The Man Who Invented Times Square: O.J. Gude and the Birth of the Spectacular

They have reigned as the star attraction, always — the flashing, pulsating, sometimes disorienting messages radiating in all directions from the supersized signs in Times Square. As this illuminated theater of American commerce evolved over time, it shaped an imagistic personality for the district, one that thoroughly embodied the theatricality of the place. It was not a place of subtlety. The outside space was a fantastical show — a visual maelstrom free to all who came, ever changing moment by moment. Constantly heightened by the ambition of successive innovators abetted by advances in display technology, the robust energy and dynamism of the commercial culture of Times Square brought into being a singular place where advertising spectacle became entertainment, where private interests transformed an open space into an arena for visual pleasure of enduring appeal to tourists and locals alike.

Times Square owes much of its storied history to a physical anomaly: the bowtie configuration of streets created by Broadway’s diagonal intersection with Seventh Avenue. The geometry of this space with its twin goalposts of visibility at either end formed a natural stage for the theatricality of bright lights. The long sight lines along Broadway and Seventh Avenue are exceptional. Walled by theaters, restaurants, retail shops, and small business buildings, the open space was “especially well-suited for squinting at signs,” writes Sandy Isenstadt in his book on the architecture of electric light. Before they were replaced by office towers, the rooftops of two- and three-story buildings were easily transformed into sky-hugging metal frameworks for mounting supersized billboards and flashing signs that drew pedestrians to the square. From the center of the bowtie at 45th Street, “looking either north or south, the space opens up like the field of vision itself. With signs situated on façades or rooftop scaffolds, views were encircling and unimpeded,” Isenstadt explains. It “resembled an arena, though inverted, with the audience at the center and the performance along the periphery.”

“Everybody must read them, and absorb them, and absorb the advertiser’s lesson willingly or unwillingly”

The Times Square bowtie offered advertisers a perfect showcase — a generous physical space tailor-made for product ads — and it would not take long for the nation’s commercial purveyors to understand its potential, especially after electricity supplanted gaslit signs. Broadway was New York’s first electrified street (1890), and soon the dark, off-putting urban nighttime was being transformed into a sparkling environment of incandescent lights. But it took the entrepreneurial actions of Oscar J. Gude to make Times Square the most dramatic gathering place of all.

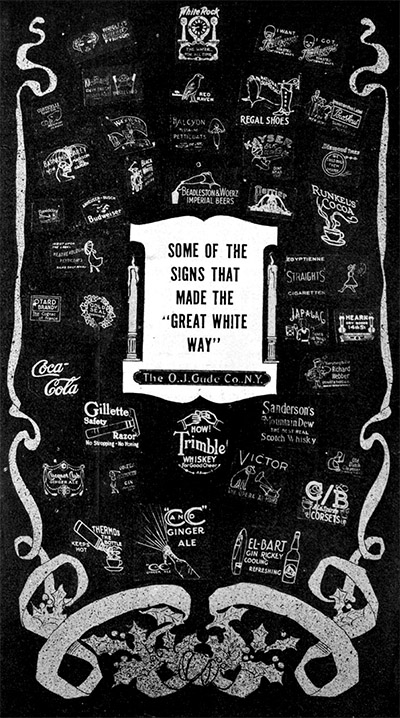

Gude invented the “spectacular,” an enormous electric sign consisting of hundreds of light bulbs wired to elaborate circuits which dictated animation patterns and different lighting effects. The goal was to stop people in their tracks, to sell through entertainment. Electric advertising “literally forces its announcement on the vision of the uninterested as well as the interested passerby,” he said. “Everybody must read them, and absorb them, and absorb the advertiser’s lesson willingly or unwillingly.” By 1913, Times Square dazzled with hundreds of thousands of bright lights, emitting an intense glow that gave the district its nickname, “The Great White Way.” (The slogan, attributed to Gude, conveniently omits the fact that the blazing canyon of lights included many signs with colored as well as white lights.)

Drawing huge crowds of lingering, gaping consumers, Gude’s spectaculars were legendary. His first — the Trimble Whiskey sign (1904), placed at the central triangular block at 47th Street for maximum display — was visible for many blocks. The combination of Gude’s marketing brilliance and his creative designers produced a “constantly changing roster of enormous moving light displays in the sky about the square. Within a few years,” Darcy Tell wrote in “Times Square Spectacular: Lighting up Broadway,” “Gude almost single-handedly transformed Times Square into America’s most important outdoor advertising market.” Between 1904 and 1917, his company put up approximately 20 large spectaculars in Times Square, each more elaborate and dazzling than its predecessor.

A charismatic promotional genius, Gude was the son of immigrant parents from Germany who started as a sign hanger and bill poster, before opening his own outdoor advertising business in 1889 to design marketing campaigns for corporate clients selling branded commodities. His success built on aggressive salesmanship combined with high-quality visual images. In a strategic maneuver, he bypassed local business and went directly to national companies when looking for clients, convincing them that a properly placed sign would reach a huge audience of entertainment seekers coming to Times Square on foot or by the new subway at 42nd Street. He gained control of a network of the most visible rooftops around the square, and with his designers applied technological breakthroughs of the day that allowed groups of connected bulbs to be turned on and off in sequence and lights to be dimmed or raised.

The result was cinemalike actions in lights: A girl performed stunts on an electric tightrope. A polo player galloped on a horse and wacked a ball in an arc above Broadway. Boys boxed in their underwear. The signs promoted almost every product imaginable: safety razors, dental cream, cars, tires, bran flakes, coffee, whiskey, gin, cigarettes, chewing gum, movies and shows, gloves, and underwear, among many others.

Gude’s truly memorable and remarkable (and expensive) spectaculars came to dominate the growing nightscape of the square: the “coyly erotic” Miss Heatherbloom (1905), the 50-foot Petticoat Girl, who struggles under an umbrella in an electric rainstorm as her dress whips up to reveal her petticoat and shapely legs; the frolicking Corticelli Kitten (1912) tangling with a spool of thread in different locations; the flowing fountains of sparkling White Rock Table Water (1915) glittering in changing pastels; and one of the square’s longest-running spectaculars, the block-long Wrigley’s Spearmint Chewing Gum sign (1917–1923) atop the Putnam Building, a six-story office building on the west side of Broadway between 43rd and 44th Streets built by the Astor Estate in 1909. This was Gude’s most elaborate animation: 70 feet (eight stories) high and 250 feet long, boasting more than 17,000 white and multicolored lamps with flowing fountains, peacocks with 60-foot-long tails, flora and foliate motifs, and six prancing Spearmen, each measuring 15 feet high, who went through 12 calisthenics, which the public promptly dubbed the “Daily Dozen.” More than the flavor of gum, the brand itself was being advertised. “The largest electric sign in the world advertises WRIGLEY’S. . . . The sign is seen nightly,” its 1920 advertisement boasted, “by approximately 500,000 people, from all over the world” passing through Times Square.

The mystique behind outdoor advertisements aimed to evoke something beyond the prosaic commodity. For White Rock Ginger Ale, “the water for all time” (1910), Gude designed a large clock that changed color every few seconds bracketed by flowing fountains of light. “The flowing fountains and colorful lights of the White Rock sign suggested that Times Square was an exotic and magical paradise existing outside the constraints of everyday life,” wrote the curator for the wall panel in the New-York Historical Society’s 1997 exhibition Signs and Wonders. The use of color, light, and exotic motifs was a popular device in stores, restaurants, and nightclubs. “Using these devices in advertisements imbued products with a mystique . . . and suggested that consumers could obtain that exoticism by purchasing the product.”

Never subtle, the commercial bottom-line aesthetic that came to define Times Square was not appreciated by the city’s elite or by civic organizations promoting the “City Beautiful.” They railed against “sign evil” — a growing aesthetic problem of large-scale billboards proliferating indiscriminately all over the city since the turn of the century. Sufficiently powerful, the public outcry convinced Mayor William J. Gaynor (1910–1913) to appoint a Billboard Advertising Commission (1913) to investigate the problem and issue recommendations, which it did, though none were adopted. “The ubiquity of these advertisements is an aggravating phase of the situation,” the commission’s report complained. “They are no respecters of place. They are not confined to the unimproved tracts and rubbish yards on the outskirts of the City. On the contrary, they are thrust into the finest vistas which our public places present.” Of course, that would be where the most eyeballs would see them.

Never subtle, the commercial bottom-line aesthetic that came to define Times Square was not appreciated by the city’s elite or by civic organizations.

Fast forward to the 1920s. However much the businessmen and merchants of Broadway were benefiting from the economic power of the effusion of color and light that brought thousands upon thousands to Times Square, the same anti-billboard forces pressed on. “Throughout the twenties,” historian William Leach explained, “a battle was waged in Manhattan between rival trade associations over signage restrictions. On one side was the Broadway Association, which wanted no controls whatsoever placed on signage; on the other side was the grandiose and aggressive Fifth Avenue Association.” Fearing that the electric signs would spill out of Times Square, where they had been allowed under the city’s new zoning ordinance of 1916, the Fifth Avenue Association fought for control from 1916 onward, insisting that all projecting and illuminated signs be banned on Fifth Avenue from Washington Square to 110th Street.

The merchants of Fifth Avenue “wanted the patronage of the tourists who were attracted to New York by the lights of Times Square; and they certainly had nothing against commercial light and color.” What they did not want was a “‘carnival spectacle’ that might bring an influx of the ‘wrong kind of people’ into the Avenue on a daily basis, an influx that might jeopardize real estate values and undermine the control these merchants had over their property.” In 1922, the Fifth Avenue merchants succeeded in convincing the Board of Alderman to pass an ordinance that put strict controls on signage everywhere around Times Square, which had the effect of intensifying the glitter and concentrating it in that one sanctioned area, where it would have a “carnival field day.”

Decade after decade the intense illumination of commercial signs in Times Square speaks to the magical energy of the city, the serendipitous encounters among strangers mesmerized by the scope and vitality of New York. It is a strand of the city’s DNA, the embodiment of its distinctive commercial energy — rooted in an ability to innovate beyond what proved successful before.

Lynne B. Sagalyn is Earle W. Kazis and Benjamin Schore Professor Emerita of Real Estate at Columbia Business School, as well as a real estate professional. She is the author of “Power at Ground Zero: Politics, Money, and the Remaking of Lower Manhattan,” “Times Square Roulette: Remaking the City Icon,” and “Times Square Remade: The Dynamics of Urban Change,” from which this article is adapted.