The Myth of a Wilderness Without Humans

One way to guarantee a conversation without a conclusion is to ask a group of people what nature is.

—Rebecca Solnit

In the course of “preserving the commons for all of the people,” a frequently stated mission of national parks and protected areas, one class or culture of people, one philosophy of nature, one worldview, and one creation myth has almost always been preferred over all others. These favored ideas and impressions are at some point expressed in art. And it is through art that our earliest preconceptions and fantasies about nature are formed.

They and their friends who sought to preserve an idealized version of nature called it “wilderness,” a place that humans had explored but never altered, exalted but never touched. It was the beginning of a myth, a fiction that would gradually spread around the world, and for a century or more drive the conservation agenda of mankind.

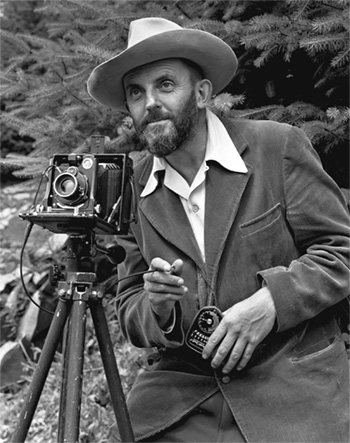

The mystique of Yosemite, for example, was largely created by photographers like Charles Leander Weed, Carleton Watkins, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston, all of whose magnificent images of the place are completely bereft of humanity or any sign of it having been there. Here, they said (and they all knew better) is an untrammeled landscape, virgin and pristine, not a bootprint to be seen, not a hogan or teepee in sight. Here in this wild place one may seek and find complete peace.

They all knew better, the portrayers of wilderness; in fact, Adams assiduously avoided photographing any of the local Miwok who were rarely out of his sight as he worked Yosemite Valley. He filled thousands of human-free negatives with land he knew the Miwok had tended for at least four thousand years. And he knew that the Miwok had been forcibly evicted from Yosemite Valley, as other natives would later be from national parks yet to be created, all in the putative interest of protecting nature from human disturbance.

One can be fairly certain that Weed, Watkins, Adams, and Weston had all at one time in their lives read George Perkins Marsh’s 1864 classic “Man and Nature” and recalled Marsh arguing passionately for the preservation of wild virgin nature, which he said was justified as much for artistic reasons as for any other. Marsh also believed that the destruction of the natural world threatened the very existence of humanity. We know that Muir read Marsh and so did Teddy Roosevelt. They both say so in their journals and memoirs. So when the topic of a park in Yosemite came up Muir and Roosevelt were, so to speak, on the same page.

Dueling Sciences

Natural science is just one way of understanding nature.

—Bill Adams, Cambridge University

The Yosemite model of conservation, which still expresses itself in a fairly consistent form, has sparked a worldwide conflict between two powerful scientific disciplines: anthropology and conservation biology. These two august sciences remain at odds with one another over how best to conserve and protect biological and cultural diversity, and perhaps more perplexing, how best to define two of most semantically tortured terms in both their fields — nature and wilderness.

Cultural anthropologists spend years living in what many of us would call “the wild,” studying the languages, mores, and traditions of what many of us would call “primitive peoples.” Eventually the anthropologists come to understand the complex native cultures that keep remote communities thriving without importing much from outside their immediate homeland.

“We do not ask if indigenous peoples are allies of conservation or what sort of nature they protect,” write Paige West and Dan Brockington, two anthropologists who have spent most of their careers researching the impact of protected areas on indigenous cultures; “instead we draw attention to the ways in which protected areas become instrumental in shaping battles over identity, residence and resource use.” Their experience has convinced them that the best way to protect a thriving natural ecosystem is to leave those communities pretty much alone, where and as they are, doing what they’ve done so well for so many generations — culturing a healthy landscape, or what development experts would call “living sustainably.”

Wildlife biologists also spend much of their careers in remote natural settings, but tend to prefer landscapes void of human hunters, gatherers, pastoral nomadics, or rotational farmers. They find anthropologists somewhat “romantic” about indigenous cultures, particularly tribes that have become partly assimilated and modernized; which generally means the tribes are in possession of environmentally destructive technologies such as shotguns, chainsaws, and motorized vehicles, conveniences that Western naturalists know from their own civilization’s experience can wreak havoc on healthy ecosystems.

“The time has come to rethink wilderness,” wrote environmental historian William Cronon in 1995.“Wilderness stands as the last remaining place where civilization, that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth.”

These two disciplines are also at odds over what they mean by nature and the degree to which humanity is part of it. And they have a different sense of wildness and wilderness. It is in this regard that one is more likely to hear anthropologists calling naturalists “romantic.” Listening to this exchange of insults one might conclude one is witnessing a clash of romantic tendencies.

William Cronon, an environmental historian at the University of Wisconsin, has spent much of his intellectual career grappling with these conflicts. His thinking on the subject eventually came together in 1995 with publication of a widely read and controversial essay titled “The Trouble with Wilderness, Getting Back to the Wrong Nature.”

“The time has come to rethink wilderness,” Cronon begins his essay. He goes on to challenge the widely held and decidedly romantic notion of environmentalists that “wilderness stands as the last remaining place where civilization, that all too human disease, has not fully infected the earth.” That concept, Cronon believes, gives credence to “the illusion that we can somehow wipe clean the slate of our past and return to the tabula rasa that supposedly existed before we began to leave our marks on the world.” That fiction, which Cronon believes is based on a profound misunderstanding of nature, and our place in it, creates a force that is antagonistic to conservation. “The myth of wilderness,” he writes, “is that we can somehow leave nature untouched by our passage.” He goes on to challenge the shopworn and often misunderstood shiboleth of Henry David Thoreau that “in wildness is the preservation of the world.”

Cronon concludes: “The more one knows of its peculiar history, the more one realizes that wilderness is not quite what it seems. Far from being one place on earth that stands apart from humanity, it is quite profoundly a human creation — indeed, the creation of very particular human cultures at very particular moments in human history. It is not a pristine sanctuary where the last remnant of an untouched, endangered, but still transcendent nature can for at least a little while longer be encountered without the contaminating taint of civilization. Instead, it is a product of that civilization.”

These are fighting words to a “civilization” that has set millions of square miles of valuable land aside as “wilderness,” passed a national law — the 1964 Wilderness Act — to both define and protect wilderness, and still supports a dozen or so well-heeled national organizations to lobby for more wilderness set-asides and convince the public that figuratively walling off large expanses of unoccupied land is the only way to preserve nature and biological diversity. But how natural is wilderness? To Cronon, not as natural as it seems.

By glorifying pristine landscapes, which exist only in the imagination of romantics, Western conservationists divert attention from the places where people live and the choices they make every day that do true damage to the natural world of which they are part.

“Wilderness hides its unnaturalness behind a mask that is all the more beguiling because it seems so natural,” he says. By glorifying pristine landscapes, which exist only in the imagination of romantics, Western conservationists divert attention from the places where people live and the choices they make every day that do true damage to the natural world of which they are part.

So the removal of aboriginal human beings from their homeland to create a commodified wilderness is a deliberate charade, a culturally constructed neo-Edenic narrative played out for the enchantment of weary human urbanites yearning for the open frontier that their ancestors “discovered” then tamed, a place to absorb the sounds and images of virgin nature and forget for a moment the thoroughly unnatural lives they lead.

So What is Wild?

What counts as wilderness is not determined by the absence of people, but by the relationship between people and place.

—Jack Turner, philosopher

On several occasions during my research, an interview would be brought to a dead stop after I included the word wild or wilderness in a question. The word simply didn’t exist in the dialect of the person I was interviewing. My interpreter would stare at me and wait for a better question.

When I tried to explain what I meant by wild to Bertha Petiquan, an Ojibway woman in northern Canada whose daughter was interpreting, she burst out laughing and said the only place she had ever seen what she thought I was describing as wild was a street corner outside the bus station in Winnipeg, Manitoba.

In Alaska, Patricia Cochran, a Yupik native scientist, told me “we have no word for ‘wilderness.’ What you call ‘wilderness’ we call our back yard. To us, none of Alaska is wilderness as defined by the 1964 Wilderness Act — a place without people. We are deeply insulted by that concept, as we are by the whole idea of ‘wilderness designation’ that too often excludes native Alaskans from ancestral lands.” Yupiks also have no word for biodiversity. Its closest approximation means food. And the O’odham (Pima) word for wilderness is etymologically related to their terms for health, wholeness, and liveliness.

“To us, none of Alaska is wilderness as defined by the 1964 Wilderness Act — a place without people. We are deeply insulted by that concept, as we are by the whole idea of ‘wilderness designation’ that too often excludes native Alaskans from ancestral lands.”

Jakob Malas, a Khomani hunter from a section of the Kalahari that is now Gemsbok National Park, shares Cochran’s perspective on wilderness. “The Kalahari is like a big farmyard,” he says, “It is not wilderness to us. We know every plant animal and insect, and know how to use them. No other people could ever know and love this farm like us.”

“I never thought of the Stein Valley as a wilderness,” remarks Ruby Dunstan, a Nl’aka’pamux from Alberta. “My Dad used to say ‘That’s our pantry.’ Then some environmentalists declared it a wilderness and said no one was allowed inside because it was so fragile. So they put a fence around it, or maybe around themselves.”

The Tarahumara of Mexico also have no word or concept meaning wilderness. Land is granted the same love and affection as family. Ethnoecologist Enrique Salmon, himself a Tarahumara, calls it “kincentric ecology.” “We are immersed in an environment where we are at equal standing with the rest of the world,” he says. “They are all kindred relations — the trees and rocks and bugs and everything is in equal standing with the rest.”

When wildness is conflated with wilderness, and wilderness with nature, and nature is seen as something separate and uninfluenced by human activity, perhaps it’s time to examine real situations and test them against the semantics of modern conservation. Are Maasai cattle part of nature? Perhaps not today, but when they wandered through the open range by the thousands, tended by a few human herdsman whose primary interest was to keep the biota healthy for their livestock and other wildlife, one might say they were “wild,” certainly as wild as the springbok, eland, elephant, and buffalo that daily leave the open pasture to ravage Maasai farms for fodder.

And Who Is Nature?

We forget the reciprocity between the wild in nature and the wild in us.

—Jack Turner, philosopher

In one of the many conversations about nature I have been part of over the past three years, I said to a man — an educated, erudite, and generous supporter of international conservation, whose view of nature differed considerably from my own — “You are nature.” He looked at me and laughed nervously. I had not insulted him, he assured me. He just didn’t appreciate the notion that he was part or product of a system that also created “snails, kudzo, mules, earthquakes, grizzly bears, viruses, wild- fires, and poison oak.” It turned out also that his younger sister had, years before, been badly mauled by a mountain lion.

Well, how do you convince someone with that experience that he is kin with the lion? Perhaps you can’t, I thought, but he seemed interested in continuing the conversation. Others joined in, and by the end of the evening he had accepted himself as an equal in the same creation with the lion that mauled his sister, a creation he was willing to call “nature,” a creation of which he was not apart, but a part.

When one perceives humanity to be something separate from nature it becomes easier to regard landscapes in their “natural state” as landscapes without human inhabitants and aspire to preserve wilderness by encouraging the existence and survival in landscape of as many species as possible, minus one — humans.

The valuable contribution anthropology has made to conservation is perhaps best expressed by Paige West and Dan Brockington, who advise conservationists to be more aware of “local ways of seeing,” and that the practice of conservation will be more successful “if practitioners learn local idioms for understanding people’s surroundings before they begin to think about things in terms of nature and culture.” There is a need, they say, for conservationists “to grasp the complicated ways that people interact with what they rely on for food, shelter, as well as spiritual, social and economic needs.”

Enrique Salmon believes that “language and thought works together. So when a people’s language includes a word like ‘wilderness,’ that shapes their thoughts about their relationship to the natural world. The notion of wilderness then carries the notion that humans are bad for the environment.”

Certainly someone who regards the forest as his “pantry” is going to see the flora, fauna, soil, and water in a somewhat different light than the tourist, biologist, miner, or logger. But is there not something that can be seen by all of them, some common ground on which the forest’s intrinsic value can be considered and agreed upon?

Anthropologist Enrique Salmon believes that “language and thought works together. So when a people’s language includes a word like ‘wilderness,’ that shapes their thoughts about their relationship to the natural world.”

One example of a very different local idiom that Western naturalists have difficulty understanding is that of the Gimi, one of the hundreds of remote, Stone Age cultures in central Papua New Guinea. The Gimi “have no notion of nature or culture,” say West and Brockington. “They see themselves in an ongoing set of exchanges with their ancestors [who they believe are] animating and residing in their forests, infusing animals, plants, rivers, and the land itself with life. When people die their spirits go back to the forest and infuse themselves into plants, animals and rivers. When the living use these natural resources they do not see it as a depletion but rather as an ongoing exchange” of energy and spirit.

When the Gimi kill and eat an animal “they understand it to be generated by their ancestors’ life forces and it will work to make their life force during this lifetime. When they die that force will go back to the forest and replenish it.” This is an admittedly difficult cosmology for the Western mind to contemplate or accept. But the fact that every atom in every living thing has existed since the beginning of time gives some scientific grounding to the Gimis’ belief that spirit is simply reorganized force and matter. That said, their understanding “of the relationship between humans and their surroundings [remains] extremely difficult to reconcile with arguments about the decline and loss of biological diversity.”

However, if Western conservationists in central Papua New Guinea know that the Gimi believe all matter is here for eternity, that it simply changes form over time, they will be better equipped to work with local communities in the preservation of biodiversity. But if they dismiss that cosmology as primitive animism and seek to impose Western science and religion on the Gimi people, their conservation initiative will almost certainly fail.

Of course, the final arbiters in this scientific conflict should be indigenous peoples themselves, the very people that early advocates for Yellowstone Park said had no interest in raw nature or the park area. They were alleged to be afraid of the geysers and fumaroles (Not true. They cooked over them). The truth is that much of what the rest of us know about nature and have incorporated into the various sciences we use to protect it — ecology, zoology, botany, ethnobotany — we learned from the very people we have expelled from the areas we have sought to protect.

Mark Dowie is an award-winning journalist and former publisher and editor of Mother Jones magazine. He is the author of several books, including “Conservation Refugees,” from which this article is excerpted.