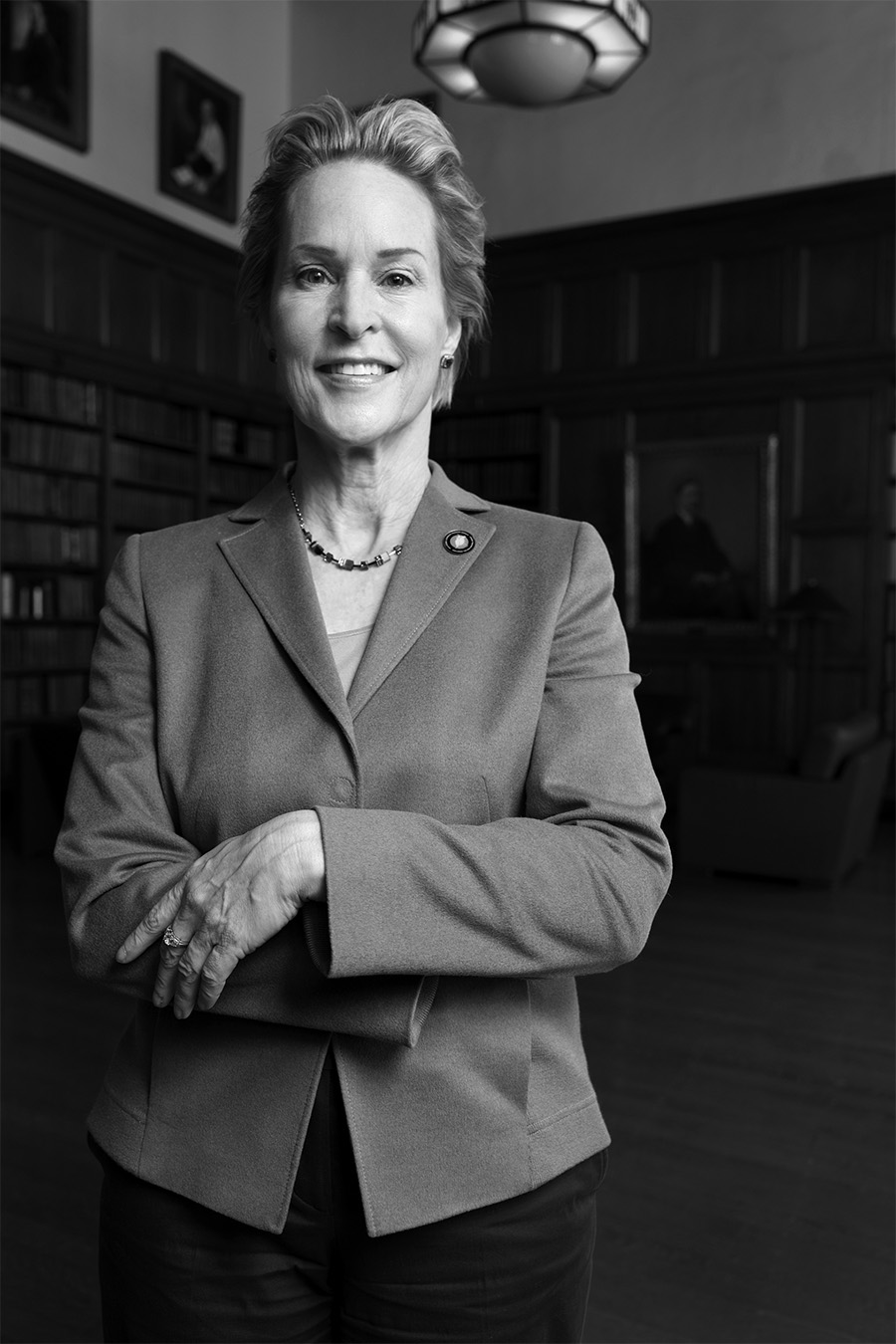

In Conversation With Nobel Laureate Frances Arnold

What makes a brilliant scientist? Who are the people behind the greatest discoveries of our time? Connecting art and science, photographer Herlinde Koelbl seeks the answers in her book “Fascination of Science,” an indelible collection of portraits of and interviews with 60 pioneering scientists of the 21st century. Koelbl’s approach is intimate and accessible, and her highly personal interviews with her subjects reveal the forces (as well as the personal quirks) that motivate the scientists’ work.

“I wanted to know how they think and with what insights they influence our lives, our future,” writes Koelbl in the book’s preface. “To this end, I traveled halfway around the world to ‘research’ these top scientists and to pass on their fascinating scientific results and life experiences — in other words, to bring science to life.”

Throughout August, we’re featuring one interview from the book each week. We begin with Koelbl’s discussion with Frances Arnold, a 2018 Nobel Prize winner and a pioneer in the field of “directed evolution,” a genetic engineering acceleration of random mutations.

Forthcoming interviews in the Fascination of Science series include:

AUGUST 7th: Paul Nurse / Biologist, geneticist, and Director of the Francis Crick Institute, who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2001 for his discoveries concerning the regulation of the cell cycle. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 14th: Tolullah Oni / Public Health Physician scientist and urban epidemiologist, who seeks to improve public health systems and address external influences on the health of urban populations. Read the discussion here.

AUGUST 21st: Françoise Barré-Sinoussi / Virologist and winner of the Nobel Prize for Medicine in 2008 for her contributions to HIV/AIDS research and as a co-discoverer of HIV. Read the discussion here.

—The Editors

Professor Arnold, how did growing up with four brothers and a father who was a nuclear physicist toughen you for the work in science?

I think I toughened my brothers. My family life early on was imbued with physics and mathematics, and I just assumed I would do something with that. It was friendly competition. I won, of course.

In the late 1960s, U.S. cities were burning: civil rights protests, antiwar protests. There was a whole generation of young people who didn’t believe what their parents were telling them. My family was torn, because my parents had four other children and thought I was a bad influence on them, with my protests and hitchhiking, and doing various other things they didn’t want my brothers to emulate. They told me I should either behave myself or I would have to leave. And I said, “I’m leaving!”

I wanted to find my own way in life. I was 15, but I knew I could make a living. I worked in a pizza parlor, I was a cocktail waitress, I drove a taxicab. And I found that independence was what I needed.

I love adventure. I was never afraid to do things or go places by myself, whether moving to Italy when I was 19, or later traveling through South America on local buses, staying at dollar-a-night hotels, and eating street food. (I got food poisoning any number of times.) I wanted to see the world. Curiosity and a sense of adventure drove me, but a lack of fear was also important.

How did you embark upon your career path?

I started off as a mechanical engineer because it had the fewest requirements at Princeton. For a long time, I didn’t know what I wanted to do. I had no intention of becoming a mechanical engineer, but that subject got me into a very good school. And I saw no reason to switch my major because I could take different courses that interested me, like Russian literature, Italian language, economics, art history.

“I take what nature creates and make it do new things that we want.”

But then I found myself with a degree in mechanical and aerospace engineering, and that was at the beginning of a realization that people needed to learn how to live sustainably. The United States was experiencing major disruptions in the oil supply in the 1970s, and many engineers were coming to the recognition that we would have to invent new ways of generating energy, as well as live less wastefully. President Carter set a national goal of reaching 20 percent renewable energy by the year 2000. I wanted to be part of that. I took a job at the Solar Energy Research Institute, but that only lasted a year owing to a change in administrations and, with that, a change in government focus. After President Reagan was elected, I moved farther west to attend graduate school at UC Berkeley, in California.

This was the beginning of the DNA revolution, when the world was waking up to another important realization: that we could manipulate the code of life. I became a biochemist — actually a biochemical engineer. But I had never studied chemistry and I didn’t know anything about biology. So, I threw myself into these new fields as a graduate student.

And then you earned a faculty position at Caltech. At the time, it was unusual for a young woman to be in this field. How did your colleagues react?

In my faculty position at Caltech, I was rare, but not the only woman. There were other female professors in chemistry and in biology. But I was only the ninth ever to be hired. I was young (30 years old), but I had a tenure-track position as an assistant professor and the first woman in chemical engineering. It was a bit of a battle to stay at Caltech, but I had enough supporters to win that battle — and the rest is history.

Apparently you once said you wanted to do your experiments “cheap and fast.” What did you mean?

Frustratingly, my first experiments didn’t work. I tried it the “gentlemanly” way, attempting to reason which changes would be beneficial. My colleagues were trying to understand how biology works by taking the science apart; they weren’t making anything better. Getting a little desperate, because I was going nowhere fast, I decided to let the system tell me what was important. I did this by making mutations at random and searching through them very quickly.

I wanted to be an engineer of the biological world, to reconfigure the molecules of life to serve human purposes. I wanted to build new proteins —those big, complicated biological molecules that catalyze the reactions of life. Some of my biochemistry colleagues didn’t like the way I approached the problem, though. Biochemists were taking a “design first” point of view — but no one knew how to design. I argued, instead, from the engineer’s point of view. That is, that how you do something doesn’t matter as much as whether you can do it. And whether you can do it quickly so as to be useful. So, that means you do it quick and dirty. Later on, you can figure out how you did it.

At that time, did you work day and night?

I worked hard then. But in 1990, after four years at Caltech, I had my first son. Anyone who’s had a baby realizes that you cannot have a baby and work twenty hours a day. I had to be more efficient with my time, and I had to give more power to my research group — the students who had signed up to work with me — so that I could go home to my husband and my baby, and then be back in the lab in the morning. I found staying at home was harder than going to work! I was always back in the office with a baby in my arms within a week or two of each one’s arrival.

In the 1980s, there was a change in attitude about women in science having children. With more women competing for key scientific and other careers, there weren’t as many traditional marriages. And without a wife at home to take care of the kids, the men struggled, too. But there also were more childcare options available.

We have to welcome women into the sciences and engineering, and if you’re going to welcome women, you’re going to welcome mothers. You’re going to welcome young fathers, too. I think that attitude has been hugely beneficial to women — and to men, because raising a family is more of a partnership than perhaps it was in the past.

You’ve won many awards. You won the National Medal of Technology, for example. You were the first woman to receive the Millennium Prize for Technology. And in 2018, you were awarded the Nobel Prize. How has this acclaim affected your life?

The last nine years have been a whirlwind, but for me that time is not marked by the prizes. It’s marked by the science we have done and the things that have happened in my personal life. I am still the same person, and I do the same things as I did before those awards. I work here at Caltech, I teach classes, and I run a research group, just as I did before. Perhaps I travel a bit more, but that is because my sons are grown up now.

You got the Nobel Prize for your work on “directed evolution.” Can you explain what that is?

It’s like breeding, but at the molecular level. A farmer can breed a better apple variety, a dog breeder can breed a new dog variety. In my research, we created new biological molecules by breeding the DNA in a test tube. Directed evolution uses the tools of molecular biology to create better biological molecules, like enzymes.

“Everybody says, ‘Oh, my technology is useful.’ But if nobody uses it, it’s not useful.”

In the past, if you wanted to breed a better racehorse, you had to be really good in choosing the two horses to breed, and then you hoped there would be a winner among the progeny. But today, if I want to breed at the molecular level, I can have three parents. I can mix DNA from 33 parents. I can mix species. I can make random mutations and control the level of those mutations. I have control over the underlying evolutionary processes — that’s an ability no one had before these technologies became available. The questions then became: How do you do it and get something that’s better than what you started with? And how do you do it on a timescale that matters?

I suppose I received the Nobel Prize for figuring out how to do it. We’ve made lots of enzymes that are used in industry, and students from my group have started companies that work on sustainable chemistry, such as making jet fuel from renewable resources. Some make nontoxic modes of agricultural pest control, and others make useful chemicals without generating much waste.

The rest of the world has adopted these methods to make pharmaceuticals in a clean way, to take stains off clothes in better laundry detergents, to reduce the energy requirement for making textiles, and to do a better job with clinical diagnostics. Directed evolution makes better enzymes for those applications and many more, new uses.

Why did you also start your own business?

Everybody says, “Oh, my technology is useful.” But if nobody uses it, it’s not useful. So, how do you get people to use your inventions? One way is to get them into people’s hands. And if no existing company wants to do that, you can start a new company and provide that technology.

My first big-time foray into business was my work with a friend of mine, Pim Stemmer, who started the company Maxygen as a way to do directed evolution. I was on the initial science advisory board, where I learned from people who knew how to start a company. And now I start companies. We began our first one in 2005 — that was 14 years ago — and have done a few more since then.

You must be very well organized?

I am hyper-organized. I’m usually up at five or six in the morning. I work at home in the mornings, and I try to get a lot of things done. There are a lot of telephone calls, editing of papers, and writing letters, and then I come into Caltech and spend the afternoon talking to students, having research group meetings, meeting visitors, teaching class. Then I go home, have dinner with my family if someone is home, and relax for a little bit, listen to books on tape, take a walk, do yoga. And then I go to bed. I don’t work at night. Maybe I did for the first year or two, before I had children. But once I had children, starting in 1990, I rarely worked at night.

In your private life, you went through some tragic times. Do you want to elaborate?

Well, we divorced five years after getting married. The marriage didn’t last because he had to move to Switzerland and I didn’t want to go to Switzerland. It was a difficult time because I had a small child. I met a wonderful man soon after, however, and had two more sons. That was lovely for as long as it lasted. He died in 2010.

Your second husband committed suicide. That must have been very hard.

Yes, it was. He suffered very badly from depression. It’s something I don’t understand. I think the last time I was deeply depressed was when I was 12. I now realize that I have control over my own self, and that’s the only thing I have control over. We had split up two years before he committed suicide, and he left me with three little boys to raise on my own.

But then tragedy struck again — your son died in an accident.

Yes. That broke my heart. And I miss him every day. He was very loving and outgoing, and a wonderful, talented person. He was 20 years old.

Have you had bright moments to compensate?

I had three of my four brothers, their wives, my two sons, and my son James’s wife, Alanna, all together at the Nobel Prize ceremony. Actually, we were together almost a whole week in Stockholm. Former students came, and friends and colleagues as well. I could see the pride and happiness in their faces. I was as happy as I’ve been in a long time.

You were once described as pushy, aggressive, all those things men normally don’t have to be.

I was pushy and aggressive, but I had to be. One time the president of Caltech asked me, “Why are you so arrogant?” I said, “Oh, my goodness, Mr. President. If I weren’t, I wouldn’t survive.” It was a survival skill back then; I believed in what I was doing, even when others did not, and I would not let them push me around. That attitude served me well at that point in my life, but now it doesn’t have to. That is, I don’t have to defend myself anymore. I try to smooth the rough edges. Of course, I had to be stubborn then; otherwise, I’d have to give up. And I’m also a somewhat impatient person, but I’ve been working on that, too.

The tough edges are made up of resilience. I don’t feel sorry for myself — that’s useless. So, when I got cancer, or when my son died, I could’ve said, “Boo hoo, poor me.” But instead, I said, “Okay, boo hoo, poor me, but let’s move forward.”

“When I got cancer, or when my son died, I could’ve said, ‘Boo hoo, poor me.’ But instead, I said, ‘Okay, boo hoo, poor me, but let’s move forward.'”

I like life. I like my family. I like my students. I like my work. I think it’s important to focus not so much on the bad things but, rather, on the good things, of which I have many. No one is guaranteed an easy time in life. When you live to be a certain age, you’ve been through it all. You’ve lost loved ones. You’ve lost things that matter a lot to you. Do you give up? No. If you’ve got children watching, if you’ve got students watching, how can you give up?

Some women have had to deal with sexual harassment. How did you deal with it?

There were certainly unwanted advances, but I always felt in control. If I didn’t like what some older professor was saying to me, I’d tell him to go jump in the lake. And then, of course, I also had more favorable attention as a woman. Because there were so few women in science, that could be a benefit. So, I just turned it on its head and said, “I will use this to my advantage rather than let it be a negative.” For example, when I had to speak to an audience that had never seen a woman engineering professor before, they were automatically wondering, “What’s she doing here?” So, yes, I had to do it better. I had to perform to a higher standard than men. And I made sure that when I opened my mouth, the men would listen to me — and keep listening beyond the initial curiosity.

If young people — especially women — are considering studying science, what do you tell them?

To do whatever they want to do. I tell them that I find science a great career. It’s flexible, especially academic research, which is great if you want to have children. In fact, that flexibility is something I value very much, but not everybody is cut out for academic science. For example, being an academic can be stressful. Not everyone wants to be responsible for running a group, coming up with ideas, and obtaining the funding.

Everyone’s different — that’s also what I emphasize. If you follow the same path as the others, don’t forget your own path as well. That lack of diversity stymies innovation. Evolution teaches us that unless we have diversity, we go extinct. And the way to be innovative or the way to find what you love to do is to try different things. Trying different things served me very well.

What is your message to the world?

Take care of the people around you; it will bring you strength and happiness that will then propel you to do creative things. And stay curious.

I’ve seen many people come and go, and what I would like to remain of me is to be in the good memories of the people who are still here. I’d like to be remembered the way I remember my grandmother. And I’d like to be remembered the way I remember my son. Leaving some positive influence on others that makes people happier.

What have you learned from nature?

That biology can do anything. That nature is the best chemist on the planet (and probably the rest of the universe). Not only did she invent all these wonderful life forms and the chemistry that makes them, but she also invented the design process of evolution. And this is the magic trick that gives nature its huge advantage. Now I have it, too.

I’m not a creator; I’m an evolver. I’m a breeder. Nature creates. I take what nature creates and make it do new things that we want.

Herlinde Koelbl is a German photographic artist, author, and documentary filmmaker. She has published more than a dozen photography books and has received numerous awards for her work, including the Dr. Erich Salomon Prize in 2001. You can learn more about her at www.herlindekoelbl.com. This interview is excerpted from her book “Fascination of Science.”