A Master Perfumer's Reflections on Patchouli and Vetiver

For perfume makers, each smell carries with it a multitude of associations and impressions that must be carefully analyzed and understood before the sum of all its parts emerges. All perfumers have their own idiosyncratic methods, drawn from their individual olfactory experiences, for classifying fragrances.

In his book “Atlas of Perfumed Botany,” virtuoso perfumer Jean-Claude Ellena leads readers on a poetic, geographic, and botanical journey of perfume discovery. Ellena offers a varied and fascinating cartography of fragrances, tracing historical connections and cultural exchanges. Full-page entries on plants ranging from bergamot to lavender are accompanied by detailed and vivid full-color botanical illustrations by Karin Doering-Froger. Two of those entries, on patchouli and vetiver, are excerpted below.

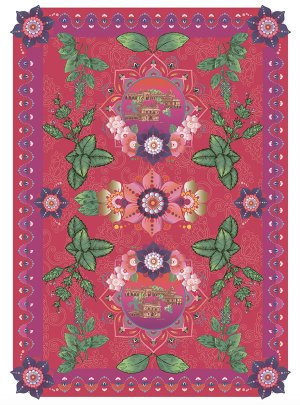

Patchouli

Pogostemon cablin

In 1968, I was 20 years old. Young people of both sexes perfumed themselves with essences of musk that did not really smell like musk (no one knew its actual odor), sandalwood, and patchouli. We rejected the bourgeois values of the world we had come from, and we challenged authority, conventional ways of life, religion, and consumer society. The musk and sandalwood had been manufactured chemically, but we thought we were buying something pure and natural. We went to bazaars and drugstores, not perfumeries. Only the patchouli was real, judging by the cost. Synthetic sandalwood and musk had been exported from France or the United States to India, only to wind up coming back to the West. The cheap, low-quality flasks in garish colors and imitation gold guaranteed the products’ authenticity in our eyes. It seemed to us that India, a land of great antiquity and home to diverse cultures, was where our dreams and utopian fantasies could all come true.

Patchouli was the fragrance of our generation. Smelling like the earth, undergrowth, youth, and freedom, it connected us to the imaginary world born of 19th-century Romanticism, when the word “patchouli” first appeared. In a commentary on Baudelaire, André Guyaux noted that the poet “didn’t need to go looking far for a little jar of heliotrope or tuberose, a bag of peau d’Espagne or a cashmere shawl redolent of patchouli cast on a sofa” to find himself spirited away. We, too, wanted an earthly paradise that wasn’t artificial. Perfumes that contained such elements in profusion were Patchouli (Réminiscence, 1970), Aromatics Elixir (Clinique, 1971), and Gentlemen (Givenchy, 1974). Fifty years have passed since then, and patchouli no longer has the same currency. Our sense of smell is different now, and our memory has other points of reference: wax, cigars, and pu-erh, the tea of emperors.

Patchouli was the fragrance of our generation. It smelled like the earth, undergrowth, youth, and freedom.

Perfumers first started using patchouli during the Second Empire; its dried leaves added value to shawls from Kashmir by imparting a pleasant scent and protecting them from mites during shipping. The aristocracy and haute bourgeoisie were so enchanted that an essential oil was soon being extracted. From when I was still an apprentice in the 1960s, I remember the giant bales, wrapped in jute. We would cut them open and scatter the contents on the ground to return the leaves to their natural state; then we loaded the leaves into stills by the shovelful. The essential oil obtained by this means was called patchouli vieille feuille or patchouli pays, to mark its difference from essential oil bought directly in Indonesia or Malaysia, which had a tough and tar-like consistency.

Depending on growing conditions, two or three patchouli harvests are possible in any given year. So long as there is no extended drought, the price of essential oil stays constant over time. Thanks to advances in distillation, grades of diverse quality are available. Among perfumers, an exasperating commonplace holds that using patchouli goes back to Chypre, created by François Coty in 1919. But people were using patchouli well before then.

It featured in Guerlain’s magnificent Chypre de Paris (1909), which is no longer commercially available, and also in the same firm’s Shalimar (although it’s not classified among Guerlain’s chypres). The term chypre began circulating even earlier. Guy de Maupassant’s 1890 correspondence with Maurice de Fleury, critic for Le Figaro, praises the perfumer Houbigant for “making it like no one else.” Since I don’t know Houbigant’s formula, I can’t confirm that this perfume incorporated patchouli. According to my modest research — factual documentation is sparse in the history of perfumery — chypre came into use in powders for hair and wigs in the 15th century. The products in question were scented with musk, civet, ambergris, oakmoss, rhizome of the so-called tiger nut (Cyperus esculentus, which has a violet scent), iris rhizomes, and sometimes labdanum; after being pulverized, these substances were combined with starch. Subsequently chypre came to refer to pomanders, “Cyprus birdies” (oyselets de Chypre), and potpourris before being made in liquid form. In the 18th century, the ingredients were joined by rose, orange blossom, jasmine, neroli (bitter orange), benzoin, tuberose, and bergamot — all mainstays of 20th-century perfumes.

In due course, patchouli entered the picture. Does chypre have a distinct “structure” in the same way that fougère perfumes or colognes do? I don’t think so. Chypre is the most controversial family in the trade, and this does not help classification. Patchouli isn’t necessary to create a chypre. Nor is labdanum, though perfumers use it widely.

A point that patchouli and labdanum share is a connection to goats: patchouli protects clothing made from the wool of the same goats that rub on the bushes that secrete labdanum resin — which people then collect. But that is another story.

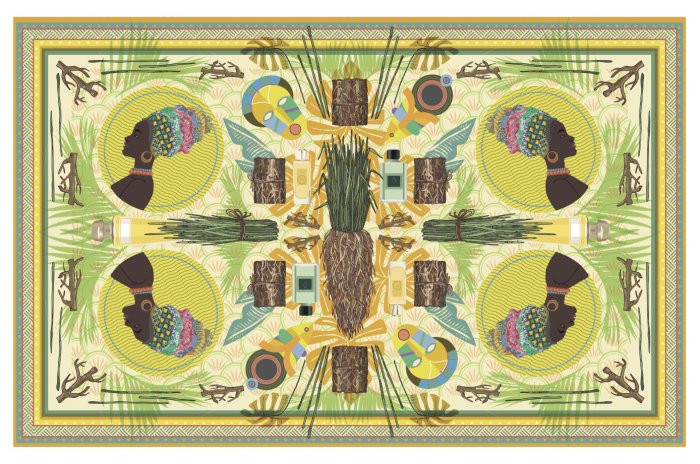

Vetiver

Chrysopagon zizanoides

Making new acquaintances always gives one a chance to add to one’s knowledge and learn about human life and how people live. On a trip to France in 2001, the First Lady of Mali had asked to meet a perfume maker. The consulates of the two countries conducted deliberations, and I was granted the honor of receiving the foreign dignitary. On a gray day in October, my guest arrived with two bodyguards in Grasse. Her traditional Malian dress was dazzling yellow with green braid sleeves. She was so tall and elegant that her beauty intimidated me. I invited her to visit the laboratory, but she declined. From the outset, she wished to discuss her passion for French perfumes and find out everything that goes into them. Intrigued, I asked about the role of perfume in Mali. The First Lady told me all about wusulan. This word refers to a fragrance, an object, as well as a method of scenting one’s body. A composition of oil, roots, resins, woods, and commercial perfumes is set on a burner (wusulan), which then is placed in a room where clothing has been hung to absorb the odor. It is also common practice for women to perfume themselves by standing in a bubu above the censer, so that the curls of fragrant smoke will impregnate their bodies and skin.

Among the elements employed, the most important is vetiver, the elixir of Malian erotic artistry.

Traditionally, the world of scent is reserved for the ladies, and each one has her own special recipe. The more complex and time-consuming the process, the better; it should take several days. Among the elements employed, the most important is vetiver, the elixir of Malian erotic artistry. Vetiver is credited with such wonder that wreaths of dried vetiver are boiled in water to obtain a potion, which women imbibe in great quantities so that their skin will release a subtle perfume during lovemaking. In the course of our conversation, I also learned that Habanita by Molinard, a fragrance invented in 1921, enjoyed particular popularity. Since perfume formulas are closely guarded secrets, Malian women could not have known that the composition contains more than 30 percent vetiver; their sense of smell did not lie. Just say “vetiver,” and you will hear that it is an odor for men. I always protest that this is not true; assigning a gender to a scent is an error in perfumery. Odors don’t have a gender any more than flowers do. French grammar makes the word jasmin masculine, whereas rose is feminine. The smells of these flowers — and of vetiver, too — are not masculine or feminine; it’s a shame that French doesn’t have a neuter gender.

To the best of my recollection, the first perfume for women to have contained vetiver is Habanita (1921); the scent has long enjoyed success not only in Mali but also in the United States (although I would not make bold to claim that the reasons are the same). A more recent fragrance, Calèche (1961) by Hermès, also includes a significant amount of vetiver. Guy Robert, its creator, enlisted the same principle he had used the previous year for Madame Rochas; the woody notes of vetiver and cypress give it gravity and austerity corresponding to Hermès brand: handsome feminine elegance. Vétiver (1959), the first perfume Jean-Paul Guerlain crafted — at the age of twenty — was intended for men.

This plant looks like a clump of tall, green grass without any particular charm. Its appeal lies in all that remains hidden, under the ground. Its deep roots help to maintain soil and combat erosion. Vetiver has long been grown on the island of Réunion, but it is also cultivated in Haiti and now in China. Three grades are produced. Oil from Réunion, or essential oil of bourbon vetiver, has a characteristic scent of matchstick and sulfur. Its Haitian counterpart is similar, but less opulent and lipid. Finally, vetiver essence from China has a distinct scent of potato, which is why it is not held in particularly high esteem.

In India, the dried roots are used for curtains that are moistened and placed in windows during the summer. As the air passes through them, it takes on the scent and freshens the room. Vetiver is also used to make fans and placemats; a few wisps will also aromatize drinking water — without any ulterior sexual motive.

Jean-Claude Ellena, the “nose” of the luxury brand Hermès for fourteen years, has been the Creative Director of Fragrance at the perfume house Le Couvent since 2019. He is the author of “Atlas of Perfumed Botany,” from which this article is excerpted.