The Air-Conditioned Cowboy: A History of El Rancho Vegas

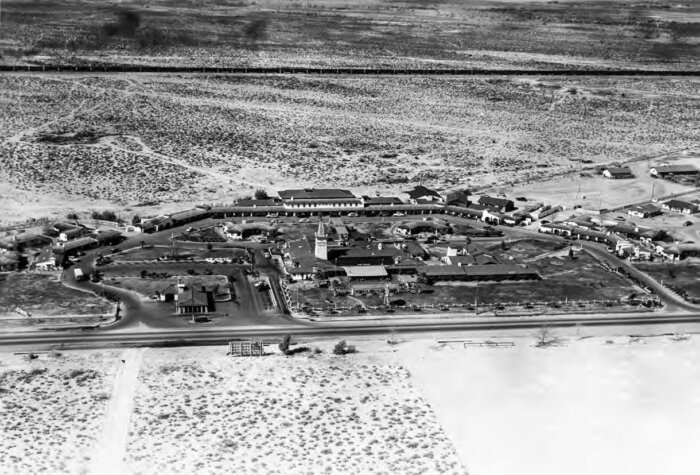

The Las Vegas Strip was born on April 3, 1941, when Thomas Hull, a California hotel operator, opened El Rancho. It was the first casino complex on Highway 91, the dusty little potholed road stretching through the Mojave Desert, connecting Los Angeles to Las Vegas. Locals were beyond surprise. Two observers wrote later, “Two miles out! Middle of a desert! To promoters and builders in Vegas proper, the idea was insane.”

Even the lady who sold Hull the land was astonished. Legend has it that she offered it for free, since she thought it was “worthless.” Nevertheless, Hull wrote a $57,000 check for 57 acres. A bargain, he thought, much cheaper than downtown, and outside city taxation limits.

Would this be another of Hull’s failed business ventures? In 1913, he had first tried his luck with mining in Mexico, but in the midst of the Mexican Revolution he ran into Pancho Villa’s army and had to walk 600 miles to get back to the border. He operated a movie theater, then a state-of-the-art industry, but it flopped.

Hull finally hit the jackpot in the hotel business. He had traded on his flying past when marketing San Francisco’s Bellevue as a place for aviation heroes. Its success helped him to develop a luxury version of the motel, a new invention that rendered obsolete auto camps, which provided small cabins and public toilets to drivers. In 1925, the first “Mo-Tel,” a portmanteau of “motor” and “hotel,” gave drivers more hotel-like privacy and facilities all under a single roof, including a grocery market, a restaurant, and a private bathroom in each room. Hull called his version the “El Rancho,” built a few in California, and planned to build one in Las Vegas.

Hull read in a highway engineering survey that almost one million cars traveled on the Los Angeles highway between Nevada and Southern California every year. Since his motels relied on passing automobilists, not downtown pedestrians, the highway location was perfect, despite being in the middle of the desert. In fact, Hull had had his eyes on Las Vegas ever since he had explored it three years earlier as a resort destination with his architect, Wayne McAllister. He was commissioned to design “the Caliente of Nevada,” a smaller version of Tijuana’s Agua Caliente, the spectacular casino-resort that Mexico’s President Cárdenas had turned into a state-run school after outlawing gambling. But investors refused to take the risk. Now backed by a private loan from Texas, Hull resuscitated the idea.

“Dress is informal. Bring your westerns.”

But Hull, who was not a gambler, initially planned to build a motel only, just like the other El Ranchos, without a casino. During construction, his local friends said: “Why don’t you build a casino building?” The adding of the casino to the resort was an afterthought, merely a geographic add-on to a motel that happened to be built in Las Vegas.

McAllister also deviated from the El Rancho template elsewhere. While it was a luxury motel, it could not be perceived as too fancy, which would have turned off local patronage, accustomed to Western-themed places. An observer wrote of Las Vegas: “The mood is … ‘Western,’ lower middle class, proletarian even … people are … quite without pretension … their shirts open at the throat. … Old clothes and battered hats are common.”

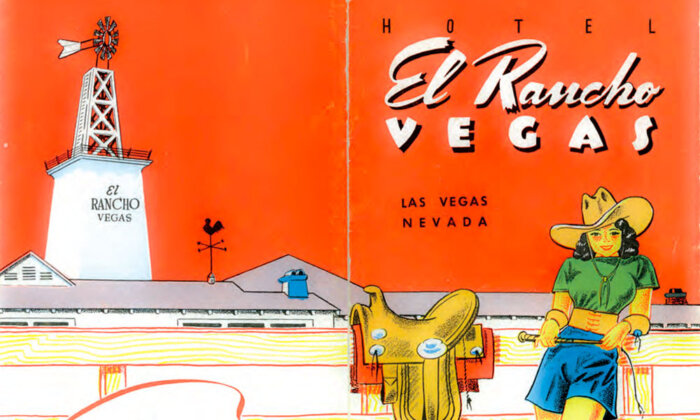

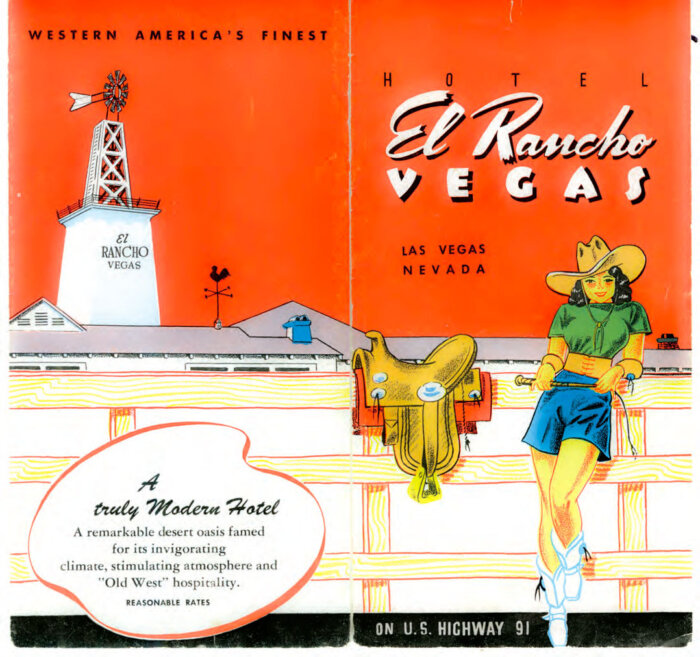

Therefore, McAllister designed the interior in the local “Western” style. He hung wagon wheel chandeliers from the ceilings. He draped cowhide curtains from poles with cattle horns. In the lobby, he built a two-story stone chimney, a fake fireplace, mounting deer heads. “El Rancho Vegas is the physical expression of the warm hospitality that has been the tradition of our great Southwest since the days of the covered wagon,” the publicity brochure stated. “Dress is informal. Bring your westerns.”

But the Western theme also led to some glaring contradictions. The nostalgic décor clashed with the ultramodern facilities of what was billed as “a truly modern hotel.” McAllister built an “Old West” with a swimming pool, right next to the highway. Downtown casinos did not have the space for such facilities. It beckoned passing automobilists eager for a swim after a long, dusty, desert ride. “Instead of hiding its glittering swimming pool in some patio,” noted the Saturday Evening Post, “they stuck it in their show window, smack on Route 91. It was a stroke of showmanship. No traveler can miss the pool, few can resist it.”

And the cowboys were quite the landscapers. Hull hired a staff of ten gardeners to maintain the lawn, fenced off by rough-hewn logs with crosshatch patterns typical of the Old West. He imported full-grown trees and rock waterfalls, soaking up to 10 million gallons of water per month from Las Vegas’s groundwater wells — hardly a sign of frontier scarcity.

The Old West resort was also air-conditioned. Even the windmill, a key design element of the El Rancho chain since automobilists could see it from afar, did not actually pump water but held the air-conditioning equipment. And to make sure it could be seen at night, McAllister lined the blades with neon. “Stop at the Sign of the Windmill” became the motel’s slogan. But Hull did not rely solely on his windmill to attract drivers; he convinced the local radio operator to move his station and tower to the resort, with the proviso that the station must mention that it aired “from the fabulous grounds of the fabulous El Rancho Vegas,” every 20 minutes.

The El Rancho, with its neon windmill looming over a mix of ranch and Spanish mission-style buildings, air-conditioned cowboy interior and radio tower included, was a giant paradox. But unlike other architects, McAllister was not hung up on achieving an integrated identity. A high-school dropout, he once bid for the design of the Agua Caliente. His plans called for an overall Spanish colonial revival-style building, adding baroque touches and Moorish elements, a Louis XIV room, and a Zigzag Moderne dining room. He tiled a 150-foot-tall power plant smokestack, encrusting it with ironwork, and turned it into a minaret. His client loved it.

Not bogged down by an architectural education that emphasized “honesty” of function and Zeitgeist, McAllister held a philosophy closer to the original Californian architects, the padres who built the Golden State’s missions in the 18th century. They borrowed haphazardly from their memories and impressions of Europe, mixing Roman domes and arches with Spanish bell towers. While it was rife with contradictions, and surrounded by little but dry desert, the eclectic mix of El Rancho was nevertheless a huge success. “The place was jam-packed from opening night on,” Garwood Van, the El Rancho bandleader, said. “Why? Highway 91 was so busted up that if you went over 40 miles per hour, you’d break an axle.”

McAllister had added just enough of the Old West. Even Hull got into the spirit, surprising tuxedo-wearing casino patrons on opening night by showing up in cowboy boots and a ten-gallon hat, drawling “Howdy Pardner.” He also forced his staff to wear hand-embroidered Western outfits. “We wore guns; we were all cowboys,” Guy Landis, the bass player, later said. Only the El Rancho Starlets, showgirls from Hollywood, relied on fewer clothes; one observer remembered them as “very pretty, with scantily-clad outfits and good figures.” Under the umbrella of the Western theme, the El Rancho somehow just managed to be the most novel, comfortable, and risqué of all.

Ironically, a man who had never gambled before had unintentionally built the Strip’s first casino complex

The Western theme helped render this lavish and modern hotel less intimidating. The Saturday Evening Post observed: “The [El] Rancho somehow has managed to make the riveter, the carpenter and the truck driver at home in overalls in the same rooms with men and women in smart clothes, with an eloping Lana Turner posing for news photographs. … No resort is likely to succeed in Vegas that doesn’t accomplish this democracy.” It would thus set the tone for the future Strip.

The El Rancho immediately enhanced the importance of that dusty, potholed road stretching through the barren Mojave Desert. Other hotel and casino developers would take a serious look at what Hull had built.

Even though the casino was an afterthought, Hull had invented the perfect casino complex. The large lot enabled him to include a whole range of facilities downtown casinos could only dream of, including a swimming pool, parking lots, a dining room, a coffee shop, a travel agency, badminton courts, and even riding stables with 15 horses. With a range of resort facilities at their convenience, guests would never need to leave the premises. By including a hotel, Hull’s casino had a captive audience.

Ironically, a man who had never gambled before had unintentionally built the Strip’s first casino complex, and set the model for future developments: a self-contained and luxurious resort along a highway — where no one worried about using the right fork.

Stefan Al is a Dutch architect, urban designer, educator and TED Resident, based in New York City. He is the author of several books, including “The Strip: Las Vegas and the Architecture of the American Dream,” from which this article is excerpted.