How Not to Die From an Overdose: Nancy D. Campbell on Harm Reduction and Naloxone

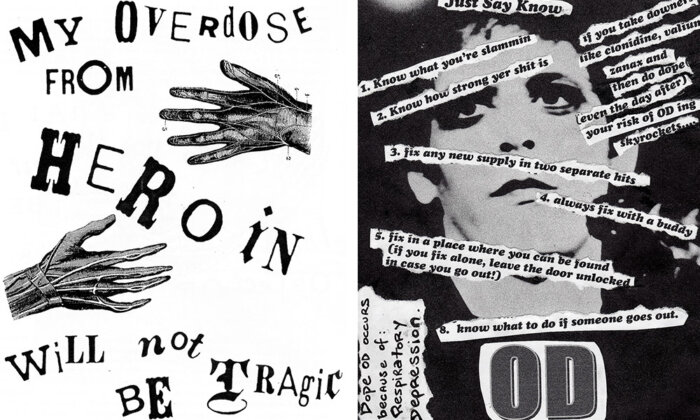

Unlike other forms of protest, direct action does not seek to convince onlookers, politicians, or lawmakers of the virtues of a certain position. Rather, it simply addresses the problem at hand. Perhaps it makes sense that one of the most salient examples of direct action was born from the time-precious struggles against the spread of HIV/AIDS in the 1980s. Who has time to appeal to outsiders when your community is dying?

Now, in the face of a growing crisis of opioid overdoses, organizers are again applying the principles of direct action and harm reduction to save lives. In the conversation that follows, Nancy D. Campbell, the author of “OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose,” and I discuss the history of the opioid epidemic and how it vividly intersects with U.S. politics and drug policy.

A stream and lightly edited transcript of the podcast, which was recorded in September 2020, can be found below. You can subscribe to the podcast at Apple, Spotify, or Podbean.

Sam Kelly: How does Naloxone stop people overdosing?

Nancy Campbell: Naloxone is interesting because it’s a largely inert substance, unless you already have opioids in your system. If you have an opioid sitting on the opiate receptors in your brain Naloxone will just knock the opioid off the receptors because it has a stronger affinity for those receptors. It’s like a golf club, hitting a golf ball off the tee.

It’s pretty simple in a lot of ways. Its complexities, of course, are social, political, legal.

SK: Could you clarify which drugs are being discussed when you refer to opioid overdoses?

NC: Overdose is a general term that’s applied to a lot of different drugs. Many of which we don’t think of as drugs you can overdose on. For instance, there’s lots of people who overdose on anticoagulants and die.

However, what I’m talking about are opioid overdoses. Specifically, heroin and pharmaceutical opioids such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl, which is a synthetic opioid. Until fentanyl, all opioids came from the opium poppy. Which is important because the ability to synthesize opioids shifts a long global history of the opioid as a commodity. Production is no longer limited by the environment in which poppies can be grown.

Fentanyl has a much shorter history and makes up close to 95 percent of the U.S. heroin supply, and increasingly, in other places. Unlike the U.K., which has historically had access to high grade heroin, places that don’t have that kind of a heroin market opt for fentanyl.

SK: At what point did Naloxone start getting used in response to people overdosing?

NC: My book “OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose” tells the story of how Naloxone goes from a drug that is locked within a medical enclave to one that’s used by activists.

Naloxone was synthesized in the early 1960s, and approved in 1971. Unfortunately, the pharmaceutical company that got the patent on Naloxone didn’t see a market for it. The social movement that precipitated the adoption of the drug, is the HIV/AIDS activism movement (ACT-UP, etc.) They foregrounded the notion of harm reduction. In other terms, they began to think about how to reduce blood-borne virus transmission. Once it was established that intravenous drug users were transmitting HIV, they organized needle and syringe exchanges. These were illegal in the United States. Unlike in the U.K., where harm reduction has been infused into the healthcare system. We didn’t do that in the United States.

The United States harm reduction movement had to be an underground movement. That meant that it took a long time for people to realize that they could do something with Naloxone. Not until the mid to late 1990s did the American social movement begin to realize, we could give Naloxone out to people and teach them how to use it.

“[Harm reduction] is the opposite of what most people who use drugs encounter. They encounter an alienating and isolating society.”

One of the big mysteries of this book is why did it take so long for an essential medicine like Naloxone, to get to the people who needed it most? Doctors could prescribe Naloxone, but the fact is, they didn’t. Even if they knew somebody was an opioid user, even if they knew that they had someone prescribed high dose opioids for cancer pain or terminal illness, they didn’t give out Naloxone.

A lot of overdose deaths in the United States happen to people who are taking opioids as prescribed. Many people don’t realize this. Even the people taking the drugs, because it’s people who don’t see themselves as a person with an addiction. It’s people who are cancer patients or terminally ill who need access to Naloxone because they’re highly at risk of an overdose.

SK: I just want to pick up on the term “harm reduction.” Could you explain what that term and attitude encompasses?

NC: Recently, I did an interview with the former director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse in the U.S., and he called harm reduction a dirty word. Which It was, up until the early 2000s.

The attempts made by the U.S. to lead a global prohibition regime (where abstinence only is the only way) has made it very difficult for people in the harm reduction movement to make inroads. The term itself has had much more provenance in Europe, the U.K., and Australia, than it did in the U.S.

In the rest of the world, it has a less provocative quality. Whereas in the U.S. if you say harm reduction it’s like you’re calling everyone to the barricades. In the U.K., you were able to integrated qualities of harm reduction into the healthcare system. The inclusion of harm reduction nurses for example. I had never heard of a harm reduction pharmacist until I was in Scotland.

The principles of harm reduction are actually very practical. It’s about the personal steps you can take to reduce harmful consequences, in this case of drug use. What can be done to prevent the most harmful harm of all: death.

SK: It’s interesting that you use a term like ‘pragmatic.’ A lot of drug policy is based on judgment but what I find so instructive about the people in your book is that they attempt to move past judgment. And whilst some might see that as naïve or utopian. It’s actually the pragmatic attitude. Can you explain why harm reduction is not just an ethical or moral stance, it’s actually the most pragmatic one too?

NC: I think the affective and emotional tone of harm reduction is important too. People who use drugs are met with such judgmental-ism on so many levels, from people they love, from family members, and close friends.

I talk about Naloxone as a technology of solidarity in the book. Solidarity, the idea that someone accepts you for who you are, is picked up intangibly. To know that someone cares about you, to the extent that they organize harm reduction and they show up day after day, week after week, to make sure that you’re okay, and that you have your basic needs met. I think that’s what harm reduction is. It’s the opposite of what most people who use drugs encounter. They encounter an alienating and isolating society. As drug treatment has been able to migrate towards harm reduction, it’s become more effective.

That’s where the pragmatism comes in. When you start looking at improved results, that’s not just warmer and kinder. That’s impacting outcomes and results in ways that you weren’t doing before you adopted that attitude. Public health can be morally judgmental, it can be delivered in morally judgmental ways. We have many historical examples of public health measures that people refused to accept and take up, because it was delivered with an attitude of condescension. Harm reductionists turned that on its head.

Public health advocates didn’t jump on the harm reduction bandwagon at first, because it conflicted with what they were doing. It was closer to social work, and some of the principles of social work that were embedded in harm reduction practices.

There are real contradictions, in how healthcare is organized. It’s no wonder that people pick up on them and feel them. Maybe people don’t know the whole history of public health or the whole history of harm reduction. But they can tell, people can tell if you’re morally judgmental, if you’re condemning their behavior, if you’re displacing them. If you are removing them from public parks or taking all the benches away, or installing hostile architecture so that they cannot rest. All of those are the opposite of harm reduction. It’s an expansive worldview, and it can shift how you see things.

“People can tell if you’re morally judgmental, if you’re condemning their behavior, if you’re displacing them.”

SK: Can I ask you more about what harm reduction organizing look like? In communities experiencing overdosing crises, how are people organizing themselves?

NC: Harm reduction always has a local flavor. It’s organized differently, in different places. For example, in San Francisco or Seattle, there’s a harm reduction infrastructure already in place which has been assembled over years, in cooperation with law enforcement, with the city, with the municipality. In this instance, there are health care practitioners involved on site.

Those examples are really different from the smaller cities where harm reduction takes place through needle exchange. You also you see harm reduction that addresses lots of different kinds of basic needs. The need for food might be addressed by the organization of a community garden, urban sustainable agriculture.

These places usually look like tents and encampments, where supplies are given out. They almost look like a farmer’s market. They become meeting grounds, common grounds. And of course, because of their clientele, they are organized in a way to make sure that people’s basic needs are being met. For example, arranging the presence of people who can help gain access to social housing. So sometimes they take place in homeless healthcare settings. It can vary quite a bit according to the needs and the character of a place.

SK: People tend to find their way into these conversations via the news cycle, where complex things get boxed up. For some people, those boxes look like “the war on drugs” or “the opioid crisis.” And it strikes me that, the way those things are packaged reflects the dynamics of race and racism.

How do you think through those issues? Do you think the widespread attention to something like “The Opioid Crisis” reflects a disinterest in drug policy when it has affected black and brown communities?

NC: I’ve been studying the racialization of drug policy for the past 30 years. And for me, the war on drugs starts in the 1950s and not in the 1970s. In the United States heroin markets spring up in urban communities of color at that time and there begins a process of racialization and criminalization of drug policy. Mandatory minimum sentences are introduced and penalties are increased. Eisenhower announces a war on narcotic addiction in 1954. That war became endemic in urban communities of color. That war is still there today.

This is also when the seeds of mass incarceration are sown in the 1970s. New York State, and California in particular begin to incarcerate drug users and traffickers for longer periods of time. I think it’s really important for us to understand the opioid crisis as something built upon that endemic history.

“Eisenhower announces a war on narcotic addiction in 1954. That war became endemic in urban communities of color. That war is still there today.”

Now this crisis is portrayed in the media as very white. There’s a lot of analysis out there on the produced whiteness of the opioid overdose crisis. But in my book, I try to be very careful to tell that longer story, because it was never the case that black and brown communities were not affected.

Drug policy changes all the time. It changes and yet, it is locked in place by a larger regime that refuses to change. Global drug policy, particularly the U.S. hegemony over global drug policy, has prevented change toward the kind of policy that I’m talking about in the book.

We’re at a point where we need to see the ways in which criminalization and medicalization inform each other. Criminalization has often targeted black and brown communities whilst medicalization has tended to target white communities. Why is that? Racism is a good answer. The institutionalization of that kind of racism is a good answer to why medicalization and criminalization occur with different targets.

Since the 1950s, there’s been convergence between those two processes. The uptake in pharmaceuticals like opioids are an instance where you can see the convergence between criminalization and medicalization. The differential effects on different communities. The fact is, they work together to produce the untenable situation that we are now in.

SK: There’s a binary opposition for a lot of people between a drug user and a medical expert, someone who has an addiction and an activist, or a drug dealer and a first responder. How important it is that those categorizations get complicated?

I ask that in both the sense of representation, but also how important is it that people who have an addiction, and are in recovery, can take their experiences and give them meaning in the activism that they do?

NC: I think that those categories help people keep intact their worldviews, when reality is usually more complex than they want to acknowledge. There are usually more exceptions to the rules that we have about how particular people should behave. For example, law enforcement would like to think that dealers are separate from users. That traffickers are separate from addicts. And to not recognize the complexities, the economic complexities of the economy that they are dealing with.

I was having a conversation with a DEA agent who talked about how terrible it was that dealers were giving out Naloxone, becoming harm reduction activists, and preventing the deaths of their customers. To me, that seems like a very hopeful thing. I think that everyone should have Naloxone, if they are using an opioid or even if they’re using a methamphetamine that has fentanyl in it. People should have Naloxone and whether it’s dealers, officers, or sheriffs handing it out, that all seems like a good thing to me.

This is often very complicated when consider identities, like mothering or parenting, in relation to people who are using drugs. Then you begin to see, there are a lot of complexities here. Why are people doing what they’re doing? People don’t always know why they’re doing what they’re doing. I’m interested in how the complexity of the current moment has been produced over time. I’m really interested in the multi-layered and intersectional identities of people.

It does make it hard to write short books though. This is a longer book, because I do try to be careful about how I’m talking about people, many of whom are still alive, and many of whom have very complicated motivations for entering the sector.

I do think harm reduction is important to people that come to this work having been in long-term recovery. There used to be a lot of confusion about whether people who are in long-term recovery could also be harm reductionists. But I think that there are much more forgiving, and much more humane and compassionate identities that have now evolved in the recovery community. Because now you begin to see this complex cross-fertilization, really, between recovery and harm reduction.

SK: We’re all living through this pandemic and I think that there’s a lot of crises, that are coming to a fruition at the moment, whether they be economic, ecological, political.

What lessons can be drawn from the work of the people in your book? What can these grassroots, decentralized responses, offer when we start to think about other problems?

NC: Naloxone is interesting in part, because I would say as a science and technology studies scholar, that it’s a technological fix, right? And that’s never enough, you have to have a sociocultural system, a material and social way of delivering technologies, in order for it to work.

We have a pandemic that has increased social isolation, meanwhile you have a harm reduction movement that says never use alone. Because you can’t administer Naloxone to yourself, if you’re overdosing.

In the U.S., there was a week in March when there was twice the number of overdose deaths as there were COVID related deaths. That’s because people can’t help each other out.

I think we have to think hard about the infuse the principles of mutual aid and harm reduction in the face of existential crises. Harm reduction is a global social movement. People know one another all over the world. Drug using is a global social movement, drug users recognize one another and have trust with one another.

It comes down to the socio-material organization of trust. Who are you going to trust in this moment?

“If we could have produced a worse problem, I don’t know how we could have done it.”

I think that at the moment, it’s very important to listen to the harm reduction movement, listen to how communities come together. Ask what technologies of solidarity are. Naloxone, is one amongst many. Naloxone was simply one that has allowed me to tell a story about the way in which it came to be central to a socio-political movement.

SK: The last thing I’m going to ask you is, what do you say to someone who’s listening and doesn’t think it’s hugely important? Maybe they don’t think they have any direct relationships with anyone who uses drugs or they think that these kinds of policies aren’t where government money should be spent.

NC: The war on drugs has failed, even if you consider it on its own terms. We’ve got more, better quality, and lower priced heroin that we did when it started. It’s also clear that mass incarceration is an ineffective and expensive way to do social policy.

As well as the market dynamics of illicit economies, the war on drugs, and mass incarceration, you would also have to look at the pharmaceutical industry. As soon as we tried to regulate physicians to stop prescribing them, and required pharmacies to report how much they were selling, more and more people turned to the illicit market. The markets are clearly interlinked. They are clearly functioning together. We can’t really address the dynamics in one, without addressing the effects of the other.

If we could have produced a worse problem, I don’t know how we could have done it. Prior to the pandemic, it accounted for a very large share of completely preventable deaths. In the U.S., its people in their 40s and 50s, who are dying from overdose, prior to the pandemic. It seems to me, that anyone who wanted to claim that drug policy and the war on drugs has been successful, would really have to be evaluated in terms of their sanity.

People would have to agree that we should do something different. Harm reduction was a movement of people who said, we agree, let’s do something different. They took concrete steps to improve the situation. Scale it up. And attempted to build harm reduction infrastructure. They’ve made incredible progress without full support and without full funding. They would be able to do even more if they had more support.

SK: Thank you so much for chatting to me today. I’m really excited to share this episode with people.

Sam Kelly is the host of the MIT Press podcast and a member of the Press’s publicity and marketing team.

Nancy D. Campbell is Professor and Head of the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. She is the author of several books, most recently “OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose.”