Birthing Furniture: An Illustrated History

The benefits of various birthing positions — kneeling, standing, sitting, squatting, or lying down — particularly with regard to pelvic posture, have been publicly debated at least since the 1880s.1 Birthing positions can be chosen or mandated, intuited or inherited, self-directed or at the behest of other forces. Birthing furniture and other physical objects, structures, and accoutrements determine not only the physiology but also the emotional experience of birth.

In what follows, we mine medical manuals, period magazines, centuries-old etchings, and contemporary speculative designs to trace how birthing positions, furniture design, and social and cultural expectations have split and converged over time. Even in a single environment, birth furniture (and birthing positions) can vary dramatically, from the supine position a birthing bed facilitates to the more active, interchangeable, and spontaneous positions that equipment like yoga balls and peanuts, slings, bars, stools, pools, and chairs make possible. Some designs, such as birth shackles, may seem anachronistic but are still routinely used on incarcerated people, both while they give birth and postpartum. Even without any furnishings, birthing people find their way. In a bas-relief dating to about 60–30 BCE at the Temple of Esneh in Egypt, for example, Cleopatra is depicted giving birth in a kneeling position, her body surrounded and supported by other women.

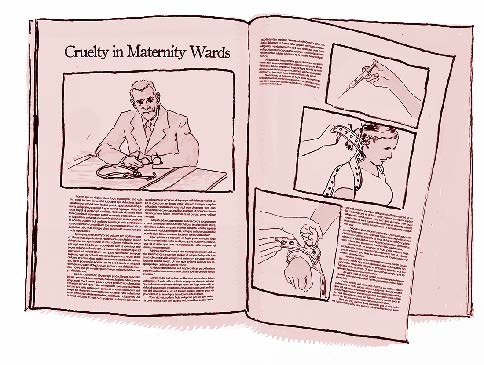

The May 1958 Issue of the Ladies Home Journal

In this issue of the popular women’s magazine, among the usual representations of midcentury motherhood — gleaming appliances, cake recipes, and lipstick-wearing women in aprons — was a page with a letter penned by an anonymous labor and delivery nurse:

When I first started in my profession, I thought it would be wonderful to help bring new life into this world. I was and am still shocked at the manner in which a mother-to-be is rushed into the delivery room and strapped down with cuffs around her arms and legs and steel clamps over her shoulders and chest. It is common practice to take the mother right into the delivery room as soon as she is “prepared.” [This preparation would have meant shaved pubic hair and an enema.] Often she is strapped in the lithotomy position, legs in stirrups with knees pulled far apart, for as long as eight hours. On one occasion, an obstetrician informed the nurses on duty that he was going to a dinner and that they should slow up things. The young mother was taken into the delivery room and strapped down hand and foot with her legs tied together.2

The letter touched a nerve. Women across the country wrote in to share their own stories of abuse, including being strapped down and drugged in an effort to keep them still, quiet, and passive.3

Birthing Beds and Tables

The recommendation to give birth while lying down was, at least at first, well intentioned. It was formally introduced in 1598 by the French barber-surgeon Jacques Gillemeau, who claimed reclining was most comfortable and would help induce labor. The first birthing beds were actual beds, similar to furniture for sleeping. In the mid-1800s, medical designers added leg harnesses and stirrups to obstetric tables, which soon carried over to the design of birthing beds, as did leather straps and other restraints.4 With the invention of plastics, birthing beds could be made lightweight, easily cleaned and assembled, and adjustable.

Though there were no uniform obstetric practices until the first quarter of the twentieth century, the dorsal position (lying flat on one’s back) and the lithotomy position (lying back with one’s feet in stirrups) became biomedical birthing standards in hospitals.5 Many types of birthing beds fold the birthing person into an upright position, inviting the power of gravity into the design.

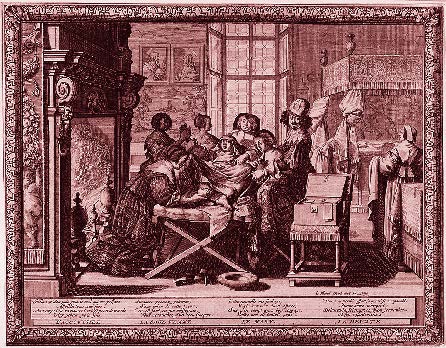

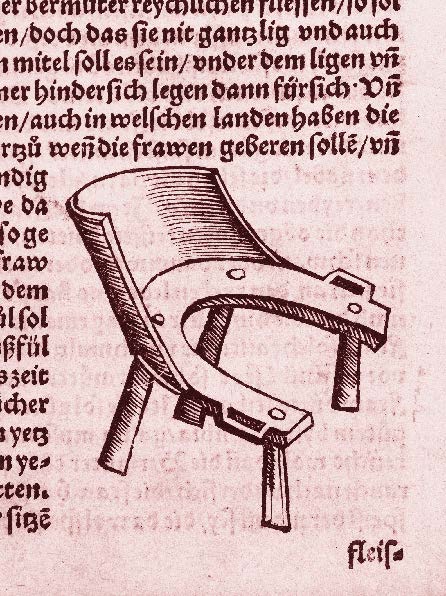

Birthing Chairs and Stools

Birth chairs and backless birthing stools help people feel balanced and supported in an upright position as they give birth. With three or four legs, they usually feature a semicircular cutout on the seat. The position of the body in the birthing chair not only makes use of gravity as the baby drops from the womb and emerges through the vagina, but also maximizes the ability of muscles (abdominal, back, stomach, legs, arms, and vaginal sphincter) to efficiently work in concert. Babylonian birthing chairs date back to 2000 BCE. An Egyptian wall relief dating to 1450 BCE in the birth room of the Luxor temple shows Queen Mutemwia giving birth to her son, Amenhotep III. A birthing chair is also depicted on a Greek votive from 200 BCE.6 Some millennia-old birthing stools from Britain were designed to be carried while disassembled, suggesting that they belonged to midwives rather than individual house- holds. Today, many birthing centers incorporate furniture and accoutrements made for sitting and squatting while in labor. The woodcut above shows a birthing stool from Der schwanngeren Frawen und Hebammen Rosengarte, by the German physician Eucharius Rösslin. First published in 1513, it became a standard midwives manual in Germany.

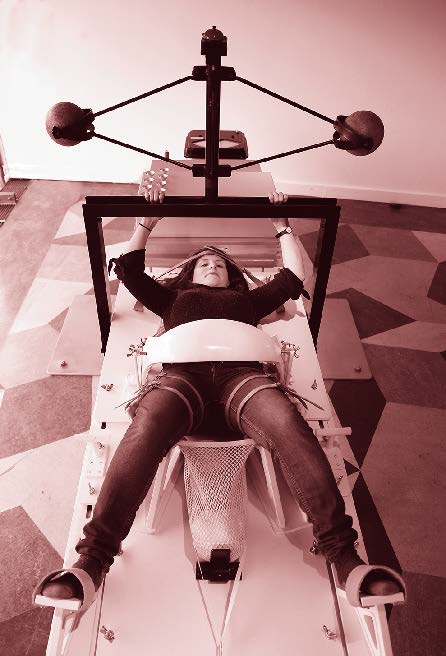

The Blonsky

In 1965, New Yorkers George and Charlotte Blonsky were granted a patent for an “Apparatus for Facilitating the Birth of a Child by Centrifugal Force.” The circular table was meticulously engineered and incorporated safety features designed to protect both mother and child. When it was time to give birth, a mother would be instructed to lie on her back with her legs open; she would then be strapped into place and the table would be rotated at very high speed. To prevent the infant from flying out, a soft mesh net was there to catch it. The design would “assist the under-equipped woman by creating a gentle, evenly distributed, properly directed, precision-controlled force, that acts in unison with and supplements her own efforts.”7 Though lovingly and elaborately designed with only the best intentions, the Blonsky never made it to general use. This version was presented by the artist Marc Abrahams in the exhibition Fail Better at the Science Gallery at Trinity College Dublin in 2014.

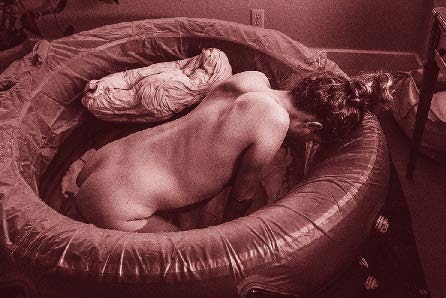

Birthing Pools

While midwives from around the world have used water in one form or another to help ease pain and relax birthing people, birthing pools are a more recent phenomenon.

Some trace their genesis to Moscow in the 1960s, when Igor Charkovsky, a former swimming instructor and self- described “father of sea births,” encouraged birthing in the Crimean Sea. In the 1970s, Dr. Michel Odent designed a birthing room at the General Hospital in Pithiviers, in northern France. Dark, earthy colors and heavy curtains encouraged a feeling of seclusion and intimacy, enabling birthing people to labor in whatever positions they found most comfortable. In 1977 Odent installed a pool in the room. Though he envisioned water as a form of pain management, many of his patients birthed within the pools, and Odent is often credited with starting the trend of birthing in water.8 The visual image of an uninterrupted flow of liquid can have a powerfully positive psychological effect, and the sense of weightlessness that comes with immersing oneself in water can be used to encourage intuitive movement and postures.

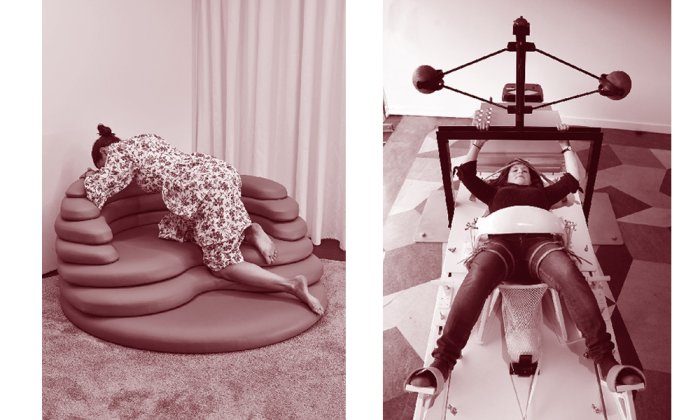

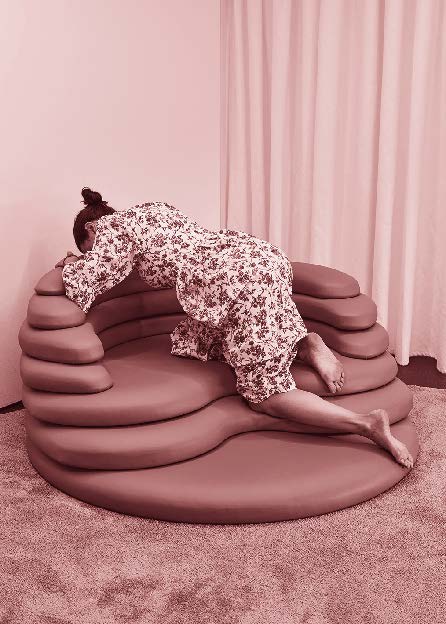

Stiliyana Minkovska’s Ultima Thule

With greater numbers of birthing people and families exercising their right to actively participate in the birth experience, making it more physiologically and psychologically supportive as well as personal, positive, and even profound, designers are responding. In 2020, the Bulgaria-born, UK-based artist and designer Stiliyana Minkovska created Ultima Thule, a speculative design for an otherworldly, sanctuary-like birth environment made up of three flexible, sculptural pieces of birthing furniture. Using color, texture, and open-ended shapes to facilitate a variety of postures, the pieces work as “an aid that allows the pregnant body to adopt any desired position in order to prepare for parturition. The pieces are accommodating, which allows the expectant parent to sit, kneel, squat, rest, lean, and crawl until they find comfort. It is a gradual element, where the mother takes the journey on her own, or can be supported by a partner, doula, or a midwife.”9

Michelle Millar Fisher is a curator and architecture and design historian, is Ronald C. and Anita L. Wornick Curator of Contemporary Decorative Arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. She lectures frequently on design, people, and the politics of things.

Amber Winick is a writer, design historian, and recipient of two Fulbright Awards. She has lived, researched, and written about family and child-related designs, policies, and practices around the world.

Notes:

- Horizontal birthing positions have been used in Western culture for only about two hundred years. Before this, any recorded history of birth shows an upright birthing position. See Lauren Dundes, “The Evolution of Maternal Birthing Position,” American Journal of Public Health 77, no. 5 (May 1987): 636.

- “Cruelty in Maternity Wards,” Ladies’ Home Journal, May 1958, 45; quoted in Tina Cassidy, Birth: The Surprising History of How We Are Born (New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006), 65–66.

- Tina Cassidy, Birth: A History (London: Chatto & Windus, 2006), 66–67.

- Margaret Jowitt, “The Rise and Rise of the Obstetric Bed,” Midwifery Matters 132 (Spring 2012): 16

- J. L. Reynolds, “Primitive Delivery Positions in Modern Obstetrics: Were the Wise Women Wiser Than We?,” Canadian Family Physician (Medecin de famille canadien) 37 (1991): 356–61.

- See Amanda Carson Banks, Birth Chairs, Midwives, and Medicine (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1999), 3.

- US patent 3,216,423, filed January 15, 1963, issued November 9, 1965.

- In 1974 the French physician Frédérick Leboyer published Birth Without Violence, a book that scrutinized the birth environment from the perspective of the baby.

- Stiliyana Minkovska, email to the author, July 15, 2020.