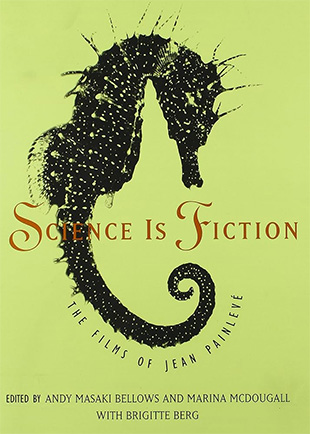

Science Is Fiction: Inside the Wondrous Early Films of Jean Painlevé

The French filmmaker Jean Painlevé (1902–1989) was one of the first people to plunge underwater with a camera and bring the subaquatic world to the screen. His films, like his life, eluded easy categorization: While many artists viewed science as a specialized domain restricted to practitioners, Painlevé “kept one foot planted in the biology laboratory, the other in murky waters teeming with aquatic life,” says curator Marina McDougall, who initiated the first United States retrospective of the filmmaker’s work in 1991. Fittingly, Surrealist contemporaries such as Antonin Artaud, Man Ray, Luis Buñuel, and Jean Vigo are among those who admired his work.

In a lifetime spanning nearly the history of cinema itself, Painlevé made over 200 short films, including “The Seahorse,” “Freshwater Assassins,” “The Vampire,” and the eerily beautiful “The Love Life of the Octopus.” When asked how he achieved the chilling effect of the narrator’s voice in the latter, notes Brigitte Berg in the essay from which the following text is excerpted, Painlevé offered this playful explanation: ‘He was an old man who, out of vanity, refused to wear glasses. He was therefore obliged to stick his face right up against the script, close to the microphone, where one could hear his emphysema.’”

It’s this kind of intimate detail that makes Berg’s biographical essay, which can be read in its entirety in the volume “Science is Fiction: The Films of Jean Painlevé,” so compelling. Drawing on unpublished archival documents and photographs from her time collaborating with Painlevé in his final years, Berg offers a rare glimpse into the life and career of an avant-garde filmmaker who brought the hidden wonders of nature to the screen with unsettling beauty, and who mingled and merged the seemingly separate worlds of science and art like no one before or since.

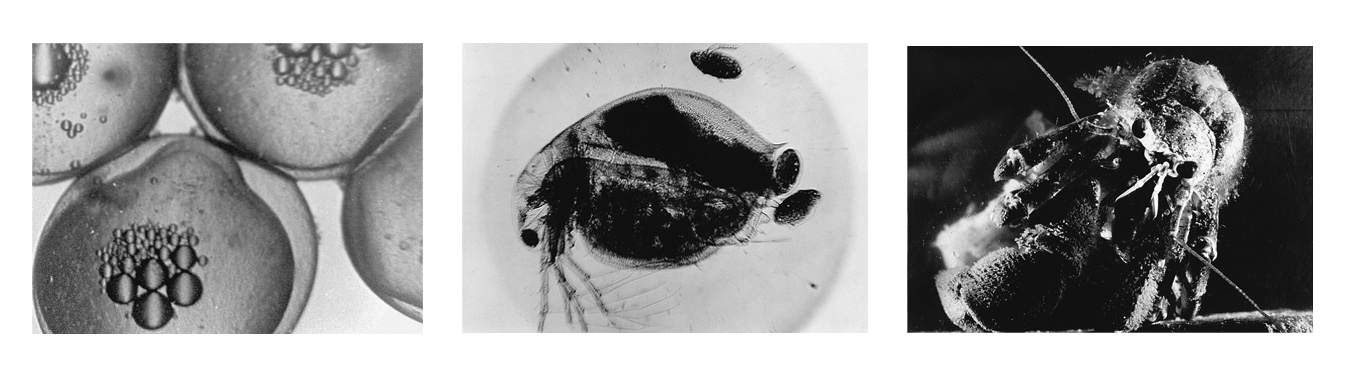

Early Films: Stickleback Eggs and Octopi

“The Stickleback’s Egg” screened before an audience of scientists at the Académie des sciences in 1928 where it was met with intense skepticism, if not outrage. One scientist, infuriated, stormed out, declaring: “Cinema is not to be taken seriously!”

This was not the first time film had entered the illustrious academy: In 1910, the French science filmmaker Dr. Jean Comandon had presented a film about the syphilis spirochete to a similar reaction. The prevailing attitude among scientists and academics was that cinema was frivolous, or, as the author Georges Duhamel put it, “entertainment for the ignorant.”

One scientist, infuriated, stormed out, declaring: “Cinema is not to be taken seriously!”

The reaction to Painlevé’s film, however, only solidified his resolve. To promote the use of film in science, Painlevé cofounded the Association for Photographic and Cinematic Documentation in the Sciences in 1930 with Michel Servanne, head of the Musée Pédagogique, and Dr. Charles Claoué, a pioneer of plastic surgery who would later become famous for the “Claoué nose,” a pert little pug sported by French celebrities such as actress Juliette Greco. Throughout the 1930s, the association held international conferences, screening such science films as “New Research on Amoebas,” “Operation on the Upper Palate,” “The Play of Productive Children,” and “Lymph Glands of the Frog.”

Scientists, though, were not the only ones skeptical of the legitimacy of science film. “How can we be sure that what we see on the screen is documentary truth?” asked a journalist. “When an actor is in front of the camera, he transforms himself, he modifies his behavior. So, are we sure that the stickleback’s egg itself is not disturbed, modified, or distorted by the camera and the lights?”

Amid this atmosphere of distrust, Painlevé would later recount how he averted a potential disaster. While editing the original copy of “The Stickleback’s Egg,” Painlevé accidentally ignited the film with a cigarette. He hastily assembled a second copy for the screening at the academy but inadvertently put one of the sequences in backward. At the screening, Painlevé was not the only one to notice a perplexing phenomenon. Several specialists approached him asking to see the film again. Given the late hour, Painlevé was able to convince them to return the next day to view it. He immediately rushed home and quickly turned the sequence back around. The specialists never again saw the strange phenomenon of the heart rejecting the corpuscles instead of attracting them. Realizing the graveness of this error, Painlevé added, “Had I attributed this mistake to careless editing, and because cinema was already considered a sham, I think films would have been forbidden in labs and universities.”

Painlevé’s precarious position within the scientific community would continue throughout his career. The French avant-garde, however, embraced his work from the very beginning. When Painlevé’s study of skeleton shrimps and sea spiders, “Caprella and Pantopoda,” was screened in 1930 at the newly opened Les Miracles theater, Fernand Léger called it the most beautiful ballet he had ever seen, and Marc Chagall praised its “incomparable plastic wealth,” calling it “genuine art, without fuss.” Man Ray borrowed footage of starfish from Painlevé to use in his own film “L’Etoile de mer,” and Georges Bataille published Painlevé’s stills of crustaceans in his review Documents.

Following “The Stickleback’s Egg,” Painlevé began an intensely productive period, making a series of silent shorts on animal behavior for the general public. “The Octopus,” “The Daphnia,” and “The Sea Urchin” were shown at such theaters as the Studio des Ursulines and the Studio Diamant before the evening’s feature. Eager for the feature, there were some in the audience who would boo; but there were others who were enthusiastic such as noted critic Elie Faure: “The science films of Jean Painlevé . . . in showing the dancing and glittering life of a mosquito, bring to mind the enchantment of Shakespeare and allow one to glimpse the exhilaration of the mathematician lost in the silent music of infinitesimal calculations.”

For his 1929 film “The Hermit Crab,” Painlevé for the first time added a musical accompaniment. Through Robert Lyon, the owner of the prestigious concert venue Salle Pleyel, Painlevé met the composer Maurice Jaubert who provided a musical score for the film. Jaubert chose a composition by Vincenzo Bellini. Painlevé would later admit that he would have preferred a score written specifically for the film.

When Jean Vigo arrived in Paris in 1932 to shoot “Zero de conduit” — which would later be banned by the French Board of Censorship, presumably for its harsh portrayal of French bourgeois institutions — Painlevé introduced Vigo to Jaubert, who then composed the score for Vigo’s film. For one of the scenes, Jaubert recorded the music normally, then played it backward, achieving a dreamlike effect.

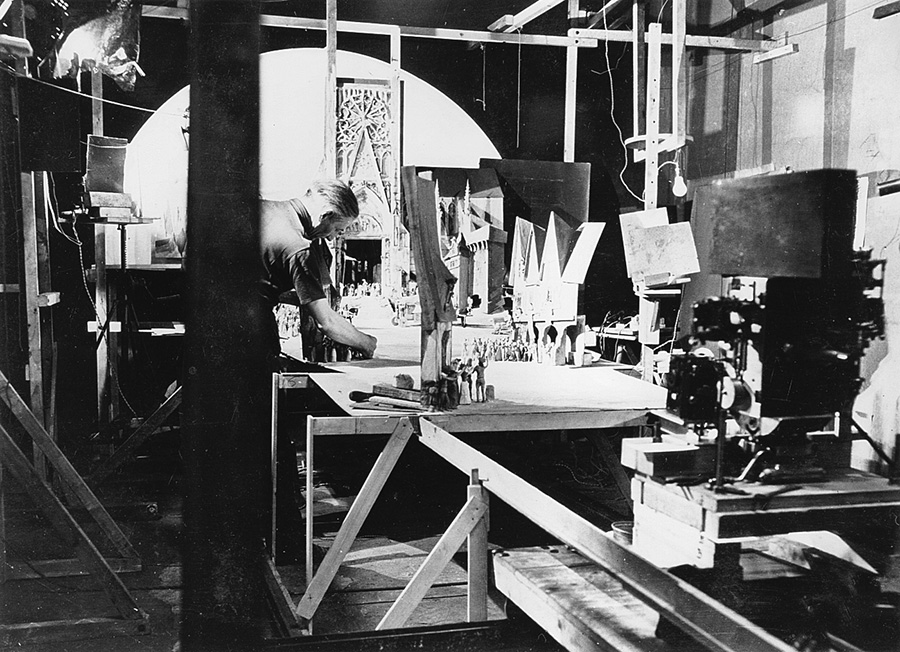

With the use of a special camera, each frame of “Bluebeard” was shot three times using three different color filters. It would take three painstaking years to finish.

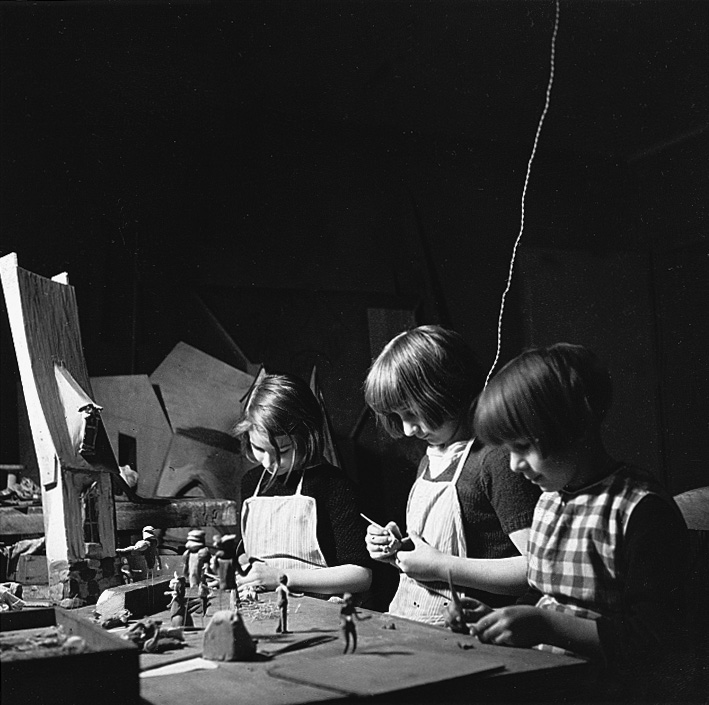

Entranced with the result and pleased by his show of inventiveness, Painlevé asked Jaubert to compose an original score around which he would produce a film. Thus, “Bluebeard” was conceived. From Jaubert’s 13-minute opera buffa, or comic opera, based on the tale of Bluebeard and his murdered wives, sculptor René Bertrand, aided by his wife and three young children, created hundreds of figurines out of clay that were then animated and filmed. With the use of a special camera — adapted by André Raymond from an old Pathé — each frame was shot three times using three different color filters and then developed according to the Gasparcolor method. “Bluebeard” would take three painstaking years to finish.

In 1938, at the first public screening of “Bluebeard,” Painlevé began his presentation by paying homage to Emile Cohl and Georges Méliès, inventors of animated film, who had both died that same year, largely forgotten.

Painlevé would often champion the work of others, paying particular attention to films that faced government censorship. One such film was Sergei Eisenstein’s “Battleship Potemkin,” which chronicled the unsuccessful 1905 revolution against the Russian tsar. Viewed as Communist propaganda, the film was deemed “subversive” by European officials and censored. Thus, when Painlevé and his friend, the documentary filmmaker Joris Ivens, screened it in Amsterdam, they posted sentries at the theater door to watch for police. When the police did arrive, Painlevé and Ivens quickly stopped the projection, grabbed the film reels, and, with the audience in tow, scurried to another theater. There, too, the screening was interrupted by police. So the group moved again. In the course of one evening, the group moved six times, but in the end “Battleship Potemkin” was shown in its entirety.

When Eisenstein himself came to Paris in 1930, Painlevé asked his father for help with the officials. Paul Painlevé ordered the head of the French police to leave the filmmaker alone. During the visit, Painlevé took Eisenstein on a grand tour of Paris: to Palais Royal square, to a café where poet Alfred de Musset reputedly sipped absinthe, to the Comédie-Française to ogle at the lavishly dressed crowd. “He enjoyed this classic bourgeois scene,” Painlevé would later recall. “I also took him to the Cigale theater to see an exceptional American film ‘Red Christmas.’ Afterward, we wandered around the Clichy fairgrounds . . . and had our photo taken in a mock airplane.” Painlevé also arranged for Eisenstein to travel secretly to Switzerland: “I had him hidden in a van of dirty laundry. He wanted to see Valeska Gert, a Swiss actress he adored.” When Eisenstein left Europe for the United States and Mexico, he wrote a series of postcards to Painlevé in which he chronicled his travels.

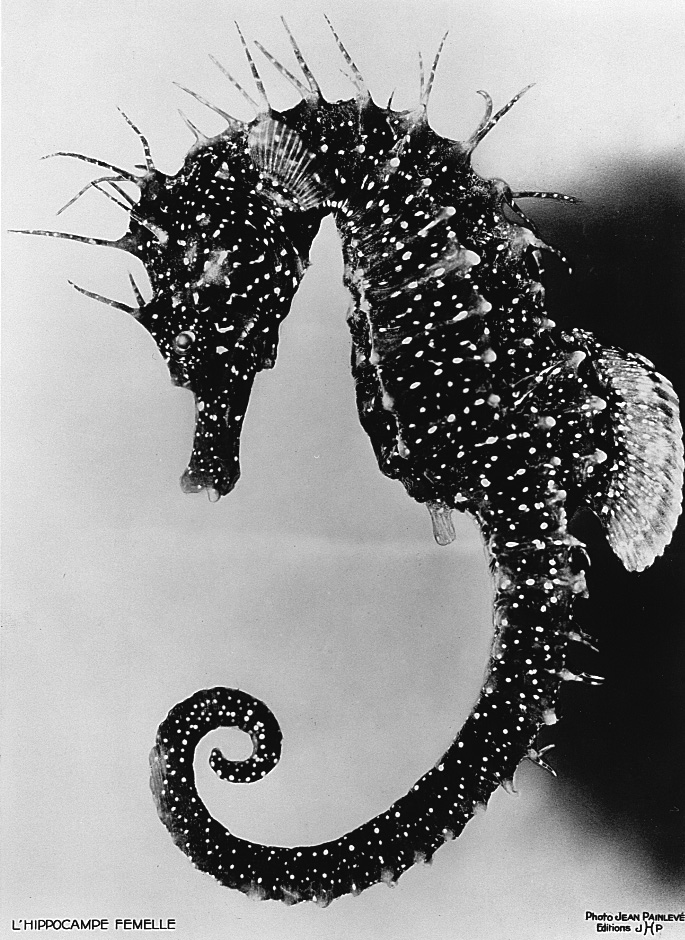

The Seahorse

In the early 1930s, when Painlevé set out to make one of the first films ever to use footage shot underwater, he chose as its subject the seahorse — a species with unusual, and to Painlevé, commendable sex roles: Whereas it is the female seahorse who produces the eggs, it is the male who gives birth to them. “The seahorse,” he would later write, “was for me a splendid way of promoting the kindness and virtue of the father while at the same time underlining the necessity of the mother. In other words, I wanted to re-establish the balance between male and female.”

To film underwater, Painlevé enclosed a Sept camera — given to him by Charles David, the head of production at the Pathé-Natan studio — in a specially designed waterproof box fitted with a glass plate for the camera’s lens to peek through. The filming, which took place in the Bay of Arcachon, was arduous. The camera could hold only a few seconds of films, causing Painlevé to return to the surface continually to reload. Moreover, the diving equipment he used was crude, so his movements were limited. Essentially tethered to a boat, his breathing apparatus was connected, by a 10-meter-long hose, to a manually operated air pump located above water. Painlevé would later recall the difficulties: “The goggles were pressing against my eyes, which, at a given depth, triggers an acceleration of the heart by oculocardiac reflex. But what bothered me most was that at one point I was no longer getting any air. I rose hurriedly to the surface only to find the two seamen quarreling over the pace at which the wheel should be turned.”

The filming continued in Paris in a basement studio outfitted with immense seawater aquariums. There, Painlevé and André Raymond set up a camera and waited patiently for one of the seahorses to give birth. At first Painlevé manned the camera, but after several days of no sleep, he asked Raymond to fill in for a few hours. Raymond fell asleep. So Painlevé took over again — but not before installing a device on the visor of his hat that would emit a small electrical shock if, from fatigue, his head should nod onto the camera. Painlevé was thus able to film the birth.

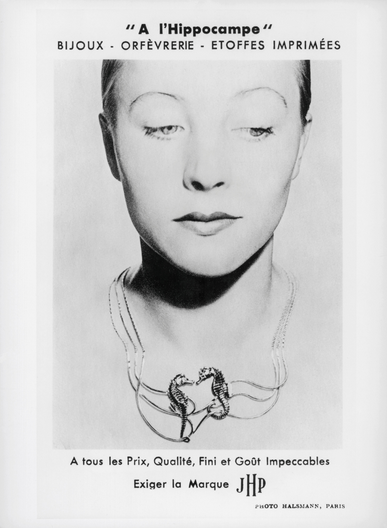

Financed in part by a personal loan from Bernard Natan, who then distributed it through the Pathé-Consortium, “The Seahorse” was a popular success — the first and only of Painlevé’s films to break even. Indeed, so popular was the film that Painlevé launched a line of seahorse jewelry: gilded bracelets, necklaces, pins, and earrings that were designed by Geneviève Hamon, sold under the label “JHP” (for Jean Hippocampe Painlevé) and displayed in chic boutiques alongside aquariums filled with live seahorses. Promotional photographs were shot by Philippe Halsman, the Lithuanian-born photographer whose work is collected today in such books as “Dali’s Moustache” and “The Jump Book.”

The jewelry venture proved to be very profitable — but Painlevé never saw any of the money. Uninterested in running the business, he had taken on a partner, Clément Nauny, to manage the manufacturing end of the operation. At the end of the war, Nauny made off with the profits and absconded to Monaco where he was never heard from again.

Brigitte Berg is the director of Les Documents Cinématographiques in Paris, an independent archive founded by Jean Painlevé in 1930. This article is excerpted from her essay in the book “Science is Fiction: The Films of Jean Painlevé.”