Podcast: The Art, Craft, and History of Translation

“For some, translation is the poor cousin of literature, a necessary evil if not an outright travesty,” writes translator Mark Polizzotti in his bracing manifesto “Sympathy for the Traitor.” “For others, it is the royal road to cross-cultural understanding and literary enrichment.”

In this episode of the MIT Press podcast, podcaster Chris Gondek talks to Polizzotti about the long, rich history of translation, the real-life consequences of mistranslation, and the sometimes hilarious shortcomings of machine translation. Polizzotti is the author of several books, including “Sympathy for the Traitor,” “Bob Dylan’s Highway 61 Revisited,” and “Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton,” and the translator of works by, among other writers, Gustave Flaubert, Paul Virilio, and Nobel Prize winner Patrick Modiano.

A stream and transcript of the podcast can be found below.

Chris Gondek: Hello and welcome to the MIT Press Podcast. I’m your host, Chris Gondek. Today I speak with Mark Polizzotti about his new book, “Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto.” Mark Polizzotti has translated more than 50 books, including works by Patrick Mariano, Gustave Flaubert, Raymond Roussel, Marguerite Duras and Paul Virilio. Publisher and Editor-in-Chief at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, he’s also the author of “Revolution of the Mind: The Life of André Breton” and other books. Mark, thanks so much for taking time to talk to the MIT Press Podcast today.

Mark Polizzotti: Thanks so much for having me, Chris.

Chris Gondek: Now, your new book looks at the history of translation both as a subject and as a personal reflection on your time as a professional translator. It also helps readers learn how to appreciate the translator’s art. These three topics all intertwine, but was there one that motivated you to start this project?

Mark Polizzotti: Yes. In fact, there were several. One of them was that I, like a number of translators, have long felt that the work of translation and what a translator does is not very clearly understood by even people who read translations. In other words, it often seems to a number of even sophisticated readers that translation is largely a process of finding a word that is the equivalent of the foreign word and just simply coming up with the best equivalent.

Whereas, in fact, it’s much more complex than that and to my way of thinking, it really does result in the creation of a new work of art based on the other. That’s one. The other is that in academia in particular, in the discipline called translations studies, I’ve often been made rather impatient by a discourse that seems to me very far removed from what I consider to be the essentials of the art and craft of translation.

That has very little to do with the practice of translation and that in fact even oftentimes seems to go as far as almost denying the validity or the possibility of translation. So, this book was meant to be a discussion, a reframing and to some extent a corrective.

Chris Gondek: So, in those works in translation studies that are beginning to question that, I have to ask it, because I imagine listeners are asking this themselves, are the people doing this active translators or are they one step to moving to academia and studying translation but not really translators themselves?

I guess, are people that are in your boat as a professional translator, are they also … It would seem odd that they would be questioning the fact that translation could even happen. I’m just trying to get a sense of if this is a situation in which academics who aren’t doing it are coming to conclusions about what it is.

Mark Polizzotti: That’s actually a great question. It’s a little bit of the old joke “If you can’t do, teach.” That would be unfair. These people are very intelligent. They’ve thought a lot about this. There are some extremely thoughtful pieces, but to answer your question, most of them are not practicing translators, and the ones who are seem to be translating according to a philosophical or theoretical agenda that has very little to do with trying to create the best work in the English out of foreign work.

Chris Gondek: I mentioned in the first question that this is a book about the history of translation, and where people who maybe really haven’t thought about it … To me when I first thought about it, well obviously the first translations that came to my mind were the Romans who translated the Greeks during the Empire; but you also point out that early translations of the Bible, moving from Greek and Hebrew to Latin, were a little challenging. It seems that the Bible is one of the central texts in this question of translation, and I know that from other shows I’ve done for publishers that that translation into English, the King James Bible, was not only a very important translation that occurred but for some people a really dangerous translation. Is it fair to say that when we look at the history of translation, particularly into English, that the King James Bible kind of stands as the lodestone for how translation … Really where the debate started in English?

Mark Polizzotti: I don’t know that it’s quite where the debate started, although you’re absolutely right. It has been a lodestone and it’s been one of the most influential translations of all time. The number of phrases and words that have come into the English language through the King James Bible is just phenomenal. You can look it up online; I won’t rehearse them here. But even I was surprised at how many common phrases originate with the translators of the King James Bible.

In fact, Bible translation and the debates about Bible translation go back much farther than that; really back to Saint Jerome, who was the translator of course of the Vulgate, and he was the one who initially translated the Bible from the Hebrew into Latin and rather than using the Greek text, the Septuagint, which had been the authorized text and the standard text for quite some time. This was considered to be the definitive text because according to legend at least, the Septuagint had been translated by 70 scholars in 70 days, completely independently, and all of them came up with exactly the same text and therefore this is proof that they were inspired by God. It had incredible authority, and Jerome was really the first one to question the authority of this text on the basis of the fact that it simply didn’t read very well. Even though it had the spiritual imprimatur of the Church, it really wasn’t very fun to read.

Jerome approached this really as a poet in saying that there are in the original beauties of language that this translation simply does not convey, so I’m going to go back to the source and I’m going to translate it into Latin, which was the vernacular of the time, and make it more accessible to the common person, to the common worshiper, but also make it a text that one actually wants to engage with.

Well, that all sounds perfectly logical and reasonable. The problem was that it ran afoul of the orthodoxy, and in particular the future Saint Augustine, who was the monitor of all things holy and/or at least liturgical, and he was completely incensed about this because he thought that if he were to have two different translations you were going to end up having a schism in the Church, and in fact this is something that happened.

The Vulgate of course eventually superseded the Septuagint. It became the authoritative text, and the centuries later, around the 16th century, you have Martin Luther and you have William Tyndale, and these are another attempt to take the Bible and to turn it into a language that is accessible to the common person rather than the sort of text for the happy few. Happy few, therefore regulated by the clergy, therefore an authority that can tell you what you should or shouldn’t think of what the Word of God says. This of course, again, was very controversial with the Church because their authority was being undermined, they felt, and sometimes even directly. Tyndale in his introduction to his translation of the New Testament goes as far as to call the clerics malicious and wily hypocrites, so you can imagine how well that played. He was in fact executed because of this.

The irony is that in the following century, not very long after, Tyndale is executed at the beginning of the 16th century. At the very beginning of the 17th, you have King James, who commissions this new translation which is specifically supposed to reproduce the beauties of the language, and not only reproduce them but in fact invented quite a few that are still part of our language, English, today. The intent was in fact to do exactly what Tyndale had been executed for and that Luther had been censured for in the previous century, which was to bring the Bible to the common worshiper.

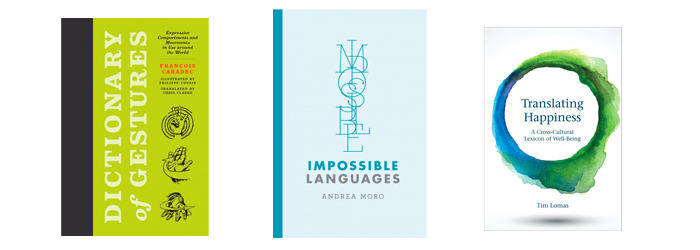

Recommended Books:

- Dictionary of Gestures | An illustrated guide to more than 850 gestures and their meanings around the world, from a nod of the head to a click of the heels.

- Impossible Languages | An investigation into the possibility of impossible languages, searching for the indelible “fingerprint” of human language.

- Translating Happiness | How embracing untranslatable terms for well-being — from the Finnish sisu to the Yiddish mensch — can enrich our emotional understanding and experience.

Chris Gondek: Listening to that question, it made me think about a work that, at least to my knowledge, I can imagine has been an issue for translators, and that’s the Quran. In the book, you talk about an issue of mistranslation when it came to Salmon Rushdie’s “The Satanic Verses,” which again, a question of a translation that has real-world consequences beyond just literary discussion.

Mark Polizzotti: Absolutely. Translation I think some people tend to think of as the province of word nerds, but in fact translation can have very far-reaching consequences, and in the book I talk about several mistranslations, one of them indeed being the translation into Arabic of “The Satanic Verses.” What happened there was that the translator by translating the phrase literally in fact not only did a disservice to the text but did a disservice to Rushdie, who was then put under fatwa and had to go into hiding, and was put under a death threat.

What happened was that the so-called Satanic verse that Rushdie is referring to in the title is in fact a part of Quranic lore and it refers to several excised verses of the Quran that Mohammed understands have been dictated by Satan and are therefore removed.

Now, in Arabic those are referred to as … the bird verses, not the Satanic verses. By using the English term, which was in fact a term made up by English-language orientalists in the 19th century … By using that term and translating it directly into Arabic, what the translator was essentially conveying was that Rushdie was saying that the entire Quran had been dictated by Satan, and of course that’s not at all what that title meant. But because of that, it was interpreted as a great blasphemy, and Rushdie was condemned and so on and so forth. That’s one instance.

Another one is World War II, where there’s a good indication that when the Emperor of Japan was asked to surrender right before the end of the war, instead of saying yes or no when a bunch of journalists asked him, “What are you going to do,” he said essentially “I need a moment to think about it. Let’s reflect.” Well, the word for “Let’s reflect” in Japanese, if taken out of context can also basically mean “I’m ignoring you,” and that’s how it got back to Truman, and several days later the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. These questions of translation can have enormous consequences.

Chris Gondek: Now, some people might be listening to this on iPod, iPad, their computer, and thinking to themselves, “You know what? This is all really great to talk about as far as things that happened in translation in the past, but all I gotta do is open up a browser and type things into Google Translate, and boom I get a translation.” Maybe they’re thinking, “Well, this is a question ‘Are the days of professional translator numbered because artificial intelligence and machine translation are gonna be able to do it all?'” This is a topic that you addressed in the book. Could you tell me your thoughts?

Mark Polizzotti: Absolutely. It depends on what you mean by translation. If it’s simply a matter of translating information, Google is great. I’ve used it myself. It’s wonderful if you happen to be in a foreign country where you don’t speak the language and you need to go into a pharmacy and ask for aspirin. You look it up on your phone, even if you can’t pronounce it you show the pharmacist, you get your aspirin. I’m all for it.

When it comes to literature I don’t believe that that is going to happen, at least not in any time in the near future, and I’ll tell you why. Again, translation is not about information. Translation is not about word equivalences. Translation is about understanding the deep structure and the underpinnings of what is going on in literary texts, what the author meant to do, how the author did it, how that can be conveyed, what that means in the author’s original culture, what the resonances are, what the effect on the reader is; understanding all of that, incorporating all of that into yourself as the translator and co-writer, and then trying to figure out ways of recreating and re-representing that in another language, another culture, sometimes another time period. With all those differences you still nonetheless need to make a text that on the other hand represents the effect on the reader the way the original text affected the original reader, and yet at the same time can speak to a reader today in a different culture, a different language, a different context and a different time period.

That takes a lot of choice, it takes a lot of subjectivity, it takes a certain amount of talent, and it’s something that to this day, even with the advances in AI and with the advances in computer technology, we are nowhere close to being able to have, and even the people who are proponents of machine translation, and I’m talking about not at the beginning of it but now, would tell you that this is not something that machine translation is set up to do.

Machine translation is great for certain kinds of standardized documents; it’s great for set phrases; it’s great for information; it’s great for vocabulary, and even then you have to be careful; but it is not made for translating art. It is not made for translating literature. The idea that you can do that I wouldn’t say is dangerous but I think it’s a little bit dispiriting because what that suggests is a view of translation that again is a kind of a rote dictionary work whereas in fact it’s a much, much more creative, much, much more engaged process than that.

The other thing to keep in mind is that Google is not a dictionary. It’s a search engine. You can take a phrase from Proust and you can put it into Google and you see what it comes up with. Well, the thing is that sometimes you will get a perfectly reasonable translation. Sometimes you will get a translation that is pretty much word for word what the published English translation by a translator is, and sometimes you’ll get the kind of gibberish that you could get if you were reading a badly translated instruction manual in a foreign appliance.

The reason is that Google is basically just looking for clues. It’s looking for what’s already out there. Something like Proust, the translation of Proust by CK Scott Moncrieff, has at least been entered into somebody’s database or is available online. Google is smart enough to recognize that the opening phrases of this work in French correspond to the opening phrases of that work in English, and it’ll find it and it’ll bring it out to you. But try doing it with something that’s a little bit more obscure and you end up with a phrase that is completely off the mark.

Because that’s just not how Google works. It doesn’t have the creative thinking. All it can do is go out and find existing equivalents that it thinks are the ones that match, and to me, one of the great examples of this is an attempt some years ago to take a phrase, “The spirit is willing but the flesh is weak,” and they fed it into a computer in Russia and basically asked it to translate it and it came back with a phrase that I’m sure to its circuits seemed perfectly logical, which is “The vodka is good but the meat is rotten.” Completely different reading of what that phrase meant.

I think there was another one, a similar example. Somebody in Japan took the phrase “Out of sight; out of mind,” and it came back with the equivalent of, “Confined to an insane asylum.”

Chris Gondek: By the way, “The vodka’s strong but the meat is rotten” is now the official way we use that phrase in our house … Tell my wife that! I will give you an example for the last question from my own personal history, and you can help decide whether I want to go back and do this. Back when I was an undergraduate I was taking a class on English literature from, I wanna say 1680 to 1750, and for some reason … Professor Bell, you’re out there. I love the class … If he’s listening to me. But we had to read Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad or part of it, and I couldn’t get through it. I thought Alexander Pope was very clever, I enjoyed “The Rape of the Lock,” but when I read the Iliad my eyes just crossed. I thought, “Oh man. I can’t get through this.” Now, I like classical language and I like classical literature. I read Fagles’ translation of the Iliad when it came out, and I was just blown away. I was like, “This is amazing.” I like the Iliad. Should I go back and read Pope? If I do, do you have any suggestions for me on how I might be able to appreciate Alexander Pope? It’s one of the things where sometimes when you have a work of art you just like one person’s translation and you just don’t like another person’s translation.

Mark Polizzotti: Well, that’s absolutely true, and of course when there are numerous translations to choose from … Look, I’m not going to say that a translation is better than another. I think that having a multiplicity of choices I think is a great thing. If it were up to me and someone were to ask, I’d say go back and read all of them. Of course, with the Iliad you could really have your work cut out for you. The fact is if you were to go back now and read Pope’s translation, I would say basically you do it because you want to go back and read, not because you want to read Homer. If you want to read Homer you are much better off with Fagles or some of the others who have translated it more recently.

The thing to remember too is that translations, even more than the original work, are perishable items. They are dependent on their time, they’re dependent on the culture in which they were made. There is a certain immutability about the original because it has that particular authority. We’ll still try to read Shakespeare in his original language, but the Shakespeare that was translated more or less contemporaneously into other languages would seem completely silly today if the translator were trying to translate Shakespeare that way.

Or to take the opposite tack, Montaigne was translated in more or less his day by John Florio. I’ve read those translations. They are very elegant and they’re very interesting, but they sound awfully florid and they sound very much of the time. There are much better translations to my more modern ear of Montaigne that have been done closer to my own time, and I enjoy them more because they speak to me in the idiom that I understand and the idiom that I’m used to, just as Montaigne of his time spoke to his reader of the time that he was writing it.

I think that translations do get superseded. One day Fagles will seem really old fashioned and your children or their children will say, “God. Who can go back and read this? This sounds so fusty and fuddy-duddy. Let me read Zorc’s because it sounds much more like something that I understand.” That is one of the wonderful things about translation. There is no definitive one. There are some that are better than others, for sure, but they are going to be superseded.

In a way, this also brings back a question that you asked earlier about the question of fidelity, and how much liberty should one take or how much should one try to adhere to the “original”, whatever that means. That of course is one of the great debates from the very beginning, is “Well, part of it depends on what it is that you’re trying to do.” If for example you are translating the Bible, we have multiple examples, and I cited a few of them before where somebody taking liberties can get himself into really hot water, because that was supposed to be the Word of God and you didn’t mess around with it. But if you’re translating literature, secular literature, and if your aim is to try to create an effect that is in some way equivalent or in some way comparable, let’s say, to the effect that the original author had on his or her audience, then you do need to make certain adaptations. You do need to make certain … I wouldn’t call them concessions. You need to be creative at certain times, and you need to do it very sensitively and that’s where the art comes in.

Not everyone can do it. I think it’s a matter of feeling the text. Even very good translators should not translate every text. Sometimes you really understand what’s going on and you feel that you get it and you can convey it. I’ve had plenty of cases where I’ve read a text that I have absolute respect for but I’ve had to turn the job down because I just know that I’m not going to be able to do the job on this book that I would expect of myself to do. I don’t have the feel for it. That’s an open-ended question, but I hope that’s the beginning of an answer to it.

Chris Gondek: Mark Polizzotti, the author of Sympathy for the Traitor: A Translation Manifesto. Thanks for being on the MIT Press podcast today.

Mark Polizzotti: Thanks very much, Chris. I enjoyed it.