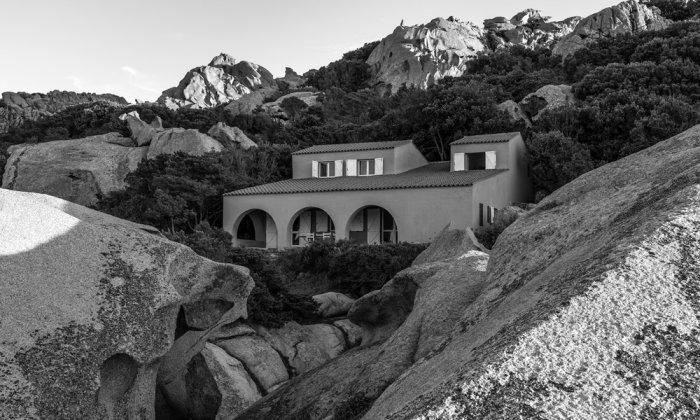

A Sentimental Autobiography of a Holiday Home Built in the North of Sardinia in the 1960s

How does a house shape experience? How does architecture establish a practice of living? Architect Sebastiano Brandolini’s book “The House at Capo d’Orso” invites readers on a meditative tour of his family’s house on the Sardinian coast, describing everything from the geology of the rocks beneath, to the history of the surrounding villages, to the way the shifting light measures the day. More than the story of a single summer home written by an accomplished architect, his book is a study of how place, the built environment, and daily practice make up our lives, at the most minute level of detail. Recalling the essays of Walter Benjamin, Bill Bryson, Rebecca Solnit, and Lawrence Weschler, Brandolini’s writing weaves literature, art history, and the transformation of Sardinia since the 1960s into a single fabric. The following text is excerpted from the prelude to the book.

Every house is a tangled web of things and incidents, a strange conjuncture that often seems to turn into a conspiracy. It is three things at once: the autobiography of whoever has built and used it, a portrait of the place it occupies, and the chance product of a range of temporal factors that may not germinate for years after they are encountered. Each house is associated with people, with geography, and with history.

“The House at Capo d’Orso” is a book of architecture that describes the web that time has woven around a particular vacation home, and one whose eccentricities continue to evolve and reveal new facets. The house is not my own work, but that of my parents; to them must go the credit for having conceived and created it. I inherited the place and today I am just the beneficiary and caretaker. My name may appear in the land register, but sentimentally it belongs to all those who, having spent time there, have enjoyed, understood, and even loved it, experiences which are possible only in this order. The house is located at Porto Ulisse, near Capo d’Orso, in the municipality of Palau, in the region of Gallura, on the island of Sardinia, in Italy, in the Mediterranean. It carries no postal address. A lot of people have slept or eaten there, but only a few have absorbed its essence.

It carries no postal address. A lot of people have slept or eaten there, but only a few have absorbed its essence.

Usually, those who do seem to understand the essence of the house begin to behave a little strangely, as if they were under its spell. They start to lose the power of speech, their movements slow down, they no longer respect the habits of fixed times, they avoid eating certain things, their gaze is frequently caught and held for long periods of time, their senses of hearing and smell are sharpened, they have absurd reactions, and present unexpected points of view, ideas that are revolutionary and anarchic. They raise fundamental questions about their lives, and in assigning less importance to practical matters lay themselves open to mystical notions or considerations of a religious order. These are just some of the possible side effects of the architecture and the place, which can vary widely.

When someone dies or goes away, houses are among the first things to change, and often to melt away and vanish. The furniture and other objects are discarded or divided among the heirs or put up for auction, or they change their position and their significance; papers that were thought to still be there disappear and have to be searched for; things which were thought to have been lost forever turn up unexpectedly, and in the end, in one way or another, everything is different. A new taste and a new approach to living arrive with the new owners or inhabitants; furniture stores change with every generation, and people’s homes take on a wholly different flavor. Newcomers usually make small but significant modifications, and thereby leave their individual marks; houses often turn into pastiches, and it is rare for the atmosphere and lifestyle of places as they were when they were born to be preserved. Even though the thorough iconographic and factual research carried out for historical movies and TV series helps us to understand and imagine what the houses of Pompeii, Venetian palazzi, Victorian country houses, or the Forbidden City in Beijing were once like, we are left with the impression that as generations succeed one another the original atmosphere of the architecture is always lost, and hardly ever replaced by something equally coherent and poetic. Perhaps atmosphere, so ephemeral and ethereal, is the true substance of architecture.

This sense of the effective impossibility of really preserving the spirit of a house was something I felt strongly in Nuoro, the city at the heart of Sardinia, when I visited the house-museum of Grazia Deledda (1871–1936), winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1926. The house dates from the second half of the 19th century and is located in Santu Pedru, a district inhabited by shepherds in the oldest part of the city. It is an example of a well-to-do Nuorese residence, on three stories, and with several inner courtyards on the ground floor: solid, well organized, and harmoniously proportioned. Deledda lived there until her marriage in 1900, when she moved to Rome. In 1913 the house was sold, but not subjected to alterations; later it was declared a national monument and in 1968 it was purchased by the municipality of Nuoro, which in 1979 handed it over to the Isre (Istituto Superiore Regionale Etnografico) for the symbolic price of 1,000 lire.

Over the years the institute, gradually coming into possession of manuscripts, photographs, documents, furniture, and personal items belonging to the writer, turned it into a house-museum, complete with many of the things that go into making a home. The kitchen is equipped with pans and baking molds; the room once used for carding and weaving wool has been put in order; the papers and books in the study are carefully arranged; the implements used for sheep-farming in the shady walled garden look ready for use. It is even explained to the visitor how the house was heated a hundred years ago (with an ingenious system of basins filled with burning coals), given that Nuoro is in the mountains and very cold in the winter. But as in all house-museums, and notwithstanding the faithful and painstaking historical reconstruction, what is missing here is the essence of what we might call the atmosphere of the great writer’s private world, at once evanescent and substantial. Was the house really like that? You come away with the impression that this is an excellent replica, but still a replica. The furniture and the knickknacks are there, but the spirit, the people, the sounds, the smells are lacking. Nothing is out of place; the pots and baskets have been emptied, literally and metaphorically. And so we realize just how difficult it is, however hard we try, to replicate the web of things and incidents that renders every house unique. Perhaps the best way to describe a place as it really was is in writing. Grazia Deledda’s last but unfinished work, “Cosima,” is an autobiography in which the descriptions of the family home in Santu Pedru are concrete and atmospheric, more faithful than its material reconstruction. Cosima is a book of architecture, even though there are no images. Indeed, perhaps for this very reason, I cannot help but quote a passage from this book.

The house was simple, but comfortable: two large rooms on each floor, with low ceilings, wooden floors and whitewashed walls; the entrance was divided in two by a partition: on the right the stairs, the first flight of granite, the rest of slate; on the left a few steps leading down to the cellar. … The room to the left of the entrance furnished with a high hard bed, a desk, a wide walnut wardrobe, and straw-bottomed, rustic-looking chairs gaily painted a light blue, was adapted to many uses; the room on the right was the dining room with a chestnut table, chairs like those others, and a fireplace with a beaten earth floor. Nothing else. Another entrance with a solid door also locked by hooks and chains led to the kitchen. And the kitchen was, as in all houses still patriarchal, the room most lived in, most warm with life and intimacy. … All in all, everything was simple and old in the ample kitchen well illuminated by a window that looked out onto the kitchen garden, and by a glass pane in the door leading to the courtyard. In the corner near the window, rose the massive oven with its smoke pipe in the wall and three burners along the edge; in a brazier next to these there was kept, night and day lit and covered with ashes, a bit of coke, and under the stone sink beneath the window, there was a bit of coal in a small cork bucket. But most often the meals were cooked over the flames of the fireplace or of the hearth, on thick tripods that could have served as seats. All the household furnishings in the kitchen were big and solid: the carefully plated bronze frying pans, the low chairs around the fireplace, the stools, the shelves for the crockery, the marble mortar to crush the salt, the table and the sideboard on which besides the pots was a wooden receptacle full of grated cheese, and for the servants a basket full of barley bread and something to munch with it.

According to this lengthy description a house can be summed up in the objects it contains, and these give a meaning to the way in which we live. Certain household articles reify our experiences and end up as self-portraits; others, originally practical objects, come to play an emotional role as well. The Museo del Costume in Nuoro displays Sardinian artifacts that are both decorative and useful, making us realize just how difficult it is to separate the two aspects. Jasper Morrison has published a whole book on the everyday objects of Portugal. Grazia Deledda, in her clean and objective style, describes the geography of the items in her house so well that she is able to make their utility tally with the empathy she felt toward them as a girl.

There are times when I am surprised by just how little trouble the history of architecture has taken to describe and re-create the atmosphere and light that once emanated and still emanates today from the places, buildings, facades, houses, rooms, materials, and finishes of the past. Even today’s architectural criticism takes little account of the atmosphere of places and glosses over this aspect, perhaps because it is considered too subjective, even too intimate, for it to be tackled with due objectivity. The history of architecture prefers to devote itself to describing in great detail the more concrete and perhaps more banal aspects of buildings, such as their form, organization, structure, language, and style. The widespread reification of domestic architecture today constitutes a problem, one that is far from secondary and, paradoxically, fostered by the interior design magazines, which perpetuate the idea of the discipline as a separate branch of architecture rather than an essential component of its identity.

Sardinia has a history, even if all too many have described it and continue to think of it as an empty island without one.

One of the themes of my book is tourism, and its role in the formation of new urban settlements, new landscapes, and a new collective imagination. In my view the architecture of tourism comprises all vacation homes, hotels, and activities ancillary to the fundamental economy, be they in the city, at the seaside, in the mountains, or in the countryside. Villages, towns, and cities where the majority of the accommodation is connected with tourism should be regarded as resorts. In short, tourism has become the raison d’être of many places. From this perspective, my house, and Palau, are in every respect part of the phenomenon of tourism.

In Sardinia, I am a tourist who observes the situation from the outside and is concerned principally with what pertains to him; here I am a visitor and have never become a resident. The people of Palau see the tourist resorts as something that does not concern them personally and for which they have only indirect responsibility. The tourists’ Palau is 10 times bigger than the residents’ Palau. So I wonder whether the architecture of tourism ought to be considered postcolonial. Perhaps, I tell myself, it is the expression of a weak and mild colonialism, one that is in any case founded on difference and distance with respect to the identity and mentality of the place. I ask myself this question every time I go to Sardinia. What is it for me, that image I have seen again and again over the course of my life, hundreds of times, arriving and leaving, that succession of gray mountain crests on the horizon of which I know neither the height, nor the substance, nor even how far away they are? What is my house to the guides who drive their boats noisily in front as they take tourists on trips around the archipelago? Just how great is the distance that still today separates me from this island? The architecture of tourism has never been assimilated by Sardinia, and the architecture of Sardinia has never really opened its doors to tourism.

Sardinia has a history, even if all too many have described it and continue to think of it as an empty island without one. There are few records of Sardinia’s distant past, and in this respect there is not much of which we can be certain, but this is in no way true of the island’s recent history. The last century has seen the arrival of industries, water reservoirs, ports, tourism, international transport, gastronomy, motorways, new landscapes … The last century of Sardinian history has seen disappearances and appearances at the social, economic, and geographic level. It is following in the tracks of the writers Grazia Deledda, Gavino Ledda, and Salvatore Satta that this story must be told.

Sebastiano Brandolini is an architect based in Milan, a professor at the Milan Polytechnic, and the author of architectural monographs and guidebooks. This article is excerpted from his book “The House at Capo d’Orso.”