The Lulz of Medusa: On Laughter as Protest

The physical act of laughter is the ultimate tool of playful protest. It does not require props, screens, or any affiliated costs. Laughter has the ability to disrupt the status quo, extricating stifling hypocrisies. It is always available, regardless of your position of power. It works as an antiseptic and is clarifying. It is personal. Laughter has been used and mobilized by those in the past, and needs to reclaim its role in the protestations of the future. Laughter is a striking tool of resistance. If deployed properly, we can giggle, guffaw, chuckle, and snicker toward resistance and advancement.

But how do we laugh in the face of the terrible things that happen — things that strike us so deeply that we are immobilized with fear? In these moments, our first response to protest is often one of anger and deliberate, obstinate resistance. When this anger turns into overwhelming sadness, how do we locate the presence of mind to laugh without diminishing or undercutting our topic?

When I wrote about protest and laughter in my book, “Play Like a Feminist,” I wrote it in the shadow of a shooting in 2018, when 11 people were shot at a synagogue in Pittsburgh. Like so many other shootings, this story feels unremarkable, with fresh gun violence occurring as frequently as our hearts beat. Last month, a gunman killed eight people in Atlanta, most of them women of Asian descent. Not a week later another killed 10 shoppers in Boulder. In the face of this, how do I find space for laughter? This year alone, there have already been 104 mass shootings recorded in the United States of America. How do any of us find space for laughter?

I laugh because laughter is power. Rebecca Krefting refers to “charged humor”: a form of disruptive laughter meant to reimagine communities and use comedy to “foment social change.” Krefting observes that in this way, laughter is an inroad toward social justice. Similarly, historian Joseph Boskin writes about the ability of comedy to disrupt the momentary zeitgeist and offset power. But he also suggests that political humor is often deployed ineffectively, and that rather than focusing on institutions, it tends to be directed at individuals. In other words, the target of derisive laughter should not be the politician who makes a public misstep but instead the political system that put that politician in power. This lack of institutional focus makes our laughter less effective as a weapon.

Nevertheless, laughter has been and can be weaponized. Charged humor, in addition to being a kind of communal glue, is personal and intimate. We can laugh in a crowded theater, to great satisfaction, but we can also laugh alone and unheard by others. Laughter can be deployed by the disenfranchised to reclaim their sense of the absurd world we live in while remaining a binding substance that can fortify relationships. We need more laughter.

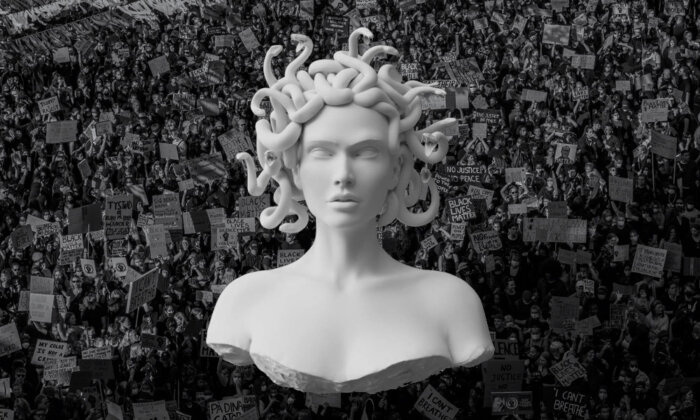

Medusa’s laughter is rebellious; it fights back against the gods and mortals who have left her in her predicament.

Famously, in her essay “The Laugh of Medusa,” Hélène Cixous writes about the monstrous feminine as inhabited by the infamous mythological icon. Rather than casting her as a beast, Cixous reinterprets the character, noting, “You only have to look at the Medusa straight on to see her. And she’s not deadly. She’s beautiful and laughing.”

Medusa’s laughter is rebellious; it fights back against the gods and mortals who have left her in her predicament, and it is our own fear that keeps us from hearing that laughter. It is Medusa’s laugh that we need to model in an attempt to play like feminists. Our laughter needs to be binding yet personal, light yet serious, and it needs to attack the institutional structures that sit expressionless and immovable.

In order to find Medusa’s laughter, perhaps we should reconsider it as a kind of lulz. The term “lulz” was originally adopted by internet trolls; Whitney Phillips, in her book on online trolling, defines it as “amusement at other people’s distress.” This vision of lulz, unto itself, might seem categorically negative and nonproductive. Others have described it in not quite so deleterious terms; Jessica Beyer refers to it as “entertainment for entertainment’s sake,” which parses as far less nasty than implied by Phillips’s definition. Phillips further suggests that the actual deployment of lulz are necessarily fetishistic (they are decontextualized into exploitable details), generative (lulz beget more lulz), and magnetic (they create communities), altogether constructing an “emotional gap between those who laugh and that which is laughed at.” Lulz seem to teeter between these definitions that place them as mean in spirit and chaotically neutral. Yet they also have the capacity to build across communities and upend patriarchal structures. Digital communication scholar Amber Davisson argues that in internet culture, lulz have replaced ideology in order to create networks. Internet trolls are not the only ones who can use lulz to these ends.

Lulz have indeed been used by anonymous internet trolls to disrupt the status quo of institutional structures. Famously, the multifaceted attacks on Scientology organized by Anonymous are a good representation of this kind of playful, lulzy, protesting behavior. While the reputation of internet lulz tends to focus on the individual takedown, there are many examples of lulzworthy attacks on larger political systems, corporations, and organizations (see, for example, Adrienne Massanari’s research on the subreddit r/TrollXChromosomes). The magnetism and generative nature of lulz means that it becomes easy to turn the laughter of one into the lulz of many. While the fetishism of lulz removes context, this lack of context also allows for the faster spread of meme-like protest. Lulzing is not always out-loud laughter, but it is loud and powerful. Laughter is contained, but lulz can echo.

I imagine Medusa typing furious tweets that mock the gods who abandoned her rather than just the humans who attacked her.

When I first read Cixous’s writing about Medusa’s laugh, I always had an image of a singular monstress, alone in her cave, laughing quietly to herself about the foolish men who came to claim her head. Medusa’s laugh in this version seems solitary, lonely, and almost desperate. But if Medusa were to lol rather than laugh, she would gain the power of many. She would be able to stare down the internet, wreaking havoc with her laughter through networks. Medusa no longer sits in solitude; she uses her laughter to reclaim community, identity, and purpose. In this new version, I imagine Medusa typing furious tweets that mock the gods who abandoned her rather than just the humans who attacked her.

How do I find space for laughter? The answer is not laughter but rather the lulz of Medusa.

We live in dark times. Our natural resources are depleting. There is global unrest and abuse of power. Fascists and dictators reign around the world. While some have plenty, others go without basic needs to survive. There are too many guns owned by people who embrace hate as a part of their identities. We need to protest these things, but we need to do a better job at getting noticed, being heard, and evoking global change. To do this, it is time for feminists to find more room for play and laughter in the fight.

Shira Chess is Associate Professor of Entertainment and Media Studies at the University of Georgia and author of “Ready Player Two” and “Play Like a Feminist,” from which this article is adapted.