Nagisa Oshima: Banishing Green

Nagisa Oshima (1932-2013) is generally regarded as the most important Japanese film director after Kurosawa and was one of Japan’s most productive and celebrated postwar artists. His early films represent the Japanese New Wave at its zenith, and the films he made in the years that followed won international acclaim.

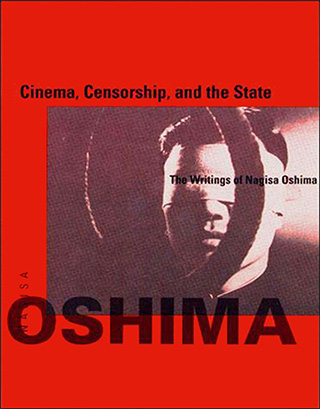

The more than 40 writings that make up his autobiography “Cinema, Censorship, and the State: The Writings of Nagisa Oshima, 1956–1978,” from which the following essay is excerpted, reveal a rare conjunction of personal candor and political commitment. Entertaining, concise, and disarmingly insightful, they trace in vivid and carefully articulated detail the development of Oshima’s theory and practice and recount the pivotal moments in his early life that shaped his vision. In the essay that follows, Oshima reflects on his deliberate exclusion of the color green in his first color film, “Cruel Story of Youth,” — to him, the color symbolized conformity and complacency within Japanese society — and grapples with the tension between capturing real scenes and transforming them into fantastical expressions.

The first time I made a film in color — my first film was in black and white and my second was in color — I imposed a small taboo on myself.

It was to never shoot the color green. It’s easy to avoid green costumes. There probably isn’t a lot of green furniture. You need only remove any green signs. The problem is the green of trees and plants. That film was set in a city, and so there were no green fields. In the end, the problem boiled down to the green of the shrubbery. I didn’t have a garden made to go with the house on the set, and while shooting on location I took care to see that the camera angle excluded trees and shrubs.

I took a job in a studio not because I liked photography but because I needed a job — I took a job in a studio only as a way to eat. Those were days when it was extraordinarily difficult to get a job, and you couldn’t pick and choose. I absolutely could not stand the films that were mass-produced by the studio in which I worked: tear-jerking melodramas and flavorless domestic dramas in which imbecilic men and women monotonously repeat exchanges of infinitely stagnant emotions. The places where these exchanges, which can only be called artificial, unfold are gloomy, decaying eight-mat drawing rooms and four-and-a-half-mat living rooms that contain such symbols of family stability as tea cabinets. In the background there was generally a totally commonplace garden. I hated such characters, rooms, and gardens from the depths of my soul. I firmly believed that unless the dark sensibility that those things engendered was completely destroyed, nothing new could come into being in Japan.

Just then, there began appearing in the actual cities of Japan scenes that differed from these. I remember vividly even now the excitement I felt the first evening I visited the clusters of high-rise housing built by the Japan Housing Corporation on the huge area of reclaimed land along the coast. The concrete walls cut across the sky in acute angles. The dreamlike lines of mercury lamps began to light up here and there. The long, long uninhabited corridors reverberated with a metallic clacking sound that was an echo of something I couldn’t identify. Ah! With this the sensibility of the Japanese will change! Japanese with a different sensibility will be born!

“When I thought about the lives being led by the people in those little boxes, a scream that life is meaningless pushed upward from deep within my breast.”

I visited a young official of the housing ministry at that government-built high-rise development. He was a friend from my student-movement days. He spoke passionately of his conviction that the founding of these dwellings would change the lives of the Japanese people for the better. By that time I had already stopped believing that the lives of the people could be changed for the better by a plan imposed on them by a government agency, so I wasn’t in complete agreement with him. However, because I was naively convinced that our sensibilities would probably be changed by these types of buildings, I responded to him cheerfully. It was an inspiring evening.

Seizing on the excitement of that evening, I spent about two and a half years in a fifth-floor studio apartment in government-built housing located right in the middle of a poor suburb on the outskirts of an industrial city. I don’t know whether my sensibilities changed while I lived in that three-mat concrete room. The view of the street from my fifth-floor window was sad — especially in the evening, when the matchbox houses bathed in the twilight appeared all too clearly to be more and more artificial. When I thought about the lives being led by the people in those little boxes, a scream that life is meaningless pushed upward from deep within my breast. I desperately resisted the temptation to throw myself out the window, and instead I decided to scorn the people leading those meaningless lives, myself included, with all my heart.

When I began shooting films, I decided to smear my films black with the feelings of scorn I had for those people and the simultaneous feelings of anger I had as one scorned. As far as possible, I made my heroes’ characters independent of their houses. Although you can say that essentially human beings are not separable from their dwellings, I tried to first establish my characters as individuals by choosing those who could actually exist separately from them. On a very technical level, I tried to eliminate completely all scenes with characters sitting on tatami while talking. It is difficult to shoot a composition with one person sitting on tatami and one standing, and if both are sitting down it becomes completely static. Also, it takes about twice as much time for a person sitting on tatami to stand up as it does for a person sitting in a chair. So, even when I did feature tatami rooms, I used chairs unmercifully.

At that time, the green of shrubbery was, for me, the root of many evils. No matter how severe a human confrontation you are portraying, it immediately becomes mild the instant that even a little green enters into it. Green always softens the heart — well, I don’t know about foreigners, but at least it does in the case of Japanese. This was definitely true, at least as I have observed it in frames on movie screens. For that reason, I banished all green.

“At that time, the green of shrubbery was, for me, the root of many evils.”

The green of pines is particularly bad. When that irregularly shaped green comes in, everything becomes ambiguously neutral. The sky above the green of the pines isn’t good either. The blue sky in itself is by no means a bad thing. The blue sky above the brown earth is sufficient to teach us the terror of human life. The blue sky beyond the green of the pines, the blue sky that you can just catch a glimpse of beyond your neighbor’s fence: those are the bad ones. They give the small satisfaction the feeling that this is good enough, the small sense of relief. In that film, therefore, I didn’t shoot the sky over the roofs of the houses or the sky outside the windows at all.

I don’t know whether or not the results were good. The film aroused a maelstrom of praise and censure and became popular anyway. No review, however, noted that I had repeatedly done the unnatural by banishing green and not shooting the sky.

Nearly 15 years have passed since then. It is almost 20 years since my evening of excitement about a high-rise development of reinforced concrete. The sensibility of the Japanese people is far from changed. Instead, as if to ridicule the excitement of an ignorant youth, they are burying every room of reinforced concrete in every possible mass synthetic chemical product, transforming these dwellings into the set for a truly mild new domestic drama.

My friend, formerly a young official at the housing ministry, returned to university-level research and is beginning a basic reexamination of the homes of the Japanese people.

If a film director on the threshold of old age thinks about the road his own work has traveled, he sees that with each new project the tendency to deny reality and play inside his own fantasies has grown stronger.

The destiny of the camera, however, is that it captures scenes of the real Japan. If so, to what extent can the landscape be modified as landscape? And to what extent can the artist, using the camera as a medium, convert the landscape into fantasies?

The film director approaching old age will soon no longer have the cheek, as in former days, to banish green and negate the sky. But he will strive to make his way into the endlessly minute aspects of reality, to discover and abstract his own fantasies there. And he will try to use the fantastic to thoroughly negate reality.

The film director on the threshold of old age must impose this sort of difficult task on himself because scenes that decisively negate reality do not exist in Japan today. Ambiguous Japan, where the instant that anything is made it seems to be completely buried in reality. This is particularly true of modern-day Japan. Is that really the nation’s destiny?

I have a definite distrust of the architects and others who create Japan’s scenery, particularly because they have not created even one place with scenery that adequately negates reality. But perhaps this is only the occupational resentment or prejudice of a film director who is trying to travel a difficult road and is getting tired.

(Kyosenzui, a periodical on flower arrangement, September 1974)

Nagisa Oshima was a pioneering Japanese filmmaker and a founding figure of the Japanese New Wave. This essay is excerpted from his collection of writings “Cinema, Censorship, and the State,” published in 1993. Oshima died in 2013.