The Patterning Table That Changed My Life

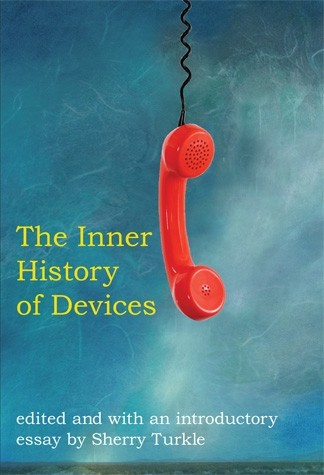

For more than two decades, Sherry Turkle has challenged our collective imagination with her insights about how technology enters our private worlds. The moving essays in “The Inner History of Devices,” edited and introduced by Turkle, bring together writings about devices that come supplied with sanctioned ways of understanding them — objects ranging from cell phones to prosthetic eyes, from televisions to dialysis machines. By taking time to go further, its authors reveal how what we make is woven into our ways of seeing ourselves, often finding what they did not know they were looking for.

In Adriana Knouf’s essay, featured below, a medical device, in its presence and absence, allows her to dream. Faced with her sister Robin’s illness — the gravely debilitating Rett Syndrome — Knouf and her family learn of a technique that offers some hope. The family moves Robin’s limbs rhythmically in crawling and walking movements on a specially built patterning table. While Robin lives, Knouf is immersed in the community around the table. After Robin dies, the table’s absence opens a reflective space for Knouf to consider how it shaped her life. “With Robin,” says Knouf, “the volunteers, the discredited therapy method, and the patterning table, we had tried to awaken cognition with care, with the soft sheepskin, the men and women gathered around.” But the table has stood in the way of many things, and it takes her time to find her way after Robin and the table are gone. With loss, Knouf is able to re-integrate the past.

Our basement walls were covered with charts, schedules, and sets of instructions. In the southeast corner stood the patterning table. Made when I was eight years old by a friend of the family who lived in a nearby town, the patterning table came up to my chest. Supported on its four corners by thick wooden legs attached with massive bolts, the highly varnished table was strong enough for a 50-to-80 pound person to be moved around on its flat surface. That surface was padded with Naugahyde, which in turn was covered by sheepskin that fitted snugly around the edges.

At this table, every Monday through Saturday, three people (five, if we were training new volunteers) surrounded my sister, Robin. We gently took hold of her fragile arms, legs, and head. With a regular rhythm we moved her extremities in the motions of a crawl: one, turn the head to the left, bring the left arm away from the body and next to the head, bend the left leg next to the torso, and vice versa for the right side; two, keep the head where it was, pull the right arm back next to the body, extend the left leg, and vice versa for the right side; three, repeat as one, but switching left for right; four, repeat as two, but switching left for right. One, two, three, four, the count continued over the course of five minutes, and the patterning session was done, for this hour. The ding of a kitchen timer told us it was time to move on. Next hour we repeated it, on the same table with the same sheepskin cover, with different volunteers. All day this continued, according to the schedules, instructions, and charts that my mom wrote in thick strokes on butcher paper and taped to our recently sheetrocked basement walls. Patterning was combined with breathing exercises, using a mask designed to increase the blood flow to Robin’s brain.

When I was in first grade Robin was diagnosed with Rett Syndrome, a rare neurological disorder that may include devastating mental and physical symptoms. It afflicts only girls, most of whom are not expected to live past their 18th birthday. The girls often make rocking motions while sitting, wringing their hands. Many are able to develop some basic level of functioning, such as simple mobility or being able to feed themselves. Robin, however, could do none of these things; she was utterly dependent on us. Even so, there were still the smiles, tears, and frowns of any young girl, and in her eyes you could see thoughts she could not speak.

There were still the smiles, tears, and frowns of any young girl, and in her eyes you could see thoughts she could not speak.

Robin’s disease led our family to take on a major commitment: a full-time, in-home physical therapy program. Our location, rural Iowa, meant we had to develop everything ourselves. To build the equipment, to schedule the people who came in on a regular basis, week after week, we found volunteers, some local, some from afar.

The patterning table took up a good part of our basement, but at a certain point during Robin’s therapy we set up another apparatus for her, a jungle-gym-like contraption made by the same volunteer who built the patterning table. The new contraption reached from the floor to our seven-foot ceiling. The height of the jungle-gym bars was adjustable. At certain times the overhead bars were low enough so that Robin could walk her hands along them. When she was stronger, the bars were raised and Robin had to grab onto freely swinging handholds of thick nylon rope that hung from the bars; she wore specially designed Velcro footies that stuck to our short-pile institutional carpeting. The resistance from the Velcro was meant to make it harder for her to lift her foot, while the swinging rope was meant to improve her sense of balance. It was hoped that this would strengthen Robin’s legs and upper body in preparation for walking on her own.

Our work at the patterning table was based on the Doman-Delacato method. It laid out a series of therapies designed to help brain-damaged children toward better functioning. The method is based on an evolutionary metaphor: The individual develops in their lifetime just as the human evolved over generations. That is, development begins at the fish and reptilian stage (crawling) and moves through to mammals and primates (creeping, with the stomach off the ground). Doman-Delacato reasons that if you “pattern” a brain-damaged child with the motions that are involved in each of these stages, you will unlock the later stages of development. So the repetitive motions on the patterning table were supposed to teach Robin’s muscle memory to crawl. Yet she never was able to crawl on her own: She learned only to walk a step or two, lightly aided.

The Doman-Delacato method reasons that if you “pattern” a brain-damaged child with the motions that are involved in each of these stages, you will unlock the later stages of development.

The Doman-Delacato method has not found empirical support, and the American Academy of Pediatrics has issued a number of warnings about the technique over the years. As a child I never questioned our program. To me, it seemed natural that if we moved Robin’s arms and legs in a certain manner, we eventually would “train” her brain to move body parts on its own. And of course my parents, like so many others, seized on the program’s marketing and the bits of anecdotal evidence that suggested it worked. The Doman-Delacato method provided hope, but I think back on it now with sadness, regret, anger, and resignation.

Robin began to experience seizures when I was in fifth grade, not unusual for Rett girls who often regress from their developmental plateau. I remember the huge stuffed rabbit that lay on the table the day Robin was rushed to the hospital because of her first, unexpected seizure. The seizures made it impossible to continue with the treatments on the patterning table. Yet the patterning table remained in the basement. We removed the sheepskin, and then the Naugahyde quilting, and used the table as any other flat surface, a place to store papers, books, and mail. Gradually the schedules and charts on the butcher-block paper began to come off our walls, but the patterning table remained, a reminder of what we had done, of what we had tried to do.

Even as a young child, I read the few journal articles our family had about Rett Syndrome. They were over my head, but I persisted in my efforts to figure out what was going on with my sister. I launched into my parents’ popular science book on genetics. A year or two before I took any proper biology class, I was discovering genotypes, phenotypes, and karyotypes, the genetic bases of diseases such as sickle-cell anemia and Parkinson’s. At the time, the Human Genome Project was in its nascent stages and the hope for “miracle” cures was strong. With the insufficient knowledge I had, and bolstered by the arguments in the genetics book, I believed that finding the gene or genes that “caused” her disease would lead immediately to gene therapy that would “reverse” Robin’s genetic malfunction. Of course you had to have a way to get the genes into the cells, so I eagerly read about techniques to force the existing chromatin to take up new genetic material—retroviruses and exotic “electro gene therapy.” Then came the problem of how to reverse the damage in existing cells. Neuron regrowth in the brain is meager at best; there, repairing genes would not be enough.

The Doman-Delacato method provided hope, but I think back on it now with sadness, regret, anger, and resignation.

As a middle school student growing up with my sister, I thought these problems surmountable. And I determined that all of this would be my doctoral work: I would find the gene that caused Rett Syndrome and discover the necessary therapies to cure the disease. It was merely a matter of time. The summer before high school, I enrolled in a summer program in molecular biology at the state university, a first chance to work with the tools I had read about: restriction enzymes, plasmids, and ethidium bromide stains. I was in the throes of passion: I pored over books I could not understand; I persuaded other students to work unattended in laboratories full of dangerous reagents. I was in a hurry.

But Robin died in the fall of 1993, just short of her ninth birthday. I sunk into a world of grey and black, my schoolwork the only thing that kept me going. I remember the rush to finish assignments in my high-school biology course that were late because of Robin’s funeral and the time I took off after her death. I remember the fleeting thought that if I could complete my work faster, I could start college early and be on my way to finding the cure for other Rett girls.

I went to Caltech as an undergraduate to study molecular biology with one sole objective in mind: to find a cure for Robin’s disease. In high school I had performed in a chamber music group and had notions about attending a conservatory. I devoured literature and thought about being an English major and studying philosophy. But now, stronger than all of these were my memories of Robin and the patterning table. I was driven to discover the gene for Rett syndrome. I saw it as an achievable goal.

Then, on a gray California winter day during my sophomore year, I read that a group of researchers had discovered the gene responsible for Rett Syndrome. I posted the article outside my room. I told all of my friends. I wanted to be among the people in the article. But there was more work for me: turning the genetic discovery into a treatment for Rett patients. Soon after, experience as a research assistant convinced me that I was not suited for the biology workbench. I moved toward cognitive sciences, with its higher-level descriptions of perception, action, and emotion.

The patterning table, long unused even during Robin’s life, was finally removed from our basement, probably passed on to another family using the Doman-Delacato method. Its absence left a space. I had passed the patterning table and its volunteers in the early morning; I had looked toward it when I came home from school; I had walked to it when it was my turn to be part of the group that moved Robin’s head, legs, and arms.

The table was more than a focus for our thoughts; it anchored our love for Robin and the energy we put into giving her a future.

Without the steady presence of the table, where would we turn? Where would our efforts be channeled? Without Robin’s influence, what would be our purpose? The table was more than a focus for our thoughts; it anchored our love for Robin and the energy we put into giving her a future. Like the tables in traditional Midwestern churches or cafes, the volunteers who assembled chatted and gossiped and spoke about their lives. It brought Robin into a community. When Robin was happy and obedient, her attendants gave her praise; when she was cranky and ornery, they understood, but lightly scolded. The patterning table made life coherent, all of a piece. With Robin, the volunteers, the discredited therapy method, and the patterning table, we had tried to awaken cognition with care, with the soft sheepskin, the men and women gathered around.

Postscript:

I originally wrote this in 2005, and in the interim there has been a tremendous increase in research on Rett Syndrome in light of the gene discovery. I have moved away from cognitive science and into media arts and design, yet I still draw upon the scientific, social, and emotional experiences written about here in my work. Finally, this was written from the perspective of an assigned-male-at-birth person, however I have recently come out as a transgender woman. The experiences with Robin, the volunteers, and my family have all contributed to making me the woman that I am.

Adriana Knouf is an Assistant Professor of Art + Design in the Department of Art + Design in the College of Arts, Media, and Design at Northeastern University in Boston, MA.