When Kids Ran the World: A Forgotten History of the Junior Republic Movement

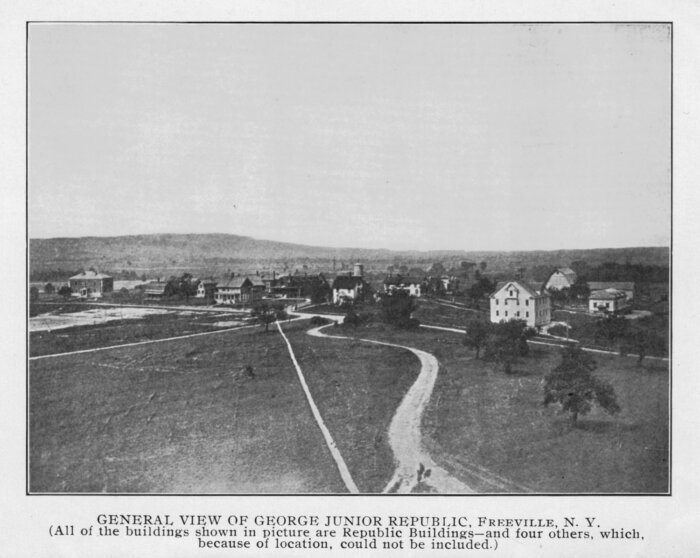

Travelers should be sure to visit the curious community in Freeville, New York, where boys and girls were in charge, wrote Baedeker’s turn-of-the-20th-century guide to the United States. This “miniature republic modelled on the government of the United States” was well worth a detour to observe the “legislature, court-house, jail, school, church and public library” staffed by citizens aged 14 to 21, most of them immigrants or impoverished youth.

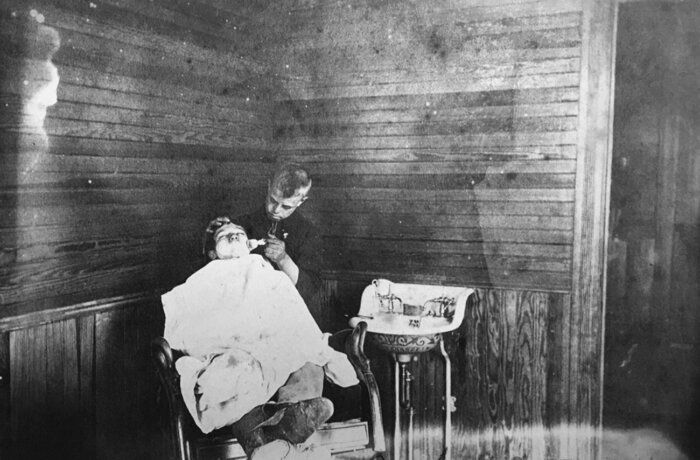

Of course, these young Americans were not actual members of the civil service, but their adultlike activities were exceedingly realistic nonetheless. They “elect their rulers, make and enforce laws, and carry on business just as adults do in the greater world,” author James Muirhead marveled.

The brainchild of philanthropist William R. George, the George Junior Republic (est. 1895) was hardly alone. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a motley crew of reformers helped scores of American youth to construct thousands of cities, states, and nations around the country “on a similar plan” as later editions of Baedeker’s explained. In these child societies, boys and girls of all races and ethnicities and from across the economic spectrum were the officials and citizens. They made laws, sat for civil service exams, and paid taxes. They constructed buildings and swimming pools, ran hotels and restaurants, and printed newspapers and currency. They opened juvenile libraries and museums, tended vegetable gardens and zoos, organized cooperative stores and charities, staffed banks and post offices, performed in theaters and on radio broadcasts, and administered hospitals and schools of law.

During an era of vigorous campaigns against young people’s presence in the nation’s labor force and on its streets, junior republics supplied opportunities for youth to play adultlike roles in age-restricted worlds. Some, like George’s later “junior municipalities,” expanded their activities beyond campuses and clubhouses into the surrounding communities, incorporating public spaces into these civic dramatizations.

News media and travel guides reported regularly on elections and publicized the latest accomplishments of the inhabitants, some as young as five.

Each of these environments was a “village like any other” as George frequently observed of Freeville. He insisted that the junior republic’s simultaneous resemblance to and separation from the “big republic” — in his words, “no one can tell where the big Republic leaves off and the Junior Republic begins” — enabled young people to learn valuable life skills and called for building still more such similar juvenile societies across the nation.

News media and travel guides shared his enthusiasm and his interpretive framework. They reported regularly on elections and publicized the latest accomplishments of the inhabitants, some as young as five, whose daily lives were “passed in experiences and obligations of mature citizens,” while reassuring visitors and readers that the adultlike experiences that improved kids’ character “without taking away their independence” were merely “miniature” and “model” versions of their elders’ activities: work-like educational and recreational experiences rather than work itself. Later, they reported stories of lives transformed upon graduation into adult society, thanks to the training these youth-only settings supplied, particularly for immigrant, working class, and minority youth.

From Chicago judge Sidney Marovitz (Boys Brotherhood Republic) to Milwaukee mayor Carl Zeidler (Newsboy Republic), from U.S. surgeon general Julius Richmond (Allendale) to University of Michigan labor economist William Haber (Newsboy Republic), from Philadelphia superintendent of schools Constance Clayton (Youth City) to Motown songwriter Alfred Cleveland (Hill City), from Pulitzer Prize-winning journalists William Dapping (George Junior Republic) and Theodore White (George Junior Republic) to actors Steve McQueen (California Boys Republic) and Jerry Stiller (Boys Brotherhood Republic), distinguished and lesser-known alumni credited their republic experiences with offering them practice in the personal and professional skills critical to their successes in later life.

The massive movement that mobilized about these curious communities drew in psychologists and educators, ministers and police, juvenile judges and businesspeople, playground advocates and the American Legion, efficiency experts and good government activists, the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs, and the National Youth Administration. International curiosity brought numerous visitors to the republics and even inspired adaptations abroad.

Impressive for the scope of support it generated, the junior republic movement was on the leading edge of an even broader trend. In an era when public opinion increasingly favored segregating young people from the world of adults, the Freeville republic and its many descendants allowed young people to simultaneously inhabit both a rural village and a miniature United States, to simultaneously be kids from the tenements of New York City on summer vacation and U.S. senators debating matters of national importance — in short, to live what American Institute of Child Life director William Forbush called a “double life.”

Similar opportunities lay at the center of the era’s broader efforts to fashion a new identity for the nation’s youth. Educators and youth workers like Forbush soon discovered that as young people playing adult roles seemed to enjoy adjusting themselves to the era’s new social expectations, these virtual adults were also helping to build and operate the institutions that sheltered them as they learned and played.

In schools and settlements, YMCAs and boys and girls clubs, churches and summer camps, orphanages and reformatories, the many institutions devoted to serving young people embraced the component activities of these child societies. Vocational education and home economics enabled kids to construct their housing and prepare their meals. Youth congresses and junior sanitation squads helped them to maintain order in their institutions and neighborhoods. Public officials, admiring children’s professionalism as police, judges, and sanitation workers inside child-only societies, followed with junior police squads, junior juvenile courts, and junior health inspectors — making city streets the settings for role-playing games in which kids arrested peers, adjudicated delinquency cases, and kept their communities clean.

The result was that the dual experience of protected childhood and of virtual adulthood that characterized participants’ lives inside junior republics became a defining feature of modern youth. In an era when educators, youth workers, and public officials aimed to remove children from the labor force and public life, these educational and recreational programs provided a middle ground for young people to role-play adult jobs inside child-only settings to prepare for their future lives. Public emphasis on these activities’ developmental productivity for youth did not negate their economic productivity, however — suggesting that the individuals and institutions tasked with child protection redescribed child labor as much as they reduced it — and that kids played important roles constructing youth-serving institutions and the modern state.

The Freeville republic was not merely a microcosm of adult society but a microcosm of the American youth experience itself.

Over time the junior republic movement and broader applications of role playing in youth programming continued to evolve. During World War I, young people in republics and related programs directed attention to the war effort, manufacturing military goods, gathering scrap metals, canning vegetables, hawking war bonds, and distributing government information.

In the postwar period, along with the rise of mass automobility, schools and police departments deployed children for traffic management. From the 1930s, children’s exposure to newspaper publishing, radio broadcasting, and filmmaking at schools and youth-serving institutions provided public relations for these institutions to peers and the wider community. Across these activities the belief endured that educational and recreational variations on adult occupations and the environments associated with childhood stood outside the market, opportunities for child protection rather than expansions of the child labor pool.

The lack of a sustained and unified national junior republic movement — William R. George’s ultimate ambition — marked not George’s failure but rather the popularity and broad diffusion of his republic’s core principles. The Freeville republic indeed became a village like any other well beyond George’s original intent, not merely a microcosm of adult society but a microcosm of the American youth experience itself.

Cataloging the diverse roles that young people performed on a massive scale — for example, as truant officers, health inspectors, and traffic police — identifies their previously hidden contributions to American political development as they learned and played. With the normalization of the sheltered childhood, the importance of role-playing adulthood receded, but its deep influences on American cultural and economic history remain.

Jennifer S. Light is Director of the Program in Science, Technology, and Society at MIT, where she is Bern Dibner Professor of the History of Science, and Technology and Professor of Urban Studies and Planning. She is the author of “States of Childhood,” from which this article is adapted.