The Uneasy Alliance Between Aluminum and Warfare

Aluminum has fascinated military strategists from its very earliest days. Most histories of the metal begin by noting that French emperor Napoleon III financed experiments by chemist Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville in the 1850s with the hope of developing light helmets and armor for his cavalry, but it remained so expensive that all he got was a breastplate for himself. However, with the establishment of the modern industry, production soared, prices plunged, and as early as 1892 the French military ordered several aluminum torpedo boats.

“United States cavalrymen fighting in the Spanish-American War,” notes a history of Alcoa Corporation, a major early producer of aluminum and the book’s publisher, “tethered their horses to aluminum picket pins, and infantry troops slept in tents pegged to aluminum stakes,” while Teddy Roosevelt himself carried an aluminum canteen as he “led his troops up San Juan Hill.”

However, these quaint details pale in comparison to the subsequent military adoption of aluminum, which the company itself described as “massive applications of aluminum to the terrible arena of modern warfare,” adding that it was its contributions to mobility and speed that made aluminum so crucial both to perpetuating war and to changing modern military strategy.

The aluminum industry helped to modernize warfare, and warfare helped to modernize the aluminum industry. As George David Smith writes in a different history of the company, “war was good to Alcoa,” with World War I enabling the company to increase production by 40 percent and to export ninety million pounds of Alcoa’s total primary output (152 million pounds between 1915 and 1918) to British, French, and Italian allies. Smith notes that “plant facilities were hastily expanded to meet demand, and shipments of bauxite from the company’s new mines in South America began in earnest.” In fact, during both World Wars I and II, about 90 percent of U.S. aluminum production went into military uses; the metal remains essential to many components of modern warfare.

It’s a central ingredient of BLU-82, known as the “daisy cutter,” used for carpet bombing Vietnam and more recently in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Described as the world’s largest non-nuclear weapon, it contains a slurry of ammonium nitrate, aluminum powder, and a polystyrene-based thickener, which when it explodes generates a massive pressure wave estimated at 1,000 pounds per square inch.

Our contemporary culture of innovation and entrepreneurship remains deeply entwined with the military-industrial complex.

In addition to bombs, a host of small arms make use of aluminum, including the M-72 light antitank weapon, the M16 assault rifle, and the barrel of the M79 grenade launcher. Missiles, meanwhile, make even more significant use of the light metal. The Hawk missile “depends largely on aluminum for its speed and maneuverability” according to Alcoa, and the Polaris missile requires 4000 pounds of the light metal, not to mention a few more thousand pounds of aluminum in powder form for its propellant mix. The Russian air-to-air R-27 missile, as well as India’s nuclear-capable Prithvi II, are also made of aluminum alloys.

Naval vessels, too, are heavily reliant on aluminum, which lends them speed, range, and maneuverability. The Navy’s destroyer-conversion program used 200,000 to 700,000 pounds of aluminum per ship in order to reduce the weight of deckhouses by up to 50 percent; whereas aircraft carriers use millions of pounds of it. On a smaller scale, “lightning speed and easy maneuverability are designed into 50-foot, all-aluminum ‘Swifty’ patrol craft,” says Alcoa — a ship many Americans know of today in relation to the “Swift Boat” ads that may have helped bring down John Kerry’s presidential run in 2004.

Perhaps a more surprising use of aluminum during WWII was as a radar countermeasure in the form of “chaff.” Britain’s Royal Air Force first used this secret new device, code-named “Window,” in its bombing of Hamburg in 1943. It consisted of bundles of over two thousand strips of coarse black paper with aluminum foil stuck on one side. Seven thousand bundles were dropped from a stream of 740 Lancaster and Halifax bombers and they were so highly successful in jamming Hamburg’s defensive radar, that the entire warning system was blinded: Hamburg was infamously reduced to ashes, and only twelve British bombers were lost.

It is fair to say that the entire history of innovation and technical development in the uses of aluminum was in many respects driven by the necessities of war, by aluminum’s terrible power for waging war, and by the intrigues, espionage, and industrial maneuvering for military research funding and contracts generated by war. This development led to what Eisenhower himself in 1961 warned was a dangerous “military-industrial complex” with “unwarranted power” built in partnership with aluminum producers.

Key investor in Alcoa, Andrew Mellon, “left his job as Alcoa’s Chief Executive to become the US Treasury Secretary in 1921, and kept this post for eleven years,” according to Smith, the author of Alcoa’s history, “while his company expanded into Europe and Canada, buying bauxite mines as well as factories and dam sites — as one of the world’s first real multinationals.” In other words, there were key ties between the international expansion and vertical integration of the industry, and the very heart of government. There were not only interlocking directorates across companies like Alcoa and Alcan, a Canadian aluminum manufacturer, but also linkages among the aluminum industry, the highest levels of government, and the government funding of warfare.

The international race to master aluminum technology was intimately linked, then, with the race for military dominance in flight, transport, weaponry, logistics, and eventually in aerospace and satellite communications systems. Today, light metal continues to play a critical role in defense. The U.S. Army Research Lab itself points out that “aluminum alloy armor has been utilized by the US government since the outbreak of World War II, and each year, the military procures about 5,000 vehicles, which translates to more than 30 million pounds of aluminum alloys that will be procured annually.” It also continues to be a crucial material for military-funded research and development, especially in regard to new nanocomposites, including at the cutting-edge nanomaterials engineering research facilities of my own employer, Drexel University in Philadelphia.

Our contemporary culture of innovation and entrepreneurship remains deeply entwined with the military-industrial complex, with serious implications for our ability to address ethical issues concerning global pollution, environmental destruction, and the huge effects of aluminum production on marginalized people.

So long as aluminum is crucial to the destructive capacities of warfare, no amount of greenwashing can hide its national military strategic significance and geopolitical importance.

The expansion of bauxite mining and alumina refineries has had devastating environmental impacts around the world, including especially dangerous recent spills of caustic “red mud” and water contamination affecting Indigenous and Quilombolas communities in Brazil; an environmental struggle in Jamaica to save its interior Cockpit Country from mining (about which I have co-produced, with Jamaican Director and Producer Esther Figueroa, a forthcoming documentary film called “Fly Me to the Moon“); major legal battles against Vedanta, which operates mines and factories in India and Zambia, for pollution and human rights abuses against tribal peoples; and a 2019 oil spill by a bauxite shipping tanker on Rennell Island, a remote Pacific coral atoll and World Heritage Site, where bauxite mining operations have “gouged red gashes and left gaping holes in the forest” while shadowed “by allegations of rampant corruption, deception of landowners and regulatory violations,” according to the New York Times.

This is all standard operating practice for an industry that has scoured the world for weak spots where environmentally lax mining could take hold and governments could be corrupted for corporate advantage. The ethical concerns are further magnified when corporations proclaim that they are operating in the interests of “sustainability” by creating materials for “green” solutions. As Olúfẹmi O. Táíwò recently argued in Pacific Standard, even Green New Deal supporters should beware of “climate colonialism” in which initiatives to slow global warming and build “green” economies lead to the domination of less powerful countries and taking of resources, land, and energy. So long as aluminum is crucial to the destructive capacities of warfare, no amount of greenwashing can hide its national military strategic significance and geopolitical importance.

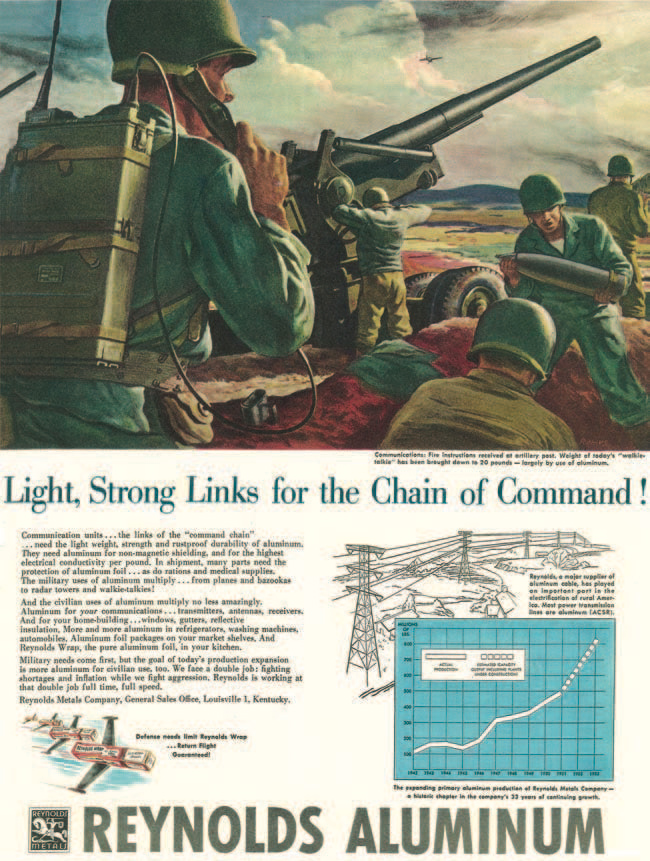

In 1950, the Reynolds Metals Company observed that our bombs over Germany were doubled in power through the use of aluminum powder. “Truly, the possibilities of the magic metal, aluminum,” they keenly observed, “are just beginning to be explored.” The future undoubtedly will reveal many more.

Mimi Sheller is a sociology professor at Drexel University and the author of “Aluminum Dreams,” from which this article is adapted.