‘The Silver Bridge’: Gray Barker’s Psychic Travelogue

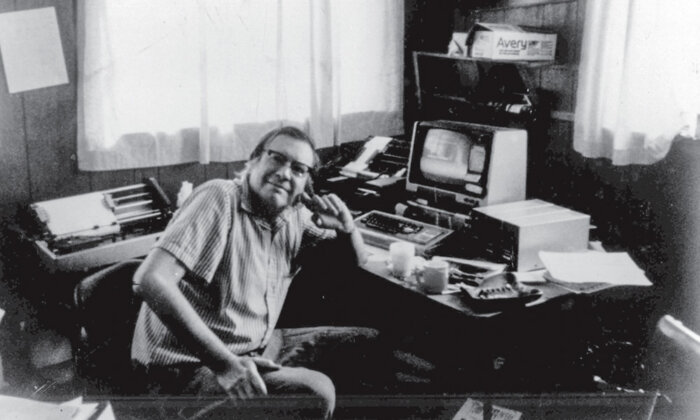

UFO research is a fringe field, and Gray Barker was a fringe figure within it. But in that world of mysterious sightings and strange occurrences, the fringe has a stubborn habit of migrating to the center. An author and unreliable narrator of implausible stories, Barker established his reputation with one of the first flying saucer fanzines, The Saucerian, which he launched in 1953 and developed into a hub for some of ufology’s most enduring mysteries, including the Men in Black, the Philadelphia Experiment, and the Mothman. The science fiction author Jack Womack once described him as “a complex figure with wild talents for both hoaxing and propagandizing.”

By the close of the 1950s, Barker had established a book publishing imprint that brought out some of the strangest UFO-related books of the era, with a particular emphasis on flying saucer contactees. Saucerian Books became a platform for those whose stories were too unusual, far-fetched, or crudely written for more mainstream publishers.

Barker’s success as a publisher rested on his reputation as an author. Among his books were the conspiratorial and sensationalistic “They Knew Too Much about Flying Saucers,” which introduced the Men in Black to the world at large, and the more experimental “The Silver Bridge.”

Though “They Knew Too Much” is arguably Barker’s most influential book, “The Silver Bridge” is his most self-consciously literary work. In a certain sense, it is the first book-length exploration of the Mothman sightings that took place in Point Pleasant, West Virginia, in 1966 and 1967. But like its much better-known companion, journalist and ufologist John Keel’s “The Mothman Prophecies,” it is also something much stranger and much more expansive.

To say that either book is about the large bird that newspapers named the Mothman is a vast understatement. Barker’s book is not a typical report on Fortean subjects but something more akin to a novel. But perhaps the most rewarding way to approach “The Silver Bridge” is as a psychic travelogue. Barker did not travel far geographically in researching the strange events in the Ohio River Valley in 1966 and 1967, but the book explores a vast terrain in the outlands of the human experience.

Barker began work on the book in 1968, telling John Sherwood, a young writer whose own UFO book he had recently published, “I’m now in the state of labor, in bringing forth a monsterous [sic] child, a book which I’m going to call ‘MOTHMAN: THE GREAT BIRD THAT TERRIFIED POINT PLEASANT.’” But it soon became apparent that the book was something else. Early in the writing process Barker told Sherwood that he was “throwing in a little fantasy,” and that he expected the result to “transcend the usual crap such as GRAY BOOKERS BARK of this and that.” By the fall he no longer considered it to be about the phenomena so much as “the people who see monsters and saucers, etc.” He later told John Keel:

I started writing this as a more or less straight account . . . but the other stuff got to creeping in. I figured that a straight saucer-monster book wouldn’t get too much mileage in the trade anyhow, so I just went ahead and did it the way I really wanted to do it. To me, it captures the feelings and emotions I experienced while in Point Pleasant doing the investigations, which somehow, turned out to be a hauntingly beautiful thing.

“The Silver Bridge” opens, straightforwardly enough, with an account of Barker’s trip to interview Newell Partridge, a resident of New Martinsville, West Virginia, whose dog disappeared under mysterious circumstances in November 1966. Ultimately, it is not the details of the interview on which Barker lingers, but on the impact of the events on Partridge’s six-year-old son, who begins each day by going outside and calling for the missing dog.

In the second chapter, however, Barker makes clear how different his intentions are from those of the usual paranormal book. The chapter describes a being identified only as “The Recorder” who arrives in the Ohio River Valley with sophisticated audiovisual equipment. The Recorder harkens back to the isolated vigil of Barker’s early poem “Mountain Poet,” using his solitary vantage point to observe the human tapestry below. With his equipment in place, the Recorder collects information on the Mothman, the Men in Black, and flying saucers, before turning his attention to another activity on the hilltop — performing a rendition of “The Symphony of the Horns.”

As the initial moments of the chapter borrowed from “Mountain Poet,” this bizarre scene draws from Barker’s unpublished poetical work “Seven Sagas” and its “Symphony of the Horns” — a Dadaist collection of sound effects that attempts to translate a bizarre, imagined musical piece into language. Once the symphony is playing, the Recorder performs a final series of tasks:

He turned on all of his equipment. From his Television Kit he withdrew great Idiot Cards, and hung them on over-size easels. Throwing away all pens and selecting a huge black marker from his chest, he filled the Cards with large characters, telling the story that was occurring below.

Now he could see all things in the valley. He could penetrate the walls, see through the curtains, and behind the masks. Suddenly he knew what was happening. He knew the secrets of everything and everybody.

And he knew all the things the people of the valley were thinking, and they were good. At last he knew that they loved him, and that he loved them, and that he loved all mankind.

And so it was that the greatest power of his experience came upon the Recorder, and he became capable of Recording all things.

And he became capable of the gift of Reorientation, so he took liberties with time and space, and he reassigned names, and he lifted people from one place and put them down into another, and the people below loved him more, and they applauded, and they gathered in a great moving human throng, advancing upon the Recorder.

They carried him off the mountain, into the valley, across the great bridge into Ohio, shouting.

The Recorder chapter provides context for the remainder of the book: It is not science, but art, in which a godlike, sometimes invisible witness has altered the events described to create a more beautiful symphony. And rather than seeing this as a betrayal of his scientific Recording, the people of the world love him all the more for it.

The Recorder is at once an authorial stand-in and a commentary on the entire field of ufology.

The Recorder is at once an authorial stand-in and a commentary on the entire field of ufology. Barker said as much in a letter to writer and UFO skeptic Robert Sheaffer in 1980: “I tried to clue my own role as that of The Recorder, who also, I thought, could be a composite of UFO ‘researchers’ in general.”

Convinced of his unique importance and insight, the Recorder believes he is the only one capable of accurately describing the events he witnesses. But he willfully distorts the events to fit the metanarrative he is crafting. In one sense this is a confession, since “The Silver Bridge” contains fictional material, but it is also a comment on UFO authors in general, who are more than willing to leave out details that would tend to overcomplicate a story or contradict a chosen metanarrative.

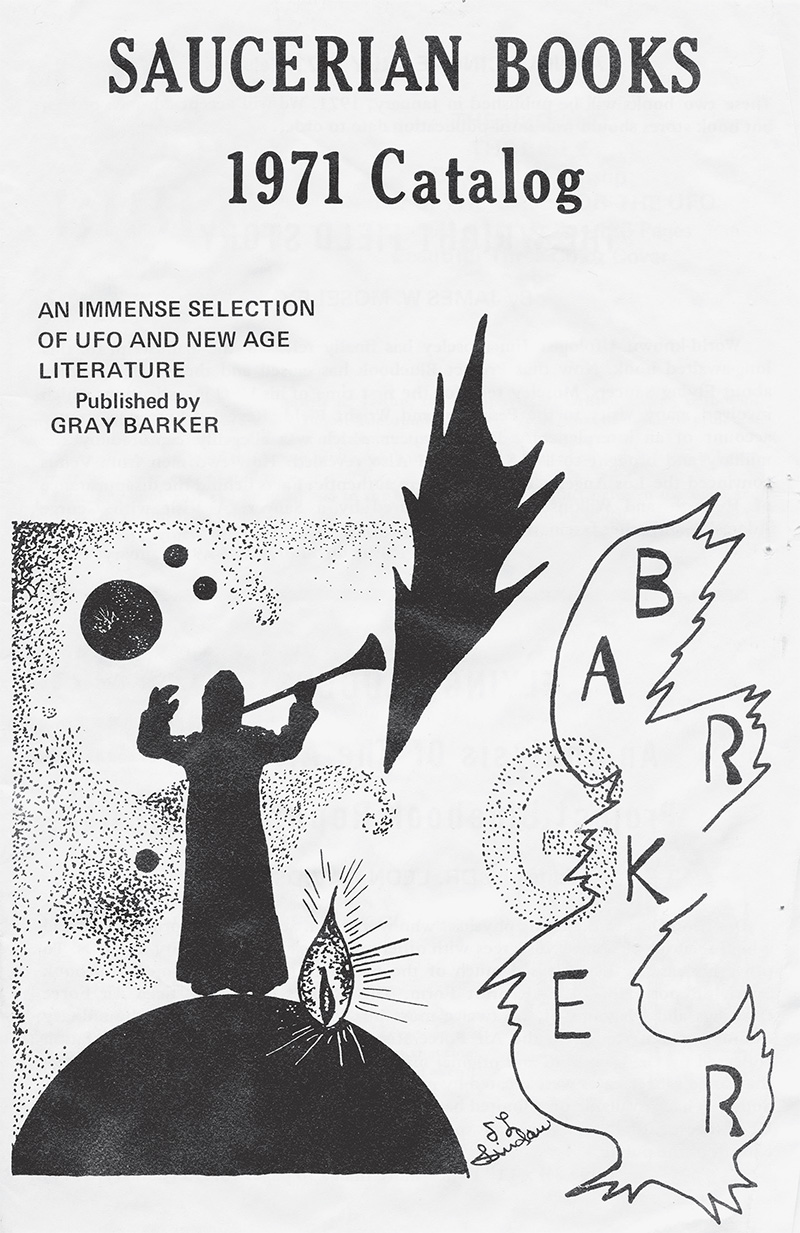

Though Barker periodically appears as a first-person narrator in the book, most of it is written in third-person omniscient narration. This chapter suggests that the Recorder — whose vision can “penetrate the walls” — is the omniscient narrator. Gene Duplantier’s jacket illustration depicts a jagged, twisted suspension bridge in the foreground, but in the background, in the upper right corner of the jacket, is a small, robed figure on a hilltop, playing a horn. This is the Recorder, conducting his strange symphony over Point Pleasant. Following the book’s publication, this image of the horn-playing Recorder appeared on numerous Saucerian catalogs and publications as a sort of logo or emblem, suggesting that Barker saw his role as publisher as an extension of the Recorder’s artistic distortion as depicted in “The Silver Bridge.”

Barker’s exploration of other events from the Ohio Valley similarly foregrounds his artistic interpretations of events. A chapter concerning Men in Black sightings culminates in an invented narrative from the point of view of Agar, one of the inscrutable MIB, as he attempts without success to intimidate a young boy who has taken a picture of a UFO. Barker depicts Agar as a weird, emergent being, somehow created by humankind.

But despite Agar’s inhumanity and his threatening nature, the boy befriends him, ultimately telling him, “I know that you are dying, and I don’t want you to go!” The boy, perhaps a young UFO enthusiast or a stand-in for Keel, clings to that which tries to frighten him, just as the realm of ufology — a field that Barker frequently equates with childhood — had embraced Barker’s and Keel’s stories of enigmatic MIBs.

A similar chapter introduces Indrid Cold, a spaceman from the planet Lanulos who travels in a strangely dilapidated craft. Cold, like Agar, seems unaware of his origins or mission and receives his knowledge from a distant authority known only as “the Interpreter.” Barker privately identified this figure as Woodrow Derenberger, a West Virginia salesman whose widely publicized 1966 encounter with Cold drew Barker to Point Pleasant for one of his rare on-the-ground investigations. Cold, tethered by silver cables to his ship and to the Interpreter, is a puppet — his reality shaped by Derenberger’s storytelling. Where Keel would tie Cold’s puppet strings to an unseen, unknowable ultraterrestrial source, Barker grounded them on Earth, in the hands of Derenberger himself.

This is God as a hoaxer, or the hoaxer as God, dangling bait with which to capture earthbound explorers of the unknown — and a fitting description of Barker himself.

Barker returned to this image in one of his final books, describing a “remarkable Vision” that summed up his view of the universe, God, the flying saucer mystery, and the meaning of his own life: “In this vision an incomprehensible Being of enormous size and power — perhaps larger than our Globe itself — dangled huge cables from the sky. Like some gargantuan giant wielding enormous fishpoles, this Force cast bait consisting of disc-shaped objects not unlike modern UFOs.” In “The Silver Bridge” Barker left some mystery as to what was on the other ends of the cables controlling Cold and his ship. Here he shows us who is pulling the strings. This is God as a hoaxer, or the hoaxer as God, dangling bait with which to capture earthbound explorers of the unknown — and a fitting description of Barker himself.

The narratives of Agar, Cold, and the Recorder all orbit around the purportedly central subject of “The Silver Bridge”: the Mothman itself. Barker spends two chapters recounting the stories of witnesses Linda and Roger Scarberry and Steve and Mary Mallette, but much of the Mothman content in the book is entirely fictional. Barker was particularly proud of chapter 7, “The Winter Wind,” which tells the invented story of Jimmy Jamison, a borderline juvenile delinquent living with foster parents whose sighting of the bird creature is related to his compulsion to “wander the back streets.” The narrative strongly hints that, on one of his nocturnal jaunts, Jamison had had sex with an alcoholic drifter — possibly a stand-in for Barker — in exchange for a single dollar bill, which then becomes a sort of totem for him: “the only evidence that, for him, had separated this real experience from fantasy.”

When Jamison sees the Mothman through his bedroom window, he associates the bird creature with his absent father, known to him only from a photograph, prompting him to call out: “Mothman! Please come back, Mothman! . . . I love you, Mothman!” Sending this chapter to Sherwood in advance of publication, Barker noted its fictional status, adding, “The tale is, of course, not about mothman, but the sympathetic treatment of a disturbed child.” Another Mothman witness is repurposed from Barker’s memories: the dog Old Ponto, Barker’s own childhood pet, in the chapter “The Dog Who Saw Mothman.”

A chapter late in the book depicts the collapse of the eponymous Silver Bridge, framed with a Mothman story that Barker privately admitted was “constructed out of whole cloth.” This chapter presents the story of a fictional man named Frank Wentworth, whose wife, Ida, has left him, and is staying with her sister across the Ohio River. Distraught, Frank visits a bar on December 16, 1967, and while there imagines Ida transforming into a bird: “He had often looked at her and mentally transfigured her into an old hen, pecking at him in great frenzy.” From this reverie he begins to imagine that Ida is traveling back to him, and at this moment the bridge collapses with a horrendous roar. Frank rushes home to find his house in disarray and a strange shape occupying his bed:

Red flashing eyes burned into his. Then with seeming confusion, and a flapping and gurgling sound, the thing tumbled sidewise to the floor, flapped again, upset a lamp, and then righted itself unsteadily. He retreated to the living room, tripped on the edge of the rug, and fell. As he was getting up, hoping to run and escape from the incomprehensible horror in the bedroom, it waddled through the door. He noted another facial feature besides the eyes: It had a long sharp beak which slanted downward, almost corresponding to a nose. . . . The great bird — that was as close as he could describe it to himself — again righted itself, leaped toward the large picture window, and with a crashing and splintering of glass, disappeared.

The creature Barker describes in this chapter is clearly a mud-drenched sandhill crane, made strange mainly by its dirtiness and its unexpected appearance inside Frank’s bedroom. But in the context of Frank’s perception and this narrative of it, it is surely something else as well — either Ida transformed or a harbinger of her death in the bridge disaster.

Ultimately, however, it doesn’t matter; the description of Frank’s confused experience is all we have access to and all that the book hopes to communicate. Whether bird, angel, demon, or something stranger, the Mothman grows from witnesses’ ideas about it — and from readers’.

Gabriel Mckee is Librarian for Collections and Services at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University. He is the author of several books, including “The Gospel According to Science Fiction,” “Pink Beams of Light from the God in the Gutter,” “Evermore: The Persistence of Poe,” and “The Saucerian: UFOs, Men in Black, and the Unbelievable Life of Gray Barker,” from which this article is adapted.