The 20th-Century Obelisk, From Imperialist Icon to Phallic Symbol

Previous centuries did not miss the fact that obelisks make a visual rhyme with a certain male body part. In the 1520s, for example, the brilliant poet and pornographer Pietro Aretino was quite specific about the association, using the same word, guglia, for both. Even the sex-obsessed and sex-denying 19th century made the connection with greater frequency than those looking for evidence of Victorian prudery might expect.

There is a faint but persistent undercurrent in 19th-century scholarship about the relationship between obelisks and the phallus, though that connection was usually relegated safely to the far distant past. Hargraves Jennings, who hinted at such associations in his pamphlet, “The Obelisk,” was also the author of a series of privately printed books documenting similar ancient monuments throughout the world, part of his attempt to recover the legacy of what he saw as a worldwide prehistoric phallic religion. But in this context the obelisk was a phallus, not a penis. Occasionally, the association could become a bit more explicit, as when the poet Algernon Charles Swinburne noted that: “Her majesty has set up — I should say erected — a phallic emblem in stone; a genuine Priapic erection like a small obelisk.” But in the 19th century such pointed talk was reserved for letters and pub chat. That the obelisk had represented a phallus in antiquity was an intellectually acceptable, if not entirely respectable, idea; that an obelisk might still be one today was a concept best reserved for private moments.

It was Sigmund Freud who let the cat out of the bag. Although Freud did not include obelisks in the extensive and imaginative catalog of phallic symbols — “things that are long and up-standing” — that occupies many pages of both his “Interpretation of Dreams” and “Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis,” he might as well have. For he did include tree trunks, along with knives, umbrellas, water-taps, fountains, extensible pencils, and zeppelins. In a rare moment of interpretive unanimity, Carl Friedrich Jung concurred, specifically noting the obelisk’s “phallic nature” in his “Psychology of the Unconscious.” The two great men had spoken, and from then on nearly everyone who cared to make the connection seems to have done so. In 1933 Nathanael West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, sitting in a park, hungover and quite possibly suffering a concussion, became alarmed at an obelisk whose shadow “lengthened in rapid jerks, not as shadows usually lengthen,” and which “seemed red and swollen in the dying sun, as though it were about to spout a load of granite seed.” A penis, not a phallus. In a more popular context, in the 1956 Biblical epic, “The Ten Commandments,” Cecil B. DeMille made the erection of a great obelisk the centerpiece of an early scene that established the testosterone-fueled rivalry between Yul Brynner’s strutting Ramesses II and Charlton Heston’s chest-heaving Moses.

Today it is not Egyptian pharaohs, Roman emperors, or Renaissance popes who leap to mind when people stumble across an obelisk; it is Freud.

Scholars were less vivid in their language, but in 1948 the establishment Egyptologist Henri Frankfort declared — still, it’s true, in the discreet context of an endnote — that “it is likely that the obelisk did not serve merely as an impressive support for the stylized bnbn stone which formed its tip, but that it was originally a phallic symbol at Heliopolis, the ‘pillar city.’” By mid-century, what was once a whispered, almost occult association had become practically banal. In 1950 the psychiatrist Sándor Lorand could include a young boy’s dream about New York’s Cleopatra’s Needle in his analysis of the early stages of fetishistic obsession without even feeling the need to spell out exactly what role the obelisk might play.

Today it is not Egyptian pharaohs, Roman emperors, or Renaissance popes who leap to mind when people stumble across an obelisk; it is Freud. The subtext has become the text itself. Russell Means, the Lakota/Oglala activist who led the 1973 takeover at Wounded Knee, was making a political point when he described the obelisk to Custer at Little Big Horn as “the white man’s phallic symbol.” But the designers who placed the Washington Monument (pointy side down) between a spread pair of disembodied legs on the cover of a mainstream, trade paperback about the seamy underside of Washington, D.C., likely had no political agenda. They were just trying to sell books. The novel, naturally, was called “The Woody.”

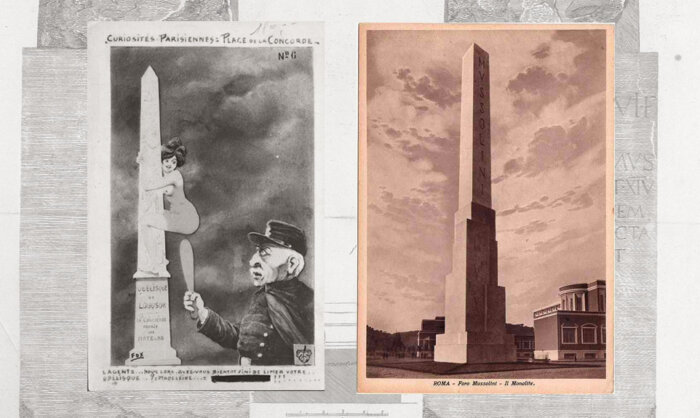

In historical terms this change has been blindingly swift. Obelisks retained their original meaning for thousands of years. Yet it is only a matter of decades between the slightly naughty French postcard of the early 1900s that features a policeman inquiring of a young woman, who clings to the monument in the Place de la Concorde, whether she has finished “polishing the obelisk,” to the moment on December 1, 1993, when the clothing manufacturer Benetton and the Paris chapter of ActUp marked World AIDS Day by putting a 22-meter pink condom on the very same obelisk. That, apparently, made the implicit a bit too explicit; the condom had not been approved by the Ministry of Culture and was gone within hours. Time, however, moves ever more quickly, and a vivid image cannot be kept down; in 2005 Buenos Aires decorated its own gigantic obelisk-shaped monument in a similar manner — this time with the full support of all relevant governmental bodies.

But sex is not the only association obelisks carried through the 20th century. They have become increasingly caught up in the mystical stew of theosophy, pagan revival, and the occult that has come together in the New Age movements of the last few decades. This has proven fertile ground for the revival of the more outrageous and conspiratorial Victorian writers on obelisks and ancient Egypt. Their books are now, paradoxically, much easier to find and buy than major works of 19th–century Egyptology. There is, to this day, no English translation of Champollion’s “Précis du systême hiéroglyphique,” his summa on Egyptian writing, or even of his short letter to Joseph Dacier, the key document explaining his ideas about hieroglyphs; but works by marginal figures like Hargraves Jennings and John Weisse, who found evidence of ancient Freemasons wandering the upper Midwest, have been reprinted and are readily available. Around the world, New Age shops and websites nearly all sport obelisks among the crystals, pyramids, and other mystical gewgaws available to channel good energy or dilute and disperse bad. The obelisks are usually advertised as effective at dispelling negative forces, such as “trapped energy, which could cause destruction like volcanoes.”

Around the world, New Age shops and websites nearly all sport obelisks among the crystals, pyramids, and other mystical gewgaws available to channel good energy or dilute and disperse bad.

Hollywood saw this mystical resurgence early and wove it into the science-fiction movies and television shows that proliferated in the 1960s. The mysterious resonating monolith that drives the plot of “2001: A Space Odyssey” is not, technically, an obelisk, but plays perfectly the otherworldly role ascribed to Egyptian obelisks in the farther reaches of the New Age. “2001” was one of the sensations of the spring of 1968; later that year the creators of the television series “Star Trek” were much more explicit, when, in shameless emulation, they included an obelisk in “The Paradise Syndrome.” That episode features a wise and peace-loving group of American Indians who, at some point in the distant past, had been transported to a faraway planet. There they live in safety, protected by strange forces that emanate from an obelisk that sits on a small altar in the woods. Unlike the “2001” monolith, this one actually looks like a short, fat obelisk and even sports hieroglyph-like inscriptions.

This manifold expansion of meaning and association is characteristic of the whole 20th century. The very explosion of monument building in the late 19th and early 20th centuries probably helped accelerate this process. Obelisks and obelisk-like monuments sprouted up everywhere in the decades on either side of 1900. Many, to be sure, were dedicated to victory and commemoration, but the sheer number — nearly every city in Europe and the Americas has a brace of them — meant that obelisks were applied to ever-stranger purposes. In 1896, at Pennsylvania State University, Magnus C. Ihlseng, a geology professor, found himself so pestered with questions about the qualities of the stones found in Pennsylvania that he organized the construction of a 33-foot obelisk, made up of all “the representative building stones of the Commonwealth, and thus to furnish in a substantial form an attractive compendium of information for quarrymen, architects, students, and visitors.” The stones are organized to reflect the geology of the region, with the oldest ones near the base.

Obelisks took on similarly untraditional forms throughout the century. The 1922 competition to design a new headquarters for the Chicago Tribune drew two different proposals for obelisk-shaped towers, including one from Chicago architect Paul Gerhardt, who also submitted a proposal for a building shaped like a gigantic papyrus column. Neither won. Although the idea of an obelisk as haven for office workers seems a long way indeed from Egyptian solar cults, such a building would have been very appropriate to the well-nigh pharaonic ego of the Tribune’s publisher, Robert McCormick. Obelisks appeared on every scale and in every imaginable context. Smaller sorts of executives could obtain smaller sorts of obelisks. In the 1960s, for example, the Injection Molders Supply Company offered 20-inch plastic desk obelisks for the “plastics executive who has nearly everything.”

The sign for the Luxor Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas, one of a series of thematic fantasylands along the Strip — New York! Venice! Egypt! — is a giant obelisk, complete with accurate hieroglyphs that celebrate the immortal kingship of Ramesses II. The obelisk lures people to the pyramid-shaped hotel, whose check-in desk can be reached via a drive-through sphinx. Inside, guests can find (in addition to floor shows and slot machines) a remarkably accurate reconstruction of King Tut’s tomb as well as a New Age-inflected movie experience about the mysteries of the pyramids.

Even as new obelisk-shaped monuments sprouted up, the meaning of existing ones shifted. The Bunker Hill Monument is a case in point. It was constructed in the 1820s and 30s as a memorial to a Revolutionary War battle and to the very idea of liberty. So it remained, but by the end of the 19th century it had become an even more powerful symbol of place — of Charlestown, Massachusetts. It became the emblem of the city (and after annexation by Boston, the neighborhood), appearing on shop signs, the bottles of the local pickle packager, and the jackets of high-school students. By the 1990s the identification of neighborhood and structure was so complete that when a dramatic new cable-stayed bridge was built across the Charles River from Boston’s North End to Charlestown, the designer, Swiss engineer Christian Menn, fashioned the bridge’s towers in the shape of obelisks. His reference point was the monument itself, a symbol of place, rather than the ideas the monument was originally intended to embody. The bridge’s towers and the monument now form a trio of obelisks across the Charlestown skyline, reinforcing the association yet further.

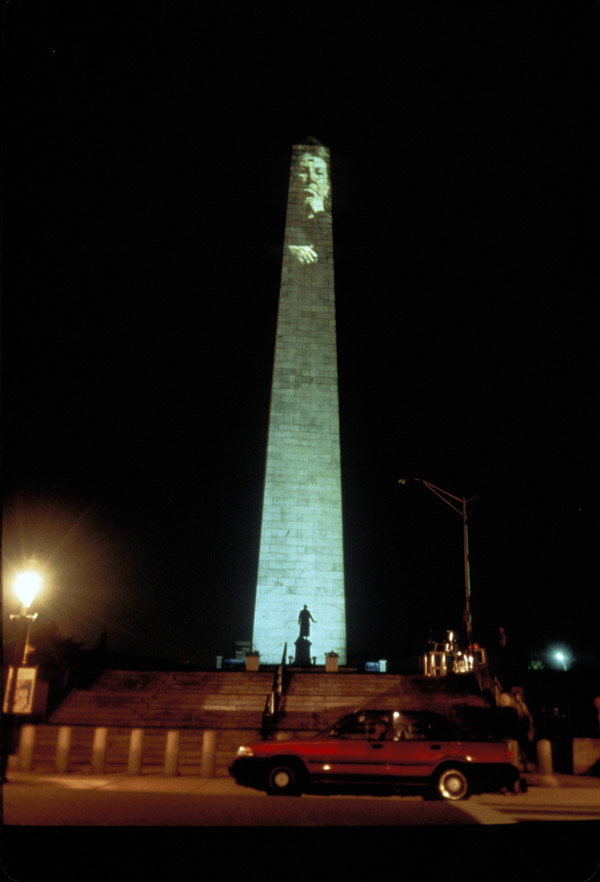

But symbolism can also come full circle. In 1998 Boston’s Institute of Contemporary Art commissioned a major piece by the artist Krzysztof Wodiczko, who has specialized in gigantic projections, generally on the sides of buildings. In Boston he chose the Bunker Hill Monument as his canvas. During the 1970s and 80s, Charlestown, then a tight-knit and somewhat insular neighborhood, had been the scene of violent gang warfare, accompanied by a rash of murders. These became known as the “code of silence” killings, as the police consistently found that eyewitnesses were unwilling to speak about the crimes. By the late 1990s the neighborhood had changed, tensions had calmed, and Wodiczko convinced people to talk about the murders for his projection. For six nights, the monument itself seemed to speak with the voices of many of the victims’ mothers, who told of the murders and the murdered — of freedom, loss, and sorrow. It was a plea for peace and liberty, but on a much more personal and visceral level than the monument’s designers probably envisioned.

Other 20th-century artists found inspiration in the obelisk’s form itself. Barnett Newman’s great, enigmatic Broken Obelisk — a huge sculpture of COR-TEN steel consisting of a pyramid whose apex is just barely kissed by the point of a broken, upturned obelisk — may be the most inscrutable and moving “obelisk” of the century. The whole rises nearly 39 feet (nine meters) before the broken shaft of the steel obelisk trails off into the air. The sculpture not only embodies the very form of an obelisk, but even maintains the curious balance of great size and delicacy that characterizes the Egyptian original. The effect is reinforced by the fact that the contact point between the massive pyramid and the only slightly less massive obelisk is but a few square centimeters. Although Newman claimed some inspiration from his own childhood memories of the Central Park obelisk, he was unwilling to assign the piece specific meaning. Always a bit gnomic about his work, Newman wrote to John de Menil, who acquired one of the three versions of the sculpture, only that: “it is concerned with life and I hope I have transformed its tragic content into a glimpse of the sublime.” Perhaps in response, de Menil installed the sculpture as a monument to Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Any number of 20th-century states, cities, and rulers tried to turn obelisks to their own political or commemorative advantage. Nearly all seem to have suffered from cases of equivocal symbolism.

Yet amid this very modern cacophony of meanings, the traditional association of obelisks with political power has never been drowned out completely. Any number of 20th-century states, cities, and rulers tried to turn obelisks to their own political or commemorative advantage. Nearly all seem to have suffered from cases of equivocal symbolism. In the early 1920s, the government of the newly born Czechoslovak state hired the Slovenian architect Jože Plečnik to oversee the Prague Castle, which was being transformed into the seat of the new government. One of Plečnik’s ideas was to raise a gigantic obelisk — a true monolith — as a combined celebration of the new state and memorial to those who had perished in World War I. The obelisk, which would have been one of the largest ever erected, fell down an embankment during transit from the quarry in southern Czechoslovakia and broke in two — an event that in recent years has been taken as an ominous prefiguring of the eventual severing of the state itself. The salvageable half, still a very respectable 17 meters, stands by St. Vitus’s cathedral in the inner court of the castle. Fifteen years later, in 1936, the city of Buenos Aires also built a huge obelisk — this one of concrete and steel — in commemoration both of the city’s 400th anniversary and its arrival, in the early 20th century, as one of the world’s great cities. The obelisk became a symbol of the city, but it, too, took on a more sinister cast after Argentina began its long slide into political darkness. One morning in 1974, in what was advertised as an attempt to calm the city’s notorious traffic, Porteños awoke to find the obelisk bearing a great lighted sign that read “Silencio es salud” — “Silence is Health.” In the age of Argentina’s right-wing dictatorship, it didn’t take much to realize that the banner referred not only to car horns.

Trujillo’s government fell in 1961, and, in a pointedly anti-phallic gesture, his obelisk now bears a mural by Elsa Núñez and Amaya Salazar that celebrates the Mirabal sisters, three women who effectively martyred themselves in 1960 to help end the dictatorship.

In Latin America obelisks even made the Marxian turn from tragedy to farce. Also in 1936, Rafael Trujillo, dictator of the Dominican Republic, ordered up a gigantic obelisk for Santo Domingo, part of his grand project to modernize and remake the city, which was, of course, renamed Ciudad Trujillo. The traditional imperial symbolism was given a nicely 20th- century sexual overtone in the dedication ceremonies, during which Jacinto Peynado, Head of the Pro-Erection Committee, praised the monument as mirroring Trujillo’s own “superior natural gifts.” At the same time, in a blatant sop to the dictator’s American sponsors, the seaside road in which the obelisk stands, the Malecón, was renamed Avenida George Washing- ton. Trujillo’s government fell in 1961, and, in a pointedly anti-phallic gesture, the obelisk now bears a mural by Elsa Núñez and Amaya Salazar that celebrates the Mirabal sisters, three women who effectively martyred themselves in 1960 to help end the dictatorship. The murals were unveiled in 1997, on International Women’s Day.

The 20th-century political leader who adopted the obelisk with the most historically informed style was Benito Mussolini. In 1932 the Italian dictator had an Art Deco–inflected “obelisk” raised on the banks of the Tiber, north of Rome’s old city center. The huge monolith bears no hieroglyphs, just the words “Mussolini Dux” in great blocky letters that run down the monument’s side. The largest piece of Carrara marble ever quarried, the obelisk was the centerpiece of the Foro Mussolini (now the Foro Italico), a grand complex of sports stadia and arenas intended as part of the Fascist campaign to encourage physical fitness — itself part of Mussolini’s plan to restore Italy’s imperial power.

It was a tall order. Italy, seat of the original European empire, came very late to the new imperialism of the 19th and 20th centuries. There had been no country of Italy at all until the 1870s, when Giuseppe Garibaldi united a fractious group of principalities into an equally fractious kingdom. The new country almost immediately began trying to acquire overseas colonies. Italy turned first to Africa, but by the end of the 19th century other European powers had neatly parceled out almost the whole continent. Only Liberia (effectively a protectorate of the United States) and Africa’s northeast corner were not yet part of the colonial system. So Italy focused its attention on the “Horn” of Africa. In short order it acquired both Eritrea and what is now the southern part of Somalia. The Italians tried to conquer Ethiopia as well, but met with an embarrassing defeat in 1896. There matters remained until Mussolini came to power in the 1920s. He renewed Italy’s push for empire, and in 1935 managed to defeat Ethiopia.

Mussolini got lucky. Among the benefits of invading Ethiopia was that, like Egypt, it was the seat of an ancient culture, one that had itself been a powerful imperial force. The kingdom of Aksum flourished from the first to the eighth centuries CE, growing rich from control of long-distance trade from the interior of Africa to the Mediterranean and Indian Oceans. Some of that wealth was spent on monuments. In the fourth century CE, the kings of Aksum had erected a series of enormous stone stelae at their capital. The great standing stones are not obelisks exactly, but they were close enough for Mussolini’s purposes. In 1937 he ordered one brought to Rome. He originally planned to set it up in the E.U.R., a model city of Fascist planning to the west of Rome’s center. Now a tourist attraction in its own right, the neighborhood, like a painting by Giorgio de Chirico come to life, captures better than any other place the aesthetic fantasies that inspired Europe’s fascists. Supremely orderly, it is ancient-seeming yet newly made at the same time — a calm, predictable place in a famously noisy, busy, and very unpredictable city. In the end, though, it was decided that the Aksum obelisk was better suited to the city of Rome proper, and Mussolini had it set up in the Piazza di Porta Capena, near the Circus Maximus, in front of the Ministry of the Colonies. E.U.R. received a gigantic “obelisk” dedicated to Guglielmo Marconi instead.

Twenty-four meters (78 feet) high and weighing 160 tons, the monument from Aksum was very much worthy of comparison to the ancient emperors’ obelisks. It is made of nepheline syenite, a hard rock similar to granite that was probably quarried about seven miles west of Aksum, at Wuchate Golo. The monument was one of many erected as part of a tomb complex in the ancient city; more than 200 survive. The largest of these originally stood 33 meters high (nearly 100 feet) and weighed about 550 metric tons, making it probably the largest monolith ever erected. At ground level its surface is carved with a false door; tiers of false “windows” climb to the top, as in a multi-storied building, perhaps representing royal residences in the next world. These stelae seem to have functioned as giant markers for subterranean tombs, probably those of the Aksumite rulers who governed just before the royal line forsook its polytheistic religion to adopt Christianity. The Aksum kingdom faded by the eighth century, and, like Rome’s obelisks, many of the stelae fell in subsequent centuries. Among the fallen was Mussolini’s, which was toppled in the 16th century, during a Muslim rebellion in Christian Aksum. It broke in three pieces, making it easier to transport when the Italians carried it overland to the coast.

The obelisk stood in Rome for only 10 years before Mussolini’s fall brought a new government and an admission that the obelisk should never have been taken. In 1947 the new Italian government agreed to return all loot taken from Ethiopia during the occupation. But they didn’t send the obelisk back. In 1956 the Italians again signed a treaty with Ethiopia, agreeing that the obelisk “was subject to restitution,” though leaving it ambiguous who was to pay the bill to send the stele home. Again, nothing happened. In 1970 the Ethiopian parliament threatened to cut off diplomatic relations with Italy unless the obelisk was returned. Again, nothing. The matter faded somewhat after the overthrow of Emperor Haile Selassie in 1974 brought a long period of political chaos, but the campaign was renewed in the 1990s by a group of Ethiopian and Western intellectuals. When the Italian government finally committed itself to returning the monument, the project was delayed yet again by the 1998–2000 border war between Eritrea and Ethiopia. (Aksum is near the border.) But the case for return was strengthened in 2002 when a lightning strike damaged the obelisk, instantly demolishing the argument that it would be safer in Italy than in Ethiopia.

Even today, moving an obelisk is an engineering challenge. First the stele had to be dismantled. A team of Italian and Ethiopian experts had assembled in 2000 to study the problem. Giorgio Croci, the engineer in charge, explained that the team was anxious to avoid creating cracks or doing any further damage, and planned to separate the pieces where they had been joined when the obelisk was erected in 1937. The engineers designed a scheme using computer-guided jacks, and, in 2003, finally disassembled the obelisk. The dismantling was accompanied by the cheers of a jubilant crowd of Ethiopians, and the monument taken to a warehouse near Rome’s airport, very close to the spot where Nero’s obelisk ship had been turned into a public monument two thousand years before.

Mussolini’s engineers had brought the obelisk to Rome by road and ship. This was no longer possible, as the roads in Ethiopia had disintegrated and the port used in the 1930s was now in Eritrea, a country that after years of war would never have permitted the Ethiopian monument to pass through its territory. Air transport was the only solution. The Italian company in charge, Lattanzi, described the obelisk as “the largest, heaviest object ever transported by air.” So big and heavy, in fact, that only two planes in the world were large enough to carry it: a Russian Antonov An-124 or an American Lockheed C5-A Galaxy. Both are themselves imperial objects, designed at the peak of the Cold War to ferry material to the far- flung proxy wars of the United States and the Soviet Union. The planes are so huge that the airstrip at Aksum had to be upgraded to handle the An-124 that took the monument home. Heaters were installed in the cargo bay to protect the stones from damage by freezing. Finally, nearly 70 years after the monument left Ethiopia, and almost 60 since the Italians first agreed to return it, on April 19, 2005, the first piece arrived back in Aksum. The other two pieces followed within the week. National celebrations commemorated the return, but there were critics as well. The move ultimately cost six million euros, and some Ethiopians questioned the amount of money spent on the project in a country without a stable and secure food supply. Others, mostly in southern Ethiopia, insisted that the cause célèbre was regional, rather than national — that it made little difference to them where the obelisk came to rest. Finally, in 2008, the obelisk rose again at Aksum — the very first wandering monolith ever to return home.

Amid all this imperial aspiration, wooly-minded New Age mythologizing, and pure unadulterated commerce, the real obelisks — their message no longer hidden behind a veil of allegory, but easily legible to any who can read hieroglyphs — still stand. Those obelisks are, more often than not, far from their original homes, but most are now equally at home in their new locations. They are majestic embodiments of the ancient culture that created them, but they are just as much the bearers of all the other ideas that have accreted to them over the many centuries since. Obelisks do not have a single meaning; they carry all the meanings ever applied to them.

Even so, the stones can speak for themselves. In Rome’s Piazza del Popolo, still a symbolic gateway to the city, stands the single obelisk conjured from the earth by order of Seti I in the 13th century BCE — more than three thousand years ago. It was completed by Ramesses II, who had it erected at Heliopolis, the city of the sun. It stood there for more than a thousand years, until in 10 BCE a new emperor — a conqueror — Augustus, wrenched it from its native place and carried across the sea to Rome. For five centuries it graced the Circus Maximus, until the new empire fell, and with it the obelisk. It broke and sank into the circus’s marshy ground. There it waited. Nearly a millennium later, it was excavated by order of an imperial pope and, in 1587, carried to its present site. The obelisk has stood there now for more than four centuries — four times longer than the Republic of Italy itself. Yet through all of the changes — geographical, intellectual, religious — the obelisk has remained the same. From time immemorial it has proclaimed, to all who could understand, the eternal fame of Pharaoh Ramesses II:

Horus-Falcon, Strong Bull, beloved of Maat;

Re whom the Gods fashioned, furnishing the Two Lands;

King of South and North Egypt,

Usimare Setepenre, Son of Re, Ramesses II,

Great of name in every land, by the magnitude of his victories;

King of South and North Egypt, Usimare Setepenre,

Son of Re, Ramesses II, given life like Re.

Perhaps not the sort Ramesses expected, and maybe a bit delayed, but immortality nonetheless.

Brian A. Curran was a renowned art historian and professor at Pennsylvania State University. Anthony Grafton is Henry Putnam University Professor of History at Princeton University. Pamela O. Long is an independent historian who has published widely in medieval and Renaissance history of science and technology. Benjamin Weiss is Director of Collections at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This article is excerpted from their book “Obelisk: A History.“