physics, which I at once came to regard as the science of marvels. Of course I did not forget the wonders of the railway, of photography (recently invented at that time), of balloon ascents, etc. And my enthusiasm did not deceive me, for to physics we owe the glories of European civilization. If the laws and applications of that science could be extracted from the heritage of human knowledge, the race would step back at one stride to the condition of the cave men.

For the time being, very far from appreciating the magnificent perspectives which the study of natural forces opens to the spirit, I proposed to profit by my unexpected discovery; and, mounted upon a chair, I amused myself by tracing on paper the bright and living images which appeared to console me, like a caress, in the solitude of my prison. “What does the loss of liberty matter to me?” I thought. “I am prevented from rambling about the square, but in compensation the square comes to visit me. All these luminous shades are a faithful reproduction of reality and better than it is, since they are harmless.” From my cell I watched the games of the children, followed their quarrels, observed their gestures, and, in fact, enjoyed their play as if I were taking part in it.

“I am prevented from rambling about the square, but in compensation the square comes to visit me. All these luminous shades are a faithful reproduction of reality and better than it is, since they are harmless.”

Proud of my discovery, I became daily more attached to the realm of shadows. But I was so simple as to tell my comrades in confinement of my discovery, and they, laughing at my foolishness, assured me that the phenomenon was of no importance, since it was a natural thing and, as it were, a trick which the light plays when it enters dark rooms. How many interesting facts fail to be converted into fertile discoveries because their first observers regard them as natural and ordinary things, unworthy of thought and analysis. Oh that unlucky mental inertia, the lack of wonder of the ignorant! How it has delayed our acquaintance with the universe!

It is strange to see how the populace, which nourishes its imagination with tales of witches or saints, mysterious events and extraordinary occurrences, disdains the world around it as commonplace, monotonous and prosaic, without suspecting that at bottom it is all secret, mystery, and marvel.

For the rest, I have already said that my brilliant physical discovery could not gain me the honor of priority. Centuries earlier it had been made by the great Leonardo, who was not only a distinguished painter but also an illustrious physicist; and it may be presumed that in more distant times many others had observed the surprising phenomenon, though they published no account of it.

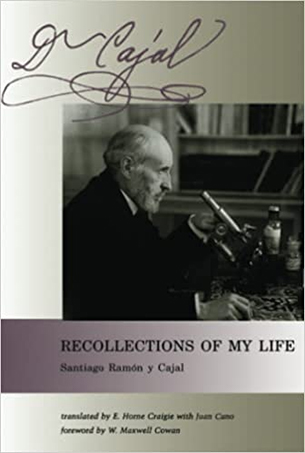

Santiago Ramón y Cajal (1852–1934) was a neuroscientist and pathologist, and Spain’s first Nobel laureate. This article is excerpted from his book “Recollections of My Life.”