The Bizarre Cultural History of Saliva

Life is a continuous flow. In living organisms, there is an unceasing circulation and streaming of fluids with various beneficial, life-promoting effects. The ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus was so strongly impressed by this fact that he made it the leading principle of all his reflections on life. He was not alone.

Bodily fluids ever enjoyed a high prestige as curative agents. Holy Scripture informs us that Jesus’ method of restoring a blind man’s sight included spitting on his eyes, either directly (Mark 8:23) or indirectly, by first preparing a paste of saliva and mud, then anointing the blind person’s eyes with it (John 9:6). It is true that interpreters are quick to point out that Our Savior did this only for the form, so to speak, since divine might had no need to resort to any physical means. But such means He did use, because the people, the Romans, and the Jewish rabbis expected it, saliva being then considered a legitimate agent in ophthalmological therapy.

Considering the magnitude of men’s hubris, it comes as no surprise that some pretended to emulate the divine miracle. The Roman emperor Vespasian (AD 9–79), while touring in Alexandria, spat upon the eyes of a blind man who implored him to do so, allegedly at the prompting he had received in a dream from the Greco-Egyptian god Serapis. Chroniclers tell us that a lame man also came and begged for a cure, asking the emperor to touch with his foot the withered limb. At first, Vespasian shrank from doing either in front of a large crowd, but his doctors advised him to go ahead. This he did, and, to believe the chroniclers, both petitioners were cured.

However, Tacitus, the great Roman historian, remarks that the doctors had previously determined that the blindness of the one was partial, and the lameness of the other only a dislocation. The physicians figured that the emperor had nothing to lose. If the attempt was successful, Vespasian’s prestige would be raised to the skies; if unsuccessful, the sick wretches would be covered with ridicule for asking what was manifestly absurd. Clearly, the universal motto of politicians was then, as now, “Accept all of the credit, none of the blame.”

Ancient Romans spat upon the victim of an epileptic fit, and they spat to ward off the “bad luck that follows meeting a person lame in the right leg.”

Pliny the Elder praises the therapeutic powers of human saliva in his “Natural History” (Book XXVIII, vii). Not only is it the best of all safeguards against serpents, he says, but daily experience teaches that many other advantages attend its use. Surely the ancient Romans were sensitive to such notions: They spat upon the victim of an epileptic fit, and they spat to ward off the “bad luck that follows meeting a person lame in the right leg.” If deemed guilty of too presumptuous hope, they asked forgiveness of the gods by spitting in their own bosom. They spat into the right shoe before putting it on, for good luck; and, of course, they treated ophthalmia by applying a saliva-based ointment every morning. Pains in the neck were treated by applying fasting saliva (interestingly, to be useful the saliva had to be obtained during fasting) with the right hand to the right knee and with the left hand to the left knee. So powerful was the force attributed to saliva, wrote Pliny, that the Romans believed that spitting three times before taking any medicament sufficed to enhance its curative power.

The healing powers of oral secretion kept their good renown throughout history. Albert the Great (Latinized name, Albertus Magnus: 1193–1280), regarded by some as the greatest theologian and philosopher of the Middle Ages, extolled the medicinal properties of human saliva, especially that obtained during prolonged fasting which included abstention from liquids. Its beneficial nature, said the doctor universalis, is reflected in its ability to kill asps and other venomous creatures: It suffices that we spit upon them, or touch them with the tip of a rod that has been wetted with the liquid from our mouth, for all the nefarious vermin immediately to die. This idea did not originate with Albert; it carries echoes of Pliny and his predecessors. However, the medieval sage adds that further proof of the wondrous salivary virtue lies in the observation that wet nurses use their own saliva to cure the newly born of all sorts of cutaneous inflammations, furuncles, and impetigo by rubbing the lesions with their spittle. And he quotes the reports of Arab physicians who affirm that, once mixed with mercury, its therapeutic powers are so greatly enhanced that a victim of the plague may be saved by simply inhaling the mixture’s emanations.

As late as the middle of the 19th century, we find the therapeutic prestige of saliva undiminished. Nicholas Robinson, an English medical author who signs his book simply as “A physician,” extolls enthusiastically the virtues of saliva, which he calls a “recrement.” This word, according to the Oxford English Dictionary, has been in circulation among the English-speaking peoples at least since 1599, with the meaning of “the superfluous or useless portion of any substance,” and is still employed, however rarely, to designate the dross, the unessential.

Our medical author, however, points out that recrements are to be distinguished from excrementitious discharges; the latter are thrown out of the body and are of no further use to it, whereas the former serve many necessary purposes in the life of the organism. Saliva, like pancreatic juice and other fluids, is one of these indispensable “recrements.” But the three “grand recrements of the body are the saliva, bile, and seed,” he writes, for not only do they preserve life and health in the individual, but the last named is “that sacred balsam that has continued the species from the beginning of the world to this time, and which will so continue it to the latest period of nature.”

After this rhapsodic preamble, Robinson enumerates the wonderful therapeutic properties of saliva. As in historical and scriptural precedents, its ability to relieve sore eyes is brought to the fore: Eyelids red, angry, and inflamed are a cause of much distress, but one has only to touch them with a preparation made of chewed bread mixed with the “fasting spittle” to find sure relief.

The central thesis of the treatise is that great salutary effects may be derived from saliva obtained in the morning, during fasting. Since the benefit can be shown to be great if it is applied to external parts of the body, we should expect comparable efficacy when it is conveyed to the entrails. Indeed, the author avers that the fasting saliva is improved in its nature, properties, and actions once it is mixed with the bile and the pancreatic, gastric, and intestinal juices. The saliva’s role is not only to soften food; we are all aware that eating would be difficult and uncomfortable in the absence of salivary lubrication. But mixed with digestive secretions, saliva serves crucial ends in the organism. It “dissolves all manner of viscous humors and fabulous concretions” that obstruct the mouths of the lacteals, impeding the passage of the chyle, and in this manner facilitates the disposal of “all corrupt humors to discharge by stool, urine, and insensible perspiration.”

Thus, the author advises sufferers from diverse ailments to take a piece of bread crust while fasting in the morning. Fasting confers optimal curative strength (the prescription of abstinence, we suspect, introduces a note of mystical self-mortification agreeable to the idea of healing). The reasons adduced to justify the choice of bread crust as the preferred agent to convey the “fasting spittle” down the alimentary tract need not distract us here. Not that bread has any health-restoring powers: It acts merely as conveyor of saliva. The important point is that saliva, mixed with secretions of the digestive system, becomes “one of the greatest dissolvent medicines in nature; and at the same time one of the safest that ever was communicated to mankind; a remedy that, if steadily pursued, will cure both the gout, the gravel, the stone, the asthma, and dropsy.”

Today’s medical scientists, it must be owned, do not share this kind of salivary enthusiasm. Still, the observation that all animals instinctively lick their wounds, and that wounds in the oral mucosa (for instance, after a tooth extraction) heal much faster than those of skin or other sites, led researchers to suspect the presence of a healing principle in saliva. Indeed, a number of beneficial substances were already known to exist there, such as antibacterial and antifungal compounds, and factors that promote blood clotting, but those that speed up the healing of wounds remained elusive for a long time. It is of no small interest that researchers have of late identified some, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), histatins, and leptin.

Beware: Amorous effusions from man’s best friend may pass on to you exotic infections worse than any you could get from a similarly demonstrative fellow human being.

Although lacking the fervor of Albert the Great, or the hyperbolic enthusiasm of the 19th-century advocate of the matutinal “fasting spittle,” present-day investigators have been sufficiently impressed by the bactericidal effects of saliva to wonder whether being licked by pet dogs might be, after all, a clean and salutary practice. Not so, they concluded after due investigation: The bacterial flora in the saliva of animals is radically different from that of humans. Therefore, beware: Amorous effusions from man’s best friend may pass on to you exotic infections worse than any you could get from a similarly demonstrative fellow human being.

Fortunately, the human salivary defense mechanisms identified are so numerous that they now outnumber the digestive factors. Saliva contains immunoglobulins; lysozyme (actually a family of so-named powerful enzymes which damage the cell walls of bacteria); mucins that protect the oral mucosa and cause selective adhesion of potentially harmful bacteria and fungi; plus a growing array of antibacterial peptides; all these are constituents of an impressive and effective barrier to infectious agents in saliva.

There is little doubt that important, new therapeutic agents will be found in saliva. At the present time, however, the main interest of biomedical experts focuses on its diagnostic potential. This fluid is increasingly recognized as a “mirror” or a “window of the state of the body,” whose analysis promises to become more informative than that of urine or even blood samples in many conditions.

For one thing, compounds of medical interest travel in the blood usually bound to protein or modified in various ways, whereas their detection in saliva reflects more precisely the biologically active molecules. Moreover, saliva samples are obtained noninvasively and painlessly, which is no small advantage to patients. Thus far, one problem has been that molecules at the cellular level exist in minute amounts, of the order of pico- and nanograms. The extraordinary advances in nanotechnology and the exquisitely sensitive amplification techniques used in molecular biology will certainly favor the use of saliva in diagnostic testing. The biomedical analysis of saliva may become an extraordinary, unprecedented advance in the accurate diagnosis of a great variety of diseases.

In striking contrast to the wonders that the ancients fancied in the salivary fluid, and the high esteem with which medical science presently views it, the general public’s recent attitude in the West has been one of neglect, if not outright disdain. Saliva is joined to ideas of offense, vulgarity, or impudence. Spitting in somebody’s face is universally considered a serious affront, an expression of hatred and disdain. Spitting on the floor in public is generally viewed as ill-mannered, although it was not always so. The fact that saliva is being constantly produced must have engendered in some people the feeling that they needed to rid themselves of some of it by ejecting it forcefully, wherever they chanced to be.

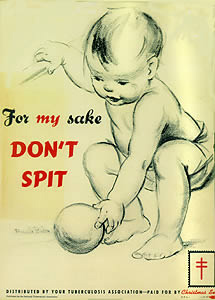

placard of the American Lung Association, 1943

This perception was so prevalent that the spittoon, or receptacle for spittle, also known as “cuspidor” (from the Portuguese cuspir, to spit), became a very common presence. Those of us who grew up in the first half of the 20th century remember that spittoons were obligatory in bars and taverns, and frequently found in stores, banks, railway carriages, waiting halls, hotels, offices, and many other sites. In China, spittoons date from the time of the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907), and some were fine artistic objects in porcelain, decorated with traditional pictorial motifs on the outer surface. Although still produced, spittoons are now rare, and often present simply as decoration: They figure as part of the décor in the Senate Chamber of the United States. In the Supreme Court of this country, each Justice has a spittoon next to his or her seat in the courtroom, mostly out of respect for tradition. Since the spitting habit is largely lost, and the young are unacquainted with the traditional form and function of spittoons, these receptacles are likely to be used as wastebaskets.

The perceived urge to expel saliva manifested anywhere, regardless of the availability of spittoons. In consequence, the custom of spitting on the floor became widespread. Its frequency varied in different cultures; people in most Western countries did not think of it as impolite until the early 1900s. In China, the habit persisted longer among the older generation. The Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping kept a spittoon by his side even at important diplomatic meetings. A newspaper photograph shows him in conversation with the British Prime Minister in Beijing in 1984; a white spittoon is visible on the floor at his feet. As late as the second decade of the 21st century, China’s Vice Premier Wang Yang lamented the extended custom among Chinese citizens of spitting on the ground. Together with other tokens of ill-breeding, he felt this habit debased the worldwide image of China.

In the West, hygienic and biomedical considerations were the chief factors that put a stop to the habit of spitting on the floor. Tuberculosis was a scourge that devastated European populations throughout the 19th century and beginning of the 20th. Weighty scientific studies and international meetings of experts concluded that the abolition of floor-spitting, and of public spitting in general, by reducing the risk of spreading the airborne bacilli, would stave off the progress of tuberculosis. In the United States, the American Lung Association undertook a veritable “crusade” against spitting. Children in schools were given a list of 19 rules to observe, all of which hammered, in various tones, the injunction to avoid spitting: “1.—Do not spit. 2.—Do not let others spit. . . . 19.—Last, as well as first, DO NOT SPIT.” Brigades of boy scouts distributed notices and fixed posters with anti-spitting slogans. This campaign was still active in the 1940s.

In 1922, the French Senate approved a law that prohibited this unhygienic practice. The French, however, have long flaunted a collective propensity toward open rebellion against unpopular authority, which they call, not without pride, their tradition contestataire. The prohibition of spitting was implemented only after considerable resistance. Satire aiming at the anti-spitting signs and proclamations flourished. Theatrical comedies, popular songs, and humoristic publications liberally dispensed their mordant mockery targeting the very measures intended to enforce the prohibition. A popular ditty, appropriately named “Forbidden to Spit,” described the consternation of a passenger on a bus who feels the urge to spit on the floor, but the conductor stops him briskly, pointing at the sign recently affixed inside the bus. He then tries to direct the spittle at the window, only to be reprimanded harshly. Should he spit on the roof? On the conductor, perhaps? The man aims at various targets, only to be vigorously rebuffed each time as a filthy and ill-bred boor. At that moment, a vendor of French pastry goes by with a basket full of cakes on his head. He happens to be within range of the frustrated spitter, who, without giving it a second thought, ejects the saliva on the tasty vol-au-vents. The ditty ends here with this consoling thought: “At least it [i.e., the spittle] was not wasted!”

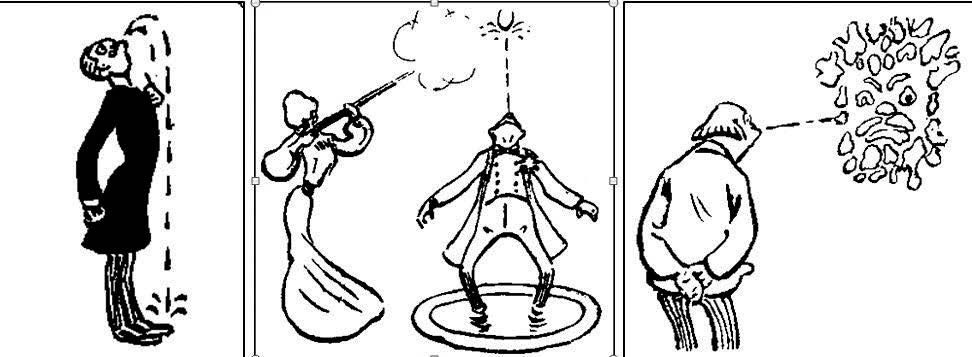

Early in the 20th century, a Parisian lampoon magazine farcically pretended that an American “professor of salivation” had introduced a course in spitting, whose aim it was to increase the dexterity of spitters. This was much needed, because governmental constraints and prohibitions forced the citizens to develop a better control on their ways of ejecting saliva. Several allusive caricatures illustrated the progressive degrees of spitting skill pursued by students.

from their own persons. Middle frame: Fourth lesson. Exercise to develop the

ability to spit at a distance. Right frame: Sixth lesson. For advanced students,

who try to sketch a portrait of Monsieur Camille Pelletan by means of spitting.

The sketch should be of such resemblance that a person fortuitously encountering

the sketch should be moved to exclaim: “For goodness’ sake! That is

Monsieur Pelletan!” From Le Rire (Paris), no. 88 (October 8, 1904).

In sum, the collective attitude toward saliva may be characterized as one of ambivalence. Biomedical science has long pondered over the hidden curative principles that this secretion may contain, and in recent times uncovered a dazzling potential for its use in medical diagnosis. Contrary to the importance conferred on it in past centuries, popular opinion has more recently held it in a negative light, as a contemptible bodily product — admittedly useful in the early phases of food digestion, but otherwise fit to be thrown in a rival’s face. Its role in the transmission of contagious diseases — instanced dramatically by tuberculosis about a century ago, and in our times by viral respiratory infections of pandemic proportions — did not help to burnish the image of this fluid.

Frank Gonzalez-Crussi is Professor Emeritus in the Department of Pathology of Northwestern University Medical School. He is the author of several books, including “The Body Fantastic,” from which this article is excerpted.