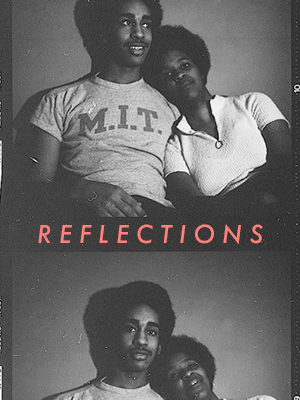

Reginald Van Lee: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT

Edited and excerpted from an oral history interview conducted by Clarence G.Williams with Reginald Van Lee in New York City, 21 March 1996.

I was born and raised in Houston, Texas. I was one of five children — the youngest child, the only son. I have four older sisters. My father worked for the government, my mother was just a housewife. She stayed at home and took care of the kids — dedicated herself to the children. Promotion of education is very important in our family. All of my sisters did well in school. All of us went to college. All of us got master’s degrees. So it’s one of those atypical, as people would like to think, atypical sorts of families. Family values, Southern values, religious but not overly eccentric in our family — not sort of crazy religious — but a solid sort of religious background, something like that. There was a lot of support in the family from the parental side. To this day I talk to my parents every day. No matter where I am in the world I call them, and that sort of stuff. I talk to my sisters at least a couple of times a month. I think that that had a lot to do with my getting through a place like MIT. When things were difficult, the notion of “Well, if I’m not successful here I have nowhere to go,” that was not even a problem in my mind. I could always go home, and my parents would tell me constantly, “If there’s a problem let us know.” That’s why I could push hard and build through the failure. I always had something to fall back on. That was my background.

What was your high-school experience in terms of academics and so forth? What were you involved in? What kind of success did you have in high school?

Well, I was one of those active kinds of folks. I was president of my junior class, I was editor of the yearbook, I was president of one of the other clubs, and a lot of that sort of stuff. I participated in a lot of the extracurricular stuff. I was a member of the Number Sense Club, which was like a math club. Each year I competed in the science fair that was in Houston, and worked it into my school. A couple of times I won sort of the top award in science and that sort of stuff. I was a good student. I did well in school and I was active in a lot of things. I was popular to the extent that people would be willing to talk to me — not popular like an athlete would be, but popular for academics.

Tell me about your experiences during your undergraduate days at MIT. Illustrate any highlights or reflect on issues in your life as a black student there.

Well, it’s strange because clearly my experience at MIT was a unique one compared to some of the other black students there. I came from a very sort of sheltered environment and a peaceful one. My mother was like overly protective, even though I was a boy and boys perhaps could do more. I had these four sisters before me and she was as protective of me as she was of my sisters. While I did a lot of extracurricular stuff on the academic side, I went to one or two basketball games — home games — and one or two football games — home games — my whole high-school experience. A lot of the sort of social stuff that other people did, I never really got a chance to do. I was a little bit of a bookworm in high school as well, so social aspects of high school weren’t particularly there for me. So, escaping to Boston from Texas and not having my parents over me and no relatives there to sort of tell me what to do, having this sort of freedom, and being in an environment at MIT where everybody was a little weird and a little bookworm, I was right at home.

Escaping to Boston from Texas and not having my parents over me and no relatives there to sort of tell me what to do, having this sort of freedom, and being in an environment at MIT where everybody was a little weird and a little bookworm, I was right at home.

I had a great experience there. I loved being in Boston. I didn’t go around the city that much, but just the whole academic environment and all of the schools around there. I would spend some time down at Harvard because I had some friends who were down at Harvard. We met in Harvard Square and Kendall Square. That was really exciting for me. I was fortunate enough to do well — to adjust. I didn’t have the academic pressures that other people, some other people, had because they were having a hard time. So as it ends up, the racial issue was not a big issue with me either, and I managed to have both black and non-black friends — but still clearly identify with being black. There is no issue in my mind what race I am. I mean, there were no illusions that everyone is wonderful and there is no prejudice in the world. I didn’t have that sort of illusion either, but clearly I was able to connect with some people who didn’t have any problems with the race that I was. I was able to build around an environment that was a pretty wholesome sort of environment. I had very good friends who I am still very good friends with and see on a regular basis. Those friendships meant a lot to me. I loved MIT. I had a great time. That’s one of the reasons why I try to get back to the school, because it really was a part of positive building for me. I know many of us black students don’t ever want to see the place again because it was not a source of positive building.

How and why did you choose your field or career that you’re in now? Was there anyone influential in that choice?

Yes. It’s a strange sort of story. I got my bachelor’s and master’s in civil engineering at MIT. During the summers I worked at Exxon in Houston and I had an offer from Exxon to come there permanently when I graduated. So when I graduated I went to Exxon. Almost from the minute I graduated from MIT, I decided that I probably didn’t want to do just engineering always. I had gotten this degree and I wanted to do something with it, but I wanted to try to find a way to do that and do things that I found to be a little more interesting. I didn’t know what “a little more interesting” meant at that point, but I knew there was something that could be a little more interesting. At the time I was graduating, there was a guy who was in the class before me — a black guy, Al Frazier had gone directly from MIT to Harvard Business School. He didn’t work between MIT and Harvard. For the extra year that I spent in graduate school at MIT, plus the year ahead of me, those were his two years in business school. I was graduating from MIT with a master’s in civil engineering and he was graduating from Harvard with a master’s. His offers were ten or fifteen thousand dollars a year more than ours. I didn’t understand what this was, so I said, “I need to go check into this business school thing, this Harvard business school thing in particular.” So while I was finishing my thesis at MIT, I also took the GMAT’s and was accepted at Harvard and Stanford. I deferred both of them. I deferred Stanford for a year and Harvard for two years because I really did need to work because I felt I’d borrowed all this money and I did need to pay it off. Exxon made me a sweet deal because I worked there for the summer and it was all going to be easy. I decided that if I couldn’t stand more than a year of working I would go to Stanford and if I could stand up to two years then I would go to Harvard. This was sort of my plan.

The thing that caused me to want to go to business school and eventually to do consulting, which is what I’m doing now, was I liked the technology aspects of my engineering background. I liked to do things in technology, but I didn’t want to be a pure research engineer. I really liked interacting with people and there wasn’t a lot of need for that in a pure engineering position. I wanted to be in a position where I could make a strong impact early on. I didn’t feel as though I could get that as quickly in engineering. I would have to go up a ladder and after some ten, twenty, however many more years perhaps I could make a big impact. Whereas with the business degree, doing more business management with the technology I could make a bigger impact sooner. It compelled me going into consulting because we’re working with clients at the CEO board level and making an impact early on. I mean, I’m not an old person. I know three or four CEOs and I’ve driven companies to major successes. That sort of impact I didn’t think I could make as quickly if I had stayed an engineer. The notion of what drove me from pure engineering through business school and into consulting was the need to mix the stuff that I liked about engineering with some other things that I wanted to do. The one who really had the biggest influence was Al Frazier. He probably doesn’t know to this day, but just that one conversation with him where he was talking about his job offers made me say, “Well, maybe I should think about this too.” I had never seriously considered business school at all.

What about role models and mentors in your studies at MIT as well as your career? Can you refer to any role models or mentors? I mean you’ve already mentioned a person who was very influential, but who else?

You know, I haven’t thought hard about it. Off the top of my head, there were people at MIT like Mary Hope and like Wes Harris, who was sort of an administrator then. It wasn’t a direct role model, because they weren’t engineers — well, I guess Wes was — but the notion of the presence that they had in the MIT environment and in the wider context of the world. The intelligence that they had, the concern they seemed to have for people in general — minority students in particular — gave me that encouragement. One, there is someone who is batting for you; and two, when I get to some position I should be batting for whoever as well. Just as they helped me, I had an obligation to help other people. If there was a position of importance in a place, even in a place like MIT, that a person can have and whatever context I move into, whether it’s academic or whatever, I could take on that sort of position. It’s almost, not to get too mushy, but almost be a beacon for other people trying to do things. That sort of inspiration helped me.

The notion of what drove me from pure engineering through business school and into consulting was the need to mix the stuff that I liked about engineering with some other things that I wanted to do.

In all truth, my biggest source of inspiration was my parents. My father was not an overly -educated man, but he did very well in life. He was a very intelligent man. He was very caring — like a caretaker for other people. The sad note is that my father passed December 16. He had a massive heart attack just recently. There isn’t a whole lot of sadness in my heart over that because he was a wonderful person to so many people. That was my inspiration. He wasn’t an engineer and he wasn’t a big corporate executive or any of that sort of stuff, but he had a lot of drive and initiative. He was very intelligent, a very caring type of person. My mother, who was much better educated than my father, chose just to raise her children. She thought that was the biggest impact she could make. By most people’s account, all of us have been very successful. My sisters are all very successful and I’ve done well. I know in large part that is due to the training that she gave us. She started me in school early. She sort of lied and told them that I was five when I was four. I started kindergarten when I was four. When I went to school at the age of four, I knew all of my alphabet, could spell my name, knew my telephone number, knew my address — you know, just things that other kids didn’t know. I was surprised looking at some of the kids around me — they didn’t know anything. My mother had taught us all of this. Some of the things she would do. Every day my mother would cut out articles from the newspaper on current events issues that she thought even at our young age we should be aware of and understand. She posted those on the bulletin board in our family room every day. That was the topic of discussion at dinner. At dinner you had to talk about current events. If you didn’t say anything, she would call on you like you were in school or something. So that sort of stuff caused me to always feel as though I had to achieve something.

Coming back to MIT again, what do you think was best about your experience there? What was perhaps the worst?

I think the best thing about my experience at MIT was the quality of education. I’ve had a chance to compare, perhaps unfairly, but I compare it to my Harvard Business School education and it just wasn’t as substantive in my opinion as the MIT education was. There were not a whole lot of politics going around at that level, whereas in other schools you get a political scene — getting the professors to like you and all that stuff, as opposed to where the work is and understanding. I think that’s one of the reasons I did as well as I did because it was much more of a meritocracy — two plus two is four. Good thinking and bright thinking was appreciated and recognized. That’s what I really liked about it best. I learned a lot at MIT about the subject matter of civil engineering, but more importantly about how to think beyond just the pieces of data that you’re given and how to assemble constructs and frameworks and logic and almost how to be a leader in that context. A leader is being someone who steps beyond the comfortable and into the uncomfortable, but still with a sense of comfort — that sort of thing. Maybe I’m being too ethereal, but those are the things that I took away and I swear it helped me.

I have a number of friends who had a hard time, took six or seven years to graduate, and now they’re doing just fine. Who even knows it took them seven years to graduate from MIT?

Now, what didn’t I like about MIT? I don’t know how much of a part MIT is in this, but I guess I didn’t like what it did to some people, especially some of the black people. It caused low self-image, a sense of worthlessness among some folks. It just sort of destroyed some people completely. Now part of me says if you’re sure of yourself, then the Institute can’t do anything to you; but then part of me says it seems as though there should be something the Institute could do to not allow that to happen so much. When I was there, as I recall, MIT had the highest suicide rate of any American school. I don’t know if they’ve cleaned that up now, but at that point it was high.

It was very high. You were around ’75 to ’79 and it was very high then. I think it’s gotten a little better, but it’s still up there in the top.

Yes, and so either there is something about the people you accept or there is something about the school itself, or both, that causes that sort of phenomenon. I mean, it’s not that big of a school compared to some state schools. But I think both on a serious basis and even on an absolute numbers basis our number of suicides are higher than so many other schools. I recall passing by the Green Building going over to west campus and they’d have the thing roped off and you’d see the blood spots where somebody jumped out. There’s something that needs to happen about that. Even though, as I recall, black students were a very, very small percentage of the actual suicide attempts, still the structure didn’t adhere to ease the pressure — it was something that was unattractive. I don’t know how to get my arms around this problem, but that’s the one thing that stood out in my mind.

Well, that’s very helpful. Based on your own experiences, including your work experience, and just life in general, is there any advice you might offer to other blacks who might be entering the MIT environment?

A couple of things. I don’t profess to have the secrets of the university — this is just one man’s opinion. I think it’s important that you try to have a sense of your own self first and foremost and if you’re willing to take a chance and be willing to fail and push hard to succeed, but you recognize that your value as a person is not wrapped up in grades you get at MIT or what any professor at MIT thinks about you. Strike a balance between being concerned and trying to strive and not ignore completely what MIT says about you, but on the other hand not putting all of the importance of your life in with the school books. In the scheme of things and in the balance of your life, you know, things can be just fine. I have a number of friends who had a hard time, took six or seven years to graduate, and now they’re doing just fine. Who even knows it took them seven years to graduate from MIT? If it took them seven years to learn it well, then so what, as long as you learned it well? So keeping that balance, separating the substance from what isn’t substance, and always keeping things in check that sort of way I think is important. The only other advice I would give them is to then get the most you can out of the Institute. You’re paying money to go there. Even if you’re on scholarship or something, there’s something you’re putting out to be there and so the Institute owes it to you to give you the best education you can get. Just trying to get over, scoot by, and just pass — that’s not smart because you can’t retrace those years again.

I want to shift to what you’ve learned about being successful business-wise as well as personal-wise. You’re unique because you deal with trying to help organizations to be successful, in general. What can you share with young blacks coming out of MIT, as well as with MIT itself, about what you’ve learned that will help them to be successful? When you look at your experiences in helping management to be successful, what advice would you give in that regard — that is, business-wise as well as personal-wise?

Well, I’m actually going to cheat. There was a speech that Bill Gray, who’s the chairman of the United Negro College Fund, gave to a bunch of black folks at Booz Allen some time ago. The question was, “What is the formula for success?” I thought he captured it and I carry it around so I can always share it. This was for black people in particular, but I think it applies to everybody. The first thing is a sense of what you call positive aggressiveness. You’re sort of putting the bitterness aside. Nourishing bitterness — that’s not going to do you any good. That’s part of what I said — to really go aggressively for the things you want in life and be very positive that you can achieve some things and really try it. The second thing he says is a deep optimism — you know, this whole thing of Hannibal going through the Alps with the elephants, and all this other stuff. He told this joke about somebody saying, “Well, if you’re going to go and conquer them, what about the Alps?” Hannibal’s response is, “What Alps?” This sort of deep optimism is really quite intense. That’s hard sometimes for people to find in themselves, but you have to do that. When you look at some of the things that people have accomplished, you can argue there is no way that should have happened.

So there’s got to be some optimism if you can find it. Some things do happen in spite of the leadership now. Then clearly the thing that is true for black people is this notion of over-performance — that, like it or not, you really have to over-perform. You have to do three times better than the other person did. It calls me back to this line from the play, “Having Our Say,” about the two Delany sisters. One of them made the comment that black people have to be two times as good as the white folks. Just look at Dan Quayle. If he had been black, he would have been a janitor or something, but it’s true, it’s true. You can get all upset about that and say that’s not fair and grind yourself into a fear of it, or you can just accept reality and go for it. It’s almost like if you’re born with one hand. You’re a person without it all of your life, you just keep going with the other hand you have. So it’s all performance.

You don’t need to be apologetic to people about the fact that you’re black. That’s something I make a point of never being apologetic because I’m not ashamed of it, I’m proud of it.

The fourth thing he said is, “You should have pride,” which is, you don’t need to be apologetic to people about the fact that you’re black. That’s something I make a point of never being apologetic because I’m not ashamed of it, I’m proud of it. And to not be in denial either. This doesn’t mean you have to get out and say, “I’m black, I’m black …” and wear a black glove all the time — the notion of recognizing that you are black and behaving in the way that people sense that you are. If you don’t have that pride in yourself, it’s not going to work. People are going to wonder after a while, “Why isn’t he proud?” There must be something behind that. The last thing he said was that we need to establish relationships with each other and learn from each other and learn from others. You should never get to the point where you feel as though you can’t learn from other people, whether they’re subordinate to you or not, and that you don’t have a need for a relationship with other people. This doesn’t mean you have to make friends with everybody, but there are all sorts of bases for relationships and it’s really important to have those relationships. Those were the five things that he outlined. I’ve used these with clients. I give them a little scrap of paper.

That’s just beautiful. Now this brings me to the last question. MIT is now going through a re-engineering process; what advice or caution would you give to MIT as it goes through this change? I noticed in your work and particularly your research — even in your first research paper — you talk a little bit about organizational change and what you have to be careful about and things of that kind. I was very interested in what you would say MIT should be very careful about as they do this whole re-engineering process.

I want to inject a little bit of levity. I don’t know if you read my famous sign out there: “Change- management is like teenage sex. It’s on everybody’s mind all of the time. Everybody talks about it all of the time. Everybody thinks everyone else is doing it. Almost no one is really doing it and the few that are do it poorly, think it will be better the next time, and don’t practice it safely.” That’s one of the jokes, but it’s true. My caution to companies and MIT in particular when they are going through change is first, change is a process. It’s not as though it’s going to happen all at once. It is a process, and some people are onto the process and some people are not. In my work I use a formula for change which says change equals dissatisfaction plus vision plus practical first steps. What we’ve discovered is, if not enough people are dissatisfied enough with the current situation they’ll never change. So unless you get the people at the top or some combination of people at different levels dissatisfied enough with the way things are, you’ll find that they will really fight — they will resist change — even though sort of in their gut they think it might be better to do that. They have developed such a comfort, even in this uncomfortable situation, that they can’t move out from it. In our work a lot of times part of the analysis is around explaining to you why you’re in trouble or explaining to you why you could be much better off if you change. So we’re trying to get you to be dissatisfied, really dissatisfied with the way things are right now. We found that when we’re not successful in convincing people or convincing enough people or convincing the important people that they are really dissatisfied, that was why. They’ll spend lots and lots of money; I had a client who spent three million dollars on us doing some work that would require some change. We finished the work and it was the start of the implementation. They stalled the implementation and they had an internal group to redo all of our analysis for a whole year and they came back to the same conclusions, and still he wouldn’t change. He finally confided in me that when he bought that work he never intended to change at all, but that he had all these pressures around him and that it looked good if he launched this stuff. People would assume that if he was spending three million dollars he…

… must be serious about it.

He was willing to spend three million dollars just to get people to leave him alone for a while. What he hoped was the business situation would get better in that time period and then people would say, “Oh, you don’t have to change anything.”

Then he could put it in the wastebasket.

There was no real dissatisfaction. He was dissatisfied with people bugging him and so he was willing to do something about that, but he wasn’t willing to engage in the change. So that’s the dissatisfaction. The other part of the analysis that we do is to come up with what the vision for the company should be. What MIT’s vision should be is something that has to be sorted out. Where do you want to be compared to other universities, or whatever your goal and missions are, whatever you want to call it? Unless you are clear on that vision, unless it is articulatable so that everybody can understand it in common terms, you may not go far. It doesn’t have to be five words. Some people say, “It has to be five words. I want you to pick five different things.” It has to be something everybody can engage in because the best operating institution is the one where everyone is engaged in the vision. If I’m just a secretary or a janitor or a whatever, I know my role in this big vision. It’s really important that that’s in place. So if I now go to MIT just with those first two things — the dissatisfaction and the vision — it is hard for people who have historically been successful to accept either that they are not successful enough or that they may not be successful going forth.

So I don’t know where the mindset of the leadership of MIT is in really accepting the fact that they are dissatisfied with the current situation and want to change it. I would caution them to put a mirror in front of their faces and ask the question, “Is the pain of staying where I am greater than the pain of change?” If you can’t answer it that way, then don’t waste your time and change the ways. On the vision part, have we really come to a vision that captures the good things of the culture, gets rid of the bad things of the culture? It is clear enough and specific enough and not full of a whole bunch of political terms and mish-mosh, but clear enough so that people can really engage from the top all the way down in the administration? The last part of my equation is first practical steps. If I’m here now and my vision of success is over there and I tell you what we want to be, but I can’t give you any first steps you can make toward it, the empty container is sort of going to collapse on itself. It’s too much. People can’t absorb it. It’s too much. You’ve got to know where you’re going. You can’t just give me the little steps and I don’t really know where I’m going, but I can’t just give you where I’m going without the first practice steps. So the walk before you run sort of makes the plan too.

The driving force for the re-engineering, as I’ve always heard from key people, has been the financial matter that has caused us to get reductions in our research funds. Consequently, we have to deal with that loss of funds that we probably won’t get back; we’re going to have to operate from a much leaner base.

To fix your problem, you can’t just fix the cost side of the problem. There’s a side of the problem that we call capabilities, which asks how do we grow the institution, how do we get more revenue — not just how do we cut costs, but how do we grow more revenues? If in your re-engineering you don’t build new capabilities, if all you do is downsize or get rid of costs, then so many years later you’ll have the same problem. More often than not what people really have is a revenue problem. If the Institute would charge more money for tuition or could somehow attract other revenue sources aside from the federal funding or whatever they’re getting right now, then even that little money over there is paying people more money and you wouldn’t see it because the revenue solutions can always mask cost price. It could be better to both fix the cost price and build the revenue, but oftentimes in re-engineering all people have focused on in the past has been the cost factor. That’s not a sustainable sort of strategy.

Reginald (Reggie) Van Lee is a philanthropist, an arts advocate, and retired Executive Vice President of the global management and technology consulting firm Booz Allen Hamilton.