The Perils of Being Paul Ehrenfest, a Forgotten Physicist and Peerless Mentor

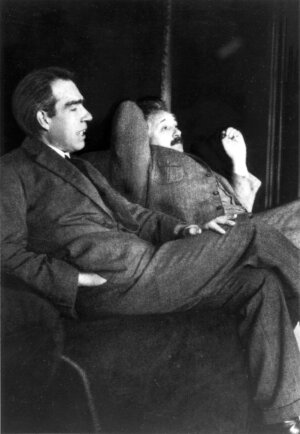

If we were to judge Paul Ehrenfest by the company that he kept, he was surely a great scientist. Albert Einstein once called him “the best teacher in our profession whom I have ever known.” Niels Bohr, a pioneer of quantum physics, was his close friend and frequent houseguest. And Enrico Fermi and Robert Oppenheimer, both of whom were leaders of the Manhattan Project, trained as postdoctoral fellows in Ehrenfest’s lab at Leiden University. Yet Ehrenfest’s personal contributions were much more modest. Today, he’s largely a forgotten figure, even among practicing physicists. Why, then, would he be considered a great scientist?

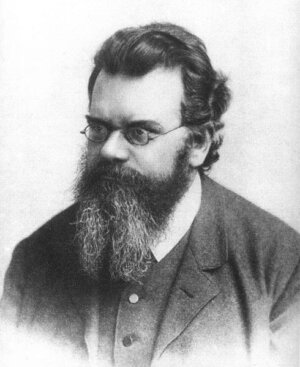

Any claim of scientific greatness on the part of Ehrenfest is inextricably tied to the legacy of his doctoral advisor, Ludwig Boltzmann. A titan of 19th-century physics, Boltzmann contributed significantly to our understanding of gases — a subject that might fail to capture the 21st-century imagination, but one that played a central role in the development of thermodynamics. By modeling a gas as a collection of atoms, governed by the rules of statistics, Boltzmann was able to establish a microscopic basis for the elusive second law of thermodynamics. The significance of this work has subsequently been found to extend far beyond the study of gases, to influence the fields of cryptography and economics and even the large-scale structure of the universe.

For Ehrenfest, however, the thrill of these discoveries had faded long before he ever met his advisor. The Boltzmann who trained Ehrenfest was a broken old man — still a celebrated scientist, both at home and abroad, but someone who was racked with self-doubt and -pity, a lesser mentor than Ehrenfest had likely hoped to find, particularly in an advisor whose discoveries had been so great. Their relationship never met its full potential. Even their classroom interactions seem to have been needlessly complicated. In one oft-told story, Ehrenfest earned Boltzmann’s favor by referencing his advisor’s work in an especially thorough manner for the rest of the class, to which Boltzmann is said to have jokingly replied: “If only I knew my own works that well!” But Ehrenfest is also remembered to have been a source of frustration for his advisor. In another classroom exchange, Boltzmann accused the young man of treating him like a lemon that could be squeezed dry for its juice. Ehrenfest had apparently wanted the professor to clarify some point of confusion. But his irrepressible need for dialogue — the very trait that would ultimately prove to be critical to his success — may have alienated him from the elder scientist.

In the end, however, it may not have mattered. Boltzmann killed himself just two short years after Ehrenfest earned his doctoral degree. And though it seems improper to find anything positive in a person’s suicide, it is clear in retrospect that Boltzmann’s death created an opportunity for Ehrenfest, one that appeared in the form of an unmet obligation. Shortly before his death, Boltzmann had agreed to contribute an article on the statistical foundations of the second law to the prestigious Encyclopedia of Mathematical Sciences. When that yet-to-be-written article was suddenly deprived of its slated author, the editor of the Encyclopedia, Felix Klein, needed a replacement, which prompted him to turn to Ehrenfest. Klein had met Ehrenfest at a Mathematical Colloquium where the newly minted Ph.D. had delivered an exceptionally clear presentation on the notoriously thorny subject of the second law. In that lecture, Ehrenfest had introduced a simple model that clarified many of the more controversial aspects of Boltzmann’s work. The model did not rely on overly complicated mathematics, but relied instead on a thought experiment in which balls were randomly selected to move back and forth between two urns; or in a slightly more playful version, fleas were allowed to jump back and forth between two dogs, leading to its unofficial designation as the dog-flea model. In either case — balls in urns or fleas on dogs — the model illustrated how particles are distributed throughout space and how that distribution changes over time. The model was characteristic of Ehrenfest’s approach, revealing his primary talent as a scientist. He was his generation’s foremost teacher.

The Mathematical Colloquium led to the Encyclopedia article. And the Encyclopedia article led to a professorship. And the professorship led to the friendships and collaborations for which he is known. True greatness, however, implies a legacy, a historical imperative. Was Ehrenfest really a scientist of that caliber? How talented a teacher must one be if he or she is to be recognized as great?

Consider this assessment offered by Arnold Sommerfeld, the man who trained Nobel laureates Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli. “He lectures like a master,” wrote Sommerfeld in Ehrenfest’s letter of recommendation for the position in Leiden. “I have hardly ever heard a man speak with such fascination and brilliance. … He knows how to make the most difficult things concrete and intuitively clear. Mathematical arguments are translated by him into easily comprehensible pictures.”

Ehrenfest’s methods outside the classroom were also noteworthy, particularly for the intensity that he displayed in training his graduate students. One of those students, George Uhlenbeck, described his educational experience in Leiden this way: “He worked essentially always only with one student, and that practically every afternoon during the week. He discussed with him either the problem on which he was working or recent papers in the literature which he wanted to understand in detail. It went fast,” Uhlenbeck added. “At the end of the afternoon one was dead tired. … The wonder was that after a while the tiredness disappeared, and after a year one worked almost as equals.”

When the eminent scientists of the 20th-century met to build the foundations of modern physics, they wanted Ehrenfest in the room.

In Uhlenbeck’s case, he not only survived this apprenticeship, but he and fellow student Samuel Goudsmit actually discovered something fundamental — the property of electron spin. Yet he may not have made that discovery had he not first endured the rigors of Ehrenfest’s undivided attention. It’s also revealing to note that Uhlenbeck was given due credit for his discovery. A lesser scientist than Ehrenfest may have misrepresented the student’s work as his own, robbing the student of future accolades. But Ehrenfest was apparently not just a great scientist. He was also a good man.

There is perhaps no more compelling character witness for this good man than his friend and colleague Albert Einstein. In his book “Out of My Later Years,” Einstein described Ehrenfest as someone who was “passionately preoccupied with the development and destiny of men, especially his students. To understand others, to gain their friendship and trust, to aid anyone embroiled in outer or inner struggles, to encourage youthful talent — all this was his real element, almost more than immersion in scientific problems.” Einstein further noted that Ehrenfest “always brought clarity and acuteness into any discussion. He fought against fuzziness and circumlocution, when necessary employing his sharp wit and even downright discourtesy.”

When the eminent scientists of the 20th-century met to build the foundations of modern physics, they wanted Ehrenfest in the room. His colleagues realized that scientific revolutions need not just revolutionary minds, but also discerning thinkers who can organize the emerging narrative. And Ehrenfest clearly exemplified this latter category. His biographer Martin Klein described his role this way: “No man was more deeply engaged than he in the struggle to create the concepts of twentieth century physics, and no man was more fully committed to maintaining clarity and intelligibility in the flood of new developments. His efforts were recognized by the informal title his colleagues conferred upon him: the conscience of physics.”

Unfortunately, Ehrenfest was not content to be the mere conscience of physics. He longed to play a different role, to earn a place among its revolutionaries — a distinction that appeared more and more unlikely as he grew older. A younger generation (a generation that he had helped to train) was changing the nature of physics, and in ways that seemed to diminish the value of his skill set. For Ehrenfest, physics had always been something that he could visualize. It yielded to concrete examples. It was not just a set of self-consistent mathematical statements. Meaning and understanding were embedded in the mathematics. But a younger generation had found success by turning to increasingly esoteric methods. And as physics began its irreversible slide toward the abstract, Ehrenfest was seemingly left behind.

He did not hide his sense of bewilderment, nor his sense of shame. His shame, however, was unfounded and contradicted by his everyday experience. The physics community continued to hold him in high esteem; his colleagues still sought his counsel. Yet he felt excluded from the conversation, and a sense of inadequacy, which had always lingered near the surface, eventually began to flourish. In a letter to several of his former students, he wrote: “Every new issue of the Zeitschrift für Physik or the Physical Review immerses me in blind panic. My boys, I know absolutely nothing.” His former students reassured their mentor that he did in fact know a great many things. The questions that he found to be most puzzling — those related to the emerging quantum theory — were significant hurdles for the physics community as a whole. They encouraged him to speak more publicly about the challenges presented by the quantum theory, which he did, but only after some prodding. He eventually contributed an article to the Zeitschrift für Physik (one of the two journals that immersed him in blind panic). The article was titled Some Inquiry Questions concerning Quantum Mechanics. Responses to the article confirmed that Ehrenfest’s “inquiry questions” were not simple points of confusion, a burden to one man. His questions actually pointed the way forward. And so in his characteristic way, Ehrenfest had once again, by asserting a need for clarity, served as an indispensable guide.

“Every new issue of the Zeitschrift für Physik or the Physical Review immerses me in blind panic. My boys, I know absolutely nothing.”

But his need for clarity would eventually take its toll on the man and deprive the physics community of its foremost teacher. Ehrenfest would follow Boltzmann’s path to its tragic end. He would not, however, make the decision rashly. The letter that’s often cited as his suicide note was actually written (but never sent) a full year before his death. In that letter, he wrote:

“My dear friends: Bohr, Einstein, Franck, Herglotz, Joffé, Kohnstamm, and Tolman! I absolutely do not know any more how to carry further during the next few months the burden of my life which has become unbearable … it is as good as certain that I shall kill myself. And if that will happen some time then I should like to know that I have written, calmly and without rush, to you whose friendship has played such a great role in my life. … In recent years it has become ever more difficult for me to follow the developments [in physics] with understanding. After trying, ever more enervated and torn, I have finally given up in DESPERATION. … I have no other ‘practical’ possibility than suicide … Forgive me.”

A year later, his outlook had not improved. And in the end, it was not just a matter of physics. There was also a failed marriage, and a Nazi party in neighboring Germany, and the subsequent emigration of his friend Albert. All of these factors likely contributed to the tragedy that occurred on September 25, 1933. Ehrenfest traveled that morning to Amsterdam where first he met with a former student. Although he planned to kill himself later that day, he apparently needed to play the role of mentor one last time. After the meeting, he went to the Institute for Afflicted Children where his 15-year-old son Wassik lived. Wassik had recently been transferred to Amsterdam from a German clinic. His son had Down syndrome, and the Nazi party had seized power earlier that year. After arriving at the institute, Ehrenfest met his son in the waiting room. There he shot Wassik in the head with a pistol, and then he killed himself. It was an unfathomable end — an inconceivable act that betrayed a meaningful life. Paul Ehrenfest was a great scientist. He was not a good judge of the life he had lived.

Eric Johnson is Chair of the Department of Chemistry at Mount St. Joseph University in Cincinnati. He is the author of “Anxiety and the Equation: Understanding Boltzmann’s Entropy.”