The Year When Pregnancy Was a Fashion Statement

In her 1979 memoir, the novelist Naomi Mitchison writes about dressing up and its decline since the 1930s as collateral damage in the move to “the present idea that anything goes, so we can always and everywhere be in fancy dress.” It’s mostly true now, too, that anything goes. You have to go all out at fancy-dress parties to make it clear you’re dressed up.

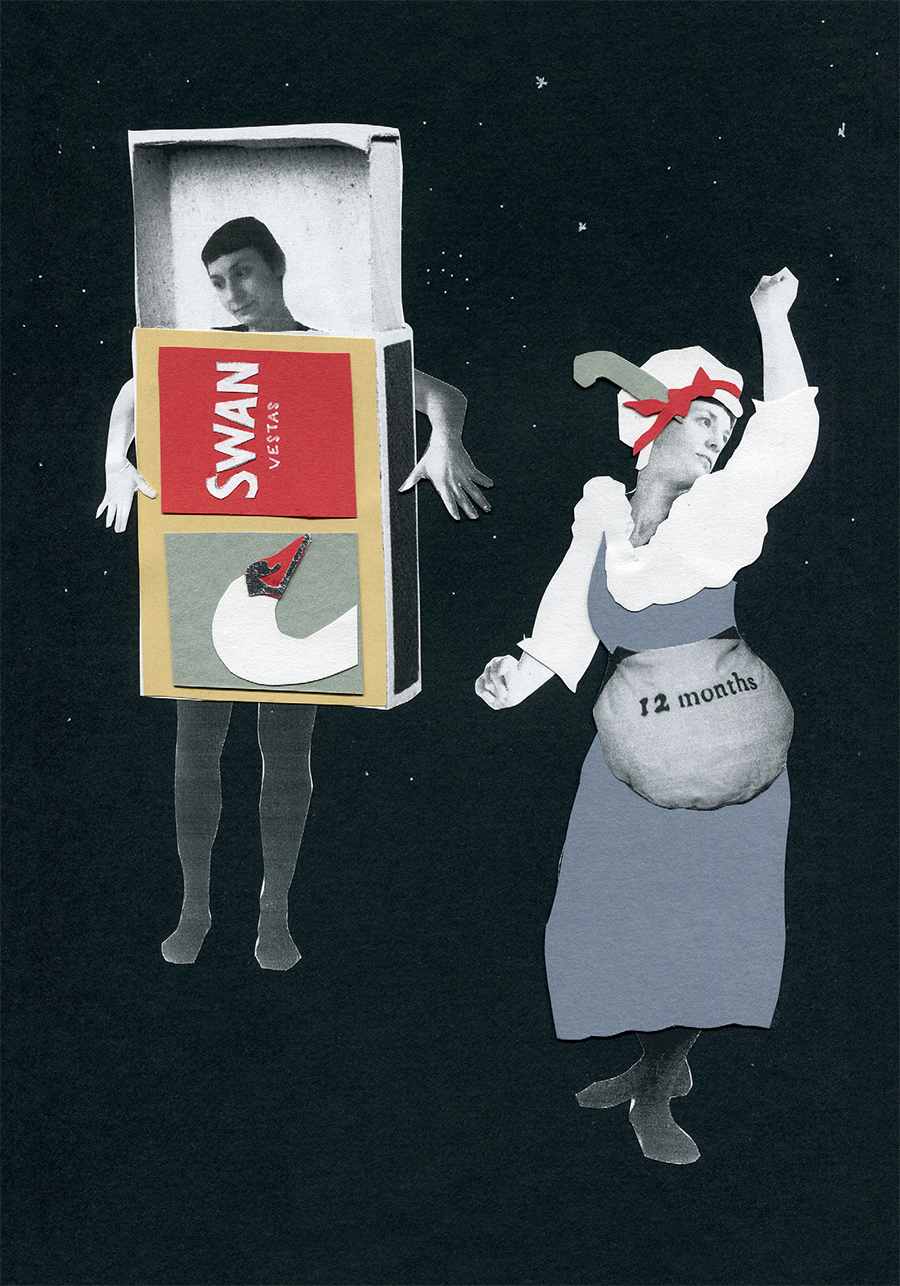

Going all out, I once tried to go to a fancy-dress party as a Swan Vesta matchbox, wearing an elaborate cardboard contraption painted with a lot of time and effort. The party turned out to be on a roof that could be accessed only through a window too small to fit the matchbox. So I went to the party wearing the clothes I had on underneath the costume.

“What have you come as?”

“Um, as an invisible matchbox? Can’t you see?”

It’s true, lots of things “go” but still not quite everything. Mitchison overstates it. Haute couture catwalks couldn’t show unwearable fashion if everything “went.” It’s mostly not acceptable to go about daily life dressed as a matchbox or wearing a bird’s nest, rubbish, or lobster claws on one’s head, even if it is designed by Dior. And for those who aren’t pregnant, bump-baring maternity wear is currently unavailable. In the 1930s, Mitchison remembers, “pretty maternity dresses” ended up “in the acting box.” Yet even now, maternity wear is strictly for pregnancy or let’s pretend.

There was one amazing year, though, 1793, when the pregnant look did “go” and anyone could wear it. You could buy a false bump called The Pad and wear it under a flouncy dress with a push-up cleavage. London’s Morning Herald newspaper notes that “Pads continue to be worn; and on account of these the dress is still a loose gown of white muslin flounced in front, appearing to be put on with the negligence permitted to the supposed situation of the wearers. A narrow sash ties it at the waist.” This wasn’t quite the little white empire-line muslin dress familiar from Jane Austen costume dramas, but it was heading that way from the exoskeleton corsetry of the ancienne régime. You could put on this pregnant outfit and walk around the fashionable districts of town.

The 21st century has seen a trend for pads, fillers, and surgery to enlarge lips, breasts, and buttocks, but we don’t yet have off-the-peg belly pads as they did in 1793. Celebrity gossip keeps a close eye on body fakery. Has she or hasn’t she had her nose, breasts, bum done? The charge of feigning pregnancy has an edge that allegations of other cosmetic enhancements do not. Meghan Markle, Beyoncé Knowles, Katie Holmes, and others have been suspected of faking pregnancies. These duplicitous celebrities, so the rumor mill grinds, have hired mysterious surrogates to do their gestating work. Suspiciously, a dress folds in the wrong place, a bump is too low or high or slips down, a shadow looks photoshopped to hide the join of a prosthetic bump. The bloggers and columnists, clickbait news sites, and social media influencers promise forensic detail: the way clothes move, the anatomy of the pregnant body, the tone of her denials, the baby’s resemblances. The fear is that celebrity women are winning fraudulent membership in the sacred motherhood club whilst holding on to the perfect bodies which real mothers are prepared to sacrifice on entry. Who is and isn’t in the club is policed.

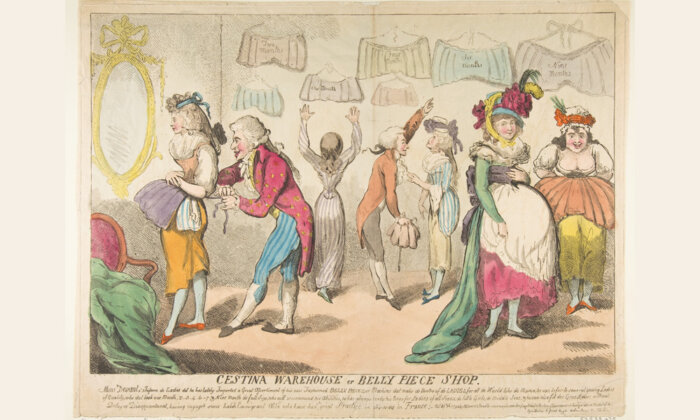

The 18th-century fashion for The Pad began at the point at which we stop, with the padded bum, being preceded by a much longer-lived fashion for the bustle. A cartoon from 1785 called The Bum Shop shows women buying petticoats with built-in bustlers (segmented pouf-like pads) to extend the dress at the back. Several pads hang on the walls, and others are piled on the floor. One woman sits grinning idiotically at a huge, puffed-up pillow on her lap. Others are being helped by two attentive salesmen. The bustles underpin the distinctive chemise à la reine that was popularized by fashion icon Marie Antoinette, with its cloud of white ruffles around a low neckline, sashed at the waist. A poodle, coifed to make pompoms of its torso and tail, stands on its hindlegs: puffed, ruffed and bum-padded, just like the ladies being fitted for bums.

But then, the bon ton, not content with padding only bums, moved the bustle round to the tummy at the front. And once it got there, it took on more meaning than it had as a bum pad because now it simulated pregnancy. Contemporary commentators are clear that that was the intent. A 1793 cartoon designed to imitate The Bum Shop called The Cestina Warehouse or the Belly Piece Shop shows two salesmen attending women who are shopping for tummy pads. The words at the bottom of the cartoon voice the assistants’ sales patter in heavily accented French (all the silliest fashions come from France). The pads hanging on the wall or already strapped onto customers are marked up with gestational ages: two months, six months, or twins. One padded woman looks out grinning, enjoying the jest. Another is presumably padded, but her closed lips form a smug and knowing smile, a hand over her bump dotingly, as if to say, “Who knows?” Behind them, a slim figure reaches up on tiptoes, but the one-month pad is still out of her reach. I know the feeling.

Unbelted tents (systematic cover-up) have been more usual in the history of Western maternity clothes. When corsetry was in, expander panels conceded space, but often pregnancy was too rude and ugly to be revealed with a defining belt or sash. The advice in Vogue in June 1930 is about how to pass as not pregnant:

At first, complete concealment is easily effected by any woman with an eye for dress, but, after the figure is obviously changed, it is still possible to achieve, sometimes to the very end, the effect of a normal figure. Not one’s own figure, to be sure, and thicker than one might wish. But, still, one may look to the casual observer like thousands of others that pass on the streets.

Yet there are points in history when pregnancy gets a makeover and gathers enough cultural cachet that the bump can be flaunted. Indeed, The Pad demonstrates that there were times when the preference was effectively reversed: Not only that the pregnant were happy to admit to it but that the not-pregnant sought to look pregnant, too. Looking back to the padded-out pregnancy look of the late 18th century, the 19th-century physician Thomas Tanner (1824–1871) saw it as a political gesture that emerged in relation to the French Revolution: After the first French Revolution there was a great cry about patriotism, and the need of children for the Republic. Hence, those Parisian ladies who were fortunately enceinte [pregnant], made the greatest possible display of their condition; while such as were less happily situated, invented a style of dress which should at least give them the reputation of being as they vainly desired to be.

Only in the crazy year of The Pad could everyone try on pregnancy for size.

Historian Leslie Tuttle has described a “pronatalism” dominating political and cultural ideology in early modern France, which brought with it a powerful emphasis on marriage, the family, and sex positivity. Across the channel, an English ballad contemporary to The Pad also suggests that padded fashion victims pretended not just to pregnancy but also to patriotism:

Had I really not known This odd taste of the town;

I’d have thought ladies gone very far, And have laid any bet,

All the women I met

Were raising recruits for the war

The war here is the Napoleonic War with France. Historian Lisa Forman Cody corroborates the idea that pregnancy was beautified as an English patriotic endeavor at the end of the 18th century: “patriots beat the drum most loudly for building a hearty population against the French menace.” Pregnancy was flag-waving, and padding up was a travesty. Some historians have suggested that The Pad fits with the fashion for natural, even eroticized motherhood, with an emphasis on the breast and maternal breastfeeding, although in simulating pregnancy, it looks less about getting back to nature than being anarchic and playful with those trends.

The Pad was lambasted in the print-shop windows where caricaturists laid into all the ludicrous fashions: bums, breasts, bellies, skirts, hats, and hair. If, in 1793, you were going to visit the full-scale model of the guillotine exhibited at S. W. Fores’s Piccadilly print shop, you could hardly miss these merciless cartoons. Marie Antoinette would be executed in October of the same year; French fashion influence was a sign of an effete aristocracy that was potentially losing its grip. The satirical prints let you know that you might see The Pad worn in the fashionable streets of London’s West End, modelled by the glitterati around the Prince of Wales near St. James’s Palace and other celebrity hangouts.

A cartoon by Isaac Cruikshank, Frailties of Fashion, shows just such a scene, with the prince arm in arm with his long-term mistress, Mrs. Fitzherbert, and the diminutive Duchess of York; both women are padded. In the middle are two young society beauties wearing the new clingy fashions with uncaricatured style, but amongst the mixed-sex groups that mill around them are gratuitously padded older women. Low necklines with floppy white collars plunge to rising abdomens. Several of the figures rest a self-satisfied hand at the apex of their bump. The bumps push out candy-striped and aproned gowns; they are exaggerated by belted waists, and one particularly protuberant tummy doubles as a perch for a parakeet.

Medieval belts also managed a celebration of the pregnant silhouette, but devotion to Mary rather than patriotic “populationism” legitimized it. Mary, as an icon of virginity, broke a conceptual link between sex and conception, making it morally all right or even pious to sport a bump. That link has been severed for us, too, and pregnancy made less sexually suggestive than it was in the past by innovations in contraception and particularly the pill. Once sex could be enjoyed with less risk of pregnancy and once pregnancy could be more readily planned, sex that resulted in pregnancy took on a more pious character in moral opinion.

Mary, as an icon of virginity, broke a conceptual link between sex and conception, making it morally all right or even pious to sport a bump.

This purification of pregnancy has seen maternity fashions exploit the full potential of spandex, belts, and bows to annunciate rather than conceal the baby bump. Even bridal wear can be in on the act, with pregnancies “showcased even as women walk down the aisle.” Bridalwear shops have moved from concealing sexual shame to articulating pregnant pride. Since Demi Moore’s famous 1991 cover for Vanity Fair where she posed naked at seven months pregnant, we have steadily recovered from the shock at seeing the pregnant body celebrated in fashion shoots and celebrity images. The naked bump is the ultimate in maternity wear. Maternity wear is part of our wear-once fast-fashion culture, but nakedness pretends to timelessness. These are images which evoke nature as a force at apparent odds with fashion, holy versus unholy.

Pregnancy can be privatizing, and it is fitting that it registers in conspicuous consumption. Conceited and smug are words that look as if they were made for the pride brought on by pregnancy. Conceit has the same root as conception, a word with a dual role: a mental image or an idea and the beginning of pregnancy. Conceitedness about anything is being full of ideas of self, inflated with pride, pregnant or padded with it. Conceitedness about pregnancy is as appropriate a relationship between word and meaning as a fetus, all curled up, in the womb. Smug, as we use it as a synonym for conceited or self-righteous, emerged from its earlier sense of “neat and trim,” which is exactly the ideal of a pert bump. Conceited? Smug?

These are thought crimes, but they are discovered through dress, accessories, and gesture: a bow, belt, hand, or parakeet on a discrete and defined bump.

Memoirist Maggie Nelson describes shopping at something very like a 21st-century Belly Piece Shop, putting on a “gelatin strap-on” in a Motherhood Maternity store to see what a jumper with a bow on the bump would look like. Yet a fake bump in a fitting room like this is intended for those who really are pregnant. Trying on prospective bridal wear is for prospective brides, and trying on maternity wear for mothers. Only in the crazy year of The Pad could everyone try on pregnancy for size. Imagine a flash-mob historical reenaction descending on Motherhood Maternity — dressed like the proto-punks of the 1790s in nipped-in military riding habits, big curly wigs, and feathered millinery — as they shoplift their gelatin strap-ons. Sacrilege.

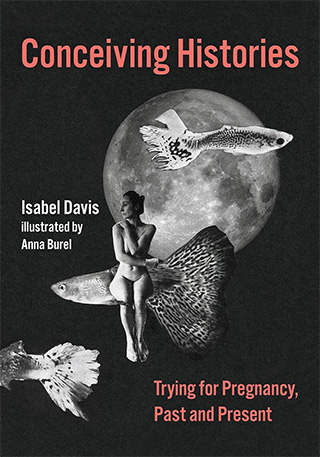

Isabel Davis leads a research theme on Collections and Culture at the Natural History Museum in London, and she is Honorary Research Fellow at Birkbeck, University of London, and Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Reading. Davis is the author of “Conceiving Histories,” from which this article is excerpted. “Conceiving Histories” is illustrated by Anna Burel, a London-based artist and illustrator whose artwork encompasses textiles, sculpture, drawing, photography, and collage.