What Designers Can Learn from Magic Realism

As Mark Twain remarked in “Following the Equator,” “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; Truth isn’t.”

When an idea or scenario is presented as a future, there is a natural impulse for people to think about how to get from here to there, triggering all sorts of pragmatic and limited conversations. It is evaluated against plausibility. Or it is taken literally as a wish, desire, prediction, or prescription to be imposed by one group of people on another.

At a time when “futures” have become the dominant mode of framing the “not here, not now,” at least in design, magic realism might allow us to move beyond the limitations that condemn designers, including us, to forever reimagining variations on a broken reality. It can reveal pathways that lead beyond the projection of objective realities grounded in science and technology to a far larger, richer landscape influenced by literature, philosophy, and art. Unconstrained by “technological reason,” it offers something a little more poetic, which if you are trying to prompt new thinking rather than provide options, seems like a good direction to explore.

It also gently signals that a project is not “real,” avoiding the kind of confusion that arises when the unreal is presented as real. With magic realism, the unreal is only ever presented as unreal, whereas fake reality is unreality pretending to be real. In design especially, viewers often take the potential of something to be real for actual reality. Some designers declare this, while others hide it.

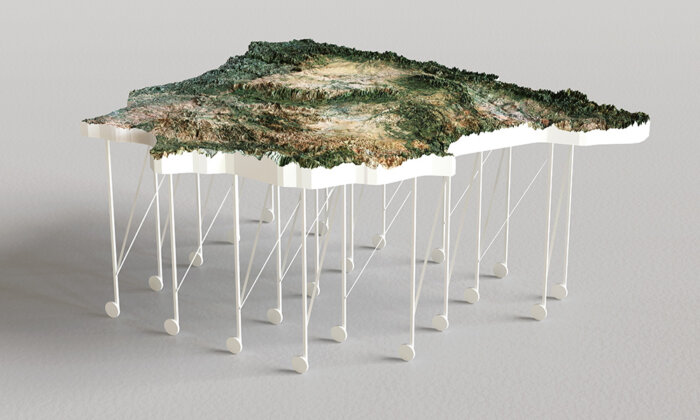

With magic realism, there is no need to leave this world or travel to the edges of the universe in search of novel ideas. In this form of world-building, small but significant adjustments are made to the world we already live in. Often unexplained and free from scientific justification, they celebrate and highlight boundaries between the real and the unreal. Things happen that could never happen in our reality, but nonetheless people carry on, only mildly disturbed. In José Saramago’s “The Stone Raft” (1986), the Iberian Peninsula breaks away from the continent of Europe and begins to slowly drift across the Atlantic Ocean, becoming the setting for a political fable.

With magic realism, there is no need to leave this world or travel to the edges of the universe in search of novel ideas.

As designers, could we embrace and make use of strategies like this? Such magical realist worlds might be impossible, but they are not pointless. They can serve as a stage or setting for helpfully decontextualized alternative realities.

In Saramago’s “Stone Raft,” life carries on. The characters’ reactions to the event are pragmatic; everything else in the world in which the apparently impossible thing has happened appears normal or as we would expect. The result feels absurd. Magic realism usually makes no attempt to explain or justify the anomaly behind the magical event. Its justification lies in the conceptual possibilities it allows for in the narrative, pleasure it provides, and feeling of strangeness that comes from a familiar world being tweaked. Bringing magic realism to design has always felt a bit uncomfortable, almost too easy, but we’re not so sure anymore.

This tension between rational and ungrounded speculation in relation to literature is something science fiction theorist Darko Suvin has grappled with in several of his writings. For Suvin, science fiction is “a literary genre whose necessary and sufficient conditions are the presence and interaction of estrangement and cognition, and whose main formal device is an imaginative framework alternative to the author’s empirical environment.” He suggests there is a spectrum with naturalistic worlds at one end — that is, worlds that resemble those of the author and reader — and at the other, invented worlds — what he terms “novum”— that generate defamiliarization, or what he calls “cognitive estrangement.” This is what separates critical science fiction from fantasy, which may be inventive and pleasing, but lacks a critical dimension:

The folktale also doubts the laws of the author’s empirical world, but it escapes out of its horizons and into a closed collateral world indifferent to cognitive possibilities. It does not use imagination as a means of understanding the tendencies latent in reality, but as an end sufficient unto itself and cut off from the real contingencies … It simply posits another world beside yours where some carpets do, magically, fly, and some paupers do, magically, become princes, and into which you cross purely by an act of faith and fancy. Anything is possible in a folktale, because a folktale is manifestly impossible.

Although later, in the 2000s, reflecting on how times had changed since the 1970s, he begins to question this: “Let me therefore revoke, probably to general regret, my blanket rejection of fantastic fiction. The divide between cognitive (pleasantly useful) and non-cognitive (useless) does not run between SF and fantastic fiction but inside each — though in rather different ways and in different proportions, for there are more obstacles to liberating cognition in the latter.”

“The Stone Raft” can be viewed as a stage or setting rather than a scenario. It provides a framework that estranges on a larger scale. Is it finally time to look to magic realism as a way of moving beyond the coziness of futures thinking in design, produced by following extrapolative threads tied to existing reality? This is something that has long been explored by artists and designers interested in Afrofuturism and its many variations, but for those of us trapped within a tradition of scientifically grounded speculation like science fiction, this leap is more difficult to make.

Magic realism could offer pathways forward that leave behind the problem of reproducing existing mindsets through material and visual reification. Allowing us instead to constructively undermine them, creating room for new possibilities and imaginaries to emerge. Once we leave behind the overly rational that defines much of Western speculative fiction in design, many other forms of speculation begin to emerge. Moving from questions of “How do we get from here to there?” or “Is it plausible?” to ones of “Is it interesting, and what new thoughts does it make possible?”

Maybe as designers, we could embrace a remark Borges made during a lecture on poetry he gave at Harvard in the 1960s. He claimed that no argument ever convinces, as we immediately respond with a counterargument that challenges, unpicks, and tests it. Whereas something hinted at, such as through metaphor, engages us differently and enters the imagination more easily. Not to convince as such, but to exist within the mind.

Anthony Dunne and Fiona Raby teach at The New School/Parsons in New York. They are the authors of “Speculative Everything” and “Not Here, Not Now,” from which this article is excerpted.