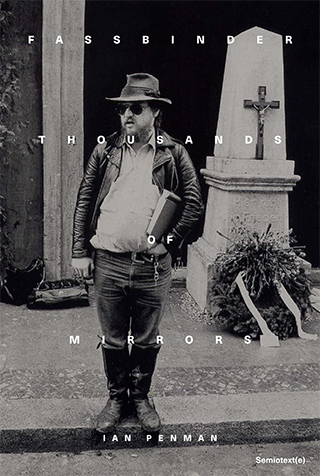

Fassbinder Himself (An Essay in Fragments)

Melodrama, biography, cold war thriller, drug memoir, essay in fragments, and mystery, “Thousands of Mirrors,” from which the following text is excerpted, is cult critic Ian Penman’s long-awaited first full-length book: a kaleidoscopic study of Rainer Werner Fassbinder. Pounded out in a few months “in the spirit” of RWF, who would often get films made in a matter of weeks or months, “Thousands of Mirrors” presents the filmmaker as Penman’s equivalent of what Baudelaire was to Benjamin: an urban poet in the turbulent, seeds-sown, messy era just before everything changed. The result is a beautifully written and extraordinarily compelling work — a mosaic-like portrayal of Fassbinder and a story of creativity in all of its complexity.

17.

In one of the last months of his life, he is hugely impressed by something Jane Fonda says to him during a phone call.

In his foreword to the 1987 book “Love Is Colder Than Death,” producer Robert Katz relates an incident from Cannes 1982. Fassbinder was riding high, “Querelle” was about to be released, and he was already thinking about another project — “Rosa L,” a film about Rosa Luxemburg. He was even angling to get Jane Fonda to play the German socialist firebrand. At one point, Fassbinder took a call from Fonda.

“What’d she say, Rainer?” He looked very taken. “She said, ‘This is Jane Fonda herself.’” The next day, whoever got Rainer on the phone heard him answer, “This is Fassbinder himself.” In English.

18.

No, not merely my representatives or agents, all those I routinely use to screen calls, juggle requests and offers, get out of tiresome agreements I no longer wish to honor; not any of those who routinely speak in my name, but… I myself.

A seeming whim or gag: “Oh listen to me, big fat sweaty Rainer Werner playing the grand diva!”

But I notice that in so many of his interviews over the years there is a detail that is nothing like a joke. He talks over and over again about “self-identity,” how this was the very thing that nagged at and motivated and obsessed him, how it was in fact the one core thing, finding your true self and becoming identical with it.

19.

Wasn’t it precisely all his unceasing and unrelenting being himself that finally did for him? In other words, was Fassbinder himself really Fassbinder, himself, or was it just one more affectation or exaggeration or mask from a now overbearing, faster and larger-than-life, legend-in-the-making persona? Ronald Hayman concludes his 1984 book on Fassbinder with this cogent, pithy, indisputable verdict: “He needed the legend, and he sacrificed himself to it.”

20.

Against the backdrop of what was then still considered the necessary propriety of mainstream culture, Fassbinder did indeed look like a slob, a barbarian, a punk anarchist queer. In Germany he was a tabloid figure, a scarcely conceivable amalgam of Bertolt Brecht, Joe Orton, Daniel Cohn-Bendit, Sid Vicious, and Orson Welles. A monster of sexual indulgence and shock horror left-wing quotes and bad drug rumors, alongside the outrageous workload. They called this monster by his initials as if to temper his outsize reality with a little compression or economy: RWF. And this arms-length persona of the monster RWF became a convenient baffle against the noisy demands of fame. Did he in fact suicide himself, by trying to live up to an exaggerated version of himself at large in all the mirrors of the world?

21.

They didn’t like him because he was out, loud, outspoken, clever, willful, paradoxical, explosive. If he had just produced one careful, tasteful arthouse masterpiece every five years or so, no matter its subject matter or supposed politics (something like “Death in Venice” or “Teorema,” say) it would have been far more acceptable; but he went at it like a one-man revolution. If there is a thread that links the films (and the hurt, abused, doomed characters that people them: from Ali to Fox to Elvira to Veronika), it’s the feeling that there is something badly wrong with the state of post-war Germany. In its soil and its sky, its motives and its alibis, its over-reliance on logic and overarching greed and pervasive dissatisfaction. Like the characters in Walter Abish’s novel “How German Is It” (1980), people go about their aspirational lives while, under their feet, is a dark and unexcavated past. There may have been a post-war economic miracle but it was bought with the lives and souls of many unwitting victims. At the expense of a basic humanity: a dreaming, desiring, demanding humanity.

22.

Throughout the 1970s, he was written about (celebrated and criticized, both) in a way that others simply weren’t. Among European filmmakers Fassbinder was the most discussed, most controversial, most divisive. Subject of both the most biased and negative press, but also the most considered writing, in a way that simply didn’t apply at the time to contemporaries such as Wenders and Herzog. He was part of two or three parallel countercultures, and he was also part of the public discourse, positioned at the hot center of things. He had cultural impact, was talked about, argued over, could not be ignored.

23.

Four decades on the messiness remains; he hasn’t become a smoothed-out icon or convenient role model; something in him still resists such easy appropriation. Too untidy and paradoxical. Difficult to canonize, difficult to mourn. Difficult to assimilate. He is the opposite of those modernist figures who leave behind a tiny nest of fragments, like the remains of an afternoon picnic: the cult of the little and the lost, the sliver and the fragment. He is the opposite of all that. He is an entire town, region, conurbation, country; die Fassbundesrepublik.

24.

Is there coherence among the works? Can we arrange them into a unity? We can tot them up, certainly, but even then… there are films, TV one-offs, two TV series, plays, acting performances, writings, interviews. There is now a curatorial Fassbinder Foundation, but is there an easily summarizable Fassbinder ethos or aesthetic? An RWF brand? Or does he simply smear all such notions into a glorious, disheveled, contradictory mess? And is some aspect of this fundamental untidiness why he doesn’t seem to have had the thriving afterlife a lot of us expected? At various points in the last few years, scrolling through a social media timeline of sexual fluidity, tantrums, locked-in lives, queer pol, trans activism, cinematic nostalgia and seven types of ambiguous dysfunction… I often wondered: well now, how come Fassbinder isn’t hailed as king and absolute ruler of this wild and tattered kingdom?

25.

Always something monstrous about Fassbinder, even before he became the mythical beast RWF.

One of the reasons his reception is still unclear is that it is still (perhaps more than ever) a difficult thing to reconcile all his manifold contradictions — if reconciliation is truly what we want or consider appropriate in this case. There is no obvious takeaway moral. On one hand he might be viewed as someone at the tail end of modernism, with all its arrant sincerity, belief in revolution, big narratives, production values, masterpieces. On the other, he presents as jumpy and garish and nasty and grungy and punky and clubby and cokey and even something of a bully and a troll. Opulence. Bright colors. Queer characters. Sharp design. Anti “masterpiece” — just fan them out, all the divergent, devious, deviant, dangerous, doleful films, one after the other. Let history concern itself with reasoned evaluation.

26.

The unholy trinity: Fassbinder the artist, “Fassbinder himself,” and the mythic ogre RWF.

Ian Penman is a British writer, music journalist, and critic. He began his career at the NME in 1977, later contributing to various publications including The Face, Arena, Tatler, Uncut, Sight & Sound, The Wire, The Guardian, the London Review of Books, and City Journal. He is the author of “Vital Signs: Music, Movies, and Other Manias,” “It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track,” and “Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors,” from which this article is excerpted.