Formless, Faceless, Directionless: Earthworms Defy Architectural Logic

Architects do not draw earthworms; they are a disturbing affront to the very notion of form. Modular and iterative, their repeating rings could have been the envy of modernist and organicist experimental architects.

But no, there is no reference to worms of any sort in, say, Le Corbusier’s Plan Obus for Algiers, which proposed running a motorway atop a long ribbon of social housing. Nor was there any mention of worms in relation to Luigi Carlo Daneri’s INA-Casa Forte Quezzi complex in Genoa. Instead, Daneri’s project — known for its long, linear undulations along the slope of the Quezzi valley — was nicknamed “Biscione,” or the big grass snake.

Of course, the earthworm does possess a kind of rudimentary form — a head and a tail. But it is exceedingly difficult to tell its mouth and anus apart at first glance. Architecture likes consistency: fronts and backs, beginnings and ends. The earthworm questions that binary. It is oblivious to the vertical and the horizontal, the surface and the ground, boundaries which it disturbs as it stirs, digests, and mixes soils.

Architecture likes consistency: fronts and backs, beginnings and ends. The earthworm questions that binary.

For architecture, all of this raises a profound ontological problem — and thus, a threat. Philosopher Georges Bataille claimed that the earthworm (along with the spider and spit) is the epitome of the formless (informe), something that “has no rights in any sense and gets itself squashed everywhere.” The formless, Yve-Alain Bois likewise argued, must be crushed “because it does not make any sense, and because that in itself is unbearable to reason,” adding it is “the unassimilable waste that Bataille would shortly designate as the object of heterology.”

Georges Didi-Huberman, on the other hand, gave the earthworm a bit more credit: Examining it through the lens of “formless resemblance” (ressemblance informe), he suggested that the worm contains an embedded figure, morphology, and metaphor. Yet Bois contended that the informe is simply “not referring to a resemblance but to an operation.” The informe, then, is not a figure but an operation that “crushes metaphor, figure, theme, morphology, meaning everything that resembles something.”

The unsettling operation of worms is something science realized a long time ago. Drawing on observations by Charles Darwin and Otto August Mangold, Jakob von Uexküll explains that the earthworm identifies different parts of a leaf or a pine needle — not by shape but by taste. There is “nothing to the notion of shape perception in earthworms,” Uexküll concluded. “The worm is in no condition, by its constitution, to develop shape schemata,” and it is the change in taste that becomes the “form symbol for the earthworm.”

Indeed, no shapes for the earthworm, which smells and tastes and operates by moving matter around and through its own body. If anything, it is this that the architect can grasp and represent. The traces left behind/around by the earthworm are not only the marks of its movements and the spaces of its making, but the product of the transformation of the soil it performs: the transferring, the processing, and the digestion of matter.

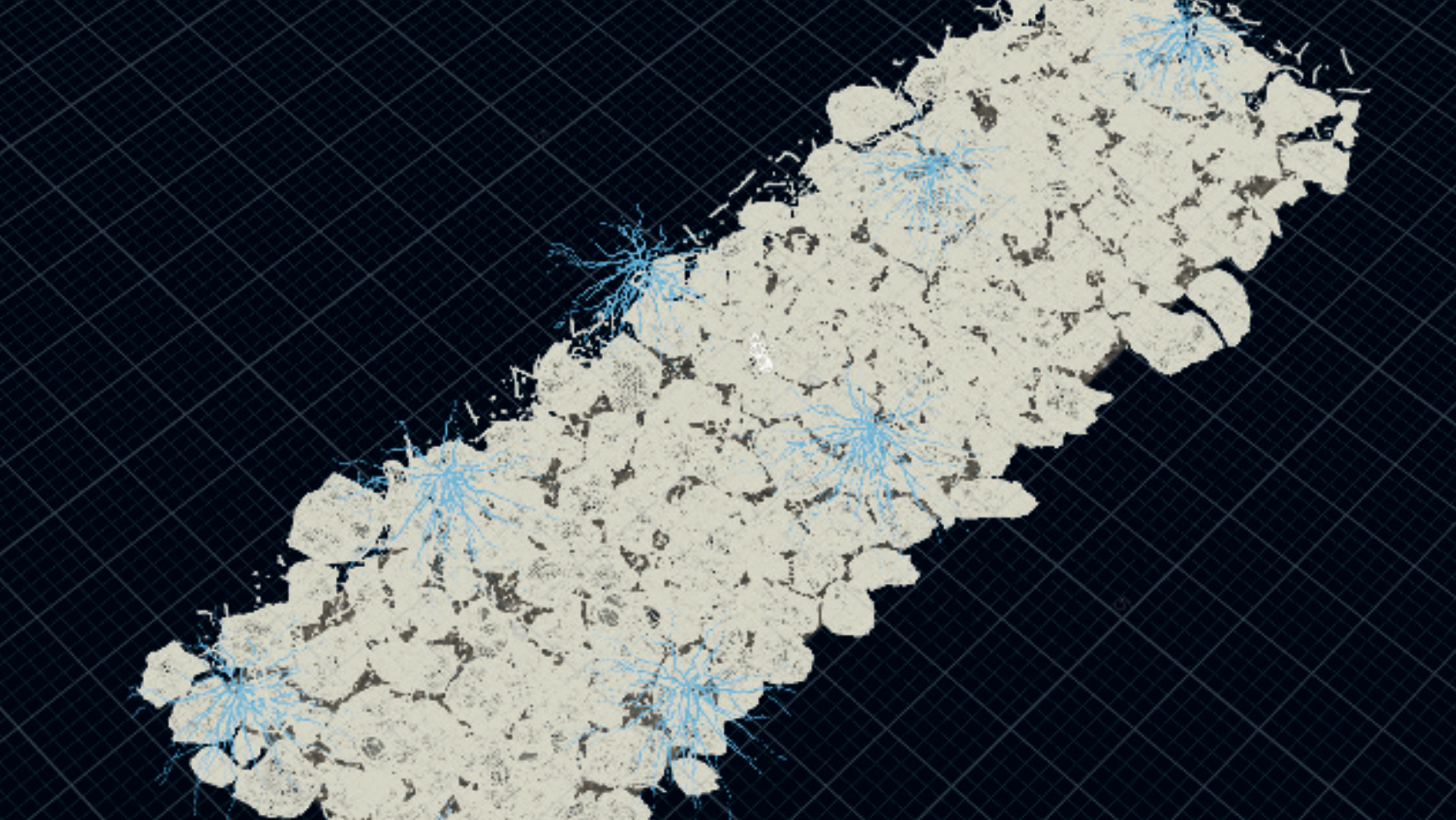

Consider “The Nebelivka Hypothesis,” a collaboration between Forensic Architecture and archaeologist David Wengrow in 2023. Their research project, which focused in part on the village of Nebelivka, spread across a wide area of the Ukrainian steppe to explore the traces of 6,000-year-old settlements. The team used the earthworm’s traces as an investigative clue and discovered that it had been a co-constructor of the rich substratum that sustained ancient communities and is now the fertile black soil of central Ukraine.

Their investigation combined archaeology, paleobotany, and soil science with the tools of Forensic Architecture (aerial photography, satellite imagery, image processing, electromagnetic scanning, remote sensing, multispectral dataset analysis, and parametric modeling). Taken together, these disciplines revealed the subterranean remains of cities “organized as concentric rings of domestic buildings, around a mysterious open space” that remains empty. The remains of these large ring-shaped settlements appear to be centerless, and show “no traces of temples, palaces, administration, rich burials, nor any other signs of centralized control or social stratification.”

The findings of “The Nebelivka Hypothesis” propose something extraordinary: the existence of an ancient urban settlement sustained not by hierarchy or centralization but collaboration. Yet the project’s most striking finding emerged beneath the ground: Researchers discovered that the soil’s “architecture” was built on chernozem, an anthropogenic soil (anthrosol) produced by humans in collaboration with earthworms. This process began with the “sacrificial” burning of houses in the settlement’s innermost concentric rings; their reduction to compressed platforms of incinerated wattle and daub provided the ideal environment for earthworms, which in turn helped create nutrient-rich soil for agriculture.

Soil becomes an artifact and the artifact becomes an extension of the soil.

“The Nebelivka Hypothesis” not only challenges the hierarchical and extractive nature of the city’s relation to “its” territory but also proposes a productive collaboration of human and nonhuman (buildings, fire, earthworm, soil) agents in the making and maintaining of the environment: “Soil becomes an artifact and the artifact becomes an extension of the soil.”

There are many wormlike critters in John Hejduk’s architectural parables, but they are not earthworms. Rather, they are serpents, tentacles, Medusa’s mane, even unruly garden hedges, all performing the architectural detours that Hejduk so wonderfully stages. Curiously, however, there are worms in his illustration of Aesop’s fable, “The Hare and the Tortoise,” accompanying the tortoise to the finish line. But they are fable earthworms: They have a crowned head, eyes, and a smile, even if they do not have a mouth. Or maybe they are victoriously mocking us, as one of them cements the moral of the fable. Slow and steady wins the race.

Professor Teresa Stoppani is the Director of Architecture and Interior Design at Norwich University of the Arts. An architect, architectural theorist, and critic, she lectures in history and theory and teaches design studio across various disciplines. One of her essays was published in Kostas Tsiambaos’ book, “The Architect and the Animal,” from which this article is adapted.