Overdose, Police Science, and Lawrence Robinson's Legacy

On a chilly Los Angeles night in early February 1960, two narcotics officers pulled over a car with an unilluminated license plate moving slowly on a darkened street. Officers Lawrence Brown and S. T. Wapato were not traffic police, but were from the Los Angeles Police Department’s Wilshire Felony Unit. The officers inspected all four occupants’ arms and pupils with flashlights.

The green, four-door 1947 Nash was driven by its owner, Charles Banks, whose wife Norma occupied the passenger seat. A 25-year-old Black Army veteran, Lawrence Robinson, was in the back with a “lady friend.” Ordering Robinson to “bare his arms,” the officers noticed marks upon them and arrested him, classifying him a “vag addict,” or vagrant addict. They let the women go and took both men back to the station, where they were held without bail.

According to Los Angeles Deputy City Attorney William E. Doran, Robinson exhibited “a purported nervousness and perspiration” and, when asked, volunteered that he had used narcotics two weeks prior. At the time of the arrest, Robinson had no attorney and he appeared without counsel well into the proceedings. Another narcotics officer confirmed the marks on his arms as needle marks, and Robinson was charged with suspicion of being a narcotics user under California’s Health and Safety Code.

The judge instructed the jury that it “could convict Mr. Robinson even if it found no proof of actual use of narcotics by him[,] so long as it found him an addict.”

Arraigned on February 4, 1960, a jury convicted him of this offense on June 9, 1960. The jury was supplied with a magnifying glass to assure itself that the marks on his arms resulted from narcotic injections. The judge instructed the jury that it “could convict Mr. Robinson even if it found no proof of actual use of narcotics by him[,] so long as it found him an addict.” The jury was told that it did not need to disclose the basis of its decision to convict. Placed on probation for two years, the first three months of which he served in county jail, Robinson was required to submit to Nalline tests at whatever intervals probation required.

Detecting “Addiction”: The Nalline Test in the Police Precinct

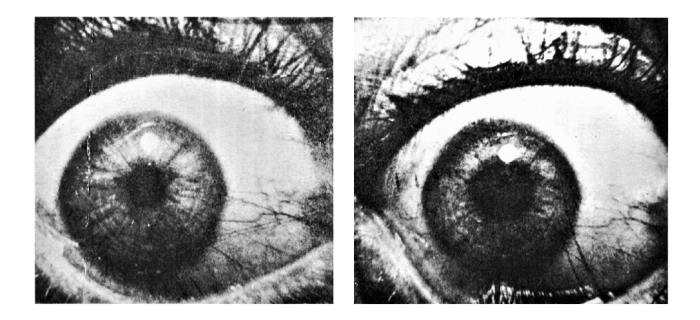

The Nalline test was the first diagnostic test for opioid addiction, accomplished by measuring changes in pupil size after a subcutaneous shot of nalorphine — a predecessor to naloxone, which makes resuscitation, rescue, and “reversal” after an overdose possible. Law enforcement officers used the test to surveil a broad population of potential addicts, deter casual drug users from becoming regulars, and control parolees and probationers. By the mid-1960s, law enforcement in Hong Kong, Singapore, and several U.S. states used it for a purpose not foreseen by scientists: to prevent people from falsely claiming to be addicted in order to obtain lenient treatment under state civil commitment laws.

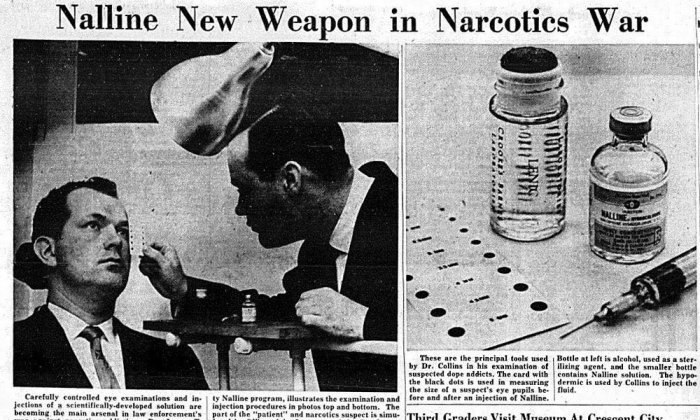

Although the Nalline test had been born in the laboratory, implementing a simplified version of it in the Oakland police precinct was an idea thought up by Alameda County medical officer James Terry, who claimed to have been inspired by an encounter with an “unknown pretty girl” whose pupils he had observed dilate after her first shot. A physician working in criminal justice, Terry standardized dosage and a technique for measuring pupil size, as described in a 1961 book called “The Enigma of Drug Addiction,” authored by another of the Nalline program’s chief architects and defenders, Thorvald Brown, Commanding Officer of the Vice and Narcotic Division. Captain Brown was one of the primary advocates in the national press for adopting Nalline as a tool of antinarcotics policing. He was nothing if not energetic about public relations; newspaper coverage of the program reached throughout the country.

Nalorphine, however, intensified the unpleasant symptoms of abstinence. Its accuracy depended on the timing, dosage, and level of the subject’s tolerance. The laboratory was not the field; in the laboratory, morphine and nalorphine dosages could be precisely calibrated. Negative tests sometimes occurred if other drugs were present, yet law enforcement considered the test definitive; there are hints as well that it was used in a punitive way to end heroin’s “kick.”

No simple antagonist, Nalline’s subjective effects varied: It made some people feel drowsy like alcohol, barbiturates, or small doses of morphine do. Others were plagued with vividly disturbing daydreams or visual hallucinations. Higher doses produced unpleasant anxiety or thoughts that raced uncontrollably. Administered soon after morphine, subjects nicknamed it “Climalene,” named after a commercial cleaning fluid that “cleans you out of dope and makes you climb the walls.” Nalorphine’s discontents were represented as the stark opposite of heroin. How could such a motile technology have found a decades-long niche as a supposedly standardized assay in police hands?

Police detailed to narcotics investigations were enthusiastic about the Nalline test. The Federal Bureau of Narcotics urged local law enforcement to adopt this tool of “scientific policing,” and California cities, including Eureka, Fresno, Los Angeles, Oakland, Sacramento, San Francisco, and Stockton, had done so by the early 1960s. Increasing heroin use in the 1950s led California legislators to criminalize both the act of consuming narcotics and the condition of being addicted to them. Those convicted under the 1954 amendments to the Health and Safety Code could be sentenced to the county jail for 90 days to one year.

Police in Alameda County instituted an elaborate Nalline testing program in 1956. The former chief of the Oakland Police Department, Wyman W. Vernon, was, according to Brown, the first law enforcement administrator to foresee the value of this test for moving drug users toward treatment. Police were thus positioned on the side of treatment, and civil liberties laws and legal safeguards appeared as barriers to it. The Oakland Vice Squad formed a Narcotic Detail that worked closely with Terry, who was the medical officer of a facility located in the Oakland foothills and variously known as the Alameda County Jail, a county prison farm, the Alameda County Sheriff’s Rehabilitation Center, and the Santa Rita Rehabilitation Center — all names referring to the same facility.

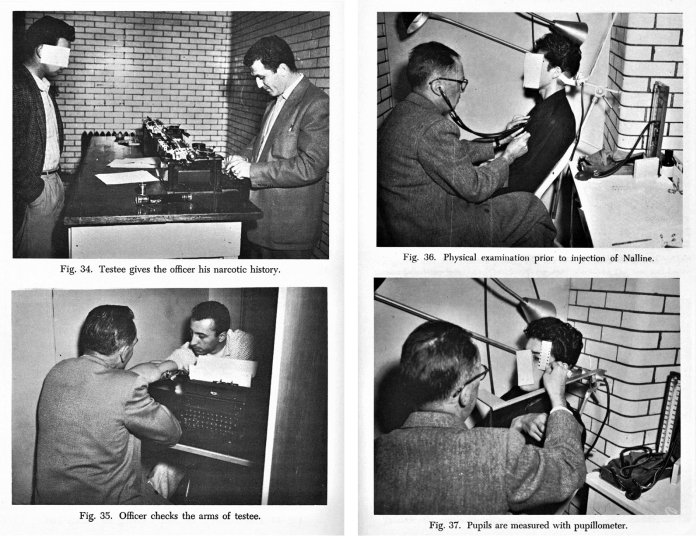

The first in the nation, the Oakland Nalline Program served as a model for other cities, counties, and states desiring to use nalorphine as a detection device. Program administrators fielded inquiries from Chicago, Detroit, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Texas, and received official delegations from “Arabia,” India, Iran, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Nalorphine was inexpensive and easily obtained, but its symbolic politics were also important: Control over an unruly population was mentioned as an advantage of the technology. The goal, according to Brown, was to “detect and isolate those who have been using narcotics so that enforced abstinence and treatment can be provided and control measures instigated.” His book included sample forms associated with authorization and release of results. Numerous photographs showed him examining suspected users for track marks. Also pictured were the equipment and setup used to position the “testee.”

Depictions of track marks, sclerotic veins, and crude tattoos used “in a feeble attempt to hide the tell-tale scars,” as Brown writes in his book, indicated that the Vice Squad was apparently in the habit of photographing injection sites and labeling each with a typed identification number and date affixed to the body part with transparent tape. Such photographs testify to the extent of police scrutiny into addict embodiment in the course of the project to “rehabilitate” the addicts of Alameda County.

Police participation in “therapeutic” procedures imparted the status of science and medicine to police and probation officers, which many appeared to embrace as a form of professionalization.

Indeed, Captain Brown presented Nalline as giving police the leverage of a “therapeutic crutch.” Police participation in “therapeutic” procedures imparted the status of science and medicine to police and probation officers, which many appeared to embrace as a form of professionalization. Later critics of the program pointed out that a “rhetoric of rehabilitation” affected Oakland police to such a degree that officers felt it “part of their business to change and ‘cure’ drug users as well as to merely catch them.”

Along with the “vigilance of local peace officers,” the Nalline program was credited with heroically driving heroin traffic out of Alameda County. Objections to the test issued from a few quarters, most notably drug users themselves. Although few consulted users about their perspectives, one quoted in the news dismissed the test as easy to beat — “Look, man, you don’t fix before you go in for your test, you go out and fix AFTER the test.” Legislators in New York State declined to use the test because they saw it as a “chemical superego” or “artificial will,” talk that Brown found preposterous because an addict was “likely to need as much in the way of his own resources as he can bring to any problem, rather than a chemical conscience.” The debate over the social utility of inducing or strengthening an “artificial will” by “substituting” a drug for a conscience or superego later surfaced in struggles over methadone maintenance.

The Nalline clinic made assumptions about the moral purpose of law enforcement, constant surveillance as a basis for rehabilitation, and the advantages of quasi-scientific production of evidence for use in criminal proceedings. The ultimate goal of the Nalline clinic was to reduce drug-related crime, but it enabled police to constitute themselves as scientific experts who could be useful in courts of law, where rules of evidence played a regulatory function.

Although Nalline clinics phased out in the 1970s, the test remained admissible in the most recent edition of Jefferson’s “California Evidence Benchbook.” As a “chemical superego,” nalorphine died a slow death. Positioned as both relapse prevention and deterrent, it was never used to reverse overdose outside of hospital settings such as operating rooms and emergency rooms.

Lawrence Robinson’s Legacy

By the time he was released, Robinson’s mother had engaged a lawyer, Samuel Carter McMorris, to argue her son’s case. He did so — all the way up to the U.S. Supreme Court. The case is considered a watershed precedent — not on Fourth Amendment rights to be free from illegal search and seizure, but on Eighth Amendment rights to be free of cruel and unusual punishment.

Confused, prolix, and scattershot in oral arguments, McMorris’s most coherent point was that “any statute which punishes a status as distinguished from an act or omission is unconstitutional.” He argued Robinson had been convicted on grounds of “suspicion itself” — the suspicion that he was an addict, a “wholly involuntary status.” He argued that

an addict no more intended to become that than does an alcoholic intend to become an alcoholic because he may have liked to drink socially.… [A] person intends to take a drink, intends perhaps to take [a] shot of heroin or smoke a marijuana cigarette or intends to have an illicit sex act. None of these intended to acquire venereal disease or to become an alcoholic or to become an addict.… No one, I submit, intends to become an addict.

Advocating treatment and not punishment, McMorris dismissed the California Health and Safety Code as “vague, indefinite, and uncertain,” because the term “addict” referred, firstly, to mere use of the drug; secondly, to being “under the influence”; and thirdly, to being “addicted to a narcotic.” According to McMorris, only those using narcotics out of compulsion and only those whose bodies and physiological functions were clearly “disorganized” by drug use should be considered addicts. Throughout, he implied that this was not Lawrence Robinson’s situation.

Pointing to the suffering entailed in “cold turkey California penal treatment,” McMorris stated that “terrible violent withdrawal[s]” in jail had led to deaths of which he was personally aware. Claiming great experience with narcotics, he pointed to the dangers of collapse and death due to withdrawal. Cold turkey, argued McMorris, was “cruel and unusual punishment for the condition of addiction.” The justices specifically asked McMorris whether he had experienced cases of “double jeopardy,” where individuals were prosecuted multiple times for “the same addiction,” to which McMorris exclaimed, “Every day. It’s constant.” He accused police of punishing any “evidence of continued use.”

Cold turkey, argued Robinson’s lawyer, was “cruel and unusual punishment for the condition of addiction.”

Gaining little traction, he was directed to pursue the constitutional questions that his exhausted appeals at the state level had placed before the court. The very last question that Justice Earl Warren posed to the hapless lawyer was whether his client was still on probation. McMorris assured the Supreme Court that his client remained on probation and subject to the Nalline testing program.

McMorris was an unlikely champion of the rights of drug users. While preparing for the Robinson case, he took a night course in criminology. At one class, a guest speaker — an “expert from the LAPD narcotics squad” — mentioned that marijuana was not considered a narcotic, and in response McMorris wrote a paper titled “What Price Euphoria? The Case against Marijuana.” He argued that if the U.S. government did not ban marijuana, LSD, and other substances causing “temporary insanity,” “we shall find ourselves at the threshold of that day in our history at which the American dream will evaporate into a nightmare of generally self-imposed narcotic insanity, from which there will be no return.” Viewing drug use as a form of brain damage comparable to insanity, McMorris distinguished involuntary mental illness from voluntary acts under intentional control.

Yet civil commitment of drug addicts was precisely what the State of California had inaugurated in 1961 (followed shortly thereafter by New York State’s Narcotic Addict Control Commission and in 1966 by the federal government’s Narcotic Addict Rehabilitation Act). Under the guise of a therapeutic regime premised on civil commitment, the California program placed restrictions so severe they might be thought of as punishing.

The U.S. Supreme Court’s 1962 decision was heralded beneath such headlines as “Drug Addiction Ruled No Crime.” Commentators on the implications of Robinson v. California noted the Court’s willingness to “set its face against those who are content to imprison the addict and not to cure the disease.” The goal, according to one law review article, was “a modern, civil and successful treatment of this sad, sick segment of our people.”

The decision was understood as a watershed in the decriminalization of so-called victimless status crimes. One effect was to disallow California’s unusual statutes and court decisions enabling conviction without proof that defendants had used, purchased, or possessed illegal narcotics at the time of the arrest. Although the Supreme Court invoked the Eighth Amendment’s “cruel and unusual punishment” clause, Justice Harlan White’s dissent chided his colleagues for making a strained attempt to write into the Constitution their “own abstract notions about how best to handle the narcotics problem.” The majority opinion, authored by Justice Potter Stewart, still reads as a liberal call to arms, despite its affirmation that states might confine addicts indefinitely for “compulsory treatment, involving quarantine, confinement, or sequestration” for therapeutic purposes. The majority wrote, “It is unlikely that any state at this moment in history would attempt to make it a criminal offense for a person to be mentally ill, or a leper, or to be afflicted with a venereal disease.… Even one day in prison would be a cruel and unusual punishment for the ‘crime’ of having a common cold.”

But Lawrence Robinson had neither leprosy nor a common cold. Nor had he found Nalline tests either deterrent or therapeutic. He had been found dead in a Los Angeles alley of a “probable” overdose on August 5, 1961 — fully 10 months before the Supreme Court rendered its opinion. His lawyer had either given a very credible performance of not knowing that his client was dead, or was genuinely unaware of that cold fact. Once it came to light, California’s attorney general filed a petition requesting that the decision be vacated and all proceedings rendered moot by Robinson’s death. The Supreme Court denied the petition and thus Lawrence Robinson’s name lived on, invoked as a liberal bellwether in the decriminalization of “status crimes” or “crimes of condition.”

Nancy Campbell is Professor and Head of the Department of Science and Technology Studies at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. She is the author of, among other books, “OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose,” from which this article is adapted.