‘That was our beach’: Notes on Fred Conrad’s Iconic 1977 Photograph

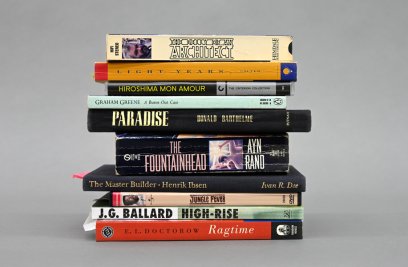

“The Beach is always there: you just have to conceive of it.”

–Zadie Smith, “Find Your Beach,” New York Review of Books

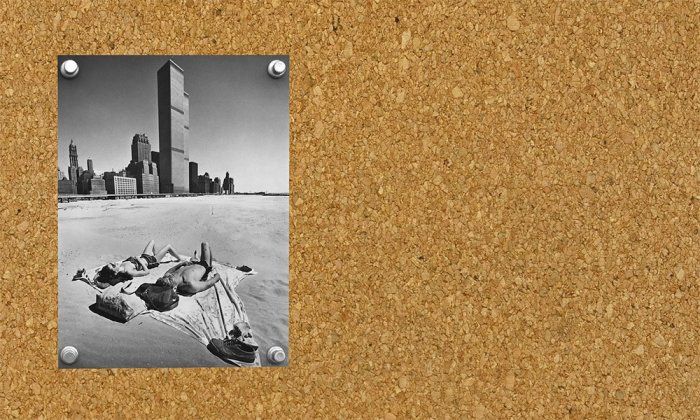

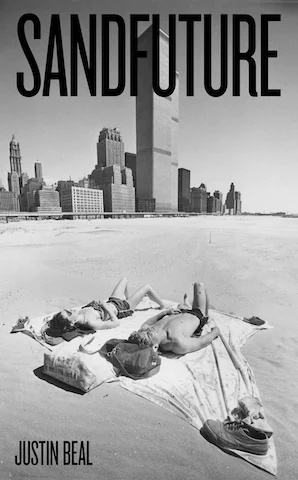

On a Sunday morning in May of 1977, Fred Conrad photographed a young couple lying in the sun on a floral bedsheet stretched between canvas shoes at the foot of the World Trade Center. The photograph, which ran below the fold on the front page of the New York Times the following morning was among the first of hundreds shot by Conrad during his 37-year career at the paper.

I love this image, not only for its spectacular perspective — it is difficult to comprehend at first, like a collage of two images of irreconcilable scales — but also for the way it captures the city at an inflection point in its history. New York had narrowly escaped bankruptcy, but seven years of economic downturn and severe cuts to municipal services had driven morale among city employees to a historic low. Murder rates had quadrupled in a decade and the first “Son of Sam” letter, found at a murder scene in Baychester several weeks earlier, had the city on edge. Tensions would reach a boiling point several weeks later, on a steamy July night when a citywide blackout led to looting and arson after thousands of off-duty police officers ignored orders to report to work. For now, however, things were quiet. It was Sunday morning and the skyline in the distance, its derelict highway and blank office buildings, looked abandoned. This couple could be the last two humans on earth, ecstatic and oblivious, deserted on a beach that seems to stretch to the distant stanchions of the Verrazzano Bridge on the horizon.

The Port Authority had to build a massive watertight foundation in which each tower would be anchored “like a tooth in a bed of spongy landfill.”

The World Trade Center was conceived by David Rockefeller, designed by Minoru Yamasaki, and built by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Rockefeller, whose family had significant real estate holdings in the financial district, built the towers in an effort to curb the gradual exodus of white-collar workers from Wall Street office buildings to midtown landmarks like the Chrysler and Empire State buildings. After years of fits and starts, lawsuits and backroom deals, work began in April 1963, when the New York State Court of Appeals dismissed a case filed by local electronics merchants and allowed the Port Authority to take all 16 acres of the proposed superblock by eminent domain. Much of the land beneath the proposed site had once been riverbed, so to keep the Hudson at bay, the Port Authority had to build a massive watertight foundation, over 3,000 feet in circumference and about 60 feet deep, in which each tower would be anchored, as Glenn Collins wrote in the New York Times, “like a tooth in a bed of spongy landfill.”

When the newly elected mayor John Lindsay threatened to hold up the project unless the Port Authority agreed to pay additional real estate taxes, construction halted until it was agreed that in lieu of taxes, the Port Authority would use the rubble excavated from the foundations of the towers to create a new landfill immediately west of the site on the Hudson River and gift the reclaimed land to the city. Work proceeded and when the perimeter wall of the foundation was completed in the spring of 1968, a caravan of yellow Euclid dump trucks began hauling earth from the dry 11-acre void to cofferdams waiting on the bank of the Hudson.

The World Trade Center officially opened on a rainy morning in April 1973. Then, that fall, the members of OPEC declared an oil embargo against nations that supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War and the price of gasoline skyrocketed, sending the U.S. economy into a tailspin. Economic stagnation combined with plummeting tax revenue resulting from an exodus of wealthy (and largely white) residents left New York in an intractable financial crisis. By 1975, the city had run out of money to pay for normal operating expenses and faced the prospect of defaulting on its obligations and declaring bankruptcy.

Ultimately it was the financial sector, not the government that bailed the city out. Governor Carey assembled an advisory board of bankers and businessmen led by Lazard Frère’s Felix Rohatyn. In September of 1975, this “Municipal Assistance Corporation” became the “Emergency Financial Control Board” and the municipal government effectively ceded control of the city to a crisis regime. When the retrenchment put the development plan for Battery Park City on hold, the landfill was covered with a sandy overburden dredged from the bottom of Lower New York Bay. The reclaimed land became an ersatz beach, an otherworldly expanse of urban dune at the western boundary of the financial district. And so it was on that warm Sunday morning when Conrad took the photograph of the couple lying on the beach.

That beach remained undeveloped for six years until the New York economy began to show signs of recovery in the early 80s. During that time the Port Authority reinterpreted its mandate to rent only to businesses “involved in world trade” to include those servicing the burgeoning global financial sector and revenues tripled between 1978 and 1983. By abandoning the pretense of a “vertical port,” the Port Authority had finally transformed the towers’ image from a government boondoggle to an international icon of financial excess. By the time “Bright Lights, Big City” was published in 1984 with Marc Tauss’ painting of glowing silhouettes of the World Trade Center on the cover, the towers meant something different. Al Smith and Fiorello La Guardia’s vision of a “workers’ paradise” had died and something new had risen in its place. The port had long since moved to New Jersey. Rohatyn’s intervention had set the city on a new trajectory. Knowledge had replaced labor. Services had replaced goods. An industrial city had reinvented itself for an information economy and by the turn of the century, Mayor Michael Bloomberg would preside over a city (or at least a borough) he described, without irony, as a “luxury product.”

In October 2014, Zadie Smith wrote an essay for the New York Review of Books trying to reconcile the contradiction of a city that is both an epicenter of literary and artistic production and increasingly inhospitable to the “vanishingly small subset of rent-controlled artists and academics” who make that possible. This is not nostalgia — Smith is careful to note that artists have “always worked off the energy generated by this town, the money-making and the tower-building as much as the street art and underground cultures” — so much as a reckoning with the reality that each subsequent wave of economic inertia makes it slightly harder for those artists to keep a foothold on an island that has always been such a powerful crucible of creativity.

Smith borrows her title, “Find Your Beach,” from a beer advertisement painted on a brick wall across the street from her Soho apartment. It is a perfect metaphor — a late capitalist inversion of the Situationist call to action, sous les pavés, la plage. Here, the beach is not a place, it is a mental construct. It is happiness as an act of will. It does not matter that there is no beach — “the beach is always there: you just have to conceive of it.”

Here, the beach is not a place, it is a mental construct. It is happiness as an act of will.

In the five years I spent working on “Sandfuture,” I never managed to find the name of the couple in Conrad’s photograph. Then, just a few weeks after the book came out, I found a reproduction of the picture in “New York Rising: An Illustrated History of the Durst Collection,” edited by Kate Ascher and Thomas Mellins. The caption referred to a woman named Suellen Epstein. I found Epstein’s contact information online and sent her a copy of my book and a note proposing that we meet for coffee. Several weeks later I received a reply in the mail, confirming that it was in fact her on the cover and saying that she would be happy to get together after pandemic restrictions eased.

I met Suellen for a coffee in Tribeca in June, a few blocks from the loft where she has lived and run a tumbling studio for children since the late seventies. To mark the occasion, she arrived wearing the same pair of Ray Bans she wore in the photograph, before replacing them with a pair of prescription glasses in translucent blue frames. She was working as a dancer when the photograph was taken and the man by her side was James Biederman, a sculptor who was her boyfriend at the time and whom, though they are no longer close, she “still sees around occasionally.”

We sat on a bench in a shady corner of City Hall Park where she is an active member of one of two volunteer conservation groups. We spoke for over an hour about public art and the bureaucratic inefficiencies of the New York City Parks Department. She asked about the Venice Biennale, from which I had just returned and which she was looking forward to seeing later in the summer. In time, we discovered that a friend of mine had studied at her studio as a child growing up in Tribeca and that her son was now Suellen’s student as well. Inevitably, the conversation turned to the subject of how the neighborhood has changed in 45 years. The copper top of the Woolworth Building and the stepped terraces of the Telephone Building are still there, but little else of the skyline remains — the elevated Westway is gone, the landfill has long since been covered by condos and the World Trade Center has been replaced with a cluster of generic new office towers. She laughed when I pointed out that she was still there looking every bit as comfortable in her surroundings as she did in Conrad’s photograph.

When I asked her how she and James found themselves on the bank of the Hudson that particular morning her answer was simple: “that was our beach.”

Justin Beal is an artist and a writer based in New York. Portions of this article are adapted from his book “Sandfuture.”