The Secret Life of Videocassettes in Iran

In 1983, just as a burgeoning video rental industry found its footing in Iran, the Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance issued a ban on the personal use of all video technology. The ban would last for over a decade and would set the stage for the incredible tale of how everyday Iranians nurtured an underground world of videocassettes.

“Selecting and watching movies from the video dealer’s collection was often a family affair, as videocassettes transformed the television set from simply a source of news and information to a movie screen capable of nearly anything,” writes Blake Atwood in the introduction to his book “Underground: The Secret Life of Videocassettes in Iran.” At turns illuminating, uproariously funny, and unexpectedly tender, “Underground” offers a deeply researched account of a fraught and elusive chapter in Iran’s contemporary history.

Atwood, a professor of media studies at the American University in Beirut, draws on archival sources including trade publications, newspapers, memoirs, films, and laws, but at the heart of his book lies a corpus of oral history interviews conducted with dozens of participants in the videocassette underground. As such, the book is as much a reflection on how people remember, interpret, and reinterpret past experiences as what the underworld actually was.

Something like a video ban may seem insignificant given the violent oppression we are seeing today, but the underground Atwood describes reveals a great deal about how people construct vibrant cultures beneath repressive institutions. It was not just that Iranians gained access to banned movies, he writes, but rather that they established routes, acquired technical knowledge, broke the law, and created rituals by passing and trading plastic videocassettes. We asked Atwood about the role of video dealers as cultural intermediators, what life was like in Iran during this uncertain period, and what became of the underground network after the ban was lifted.

The Islamic Republic of Iran was established in 1979, followed by one of the darkest decades in the country’s contemporary history. It was during this decade that the government banned the personal use of home video technology. Can you describe what life was like in Iran during this period? What was the punishment if you got caught distributing videocassettes?

A lot of scholars of Iran focus on the Revolution of 1978-1979 as the most important event of the 20th century. In “Underground,” I challenge that idea — not by discounting the significance of the Revolution but rather by decentering it a bit and looking to the 1980s as a period when the Islamic Republic consolidated a lot of its power. It’s an attempt to think about continuities and ongoing processes rather than simply breaks and ruptures. The Iran-Iraq War, which lasted between 1980 and 1988, is crucial to understanding the 1980s in Iran. It was the perfect excuse for the newly established Islamic Republic to form and implement a very terrifying vision of governance. Although the Iran-Iraq War began with an Iraqi invasion, it is well-documented that the Iranian government refused ceasefires and continued the war because it advanced its own domestic goals. The Islamic Republic took advantage of people’s shock and awe during the war and their heightened patriotism to pass really rigid and extreme laws and policies.

One such policy was the outright ban in 1983 of video technology, including videocassettes, video players, and camcorders. Of course, throughout the 1980s, governments around the world were figuring out how to deal with the new medium of analog video, which offered great power to ordinary people to copy and distribute audiovisual material. While most governments tried to regulate how people used video or what kinds of content could be produced on video, few governments took the extreme step of banning the technology altogether. In Iran, the video ban — which lasted for over a decade until 1994 — was consistent with other cultural policies at the time, which attempted to control the sights and sounds that people had access to.

What is really fascinating about the video ban in Iran is how spectacularly it fails. During the decade-long ban, the circulation of movies on video doesn’t only continue; it grows by leaps and bounds. An entire underworld of videocassettes emerges. An underground rental industry forms, with individual video dealers copying and distributing movies on video. These cassettes — although technically banned — are reaching almost every corner of the country. The reason that this underground world of video develops is that people wanted to watch movies, and what was available on video was completely different from the content on cinema and broadcast media, which were saturated with official state messaging.

Dealing in videocassettes — and sometimes even watching them — could lead to harsh punishments, including prison time, fines, and lashings.

Although lively and robust, this underworld was not without risk. Dealing in videocassettes — and sometimes even watching them — could lead to harsh punishments, including prison time, fines, and lashings. What’s important here is that people maneuvered around this harsh policy, and I think that teaches us something about how power operates under the Islamic Republic. Ordinary people did not necessarily push back against the video ban policy as such, but they did refuse to acknowledge it in their everyday lives and practices. Because of that, eventually even the government had to admit that it had made a mistake in trying to ban this medium.

How did you become interested in the underground world of video, particularly in the Middle East? And can you talk a bit about how you researched “Underground”?

This is the most common question I get when I speak about this research project. Any book has multiple genesis stories, and in this case, I stumbled into the underground world of videocassettes in Iran for both personal reasons and intellectual reasons. One of the driving forces behind this book is my own relationship with videocassettes. I grew up with movies on video, and I wanted to understand that experience better. What kinds of emotions did people develop with videocassettes? And how did the affordances of that technology and attempts to regulate it shape individual experiences of it? For me, Iran was a very natural place to think through these questions, and it represents a bigger project of mine to challenge the fact that so many of our accounts of media technologies assume North America and Europe as normative sites for theorization. Indeed, I wrote a book a few years before “Underground” about the film industry in Iran in the 1990s and 2000s, and one aspect I was exploring in that book was the arrival of digital video technology to the industry and how it changed what it meant to make a film in the country. When I went to contextualize that moment of digital video historically, I realized that very little had been written about the story of analog video technology in the country. So that was a big motivation to make the longer history of video in Iran known to a broader readership.

Researching “Underground” brought me to some pretty unexpected places. Because videocassettes were banned for so long, we have very few sources that might illuminate how ordinary people experienced the technology. This is doubly true since it is especially hard to find sources related to domestic consumer technologies, since private lives are rarely attested to in public records. In order to overcome this hurdle, I conducted dozens of oral history interviews with various people who participated in the production, distribution, and consumption of movies on video in Iran in the 1980s and 1990s. As a result, the book is very invested in storytelling and reflecting as much on how people remember videocassettes as what this underworld actually was.

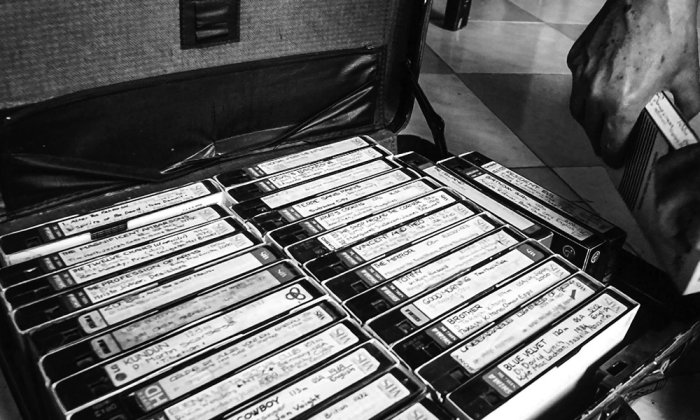

I think that’s part of what makes it so interesting — it’s surprisingly intimate and personal for what is ostensibly an academic monograph. That reminds me of one of my favorite chapters, on video dealers. You describe Hamid, who, thanks to his friendly face, “passed through the streets of Tehran unnoticed with a large briefcase full of Betamax cassettes in tow” delivering up to 10 videos a week to waiting clients. What did the work of video distribution represent to dealers like Hamid?

When I first started studying the underground world of videocassettes, I read every source that was available from Iran during that period, including newspaper articles, trade publications, and laws and policies. I noticed that the public discourse on video dealers really took shape around the motif of a money-hungry criminal who was dealing in movies on video — often alongside other illegal products like alcohol — just to make a buck.

However, when I spoke to video dealers, the people who were actually involved in producing and distributing underground videocassettes, I discovered a very different set of motivations. Although video dealers potentially made good money, they almost never described their work in that way. Instead, they spoke of a desire to be close to the movies, of an opportunity for social mobility, and of a chance to provide people with entertainment and escape during a very difficult period in the country. In short, this was self-actualizing work that meant a lot to the people who performed it. This feeling was often reciprocated, as ordinary consumers expressed their fondness and respect for their video dealers, who opened up a world of entertainment that otherwise wouldn’t have been available to them.

Dealers spoke of a desire to be close to the movies, of an opportunity for social mobility, and of a chance to provide people with entertainment and escape during a very difficult period in the country.

Ultimately, video dealers in Iran in the 1980s and 1990s teach us a lot about the labor of informal media distribution, even today. Just as the Iranian government viewed video dealers simply as criminals, today’s intellectual property rights regimes also villainize informal distributors like pirates. But this kind of work is much more complicated than just crime and money. People’s identities are attached to their livelihood, and informal distributors do important work supplying access to media, especially to those who have been left out of the global economy.

In that same chapter, you explain the creativity implicit in the work that dealers performed — the care they put into labels, summaries, critiques, and suggestions, which played a part not only in how the movies circulated in Iran but also in how people made sense of them. I’m thinking of the section about Omid in particular, who recalled that “each time the video dealer opened his briefcase, a minute of silence would ensue as the entire family read the titles and genres of each of the videocassettes.” Can you elaborate on the creative role of the dealer?

One thing I really wanted to emphasize in my chapter about video dealers is the important role they played as cultural intermediaries. They were cultural workers. Although it would be easy to view them simply in terms of logistics — of transporting commodities from point A to point B — they actually did a lot of other important work to help movies make sense to Iranian viewers at the time. The underground world of videocassettes in Iran wasn’t just about a new media technology or the ban policy; it was also about the preservation of movie culture in the country.

Video dealers were at the heart of that project. They were gatekeepers and tastemakers. They decided what movies would ultimately be available for rent, and they put a great deal of effort into curating their selection in such a way that would resonate with their customers. Globally, the rise of videocassette technology opened up the possibility of choice that did not exist when people were confined to movie theaters and TV schedules. Videocassettes represented the ability to choose what you watched, but that was a process (and a technology) that needed to be mediated by some sort of expertise. Video dealers provided both the technical and creative knowledge to guide consumers through these choices. It would be easy to brush aside something like labels, but the story of Omid that you mentioned highlights how these details figured prominently into the experience of accessing, watching, and understanding cinema during this period.

What kinds of films were people most interested in watching?

This is a very interesting question. In short, people were interested in watching whatever they could get their hands on. My interlocutors almost always regaled me with a story of watching a movie even though it was such a bad copy they could barely follow what was happening. You have to remember that video dealers were trying to make the most of the limited stock of videocassettes they owned, so they would copy over old movies to make room for new ones. This was a rental system, so it was important to keep the selection of movies up to date. Often copies of movies were derived from copies of copies of the original, and the videocassette preserved all of the glitches and wear-and-tear of its predecessors.

That being said, what was available in the video rental economy in the 1980s and 1990s was a vast selection of global cinema. When I tell friends and colleagues about this research, a lot of them assume that it was mostly Iranian films being circulated on video. However, nothing could be further from the truth. It’s true that Iranian movies — especially those from before the revolution — made their way into the circuits of underground distribution. However, they were just one tiny part of a very eclectic, very global mix of cinema being consumed in Iran at this time. Hollywood films were very popular, and so were Indian films. My interlocutors also remembered watching movies from Europe and East Asia. Disney movies really stood out, especially for those who were kids at the time.

Hollywood films were very popular, and so were Indian films. Disney movies really stood out, especially for those who were kids at the time.

In some ways, foreign films entered more easily into the underground video network because they were already distributed on video elsewhere. The original (or a copy of the original) just needed to be smuggled into the country through the airport or over a land border, and it could be copied an infinite number of times. However, Iranian films needed to be converted to video, an expensive and time-intensive process that was difficult to perform given the ban.

What happened to the underground network when the ban was lifted in 1994?

To the surprise of the Iranian government, not much changed when the video ban was lifted in 1994. After running efficiently and effectively for over a decade, the underground network — which was a complex and intricate system for video distribution — could not be disrupted by a slight shift in policy. Indeed, although the lifting of the ban meant that videocassettes as a technology were no longer illegal, this did not mean that everything was suddenly available. As the government lifts the ban, it also creates a monopoly over the formal distribution of movies on video, which had to undergo the same rounds of censorship and regulation that other media content followed. As a result, official lists of titles available for rent after 1994 are extremely limited. Those that do exist are often severely censored. Therefore, ordinary people continue seeking out and using the underground network to fulfill their desires for movies on video.

One interesting pattern I noticed during my interviews was the denial that a ban ever existed. Many of my interlocutors — ordinary consumers of movies on video in the 1980s — insisted that videos had never been outright banned. Of course, I knew this wasn’t correct; I had read all of the official accounts of the ban. But this was a very telling moment in my research, as I realized that the ban was somewhat incidental for many people. In other words, it was important to the development of this underworld of videocassettes but, once in place, people didn’t really notice the fact that the ban was lifted because they still depended on their underground video dealer to supply them with the kinds of movies they were excited to watch.

In the final chapter, you explore how people have sought to remember, record, and represent the unique history of analog video technology in Iran. What’s the significance of these public memories?

I started writing this book at a time when there was a global nostalgia for the 1980s, including in Iran. In the mid-to-late 2010s, there were a number of films, popular essays, and social media accounts that nostalgically looked back to videocassettes and their unique history in Iran. A lot of these efforts were highlighting the absurdity of the underground world of videocassettes. It sure makes for a good story — and people certainly laugh about it now — but it was also bizarre and unfair. The public memories around video bring into focus what it meant to be indoctrinated as a citizen under the Islamic Republic, especially the lengths ordinary people had to go to create private lives for themselves and for their families that were separate from the power and surveillance of the state.

As you know, over the last several months, Iranians have been protesting in huge numbers to push back against the Islamic Republic and its oppressive policies. Something like a video ban may seem insignificant — just something that people had to put up with and navigate around — but the culmination of many laws and policies like this one have become untenable for people, who simply want to live their lives without the encroachment of the state at every turn.

Blake Atwood is Associate Professor of Media Studies at the American University of Beirut and the author of “Reform Cinema in Iran” (Columbia University Press) and “Underground.”