In Conversation With Urban Epidemiologist Tolullah Oni

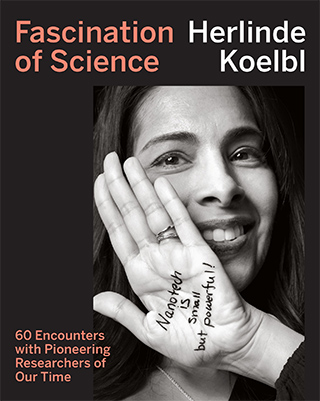

What makes a brilliant scientist? Who are the people behind the greatest discoveries of our time? Connecting art and science, photographer Herlinde Koelbl seeks the answers in her book “Fascination of Science,” an indelible collection of portraits of and interviews with 60 pioneering scientists of the 21st century. Koelbl’s approach is intimate and accessible, and her highly personal interviews with her subjects reveal the forces (as well as the personal quirks) that motivate the scientists’ work.

“I wanted to know how they think and with what insights they influence our lives, our future,” writes Koelbl in the book’s preface. “To this end, I traveled halfway around the world to ‘research’ these top scientists and to pass on their fascinating scientific results and life experiences — in other words, to bring science to life.”

Throughout August, we’re featuring one interview from the book each week. This week, Koelbl chats with Tolullah “Tolu” Oni, an urban epidemiologist based at the Medical Research Council Epidemiology Unit at the University of Cambridge.

Other interviews in the Fascination of Science series include:

AUGUST 1st: Frances Arnold / A pioneer in the field of “directed evolution,” a genetic engineering acceleration of random mutations, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2018. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 7th: Paul Nurse / Biologist, geneticist, and Director of the Francis Crick Institute, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2001 for his discoveries concerning the regulation of the cell cycle. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 21st: Françoise Barré-Sinoussi / Virologist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2008 for her contributions to HIV/AIDS research and as a co-discoverer of HIV. Read the discussion here.

—The Editors

You were born in Lagos, Nigeria. How did you manage to make it big in the West?

Well, I would argue that I’m still making it big. Fundamentally, I think my parents instilled a sense of drive and ambition in my siblings and me from the word go. As a result, we’ve been blessed with a sense of purpose and a feeling of unlimited potential — the belief that we can achieve whatever we set out to do.

Your parents were clearly a positive influence on you. What were their jobs?

My father’s background was in food science and technology, and he worked for a multinational corporation. My mother was a French lecturer at the university. She shielded me from society’s sense of female inferiority and instead made me feel that there wasn’t any glass ceiling. I guess I was lucky in that respect, given the gender inequality a lot of women face today. With hindsight I can see that this was a deliberate action, and my upbringing was unusual, but at the time I thought anybody could do anything they wanted, regardless of whether they were a girl or a boy. I used to wait at the university for Mum to finish her lectures, and it never struck me as anything unusual — it was just what she did. And if she did it well — well, why shouldn’t I?

Were you one of the brightest and best at your school?

I’ve always been ambitious, and I strived to be one of the best. I tried hard and didn’t just rely on natural talent. I’m naturally competitive, so my siblings and I would compete to see who would be top of the class by the end of term. I was a mixture of just sheer stubborn ambition and drive, which made me a fighter.

“At the time I thought anybody could do anything they wanted, regardless of whether they were a girl or a boy.”

You say that you were ambitious. Can you remember your earliest ambition?

Yes, even as I child I knew that I wanted to be a doctor, as I wanted to do something that would positively impact other people’s lives. When I was about seven years old, I watched a documentary about open-heart surgery performed on a child, and I was fascinated by the heart — it just looked so alien. I decided then and there that I wanted to be a pediatric cardiologist, as I was really struck by this sick child who should be running around playing or at school. I realized, I could do something to help children, just like me. That’s what I want to do!

So, how long did you live in Lagos when you were growing up?

I stayed in Lagos until my mid-teens. My parents wanted me to be schooled in a globally competitive education system, so they sent me to a boarding school in Surrey, on the outskirts of London, to finish my schooling.

After school, I took medical studies at the University College of London, before completing an internship in medicine and surgery in Newcastle upon Tyne. Then I spent a year down under, working in internal medicine in intensive care in Sydney, Australia. When I returned to the UK, I worked in a London hospital, and I focused on infectious diseases.

I believe you were particularly interested in HIV medicine even at that early stage?

Yes, I grew interested in HIV following my bachelor’s degree in international health, which I completed after taking a year off during my medical studies. This fed my desire to understand the drivers of ill health — how factors outside the country impact something locally. It was a real wake-up call.

I wrote my thesis at Médicins Sans Frontières [Doctors Without Borders] about adherence to anti-retroviral treatment — namely, the treatment for HIV. It was the year 2000, and back then there was a (misguided) perception that people in poor countries couldn’t take HIV treatment, as they didn’t own a watch so they couldn’t know when to take their treatment. Médicins Sans Frontières wouldn’t accept this excuse and decided, “We’re going to start providing this treatment in low-income countries and show that this is possible.” They began pilot programs in various countries, including South Africa, where the government was still in denial about HIV, and they provided the first free treatments in a township called Khayelitsha, Cape Town.

And how were you personally involved in this project?

My job was to gather information from the nine pilot sites around the world, at intervals of six and 12 months after treatment had commenced. Unsurprisingly, the results showed overwhelmingly good adherence rates.

It was my first research project, and I found it an incredible experience. So, when I returned to London I thought, Right, this is what it’s all about. Instead of simply treating HIV, I wanted to find out, via research, how I could improve the mortality rates from HIV. But people in London had access to HIV treatments and were no longer dying, unlike in other places around the world.

So, you decided to go to South Africa, where they were in desperate need of HIV research?

Yes, I spoke to a professor and told him I wanted to carry out HIV research. He put me in touch with a contact in South Africa, and off I went. I thought I would go out there for 12 months, but I ended up staying for 11 years. It was fantastic.

You enjoyed great success in South Africa, but what hurdles did you face at the start?

Actually, personal doubt and fear of regret were my biggest hurdles. Medicine is such a conservative profession; you’re told after completing your training that your whole life is mapped out for you. But I’d jumped off the path mid-trajectory and was constantly told, “You’re wasting your career and you’re wasting your training.” I wasn’t certain it would all work out, and I was worried I would fall behind my colleagues.

I decided to ignore those feelings as best I could and I stayed to complete a research doctorate in epidemiology, a higher research degree.

What about working as a woman of color in South Africa? Did that present an additional hurdle?

That was an additional, complex dynamic I had to navigate. I grew up as one of a majority of black Africans in a country full of inequality, but not necessarily of racial inequality. South Africa has a majority of Black residents, but I encountered a huge amount of racial ignorance, with huge legacies of apartheid and structural racial inequalities.

How did you react to this form of prejudice?

Quite frankly, it was something I wasn’t equipped to deal with. I had a privileged background and received a good education. Sure, I was in a minority when I was studying in the UK, but that was never a problem; I still had access to good education and training. I loved Cape Town, but the city remained segregated in terms of where white and black people lived. There, I was a visible minority in a majority black country.

So, what did your patients think of you?

In the first few years, I did a lot of clinical work to accompany my research, and as I’d learned some of the local language, Xhosait, it took a while before my patients realized, “Oh, you’re not South African.”

I walked in with the attitude, “Yeah, I’m here to do stuff; I’m smart and I’m capable,” but before I even spoke, there was a sense of assumed inferiority because of the way I looked. When you engage in ways that challenge the notions that people have, then it confuses them. Basically, people didn’t know what to think.

Did you learn to live with their wrong assumptions?

Frankly, it was debilitating encountering that prejudice day in and day out. I used my inner strength to ignore it, and blocked it out by thinking You might feel this way but I don’t accept it and I’m not going to deplete my inner resources by trying to convince you you’re wrong and fight these daily battles.

“Before I even spoke, there was a sense of assumed inferiority because of the way I looked.”

What about gender inequality? Did you encounter sexism in regard to your professional abilities?

My saving grace was a professor I met while in Cape Town. He was on a mission to build and grow a cohort of academics, predominantly made up of women of color, who would take the lead in health science in South Africa. I immediately applied for a research position and got the job. I had very little experience, but I ended up running a large multisite study on tuberculosis. This professor relied on gut instinct and told me, “Even though you didn’t have experience, I just know you’re capable of the work.”

You ran your own lab. Did you enjoy managing a clinical research team?

A lot of research is about people — the people you’re investigating and the people you work with. So I had to quickly learn management and leadership skills, which I hadn’t studied in school. At first, I found it difficult because of cultural reasons; even though I’m extroverted, I always compartmentalized my work life and my home life. It was hard motivating my team, so after a few months a South African colleague explained it to me. “It’s people related. They don’t know anything about you.” I realized that I had to open up to them to build rapport. It was a big lesson for me.

What motivated you to work in the area of public health?

When you practice clinical medicine, you have a clear impact on particular individuals and that’s a rewarding feeling. But at the end of the day, you are just helping a limited number of persons. I turned toward public health, as I wanted to contribute to society as a whole and try to prevent more people from getting sick. Fundamentally, I wanted to increase the scale of my impact.

So, how did your work develop during your time in South Africa?

I initially went to South Africa to understand how HIV and tuberculosis interact and what factors drive the outcomes of people suffering from those two diseases. But then I started to notice how many people suffered from high blood pressure, diabetes, and obesity, so I looked at how these noncommunicable diseases interact. What became clear to me is that these are preventable conditions, driven by external factors such as nutrition and exercise, particularly in urban environments. In Africa, 62 percent of city dwellers live in slum conditions, where there is real potential for disease. I was working in a slum area, in an informal settlement. You tell a patient there that they need to eat better, and then you walk out of the hospital and see the reality, and you realize their choices are limited.

So, you wanted to look at the far bigger picture?

I’ve been looking at the bigger picture my entire life! Yes, so I decided to look further upstream — at the environmental exposures that were making people sick, such as food, housing, settlements. This wasn’t just about health care anymore. I decided to set up a research group called the Research Initiative for Cities Health and Equity (RICHE), and in fact I still lead the initiative today, trying not only to treat the illnesses but also to alter the conditions causing those diseases. We form partnerships with sectors that wouldn’t normally consider themselves responsible for public health matters, and we try to get them to understand the health implications of what they’re doing.

Africa is one of the continents with the fastest-growing population. What do you think can be done to improve public health?

Africa needs a good long-term strategy in terms of disease prevention and health creation. We mustn’t forget that disease is not inevitable; it’s preventable, especially among young people. Some people say we can’t afford to offer both health treatments and prevention; I say that we can’t afford not to. The cost of treatment is far higher than any amount of economic growth we could hope for.

Recently I’ve been focusing on young people, as the behaviors and preconditions for these diseases start when people become independent.

What should the West specifically be doing to help Africa?

If the West is serious about disease prevention and health creation, then it needs to pursue coherent policies and not be duplicitous. At the moment, one hand gives while the other hand takes away. The West has to stop acting so superior and begin to engage in meaningful, equitable partnerships, not paternalistic, “We know what’s best for you” approaches. Those never work out in the long term.

We’re all connected, and we need to start acting like we’re all part of the same ecosystem. We have to address the significant inequalities among countries and regions. Ultimately, doing so will bring us a collective increase in well-being.

How do you personally stay healthy?

That’s a long-term goal I struggle with on a daily basis. On the one hand, I find it difficult to turn down things that I’m interested in doing, and I tend to want to do everything. I strongly believe that I can have my cake and eat it, and I regularly try to do both. I go running a lot, and that’s how I maintain my mental well-being and my physical health. It’s how I create space for myself and clear my head.

What words would you use to describe yourself?

Energetic, stubborn, curious, a runner, optimistic.

So, what’s your advice to anyone interested in studying science?

There’s so much that we don’t know; science is a study of the unknown that allows you to contribute knowledge and understanding of the world. Sometimes in your pursuit of science you’re discouraged from forging new paths. My advice is this: Don’t fear the path less trodden; rather, choose it because that’s what science is all about. In terms of personal qualities and mindset, you need sheer persistence and the ability to remember your ultimate goal of why you do what you do.

Herlinde Koelbl is a German photographic artist, author, and documentary filmmaker. She has published more than a dozen photography books and has received numerous awards for her work, including the Dr. Erich Salomon Prize in 2001. You can learn more about her at www.herlindekoelbl.com. This interview is excerpted from her book “Fascination of Science.”