The Tragic Downfall of ʿAṣfūriyyeh (The Lebanon Hospital for the Insane)

Aṣfūriyyeh (formally, the Lebanon Hospital for the Insane) was one of the first modern psychiatric hospitals in the Middle East. Founded by a Swiss Quaker missionary in 1896, ʿAṣfūriyyeh was an international hospital — indeed, a “cosmopolitan” one, to quote the British psychiatrist Maurice Aubrey Partridge, who likely visited the hospital in the 1940s. Patients came from all over the Middle East, including Latakia, Mosul, Alexandria, Haifa, and Tehran. Foreign troops from the British Commonwealth and Africa were also treated there, especially around the times of the two world wars, when the British and French troops occupied the premises of the hospital. Over time, however, this cosmopolitan population gradually withered, with the birth of new nations and the creation of new borders following the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire in the aftermath of the First World War.

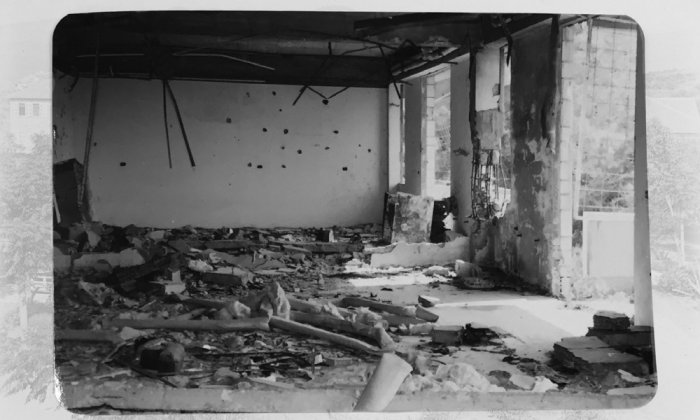

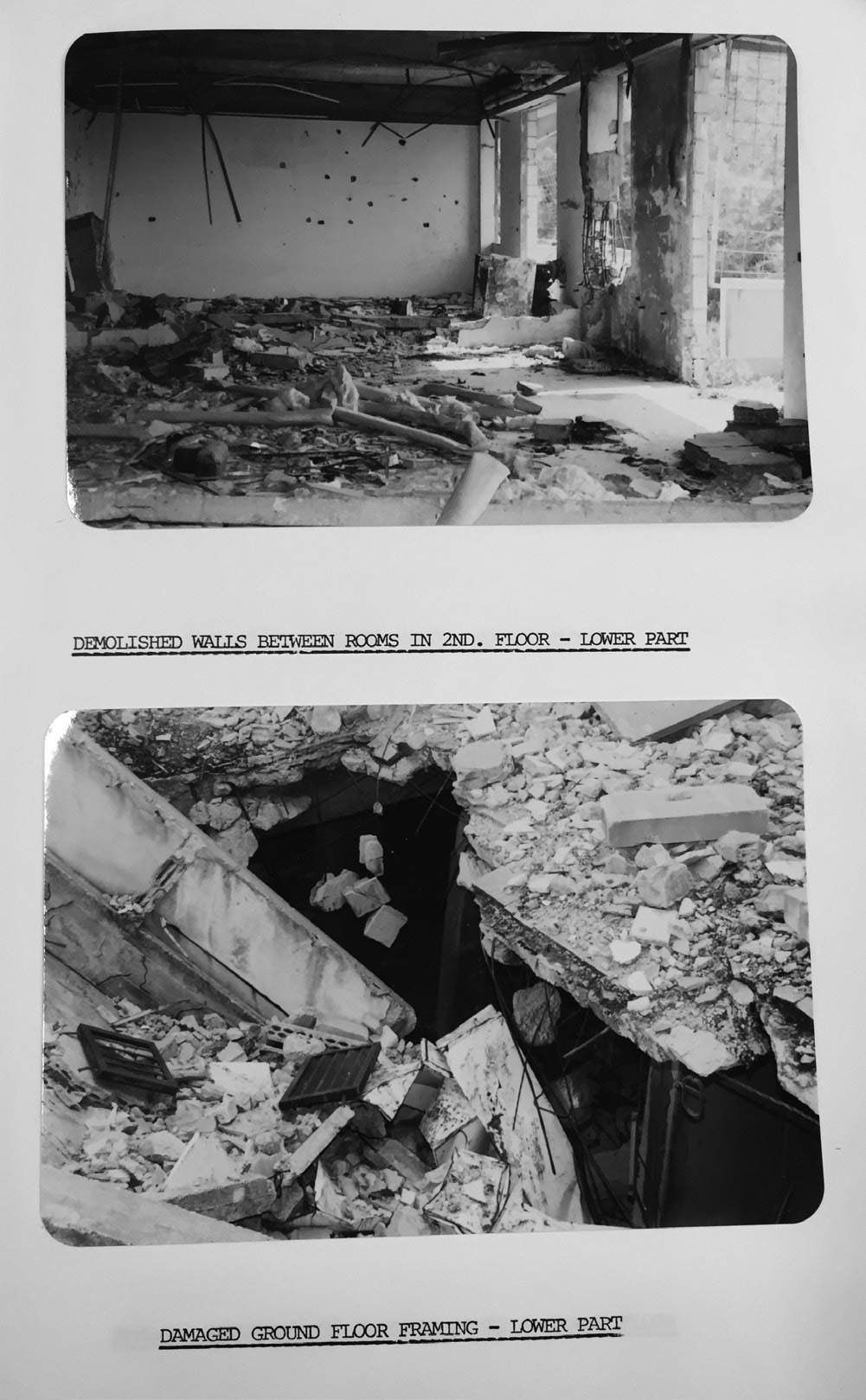

ʿAṣfūriyyeh (which in Arabic means “place of the birds”) closed its doors in 1982, a victim of Lebanon’s brutal 15-year civil war. Its history (including its tragic downfall) departs from the trajectory and fate of 19th-century psychiatric hospitals in the West. In contrast to the wave of deinstitutionalization and the antipsychiatry movement that swept across Europe, Great Britain, and the United States starting in the 1960s (which led to the dismantling of overcrowded and underfunded psychiatric institutions), in Lebanon it was a civil war that aborted a grand vision of social reform and the expansion of mental health care.

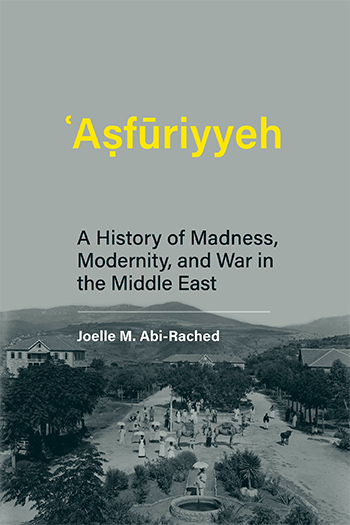

In the excerpt that follows, adapted from Joelle Abi-Rached’s book “ʿAṣfūriyyeh: A History of Madness, Modernity, and War in the Middle East,” Abi-Rached chronicles what it was like to live in, and especially manage, a psychiatric hospital during the sectarian civil war that erupted in Lebanon in 1975 and lasted through the Israeli invasion of the country in 1982, which coincides with the official closure of ʿAṣfūriyyeh. The text is also a testimony to those who lived and perished on the premises of ʿAṣfūriyyeh during the Lebanese civil war, whose stories we will never fully know — much like the stories of the several thousand people who disappeared during the war and are still missing. Indeed, writes the author in the introduction to the chapter from which this text is excerpted, their stories remain impressionistic because of the archival material, which consists chiefly of the reports and correspondence of Antranig Manugian, the hospital’s medical director during the war.

On 13 April 1975, shots were fired from a car that killed a number of people during the consecration ceremony for a new church in east Beirut, attended by Pierre Gemayel, leader and founder of the Kataeb (Phalange) party, a Christian political party that was created in 1936 inspired by the ethos of “discipline and order” that characterized Italian fascism and Nazi rule. A few hours later, the Kataeb militiamen retaliated by massacring all the Palestinian passengers of a bus returning to a refugee camp from a commando parade in Beirut. The events or “aḥdāth” (as the civil war is referred to in Arabic) that followed plunged Lebanon into darkness, chaos, and violence.

A few months later, a psychiatrist who had played a key role in enhancing psychiatric training in Lebanon was kidnapped and taken to a Palestinian camp, which had become a zone of regular conflict between the Phalangists and the Palestinian fedayeen. As was the case with many other random sectarian-based abductions and assassinations, the psychiatrist was kidnapped because he was Christian. Although he was released unharmed, the violence toward patients and the medical personnel intensified in the days, indeed weeks and months, that followed. At ʿAṣfūriyyeh, where the kidnapped psychiatrist worked, Muslim staff and students — especially the Palestinians among them — now feared reprisals and executions. (It is worth noting that the hospital was in a predominantly Christian area controlled by Christian militias in a sectarian war in which being a Christian or a Muslim on the wrong side of the conflict could be fatal.) They did not have to wait long for on November 5, 1975, armed men forced their way through the hospital barrier and kidnapped several Muslim students. Manugian reported in his notes: This was a “severe blow to the dignity and neutrality” of a charitable hospital like ʿAṣfūriyyeh. Indeed, the hospital, which was founded at the Ottoman fin-de-siècle to serve “the poorest of the poor,” had managed to remain unscathed despite the tumultuous sociopolitical upheavals in the region, including two world wars, the redrawing of national borders, and the relentless Israeli-Arab conflicts.

The doors of hell had opened, the birds flew, and the once-upon-a-time pastoral “place of the birds” had become the place of ruins and desolation.

The militiamen, it turned out, were avenging some of their partisans who had been kidnapped the day before by Muslim factions in West Beirut. As the journalist Charles Glass aptly wrote, “when the country itself went insane, the doors of the Asfourieh [sic.] were opened and the birds flew.… forty years later … Asfourieh … was an empty shell in the no-man’s-land between the two halves of the divided city.” This is exactly what had happened: ʿAṣfūriyyeh had become the battleground of sectarian politics and ruin-nation. The doors of hell had opened, the birds flew, and the once-upon-a-time pastoral “place of the birds” had become the place of ruins and desolation.

The students were released the following day with one Palestinian student suffering serious physical injuries that were to become an all-too-normal manifestation of the brutality that was regularly inflicted on innocent civilians. This is how violence gets normalized during war. But it is also worth remembering that such brutality and violence are quickly forgotten once wars end as if all-too-natural in an all-too-pathological setting.

The kidnappings included staff and students as well as prisoners from the hospital’s “forensic unit.” Many of the inmates in that specialized unit, which was inaugurated in the early 1960s, were being treated for substance “abuse” (to use the terminology of the day), while others had committed more serious felonies. It is important to note though that ʿAṣfūriyyeh was among the first institutions in the Middle East to have medicalized “criminal insanity” and later other substance use-related disorders. Before these institutional innovations, individuals accused of consuming or selling what were deemed “toxic” substances were thrown in prison, forgotten and unattended for.

On January 21, 1976, following a relatively quiet day, several armed men disarmed the gendarmes who were guarding the forensic unit and took away many inmates, leaving the inmates who were of the opposite religion in a state of panic. But this time, the prisoners had been kidnapped by their own relatives. Ironically, the (now former) prisoners called Manugian to express their gratitude for the care they had received at the hospital and apologized for “letting him down for reasons beyond their control.”

On the morning of March 14, 1976, armed men — among them former patients of the forensic unit — took away several inmates after disarming the gendarmes. (Did they come to release friends and relatives or to exact revenge? The archives are silent.) A few days later, several armed men again attacked the forensic unit, this time freeing thirty prisoners. Later that day, still another group of armed men came and asked for the release of three specific prisoners, whom they named. The gendarmes, who, by now, were both helpless and hopeless, handed the prisoners over without any resistance. Several of the prisoners who were taken away that day were suffering from serious mental disorders, the psychiatrist noted. Although the local authorities were informed of the various infractions, they were utterly powerless. The country had plunged into total lawlessness and darkness.

The same group of armed men visited the next day, saying that they wished to release other inmates. Again, the gendarmes presented no opposition while the medical director’s efforts to try to reason with them fell on deaf ears. Their intention was clear: they were releasing Christian men who were being treated for drug addiction as a favor to their families. At the same time, they were kidnapping and killing Muslim patients in retaliation for similar violence that had been perpetrated against their own partisans in Muslim-controlled areas. On March 18, 1976, three of the prisoners who had been released by the armed men were found dead, likely executed in cold blood.

The bombings, heavy shelling, and machine-gun fire continued the following days. The psychiatrist felt the need to note in his meticulous observations that he had to increase the prescription of tranquilizers to calm both patients and staff. On March 20, one of the prisoners who had been taken away by the armed men came back to the hospital. He insisted to be readmitted. The world outside ʿAṣfūriyyeh seemed to him manifestly more insane and unfathomable. Baffled by this turn of events and unwilling to take any unnecessary risks, the gendarmes refused to take him in.

The continuous shelling caused heavy damage to the hospital, and the physical violence against the patients continued unabated, with more patients being killed, injured, or kidnapped. The militiamen had also started to assault female patients. By March 29, 1976, every one of the hospital’s buildings had been hit at least once. The gendarmes now utterly desperate handed the keys of the forensic unit to Manugian and walked away.

The peaceful coexistence across sects that was eroding on the national level managed to remain intact at ʿAṣfūriyyeh throughout the war, though it was increasingly being tested. Anonymous callers made repeated phone calls in which they threatened various staff members. Manugian regularly met with the staff and the students to appease their anxieties and fears. He also praised their ethic of care, which placed the welfare of the patients “above all personal, religious and political considerations.” Astonishingly, the psychiatrists at ʿAṣfūriyyeh continued to offer counseling at the dispensaries and outpatient clinics that were located in Beirut and outside the capital. These services were provided free of charge to an increasingly nervous, anxious, and traumatized population.

Schizophrenia, paranoia, anxiety, depression, and other emotional distress caused by the civil war have overwhelmed families, shattered individuals, and continue to linger on decades later.

Indeed, many continued to suffer from these newly acquired traumas long after the war officially ended in 1990. Some succumbed to their fears, phobias and anxieties. Others died by suicide. Still the specter of war continued to haunt many families. Tragic stories abound; of a relative who “lost his mind” after witnessing some horrific act of violence, of the unbearable grief of losing a child killed by shrapnel, a car bomb or a mine, of a relative who disappeared after returning from work and was never accounted for, of a career aborted because of the war, and so on and so forth. As one journalist put it, “the voice of the missing still resonates in Lebanon decades on.” Schizophrenia, paranoia, anxiety, depression, and other emotional distress caused by the civil war have overwhelmed families, shattered individuals, and continue to linger on decades later.

Despite the sacrifices and courage displayed by the staff and administrators at the hospital, rumors were now circulating that patients were systematically being killed. According to one newspaper, the hospital had failed to protect its patients from sectarian abductions and assassinations. (It is true that the medical director and the staff mostly felt helpless; the belligerents rarely, if ever, took their opinion into consideration. It is also true that despite the abductions of several patients, some had returned unharmed, and some had been safely returned to their families. But who are we to believe in times of war?)

A ceasefire in April 1976 allowed the discharge of the few remaining patients since it was becoming too dangerous to remain on the hospital premises. Their transport was a delicate affair. The Muslims among them had to be safely transferred to Muslim-controlled areas and the Christians to Christian-controlled areas. In addition, patients who identified as “Druze, Jewish, Buddhist, and atheist” were also transferred. This moment marks the beginning of the disintegration of a community that had, ironically enough, managed to provide a model of harmony and peace in which “diverse races, creeds, temperaments and social conditions” had coexisted for decades.

Joelle M. Abi-Rached is Lecturer on the History of Science at Harvard University. She was trained as a medical doctor, a philosopher, and a historian of medicine. Her work focuses on the social, political, ethical and economic aspects of medical and psychiatric practices, public health, and global health. Her recent book, “ʿAṣfūriyyeh: A History of Madness, Modernity, and War in the Middle East,” from which this article is adapted, received the Jack D. Pressman-Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Development Award in 20th Century History of Medicine or Biomedical Sciences awarded by the American Association for the History of Medicine.