The Brilliant Vision of Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain’s "Sultana’s Dream"

In 1905, Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, who was then most likely between 25 and 28 years old (her exact birthdate is unknown), published the proto-science fiction story “Sultana’s Dream” in The Indian Ladies’ Magazine, a Madras-based English-language periodical edited by and for women. While most of the contributors to this and similar journals published in British India were Hindu, Hossain was Muslim. Even more unusual was her story’s championship of women’s liberation.

Like the story’s author, the narrator of “Sultana’s Dream” practices purdah, whereby women are sequestered in a home’s “zenana” area. Whisked away to a future city-state known as Ladyland, Sultana is at first hesitant to venture into the street. Isn’t it unsafe for women out there? Her host, however, reassures her that she has nothing to fear… because, 30 years earlier, during a war that killed off most of the nation’s menfolk, the surviving males were ordered to isolate themselves indoors, where they’ve remained ever since.

Although the author reassures readers that all this is just a dream, one gets the distinct impression that Sultana’s host — a female scientist — has transported her into the future with the goal of subverting the course of history. This was groundbreaking stuff. Remarkably, Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s novel “Herland,” one of the most influential feminist utopias of the early 20th century — an era I’ve described as science fiction’s “Radium Age” — wouldn’t appear for another 10 years.

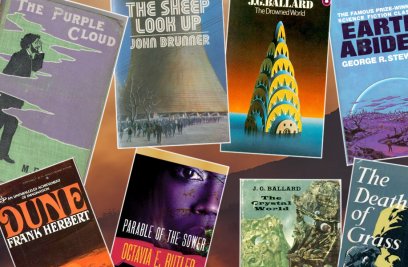

Ladyland, with its two-hour workday, solar technology, and flower-paved streets, all of which is made possible by female scientists and leaders, represents a world in which I, for one, would enjoy living. It’s why I chose “Sultana’s Dream” as the opening story in “Voices from the Radium Age,” a collection of fiction that inaugurated the MIT Press’s Radium Age series of reissued proto-sf stories and novels.

But “Sultana’s Dream” is just one part of Hossain’s rich legacy. Known after her death by the honorific Begum Rokeya (a “begum” is a Muslim woman of high rank), Hossain was born to a well-educated Muslim family in the Bengal Presidency — a subdivision of the British Empire in India now divided into Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal. After the death of her husband in 1909, she would establish India’s first school for Muslim girls — going door to door in an effort to recruit students from reluctant families. In 1911, she’d reestablish the school in Calcutta (now Kolkata). The Sakhawat Memorial Girls’ High School — now run by the West Bengal Board of Secondary Education — is still operating today.

The two-hour workday of Ladyland seems ever less possible for today’s workers, who are not only exploited by their employers but bamboozled into believing that “the hustle” is what gives life meaning.

Having overcome one social, cultural, economic, and political obstacle after another, in 1924 Hossain offered a fictionalized version of her real-life experiences in “Padmarag” (“The Ruby,” or “Essence of the Lotus”), a Bengali-language feminist and anti-colonialist utopian novella set in Tharini’s House — a women-run school, boarding house, and welfare center in Bengal. The staff of Tharini’s House are progressive activists who aim to provide equal opportunities for female students, regardless of their ethnicity, religion, region, class or caste. Moreover, the instructors resist the colonialist dictates of their students’ parents, who wish only for their daughters to “speak fancy,” which is to say, to speak English with a posh accent. All women, whether Hindu, Muslim, or Christian, whether south Asian or European, are victims of oppression, we come to understand as we follow the diverse characters’ various storylines. The best possible remedy to this sorry state of affairs? A nonsectarian, inclusive and self-supporting “arcology” — to use a term popularized more recently by sf authors — directed and staffed by women.

Other Bengali writings of Hossain’s include the two-volume “Matichur” (“A String of Sweet Pearls,” 1904 and 1922), which collects essays first published in magazines such as Saogat, Mahammadi, Nabaprabha, Mahila, Bharatmahila, Al-Eslam, and Nawroz. Here she advocates — deploying logic, imagination, indignation, and a sly wit, as necessary — for men and women to be treated equally, and argues that women’s education is a critical tool for overcoming not only patriarchal social norms but also colonialism, classism, and religious extremism. Yet another work of nonfiction, “Abarodhbasini” (“The Confined Women,” 1931), offers Hossain’s criticism of extreme forms of purdah that, in her account, destroy women’s sense of self and rob them of their humanity.

In 1916 Hossain founded the Muslim Women’s Association, which advocated for women’s education and employment, and via which she advanced a controversial theory that progressive social reforms should be based on the “original teachings” of Islam. In 1926, she presided over the Bengal Women’s Education Conference convened in Kolkata, which has been described as the first significant attempt to bring Indian women together in support of women’s education rights. She remained a fierce champion of the advancement of women until her death in 1932, which occurred shortly after she’d presided over a session of the All India Women’s Conference. To this day, Bangladesh observes Rokeya Day every year on December 9th to commemorate her extraordinary legacy of thought leadership and activism.

I believe it’s instructive to revisit the social ills that concerned Hossain, particularly since we’ve made so very little progress since then. The two-hour workday of Ladyland, for example, seems ever less possible for today’s workers, who are not only exploited by their employers but bamboozled into believing that “the hustle” is what gives life meaning. And forget about flying cars. When will we ever see realized what Sultana glimpses: the abolition of fossil-fuel technologies, the greenifying of cities, the detoxification of masculinity, and the triumph of love and truth over fear and hatred?

Joshua Glenn is a consulting semiotician and editor of the website HiLobrow. The first to describe 1900–1935 as science fiction’s “Radium Age,” he is editor of the MIT Press’s series of reissued proto-sf stories from that period.