Masters of None: The Flawed Logic of One-Size-Fits-All Education

In 1968, the educational psychologist Benjamin Bloom developed an instructional strategy that he called “mastery learning.” Bloom based his strategy on a simple idea: Students learn best when they’re allowed to master basic subjects before they tackle more advanced ones. Mastery learning requires educators to provide students with the time necessary to master materials at their own pace, which means that students should be treated as individuals who have unique backgrounds, learning preferences, and pedagogical needs.

But Bloom didn’t propose this individualized style of learning as just a theoretical possibility. He conducted research that proves it works. Students taught using mastery learning techniques, he discovered, outperformed students trained in conventional one-size-fits-all classrooms by 400 percent. Bloom hated the thought of all the lost potential and railed against existing approaches. “Much of the effort of the schools and the external examining system,” he wrote in his 1968 article, “is to find ways of rejecting the majority of students at various points in the education system and to discover the talented few who are to be given advanced educational opportunities.”

Sound familiar?

During the past 50 years, higher education has relaxed its slavish conformity to grading based on forced curves, but the concept lives on in introductory, “weed-out” courses that are designed to cull the herd of its weaker members. The former acting governor of Massachusetts and educational reformer Jane Swift summarized her concerns about such courses in an April 2021 tweet:

Reason gazillion we don’t have more STEM grads? Daughter (currently has a 4.0 in her math major) being told Computer Science req’d course is “impossible”—peers say avg for first exam is 15%. Isn’t that an indictment of the professor?

Yes! Or at the very least, it’s an indictment of the system. That’s certainly what Bloom’s research suggested. In his paper, Bloom went on to talk about how mastery learning (paced instruction, personalized review) improves student outcomes, and why it’s stupid to assume that a student who might take longer to grasp a particular topic is, well, stupid. “If we are effective in our instruction,” he wrote, “the distribution of achievement should be very different from the normal curve,” adding, “If the students are normally distributed with respect to aptitude, but the kind and quality of instruction and the amount of time available for learning are made appropriate to the characteristics and needs of each student, the majority of students may be expected to achieve mastery of the subject.” Sounds pretty reasonable to me.

Students taught using mastery learning techniques outperformed students trained in conventional one-size-fits-all classrooms by 400 percent.

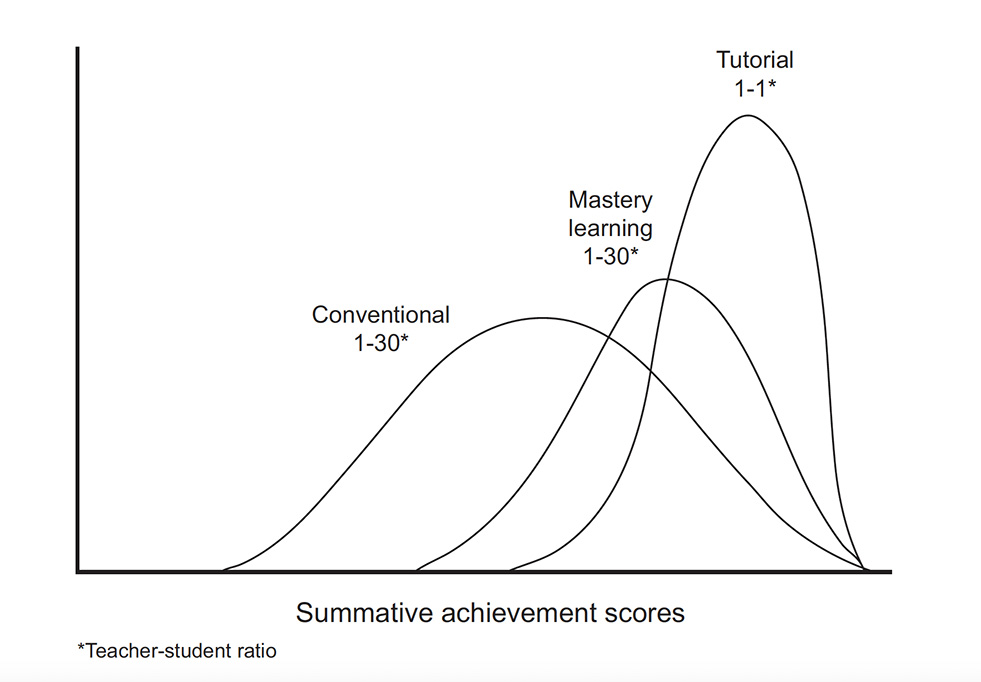

Bloom continued to explore the potential of mastery learning and in 1984 published an article in which he discussed the advantages of combining it with one-to-one tutoring. What he found — as shown in the graph below — is that while mastery learning on its own can deliver a one standard deviation increase in student performance over conventional instruction, combining it with one-on-one instruction increases the mean of student performance by two standard deviations above the mean of conventional instruction. What this means in practice is that the average student who receives a combination of mastery learning and one-on-one instruction performs better than 98 percent of the students who receive conventional instruction.

The implications of this shift are profound. Consider a class of 100 students. Bloom found that when the class was taught using conventional instruction, two students received an A+ and that when those same students were taught using a combination of mastery learning and one-on-one instruction, 48 more of them achieved A+ mastery.

All of this raises an obvious question: If mastery learning and one-on-one learning are so much better than traditional classroom instruction, why don’t we use them more? The answer, unfortunately, is just as obvious: Mastery learning and one-on-one learning aren’t cost-efficient at scale.

In short, the problem comes down to scarcity — a scarcity of instruction that can be tailored to the individual needs of students.

Okay, so you’ve got lots of students and relatively few instructors. The instructors are the scarce resource here, and they’re bound in space and time. To learn from them, you have to be on the campus where they teach and in the classroom when they teach. A single professor teaches the same content to many students from, say, 9 a.m. to 10:20 a.m. on Tuesdays and Thursdays, from early September to mid-December, in room 1206, in Hamburg Hall, on Carnegie Mellon University’s campus, in Pittsburgh.

This scarcity creates two broad categories of problems — one for instructors and one for students. Let’s take those in turn.

The problem for instructors, at least for those who altruistically care about the quality of their teaching (more on that in a second), is that they don’t have time to give their students the individual attention that they deserve — and that mastery learning demands. When I teach to a room of 30 students, I’m quite sure that three to five of them are bored (and could go faster) and three to five are lost (and need more time grasp the concept). The challenge is that I usually don’t know which ones they are — and even if I did, I wouldn’t be able to do much about it because I’m busy trying to keep the middle 20 students in the class happy and engaged.

This problem is even worse in classes where students have diverse backgrounds. One of the hardest classes to teach in the management program I’m a part of is Introduction to Accounting and Finance. Why? Because instead of just a few students in the tails of the distribution, this class typically has lots of students with strong finance backgrounds, and lots of students with no finance background. So instead of just a handful of students who are either bored or lost, introductory accounting professors know that most of their students fall into one of those two buckets — and in a single 80-minute lecture, they just can’t give each individual student what they need.

There’s a related problem that arises from instructor backgrounds. Like most professors, I’m regularly asked to teach topics that don’t align with what I’m most qualified to teach. To achieve tenure in the academy, you have to become a world-recognized expert in a specific area of study. In my case, that meant investing a great deal of time and effort in becoming an expert in how information technology and digitization impact structure and competition in markets.

In short, the tenure process produces specialists, and that’s a good thing — at least until you get into the classroom. At that point, you discover that there aren’t enough people on any given college campus to make it economically efficient to deliver a 14-week class on, say, the strategic and economic implications of technological change in digital markets for entertainment goods. As a result, educators who are trained as specialists are forced to teach as generalists. This means we have to convey our colleagues’ expertise secondhand. That’s a lot of work, and sometimes it makes me feel like I’m a one-man band playing a bunch of instruments poorly instead of playing my preferred instrument well. Wouldn’t it be better — for me and for my students — to cut out the middleman and allow students to learn directly from the experts on a particular topic?

Okay, so there’s scarcity in access to experts on different topics. But there’s also scarcity when it comes to experts who study the same topic. Consider the research that Harvard Business School professor Anita Elberse and I have conducted on the managerial implications of what’s known as the Long Tail — the low-level but cumulatively significant sales of niche products that become possible when you move from physical stores with limited shelf space to digital stores with unlimited shelf space. I have a world of respect for Anita’s intellect and research, but I disagree with her conclusions about the strategic importance of the Long Tail for media executives. This creates some awkwardness for me when I talk to my students because, given my biases, I feel like I give Anita’s position short shrift. Wouldn’t it be better if my students could hear me make the best case for my position and hear Anita make the best case for hers? Why don’t we do that? Because Anita teaches in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and I teach in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and for both of us, time is scarce.

Now that you know how scarcity makes my job difficult, let’s spend some time looking at the problems instructional scarcity creates for students — you know, the people who are often paying $60,000 or so a year to receive an education from me and my colleagues.

Some are easy to identify. In large, impersonal lectures, students can easily become bored or lost, neither of which is optimally conducive to learning. Similarly unsatisfactory is taking classes from instructors who have to muddle through when teaching subjects that fall outside of their areas of expertise, or instructors who, consciously or unconsciously, present the ideas of others in a misleading or biased way because they disagree with them.

Then there’s the role an instructor’s gender and race can play in student outcomes, a burgeoning area of academic research. In a 2021 paper published in the Journal of Marketing Research, for example, two University of Michigan faculty members studied whether female students benefit from having female professors. Specifically, they looked at the grades of undergraduate students at the business school of a public midwestern university and noticed that the grades of female students in quantitative classes were significantly lower than those of their male peers, even after controlling for the students’ measured aptitudes, grade-point averages, family backgrounds, and demographic characteristics.

But here’s where things get interesting: that performance gap virtually disappeared when those female students were taught by a female professor. Why? According to the authors, it’s because, at least for women, instructors of the same sex “increase female students’ interest and performance expectations in quantitative courses and are viewed as role models by female students.”

A 2010 study of the performance of male and female cadets at the United States Air Force Academy came to a similar conclusion: Taking a math and science class from a female professor eliminates the gender gap between male and female students in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) classes, and significantly increases the likelihood of women graduating with a STEM degree. These papers aren’t saying that women in technical disciplines benefit from always having female instructors. Rather, these studies show that female students in subjects that have historically been dominated by men benefit from having some female instructors who can mentor them and give them examples of success among people who look “like me.”

Studies show that female students in male-dominated fields benefit from female instructors as mentors and role models.

Other papers have found similar results for underrepresented racial and ethnic minorities. A paper published in 2014 in the American Economic Review titled “A Community College Instructor Like Me” noted a significant gap at community colleges between the dropout rates and grade performance of white and underrepresented minority students — and found that the gap closed by as much as 50 percent when classes were taught by instructors who themselves were from an underrepresented group. I could cite other studies, but I suspect you get the idea: Underrepresented students do better when they are able to identify with the person who is teaching them. The problem underrepresented students in my class face is that my identity is fixed in such a way that I can’t give them this opportunity.

Another problem students have when access to instructors is scarce is this: they have a tough time getting into classes taught by the most popular professors. At one level, this is just a numbers game: Professors are paid to teach a certain number of classes per year and can accommodate only a certain number of students in those classes. But there are other factors to consider — including, perhaps not so surprisingly, faculty egos.

Not long ago, Steven Levitt, who teaches economics at the University of Chicago and is a coauthor (with Stephen Dubner) of the bestselling “Freakonomics,” told a funny story to make this point, which itself highlights a larger point: When it comes to instruction, scarcity is sometimes manufactured. For years, whenever Levitt taught his popular Economics of Crime class, he had to limit it to roughly 80 students because that was the maximum capacity of the biggest lecture hall available to his department. He found that very frustrating. What if a student came to Chicago with a specific interest in this class but each year was closed out? It didn’t seem fair, so Levitt finally made a bit of a stink and got access to a lecture hall that seated 300 students, which filled up quickly. Imagine his surprise when, the following fall, he learned that he would once again be teaching his class in the smaller lecture hall.

To an economist, the decision made no sense. The demand was there, so the supply should be too. When Levitt went to his department chair to complain, the chair said, “Well, the problem is, all the other faculty members got really upset because there were hardly any students in their classes, and they complained so much that I’m going to lower you back down to 80 again.” To which Levitt responded, “This is the University of Chicago Department of Economics, and our solution is to . . . not let people have what they want?”

This kind of artificial scarcity isn’t just frustrating — it’s counterproductive. If the goal of education is to maximize learning, then the system should be designed to connect students with the best instructors for them, not to protect faculty interests or maintain outdated structures.

Bloom’s research pointed to a way forward decades ago. The challenge now isn’t whether we can make education more personalized, more effective, and more equitable. It’s whether we’re willing to let go of the assumptions and constraints that keep us from trying.

Michael D. Smith is J. Erik Jonsson Professor of Information Technology and Marketing at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Public Policy and Management. Smith is coauthor of the book “Streaming, Sharing, Stealing: Big Data and the Future of Entertainment” and author of “The Abundant University: Remaking Higher Education for a Digital World,” from which this article is adapted.