Snail Stories for a Time of Extinctions

This article is republished from The Revelator under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Perhaps you’ve heard of George. He died on New Year’s Day in 2019. A so-called “endling,” George was believed to be the last known individual of his species — Achatinella apexfulva — a kind of Hawaiian tree snail.

His passing generated a buzz of media coverage, but the plight of the world’s endangered snails wasn’t long for the limelight.

Thom van Dooren wants to change that.

Van Dooren is a field philosopher and author, and his research and writing focus on the ethical, cultural and political issues around extinctions. While in Hawai‘i in 2013 writing about birds, the subjects of three of his previous three books, he met George and the small, but dedicated group of researchers working to protect Hawaiian snails.

He was hooked.

The Hawaiian islands, he learned, are home to staggering diversity of snails — with more than 750 species known to science. Sadly, though, at least two-thirds of those are already extinct, and some 50 more sit on the brink.

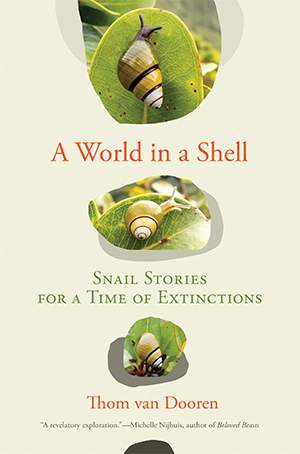

Van Dooren set out to learn why and what could be done to save the remaining populations. The result is the new book, “A World in a Shell: Snail Stories for a Time of Extinctions,” which tracks efforts to save the islands’ imperiled snails — including the work of the Snail Extinction Prevention Program.

The book provides insight into not just struggling gastropods in Hawai‘i but our global biodiversity crisis.

The Revelator spoke to van Dooren about why conservation efforts overlook invertebrates, what we can do about that, and whether Hawaiian snails stand a chance.

Why have things gotten so bad for snails in Hawai‘i?

The decline begins with the arrival of Polynesian people and the clearing of lowland areas for agriculture and the introduction of the Polynesian rat, which we now understand was not just about rats eating snails, but about rats eating seeds and transforming the forest environment in a way that didn’t work out particularly well for snails.

Those initial processes drastically scaled up with the arrival of European and American colonists.

Then, in the beginning of the 19th century with the arrival of Christian missionaries, we began to see a global trade of species, which is about sandalwood being logged in Hawai‘i and exported elsewhere. It’s about the arrival of more rats, European rats and others, that are also snail predators and also impact the forests.

And then it’s about the arrival of plantations of sugar, especially, and pineapple and ranching in the islands. All of these things cleared a lot of forests and drastically transformed what was left.

Then we have the shell collectors who arrived with the missionaries in the 1820s. Most likely, although we don’t have good records, they drove some species very close to, or even over the edge, of extinction.

And then came more predators with the arrival of the rosy wolfsnail, a carnivorous snail that tracks the native snails with their slime, and is, as one of the biologists put it, “vacuuming up the remaining species.”

And all the while, going on through all of this, is habitat loss caused by the military and tourism.

There’s so much going on condensed into these relatively small bits of land that have been sought after by so many people in different ways. And so much has been squeezed from them. The snails are really a casualty of that. I don’t think that’s a completely unique story. Many contemporary extinctions are about multiple interwoven causes, and they’re causes that cut across these kinds of ecological and cultural processes.

There are a lot of fascinating — and endangered — snails throughout the world. Why focus only on Hawai‘i?

I think there is a bit of a tendency to think about extinction as broadly an anthropogenic crisis, rather than looking at more specific details around particular extinctions. If we just tell global stories about extinction, we end up not really being able to say anything more than that humanity is the problem.

If we just tell global stories about extinction, we end up not really being able to say anything more than that humanity is the problem.

But by zooming in on Hawai‘i, I think that enables us to think about how extinction is tangled up with processes of colonization, militarization, globalization, et cetera. It’s not something that’s caused by humanity in the general sense. But it’s a much more concrete process of loss that’s tied in with particular histories, particular ways of ordering human life, particular ways of generating profit and of valuing and understanding the world.

And snails are also a victim of an invertebrate bias in conservation?

Yes, and it’s something that I have been guilty of myself in writing about birds for so long.

But 99 percent of the animal kingdom is invertebrates. Most of them haven’t even been described by science, and they’re disappearing rapidly. A lot of them are disappearing without ever even being described or named. But even the ones that have been, we often know very little about them.

If we’re lucky enough to know that they are endangered, we often don’t know enough about their life histories or about their needs to really understand what to do about it.

We talk about the biodiversity crisis as though we know what it is, as though we know who some of the main actors are — and they’re all big mammals and birds — but there really is this whole other unseen extinction crisis going on that’s really not very well understood, let alone spoken about.

How do we overcome that bias?

We need to approach the biodiversity crisis differently. It’s not just a case of developing a new category of charismatic microfauna and trying to add the odd snail or beetle onto that list of charismatic species. What we really learn from invertebrates is that there are just too many species and there are just too many of them at risk at the moment for us to continue to entertain a kind of one-by-one approach to conservation.

Of course, we’ve known that for a very long time, and there have been many other approaches to thinking about biodiversity loss on an ecosystem level, for example. We need to continue to do that. We need to continue to be thinking about habitat and about large-scale processes and about protecting whole groups of species together rather than one by one.

I also think there’s fundamentally a kind of creative and imaginative element to this puzzle, a need to rethink how we value species and how we relate to them so that we can learn to care in new ways.

We need new practices of imagination and storytelling. That’s about our educational programs and biases against invertebrates in films and schools and all sorts of things. It’s about the way in which we often instrumentalize biodiversity to — even in the case of invertebrates — focus on the beautiful ones like the butterflies, or the useful ones like the bees, instead of really trying to cultivate a sense of appreciation for all these relationships that are going on all around us.

What I’ve tried to do in this book, in part, is to think about how snails inhabit their worlds, how they navigate and make sense, about snail socialities and reproduction, and all these fascinating things that are going on as a way of trying to thicken our sense of who they are and to create a greater sense of appreciation.

I think that kind of cultivation of a sense of appreciation and wonder is a transferable skill. If we can do it with some species, it can ripple out from there to help us to appreciate the wider world.

One of the things you write about are the “exclosures” — these fenced refuges for rare snails that have been constructed to try and protect them. While that program has been largely successful, you also question what happens if they’ve created an ark where the passengers can never get off. How do you grapple with the success of saving species if they’ll remain in captivity?

I think we do have to sit with that, and we do have to acknowledge that some species, like Achatinella apexfulva, have been lost in the ark and in these fenced exclosures — and others probably will be too.

So even if life in the forest again becomes possible at some point in the future for these species, it won’t be for all of them. I think we should hold onto that. I think that’s about an honest reckoning with what’s going on in the world around us.

I think we should grapple with the complexity of the situations we’re in. The cultural pressure to always share some good news stories isn’t always helpful and can be very dismissive and alienating for people who are really struggling and living — like the scientists in this case — in the midst of this ongoing loss.

Even if life in the forest again becomes possible at some point in the future for these species, it won’t be for all of them.

That’s why I end [the book] on this note of mournful hope that I think is really important. There are still possibilities here for a fuller sense of snail life, for getting snails back out into the world, but we really don’t know how that would be achieved at this stage.

There’s an element of bearing witness in this book and in a lot of my writing that’s about not trying to rush to the good news or to the solution but to try and honestly hold in our presence what has been lost so that we can learn from it, feel responsible for it. And also as an ethical obligation to those who have been lost, that they not be just forgotten.

Tara Lohan is deputy editor of The Revelator and has worked for more than a decade as a digital editor and environmental journalist focused on the intersections of energy, water and climate. Her work has been published by The Nation, American Prospect, High Country News, Grist, Pacific Standard and others. She is the editor of two books on the global water crisis.