The 1950s Game That Glorified the Dangers of the Atomic Age

Uranium Rush appeared in 1955, as prospectors flocked westward in search of the newly sought-after resource. A decade earlier, when the United States first developed the atomic bomb using uranium from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then the Belgian Congo), combined with smaller amounts from Colorado and Canada, the element was falsely believed to be scarce. Now that the Soviets had produced their own nuclear weapons, the United States poured money into discovering uranium at home, declaring the Atomic Energy Commission the sole consumer and offering large bonuses to those who found the element on private or public land.

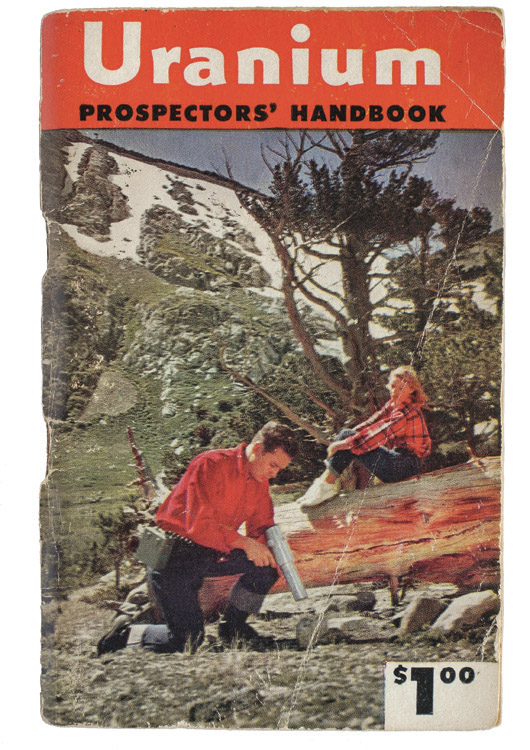

Just as families were encouraged to build fallout shelters as a contribution to the Cold War, so they were encouraged to spend a fun weekend hunting for uranium. Prospecting handbooks proliferated, and “uranium fever” served as the plot for B movies and television comedy episodes.

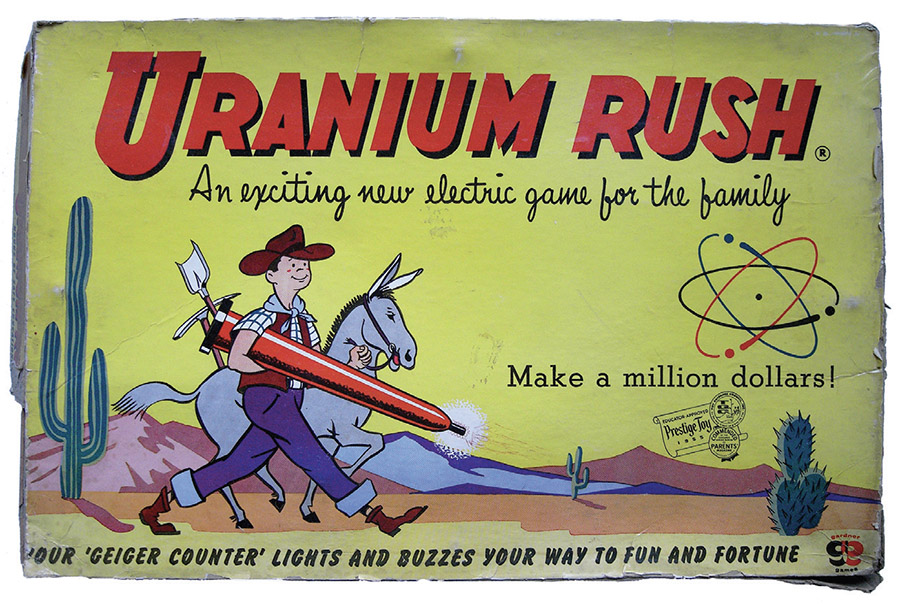

Uranium Rush capitalized on this hype, along with the general enthusiasm for atomic energy, the discovery of which was a source of national pride to many, despite the horrific destruction it had caused and continued to threaten. Americans sought to harness the mysterious whirling atom not only for weaponry and the development of nuclear power but also for jewelry, comic books, and dish detergent. It appears on the cover of the Uranium Rush box, along with a seal stating that the game is “educator approved” and an exhortation to “Make a Million Dollars!” Children could learn science and entrepreneurship all at once, aspiring to become either “uraniumaires” like famous prospector Charlie Steen or, failing that, nuclear physicists.

Intertwining fantasies of technological and geographic dominance are personified by the young white cowboy striding across the Uranium Rush box cover. With a giant, rocket-like Geiger counter casually tucked under his elbow, he sets off to claim the untapped power of the American West, a region perpetually portrayed as an unoccupied “frontier.”

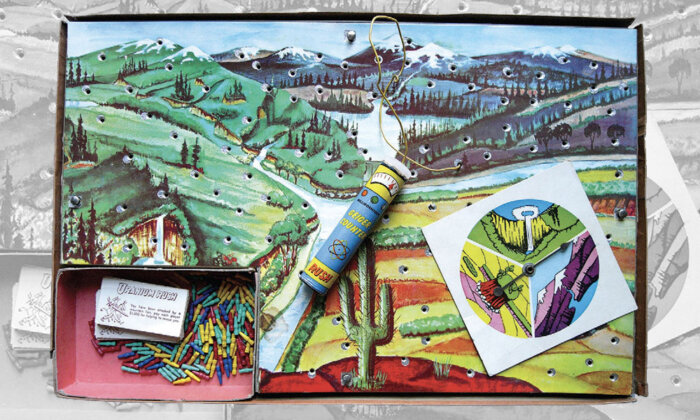

The game board inside presents a scenic landscape, presumably the Colorado Plateau, pocked with shallow holes that represent mines. After spinning an arrow to determine where to prospect, players pay the government to stake a claim, which can be traded before being tested for uranium. Each lucky strike pays $50,000, and the player with the most money when all claims have been staked wins. “Government instruction cards” detail various setbacks and strokes of luck familiar from the Western adventure genre, and from the wild accounts that famous prospectors such as Vernon Pick gave in popular magazines.1

Unlike some Geiger counters included in science kits from the era, the toy version in Uranium Rush does not detect radiation but instead features a light and buzzer that activate when a wire is touched to the correct mines. Wielding this oversize tool, players discover the landscape to be a circuit board, crackling with potential energy and exciting, though elusive, knowledge — the electric light itself having long been used to represent a new idea. Because the pattern of lucky strikes is determined by which of four metal posts the Geiger counter rests on, a player can memorize which claims to stake; the game board takes on the same disposable quality the U.S. government seemed to ascribe to western land itself.

Even for less attentive players, the initial thrill of this “exciting new electric game for the family” seems likely to have been short-lived. The game’s Geiger counter exemplifies the gimmick, a form described by the cultural theorist Sianne Ngai as intrinsic to capitalism: the quick fix that turns out to be neither. In Uranium Rush, the player reenacts the tedious work of finding resources to fuel the insatiable nation, using a device that promises to make the task easy and fun.

Claiming to educate, the gimmick instead obscures and mystifies. Ngai characterizes the gimmick as the site of multiple contradictions, mixing “dissatisfaction” and “fascination,” “overperforming and underperforming,” appearing “too expensive or too cheap,” “too new or too old.” 2 In the end, it is hard to know whether such gimmicks are more instructive of the logic of capitalism in their initial appeal or in their eventual failure to enchant.

Children could learn science and entrepreneurship all at once, aspiring to become either “uraniumaires” or, failing that, nuclear physicists.

The “quick fix” of uranium, with its odd mixture of futuristic technology and frontier mythology, is one that has failed the American West and its people again and again. The boom that inspired Uranium Rush turned to bust, as the Atomic Energy Commission, having procured an immense stockpile, withdrew its support, leaving behind economic and environmental ruin. Long aware of the dangers of radon gas exposure but reluctant to endanger the supply of uranium, the federal government disregarded reports by its own Public Health Service and placed the burden of regulation on ill-equipped individual states, resulting in death and illness for many who worked in underground mines.

To this day, hundreds of abandoned mines have not been properly cleaned up, and local people, in particular the Diné (Navajo) community, who were responsible for mining over half of the uranium obtained in this period, continue to suffer from uranium poisoning, increased lung illness, and cancer.3

As the writer Robert Johnson points out, secrecy has been an integral part of “the atomic mindset” since the Manhattan Project, and countless people all over the world, harmed by nuclear testing, medical experiments, or the processes of extraction and milling, only learned of their exposure to radioactivity years after the fact.4 While the uncanny optimism of games like Uranium Rush may thus seem unfathomable to us today, struggle over western land, its resources, and our understanding of nuclear power continues.

Emily Blair lives in Brooklyn, New York, working in design and web development. Her poetry has appeared in Gulf Coast, the Gettysburg Review, New Ohio Review, and the Brooklyn Poets Anthology, among others. This essay is excerpted from the volume “Playing Place.”

- Raye C. Ringholz, “Uranium Frenzy: Boom and Bust on the Colorado Plateau” (New York: W. W. Norton, 1989), 73.

- Sianne Ngai, “Theory of the Gimmick: Aesthetic Judgment and Capitalist Form” (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020), 1–3.

- Traci Brynne Voyles, “Wastelanding: Legacies of Uranium Mining in Navajo Country” (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), xii.

- Robert Johnson, “Romancing the Atom: Nuclear Infatuation from the Radium Girls to Fukushima” (Oxford: Praeger, 2012), 95.