In Conversation With George Shultz, Legendary Statesman and Economist

What is it like to sit in the Oval Office and discuss policy with the president? To know that the decisions made will affect hundreds of millions of people? To know that the wrong advice could be calamitous? For his book “When the President Calls: Conversations with Economic Policymakers,” Simon Bowmaker, a professor of economics at the Stern School of Business, spoke with 35 economic policymakers who served presidents from Nixon to Trump, asking them to shed light on their career paths and experiences.

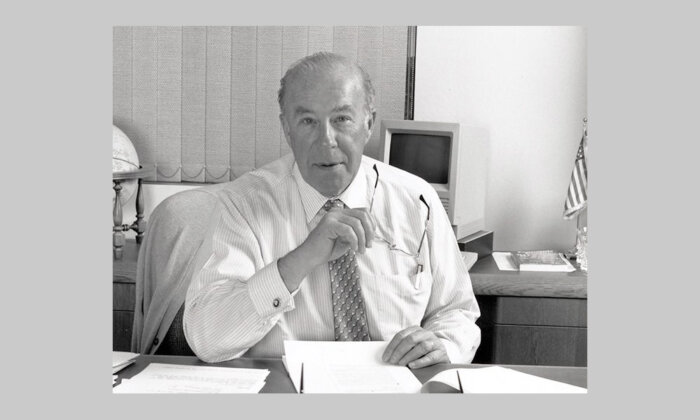

Among those interviewees was George Shultz, a legendary figure in American politics best known for helping to forge a new era in American-Soviet relations and bring a peaceful end to the Cold War. Shultz, a veteran statesman who held four U.S. Cabinet positions and served under three presidents, died on Saturday at 100 years old. The following interview, excerpted from Bowmaker’s book, finds Shultz reflecting on his time in public service and what economic policy looks like in action. It took place in Shultz’s office at the Hoover Institution in Stanford, California, on July 19, 2012.

Background Information

Simon Bowmaker: Why did you become an economist?

George Shultz: I grew up in the 1930s, when the country was in a deep depression. Economics was the subject on everybody’s minds, including mine. When I went to Princeton as an undergraduate, I took some courses in economics and became even more interested. That’s how I got started.

Entering the Policy World

Bowmaker: What does an economist bring to the policy world that others do not?

Shultz: An economist brings a disciplined way of thinking about problems that has been worked out over the years. It helps us understand what kind of data to produce, how it should be organized and then used to guide us to the best policy.

It is also true that economics is a strategic science because it makes us think ahead, take into account indirect consequences, and consider variables that might not be of direct interest.

Furthermore, an economist knows that policies that are enacted today do not have immediate effects: they operate with a lag, which causes a problem in a political context because a politician wants instant results. The economist’s lag is a politician’s nightmare.

Bowmaker: Your first policy position was senior staff economist at the president’s Council of Economic Advisers during the Eisenhower administration. Did you view yourself as having strong policy positions or simply as a hired professional serving CEA Chairman Arthur Burns and, indirectly, the president?

“The economist’s lag is a politician’s nightmare.”

Shultz: I had policy views and I already had a track record of publication in labor economics, which is why I was asked to join the CEA. My predecessor had been another labor economist, Al Rees from the University of Chicago, who I knew very well.

I found it a very exciting year, and I hope that I made a contribution. I certainly benefited so much from the experience. I learned a lot about policy, a little about Washington, and a great deal about federal statistics because Arthur Burns was from the National Bureau of Economic Research [NBER]. He was very interested in those statistics, and I was involved in various committees that tried to improve the time-series data, so that was valuable work.

Bowmaker: How would you describe Arthur Burns’s approach to his role as CEA chairman?

Shultz: An early chairman of the CEA was a lawyer named Leon Keyserling, who regarded the council as a place for advocacies of the administration’s policies, which led to Congress becoming very disillusioned. But when President Eisenhower was elected, he persuaded Arthur Burns to be chairman of the CEA, and Arthur rebuilt the professional stature of the council. He would not give interviews, make public speeches — and when he testified before the Congress, he would not tell them anything about his views on the economy. His view was that he was not the economic adviser to the American people or to the Congress; he was the president’s economic adviser. I would argue that the CEA has drifted somewhat since then, and its members appear to be public figures, but I think that the residue is still fundamentally a very professional organization.

Bowmaker: You returned to academia after leaving the CEA, and in 1962 you were appointed dean of the Graduate School of Business at the University of Chicago. Did this experience prove useful for your high-level government positions that would follow later in your career?

“You have to get used to the art of management through persuasion.”

Shultz: Being a dean helps you as a Cabinet member because that role has a great deal of responsibility but practically no authority. You can’t order the faculty to do something, you can’t order the students to learn, and you can’t order the alumni to give money. And so I always felt that I had an advantage over my colleagues who had worked in business or in positions where they told people what they had to do. As a Cabinet officer in Washington, you have responsibility, but the White House is your boss, and you can’t spend a dime that the Congress doesn’t appropriate. You have to get used to the art of management through persuasion.

As Secretary of Labor

Bowmaker: You were appointed secretary of labor in 1969. How did that position arise?

Shultz: I was out here at the Center for Advanced Study when my year was interrupted by my becoming secretary of labor. I was chairing a task force for candidate Nixon in labor relations. One of the things that he did, which I thought was very intelligent, was to appoint a task force in a variety of these subjects with the understanding that if he was elected, the ideas that were developed during the campaign would be fleshed out in more detail.

Bowmaker: How did your background as a labor economist have an influence on the type of secretary that you wanted to be?

Shultz: I was a labor economist who had written about issues such as emergency disputes, but I had branched out into the real world by becoming involved in mediation and arbitration work, and I also had very vivid experiences in the arena of discrimination on the job. So I definitely brought views to the role of secretary of labor.

Bowmaker: Did you make it clear to President Nixon your intended approach to the role?

Shultz: It was an interesting experience being appointed to the position of secretary of labor. Nixon decided to announce his Cabinet all at once, not one at a time. He told me not to say anything about the appointment until there was an official announcement. I informed him on the telephone that I would like to have a personal meeting with him about the position. He replied, “Well, I’ll be in Los Angeles next Monday. Come and meet me at around 10:00 in the morning.” I spent the weekend saying to myself, “What kind of secretary am I going to be? I have views about A, B, C, D, and E subjects.” When I met him, I said, “I have accepted the job, but I want you to be clear about what you’re getting because these are my views, and I’m probably not going to change. If they’re not satisfactory, it’s best that you announce somebody else for the role.” I’m glad I did that because I went through several controversial areas that ended up emerging during my time as secretary of labor, and I was able to do things with Nixon’s support that were based in the wake of our conversation.

Bowmaker: Two of those controversial areas included the Longshoremen’s Union dispute and the ending of the dual school system in the South. Can you tell us about your work in those areas?

Shultz: Yes, I had to handle the Longshoremen’s Union dispute that Lyndon Johnson and the Supreme Court had declared to be a national emergency. I thought it wouldn’t be one. I had said to President Nixon in our earlier conversation, “Mr. President, your predecessor and the Supreme Court were both wrong. This dispute will not cause a national emergency, and once people get it into their heads that they’re not coming to the White House, I can mediate this dispute and get it settled.” And so we then sent a big message to collective bargaining that “you’re not going to get bailed out by the White House. You’ve got to work your problems out for yourself.” That succeeded.

The president also decided to end the dual school system in the South, and I was his point man in managing the process. All these years after the Brown decision, schools were still racially segregated in seven southern states. And so we developed a strategy in which we identified people of significance in those states (equal numbers of blacks and whites) and invited them to the Roosevelt Room at the White House to open up the discussion. It was not easy but it worked, and I saw the president do an admirable job up there against a great deal of political advice. That’s an example of one of the many terrific things that Nixon accomplished. Unfortunately, Watergate is so dominant in connection with his name that people tend to forget them.

As Director of the OMB

Bowmaker: In 1970, you were appointed director of the newly created OMB. Were you attracted to this role?

Shultz: Yes. There isn’t another position in which you get to understand how the federal government works. The budget tells you what the president’s priorities are, and of course as an economist it is a big deal to have the opportunity to oversee the expenditure side of fiscal policy.

Bowmaker: What changes did you make at the OMB, which replaced the Bureau of the Budget?

Shultz: We had to develop the M in OMB. One of the things we learned fairly quickly was that the only way to have any managerial impact was through the OMB’s budget officers, who had a lot of clout.

Bowmaker: At your first meeting about the job, President Nixon told you that it was his budget, not yours. Your predecessor, Robert Mayo, apparently thought that it was his own budget. Without this conversation in the Oval Office, would you have approached the role differently or not?

Shultz: No, there wouldn’t have been any question in my mind that it was the president’s budget I was working on, although Nixon didn’t like the budget process and tended to be more interested in foreign affairs and so on.

But he also did something interesting in that first meeting. He said, “I’m preparing a new suite in the West Wing. Hold your meetings there. That will give people the geographical notion of where the authority is, and if the meeting is bigger than your office can accommodate, use the Roosevelt Room. But make sure people come to the White House so they know it’s my budget.” By the way, people kill to get suites in the West Wing. I had two offices and a big reception room.

When I became secretary of the treasury a couple of years later, he told me, “Keep your office and be assistant to the president for economic policy, which means you are responsible for pulling people together who are interested in economic policy. And when you are having your Treasury meetings, have them in the Treasury Room, but when they are intergovernmental meetings, have them in the White House.” That worked very well. I wound up having an office in the West Wing for four years, and because of that I got an idea of how the presidency works as well.

As Secretary of the Treasury

Bowmaker: How would you describe the economic environment that you inherited when you were appointed secretary of the treasury in 1972?

Shultz: When I arrived at the Treasury, the exchange rate system was in turmoil after the collapse of Bretton Woods, but I found that there was no alternative plan in place. So I spent the summer with colleagues, such as Paul Volcker, developing one, which was then announced with the president’s approval. Although the plan was not adopted as such, you could almost hear the world heave a sigh of relief that the US was in the game with a plan and a proposal.

The second issue was wage and price controls. I had opposed this policy before I became treasury secretary, so I started the process of dismantling them. We were making headway when the president decided to reimpose them. I said to him, “Get yourself a new treasury secretary. I’ll stay until you find one, but I’m out of here.”

Bowmaker: Why were you so opposed to wage and price controls?

Shultz: When I was director of the OMB, I had given a speech entitled “Steady as You Go.” I argued that we have the budget under control, we have a good monetary policy with a lag, inflation will come down, steady as you go. But wage and price controls were imposed, which was a huge intervention in the economy, and so the political process had overwhelmed what I regarded as pretty good advice. The 1970s were a bad decade in economics in this country.

“Some decisions you win, and some you lose — but as long as you feel that in a broad sense the administration is doing something compatible with your views, that’s OK.”

Bowmaker: Do you think economists in government fear having to support political decisions that they do not think are economically justified?

Shultz: Some decisions you win, and some you lose — but as long as you feel that in a broad sense the administration is doing something compatible with your views, that’s OK. But economists have to stick to economics and not try to be amateur politicians. They are no good at that. They are better off just saying, “Here are the economic implications,” and trying to argue for the right policy on that basis. You can make things more palatable in the way that you phrase things, but stay out of the politics.

As Chairman of President Reagan’s Economic Policy Advisory Board

Bowmaker: After almost 10 years working in the private sector, you returned to government in 1981 as chairman of President Reagan’s Economic Policy Advisory Board. How did that position arise?

Shultz: I had gotten to know Ronald Reagan when I came back from the Treasury. He invited me up to Sacramento for what turned out to be a very long lunch. Reagan grilled me about how the federal government worked, particularly the budget, and then we had a dinner party at my house, where Milton Friedman, Bill Simon, Alan Greenspan, Marty Anderson, and Michael Boskin were present. He argued with all of us and more than held his own when we put him on the spot. I could see how well-grounded he was and how he thought through issues. I was very impressed.

Then he invited me to put together and chair an economic advisory committee during his campaign, which I did, and we produced a report for him, a very big part of which was published in the Wall Street Journal. It was very good.

As you said, for the first year and a half of his administration, I then chaired his Economic Policy Advisory Board. It was more or less the same group as the committee, and he paid attention to us because we were his pals from the campaign. We thought the way he did, and in office when there were pressures to compromise, we would come in and say, “No. Stick to your guns.” He appreciated that, although his staff didn’t.

Bowmaker: You just mentioned that you could see how Ronald Reagan thought through issues. Could you elaborate?

“[Reagan] knowingly took a short-term hit to achieve a long-term objective. I thought in some ways that was his finest hour in terms of the economy.”

Shultz: Ronald Reagan was not somebody to put his finger in the air to find out which way the wind was blowing. He would dig down and say, “What makes most sense?” And then he would stick with it even if it might be unpopular. He always thought that if it’s good for the country, then he could persuade people that it’s good for them. An outstanding example was when he took office. At the time, inflation was very high, and in our written recommendation we had said that you couldn’t have a decent economy as a result, and that the way to get rid of it was to have a disciplined money supply, which Fed[eral Reserve] Chairman Paul Volcker was in the process of producing. Reagan’s political advisers said to him, “Mr. President, there’s going to be a recession, and you’re going to lose seats in the midterm election.” He replied, “Somebody has to do something about inflation.” In doing so, he pretty much held a political umbrella over Volcker so that we could do what needed to be done; he knowingly took a short-term hit to achieve a long-term objective. I thought in some ways that was his finest hour in terms of the economy.

As Secretary of State

Bowmaker: Was there anything that you learned in your business career that helped prepare you for your next role as secretary of state?

Shultz: I was in the construction industry, which had a big international component to it. We would go to different countries around the world, hire people, pay them, and occasionally fire them. That allows you to learn so much about how a particular country works, a place that you wouldn’t otherwise have had a clue about when you are meeting with government ministers. In that respect, my business background was a very educational experience for me.

Bowmaker: In your Richard T. Ely Lecture in 1995 [“Economics in Action: Ideas, Institutions, Policies”], you said that “I have increasingly realized that my training in economics has had a major influence on the way I think about public policy tasks, even when they have no particular relationship to economics.” Can you give some examples of when this was relevant in your role as secretary of state?

Shultz: As I said earlier, economics is a strategy science, which tells you that all kinds of problems are going to come up. When I was secretary of state, I had to deal with Americans being taken hostage. The basic strategy, which is almost impossible to follow, is that you lower the value of the hostages and raise the costs of taking them. That’s straight out of an economics textbook. If you pay for hostages, you are simply encouraging people to take more of them, and that is bad from a strategic point of view.

“If you pay for hostages, you are simply encouraging people to take more of them, and that is bad from a strategic point of view.”

I remember when a writer for the Wall Street Journal, Gerry Seib, was taken hostage in Iran. The newspaper had been whooping and hollering in their editorials, and they came to see me to ask what we were going to do about it. I said, “I’ll tell you, but you won’t like it.” They replied, “What’s that?” I said, “The game here is to minimize the gains they get from what they’re doing and maximize the cost. And so the bigger the hullabaloo you make, the bigger the prize for them. You’ve made your point, so why don’t you just shut up? We can work it through the Swiss to their embassy in Tehran or their intersection. We’re trying to get the message across to the Iranians that this is going to be very costly for them. If you can keep the benefits that they see down, we have a chance of getting somewhere.” They agreed, and after about two or three weeks, we got Gerry Seib out. That was an interesting lesson.

General Thoughts on Economic Policymaking

Bowmaker: Can you give some examples of fallacies, misconceptions, or misinterpretations that affect policy debate in this country?

Shultz: Understanding the effects of taxes is probably the biggest one. Some people think that higher taxes lead to a less vigorous economy, while others believe that you can put a tax on something and it doesn’t matter. I remember when they taxed yachts here in California. Somehow, the politicians didn’t realize that yachts can move. What a revelation! And so all the yachts went up to Oregon. And the same thing happened with private planes. We collect nothing in revenues because people react to the imposition of the tax. I don’t know why it is so hard for politicians to understand that. Or maybe they don’t care and instead just pat themselves on their backs and say, “Look what I did — I went after those guys with yachts and private planes.”

Bowmaker: Which aspects of the institutional framework for making economic policy in this country work well, and which need to be reformed?

Shultz: I don’t think there is an institutional answer to the problems that we have. I do think we would be well off if we had a basic revision of the GDP [gross domestic product] figures. The categories used to describe the economy were created by some brilliant people at the NBER back in the 20s and 30s, but the economy today bears practically no resemblance to the economy then. When something new is invented, like a cell phone, where are we supposed to put it? When we can’t think of a place, we call it a service, which means that today we call ourselves a big service economy. But when your description isn’t accurate, you’re also not getting the dynamics right. And so I’ve been recommending to the NBER that we have to start with a clean sheet of paper, redescribe the economy, trace that through, and see whether that changes the way it looks.

Personal Reflections

Bowmaker: What value has your public service had to you, and which aspects of public service do you miss most?

Shultz: I always considered it a great privilege to have had the opportunity to serve my country. When I was secretary of labor, director of the OMB, and treasury secretary, there were things that needed to be done, and it was very rewarding to be part of them. And when I was secretary of state, the tectonic plates of the world changed, and I certainly learned a great deal during those interesting and important times.

I miss working with the president, of course, but also all the wonderful career civil servants. I was told, for example, that a Republican couldn’t do anything in the Labor Department because it was a wholly owned subsidiary of the labor movement. But I found that if you give them professional leadership, they’ll work their hearts out for you. And it was the same at the OMB, the Treasury, and the State Department. The people there were extraordinarily talented.

Bowmaker: How did your personality affect your style and approach as a policymaker?

Shultz: I had my way of doing things, and it seemed to work pretty well. You need to have a strategy and let people know what it is, and have a structure that emphasizes the importance of what I would call line organization. Too many people hire bright young staff and then try to run things through them. I think that’s a bad mistake, and something that the White House is doing more and more. There needs to be a line organization that you can build up and make stronger, which allows you to work effectively. Then, of course, there is the importance of leadership, integrity, and accountability. I’m not trying to be a martinet, but in every job, if you don’t do it properly, there have to be consequences.

Bowmaker: As a policymaker, which decisions or outcomes were most gratifying?

Shultz: When I was secretary of state and people asked me about my foreign policy, I would say, “I don’t have one. President Reagan has one. My job is to help him formulate it and carry it out. But it’s not my policy; it’s his policy.” I had two private meetings with the president every week in which we talked by ourselves. But I didn’t use those meetings to reach decisions. Instead, I used them to share reflections on issues that were coming at us.

Bowmaker: On the other hand, there must be some things, in hindsight, that you’d like the opportunity to do differently. What are they?

Shultz: The worst day of the Reagan administration was when the Marine barracks were blown up in Beirut and 241 servicemen were killed. You look back and think about how that might have been avoided.

Simon W. Bowmaker is Clinical Professor of Economics at the Stern School of Business, New York University, and Visiting Senior Fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science.