Notes on the Rituals of Insomniacs

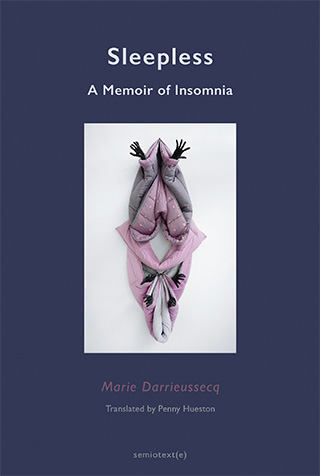

Plagued by insomnia for 20 years, in her book “Sleepless,” Marie Darrieussecq turns her attention to the causes, implications, and consequences of sleeplessness: a nocturnal suffering that culminates at 4 a.m. and then defines the next day. “Insomniac mornings are dead mornings,” she observes. Prevented from falling asleep by her dread of exhaustion the next day, Darrieussecq, a leading voice in contemporary French literature, turns to hypnosis, psychoanalysis, alcohol, pills, and meditation. Her entrapment within this spiraling anguish prompts her inspired, ingenious search across literature, geopolitical history, psychoanalysis, and her own experience to better understand where insomnia comes from and what it might mean. The following text is excerpted from “Sleepless,” published by Semiotext(e).

So instead of drinking every night, I started to increase my sleeping rituals. And to collect more reading matter on the subject. It’s common knowledge that Kant was a champion obsessive, especially about his sleep: Whatever was happening, he went to bed at quarter to ten and got up at five minutes to five.

Long practice had taught him a very dexterous mode of nesting and enswathing himself in the bedclothes. First of all, he sat down on the bedside; then with an agile motion he vaulted obliquely into his lair; next he drew one corner of the bedclothes under his left shoulder, and, passing it below his back, brought it round so as to rest under his right shoulder; fourthly, by a particular tour d’adresse, he operated on the other corner in the same way; and finally contrived to roll it round his whole person. Thus swathed like a mummy, or (as I used to tell him) self-involved like the silkworm in its cocoon, he awaited the approach of sleep, which generally came on immediately.1

Without managing to accomplish that feat, I tuck my doona into the end of the bed in a very precise way: not too tight (that hurts my feet), not too loose (my feet get cold). Henri Michaux describes this unpleasant problem thus: “Sleep is very difficult. First of all the covers are always incredibly heavy; the bed-sheets alone are like sheet metal. If you take everything off, everyone knows what happens then. After a few minutes of sleep — undeniable for that matter — one is shot into space.… Consequently, bedtime is unparalleled torture for so many people.”2

You can see that when I’m shot into space like that, even my astrophysicist husband has trouble sleeping with me. I am unbearable. I wear earplugs and I turn off anything that emits light. I close the shutters, I carefully pull the curtains shut; my door is covered by a wall hanging. In hotels, I wear an eye mask. I’m frightened of going to Nordic countries, with their bare windows, their individual doonas even on double beds. I leave a whole collection of herbal teas cooling on my bedside table and take two or three sips. No bladder could ever account for my innumerable comings and goings. I put lime-blossom essence on my pillow. I tie a warm scarf around my neck in winter and a sheer one in summer. Definitely no patterns on my white sheets. I have two sets of the same pajamas, so I can change them without any disruption; they bring me good luck for sleeping. Georges Perec: “Vowl is willing to try almost anything that might assist him in dozing off — a pair of pyjamas with bright polka dots, a nightshirt, a body stocking, a warm shawl, a kimono, a cotton sari from a cousin in India, or simply curling up in his birthday suit, arranging his quilt this way and that. 3

I do a few Pilates stretches, always the same ones, with the same little inflatable ball that I also take with me when I travel. I meditate, or at least I try to. If I could, I would pray.

In “Life: A User’s Manual,” Perec again, a character called Léon Marcia gets lumbered with the liturgy of insomnia: “For hours and hours the old man paces up and down in his bedroom, then goes to the kitchen to get a glass of milk from the fridge, or to the bathroom to rinse his face, or switches on the radio, at low volume but still too loud for his neighbours, to listen to crackling broadcasts from the other end of the world.”4 He’s so agitated that his son has to cover the party wall with strips of cork.

Here is Philip Roth in “Asymmetry,” the novel by Lisa Halliday: “He would switch off the phone, the fax, the lights, pour himself a glass of chocolate soymilk, and count out a small pile of pills. ‘The older you get,’ he explained, ‘the more you have to do before you can go to bed. I’m up to a hundred things.’”5 The glass of chocolate soy milk stayed with me. I tried out several brands. The vanilla-tasting one is thick and sugary, very palatable; it weighs a little on the stomach but digestion is conducive to sleep. It’s no substitute for the Saint-Émilion, but it keeps my mind off things and it’s a lot cheaper. I can use pretty cups, or even glasses, although I don’t go as far as stemmed glasses. And soy milk is apparently excellent for women of my age. In short, Philip Roth has found a female fan.

Des Esseintes, Huysmans’s famous character, also employs innumerable extreme measures: “He had without success tried to install equipment for hydrotherapy in his dressing-room.… Since he could not be scourged by jets of water which, smacking and drumming directly at his dorsal vertebrae, were the only thing powerful enough to quell his insomnia and restore his tranquillity, he was reduced to brief aspersions in his bathtub or sitz bath, to simple cold affusions followed by vigorous rubdowns by his manservant with a horsehair glove.… To amuse himself and fill the interminable hours, he turned to his boxes of prints and sorted his Goyas.”6

Not everyone has Goyas to arrange. But between downing a glass of hot milk and immersing oneself in an icy bath, the rituals of insomniacs are often sadomasochistic: Quake in your boots, you wretch — now you’re going to sleep! André Gide, in his journal: “Insomnia, I am struggling as best I can; force myself to ‘take exercise’; to walk, to take a cold tub as soon as I return from a ‘health walk.’ … Nothing does any good; each night is a bit worse than the preceding one.”7 The protagonist in Mari Akasaka’s novel “Vibrator,” which I like a lot, makes herself vomit in order to sleep.8

I had never heard of that. Something to do with endorphins. And in Chuck Palahniuk’s “Fight Club,” the narrator, haggard with insomnia, attends meetings of patients suffering from shocking illnesses he doesn’t have, invasive cancers, parasitic brain infections … and discovers that listening to them puts him to sleep.

Henri Michaux: “All night long, I push a wheelbarrow … it’s so cumbersome. And on this wheelbarrow sits a huge toad … it’s so heavy, and its body gets bigger as the night goes on.”9

Marie Darrieussecq is one of the leading voices in contemporary French literature. Her first novel, “Pig Tales,” was a finalist for France’s prestigious Prix Goncourt in 1996 and became an international bestseller. Her 2013 novel “Men: A Novel of Cinema and Desire” received the Prix Médicis, and her luminous, voluptuous portrait of the artist Paula Modersohn-Becker, “Being Here Is Everything,” was published in English by Semiotext(e) in 2017. This article is excerpted from her book “Sleepless: A Memoir of Insomnia,” also published by Semiotext(e).

- Thomas de Quincey, Thomas De Quincey’s Works, vol. 3, Last Days of Immanuel Kant and other Writings (Edinburgh: Adam and Charles Black, 1871)

- Henri Michaux, “Dormir,” in OEuvres complètes, vol. 1, ed. Raymond Bellour (Paris: Bibliothèque de la Pléiade,1998)

- Georges Perec, A Void, trans. Gilbert Adair (London: Harvill, 1994)

- Georges Perec, Life: A User’s Manual, trans. David Bellos (London: Vintage, 2003)

- Lisa Halliday, Asymmetry (New York: Simon and Schuster, 2018)

- Joris-Karl Huysmans, Against Nature, ed. Nicholas White, trans. Margaret Mauldon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009)

- André Gide, journal entry, December 1921, in Journals, vol. 2, 1914–1927, trans. Justin O’Brien (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2000)

- Mari Akasaka, Vibrator, trans. Michael Emmerich (London: Faber and Faber, 2005)

- Michaux, OEuvres complètes