Jennifer N. Rudd: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT

Edited and excerpted from an oral history interview conducted by Clarence G. Williams with Jennifer N. Rudd in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 30 April 1996.

I’m from Peoria, Illinois, and I’m the second of nine children. My parents were originally from southern Illinois. We settled in Peoria because my father, after being in the service, was able to have his college education paid for on the GI bill. He was delayed in entering the University of Illinois because of some problem, so he went to Peoria where there is this school called Bradley University. He was at Bradley University. That’s where we ended up living. I went to public school. We lived on sort of the outskirts of town in a little black community near the public stadium. My father was an architectural engineer, one of the few black engineers in Illinois. That was an interesting experience.

Particularly at that time.

Yes, that’s right.

What years are you talking about, approximately?

I remember he was in school when I was born in 1946, so I guess he graduated maybe a year or two after that in architectural engineering.They had a program parallel to the Tuskegee Airmen, by the way, for engineers, that was based at Prairie View College in Texas and that recruited talented young people from the armed forces — the Army, in this case — and collected them there. My father had some very interesting stories to tell about the fantastic individuals he met in that program. He was a communications engineer/radio operator in the Army, so he was able to go to college.

In any case, we lived on the outskirts of town and as a benefit of that, I guess, I went to the suburban high school, which was clearly the best physical plant and had the best teachers and the best programs in the area. So I did go to a very good public high school. When I was in high school, my mother became ill with cancer and we took turns caring for her. She died over a fairly short period of time. She became ill in January and passed on by June. So, we had taken turns taking time off from school to spend with her. One of the things my father told me was, “You need to go to college and find a cure for cancer.” So I remember thinking about doing medicine in those days and the counselors had encouraged me to do so. They said specifically, “Yes, this will give you an opportunity to help your people.” I felt I was being shunted into an area that they thought was appropriate for me because I was black. So, I did everything but go into medicine at that point, which is interesting. Now, I’m a physician. But at that point, I said, “I’ll do biochemistry or something along that line.”

“When people would ask me where I wanted to go to school, I would say, ‘MIT.’ They would laugh and I would say, ‘Why are they laughing? It seems like a perfectly good place to me.'”

I read a brochure about MIT, a small pamphlet. It was bigger than a pamphlet, it was a little thick brochure. I fell in love with the school on the basis of that reading. When people would ask me where I wanted to go to school, I would say, “MIT.” They would laugh and I would say, “Why are they laughing? It seems like a perfectly good place to me. It seems like a very nice place.” I was very fortunate because I applied and got in. I think there were many students in my high school who were in the honors program with me who had applied there. I was the only one who was accepted, though. So I was pretty lucky. There was another fellow in my class who got into Harvard and had come. I saw him a few times while we were here.

How large was your high school class?

I’m trying to think now, but I think there were about 1,800 students in the whole school, if I have that correct. So, it was a pretty good size.

How many, approximately, black students were in your class?

My elementary school, because of the segregated housing in those times, was the only school that fed blacks into the high school. Those were people who lived within a few blocks of my house. So there were about 25 blacks, all of whom came from the one elementary school. The other black students in my class went to elementary school with me.

So all of you knew each other.

Yes. I think maybe out of seven or eight students who entered ninth grade, about four or five of us graduated. Many of the girls fell by the wayside with premature pregnancy, that sort of thing. I was the only black in the honors curriculum.

So, essentially you did exceedingly well while you were in high school.

Yes.

The high school, as I understand it, was clearly very predominantly white.

Right.

Did you have any teachers who stand out in your mind as role models or mentors of any kind?

I don’t recall having a single black teacher in elementary school or high school. My favorite high school teacher was my math teacher, who I had for four years — Mr. Moser, who was trained in Indiana. Another favorite teacher was my fourth-year English teacher, Ms. Rukgaber. We did some interesting things on philosophy and other things, besides just the routine grammar, that I enjoyed very much that senior year. Of course, the science teachers were fun to be around — biology, physics. But my math teacher was my favorite teacher.

You had him for four years?

Right. He taught the honors classes.

He must have been very good because you really had a good background to prepare you before you went on to college.

In those days, we got up to calculus and then we had kind of a self-taught program that required ten of us between junior and senior year to teach ourselves some calculus over the summer, which was interesting. We had a little bit of that. So, it was okay for preparation at the time. I think high schools now are beyond that even at the high school level. Unfortunately, later on, that strength in math was a major downfall and I’ll tell you about that when we get to it.

That should be interesting. Now, you said that basically you found out about MIT through this brochure, for the most part, and that it was very attractive. What did you like about the brochure? Can you recall?

I don’t recall specifically, but it just probably spoke in very general terms about the Institute’s mission and goals and about how it was a wonderful place to go to learn and really be creative. I was just very much taken by it and I said, “That’s where I want to go.” I had visited the University of Illinois. That was another choice of mine on the school-sponsored tours — trips that we went on when they had the science fairs for high school students, and you’d go and spend the day. I’ve been on the Bradley campus locally and my older sister attended Bradley for a short time, so I had some interaction there. I probably applied there also. I don’t know what it was about that brochure, but it seemed like a nice place to be. At that point, you may know, they had just built the first tower of McCormick Hall and they were very interested in increasing their women student enrollment. Prior to that, the women students lived in a few facilities across the river. They had just increased their capacity to have dormitory space for women students on campus. I think that was a time that they were actively looking for more women students, too.

Now, this was what year?

1964.

Did you visit the campus before you actually came?

Oh, no. My first plane ride was when I left home with my bags to come to school, to MIT. It was a little propeller plane that went from Peoria to Chicago, and I cried all the way from Peoria to Chicago. I was still wiping the tears away because I was taken aback by the experience of it all — being up in a plane, my first experience in a plane.

You were courageous, though.

I guess so. It was worth it. It’s hard to forget that because this was your first plane ride.

“My first plane ride was when I left home with my bags to come to school, to MIT. It was a little propeller plane that went from Peoria to Chicago, and I cried all the way.”

My first time away from home. I had visited relatives in Chicago, relatives in Cleveland, and even stayed for a while in both places with them, but by auto travel. This was the first plane ride.

You went through Chicago and I assume you got a flight from Chicago to Boston, and you got here. What were the highlights of that experience with MIT that first year?

Well, even that first week was great. It was very interesting because they had a very good program for freshmen to come a few days early. That’s very important, I can see, for incoming freshmen to get oriented and to have people just there to welcome you by yourselves first. Then there was the whole series of programs over the next few days to get people oriented to the campus and parents mostly bringing other students in. That’s when I met Alan Gilkes, our classmate, and his mom and dad. They took us to lunch or dinner one day. I met Shirley, of course. We were on the same floor, Shirley Jackson and I. I met her in the dorm. Different events they had in the first part of the school year, to go to different dorms for social events and so on, were kind of fun. Meeting the other women students, they were something. I was very impressed with how verbal they were and how they were so aggressive in conversation. I was very naive, very shy, and didn’t know really how to express myself in a group and be aggressive with anyone in groups. I was very impressed with these New York, New Jersey women. They were real bold and outspoken and forward.

Were these black students?

No. Shirley and I were the only black females, and I think there were seven other fellows in our class.

You and Shirley may have been close to the first black women to be there. Do you have any sense about that?

I don’t know if there were ever any other undergraduate women, but I understand that we were the first two African-American women to graduate from MIT. Now, whether or not others took undergraduate courses, I don’t know, at some point without matriculating.

Well, you are a very key person. You and Shirley are essentially the two first black African-American women to finish MIT. Have you ever thought about that?

Yes.

Tell me more.

I was surprised that I could be a first at something, you know, at that time and I just thought what a shame it was. I remember being very interested in the previous African-American students who had been there and hearing about them and what areas they went into, where they had come from. One in particular, whose name I don’t recall at the moment, was one of those gifted, talented people who was not only brilliant, but also a great athlete who had been there and graduated, I think, the spring before I started in the fall. I think he played basketball. That’s why we heard about him, because one of the sophomore students organized the MIT cheerleaders for the first time. This is interesting, because eleven people tried out and eleven people made it. We had something for everyone here, there’s a place for everyone. Nine cheerleaders and two alternates — everybody made it. So, it was fun to go to the games and that got me interested in asking about other black students who had come through the school.

When you look back now at the undergraduate days there, reflect on the issues in your life as a black student and particularly as a black woman. There were no other people like you then.

Yes. Where to start? In a racist society, one of the horrible things that happens is that people who are oppressed buy into their own inferiority. Illinois is a lot like the South. My high school, I mentioned, was predominantly white. There it’s sort of more black and white, unlike the East, where you have a lot more multicultural diversity and tolerance and appreciation of different cultures. People have lived for maybe several generations since they immigrated and they kind of merge into that Wonder Bread and bologna white middle-America culture. They buy into the American dream and all of that sort of thing. But clearly people who are physically, visibly black stand out as exceptions. If an Asian or East Indian should come to town and wear their native garb, they’d stand out. A big thing is even made of the foreign exchange students in the high school who were Caucasian, but have accents and have interesting dress and so on. I was excluded from a lot of things in high school, such as the social dance. My father refused to allow me to sit through it, so I usually had a study hall during that time or other things where they would separate us out and take the black fellows out of their class to partner with us when we had a session in dance in gym class and that sort of thing. I came here with a lot of stains and scars of the racist experience I was growing up in, along with the juxtaposition of the poverty that we lived in next to the wealthiest people in town where we went to high school.

“In a racist society, one of the horrible things that happens is that people who are oppressed buy into their own inferiority.”

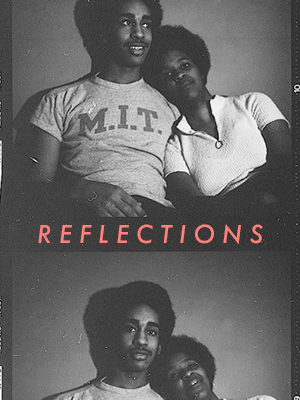

So when I came to MIT, contrary to some of the experiences I’ve heard at one of the reunions, I really found that the other students were terrific. They were terrific kids, terrific people, and open and warm. They accepted me better than I was able to accept myself. Then, not living at home anymore, having to live amongst them in fairly close proximity and seeing what they looked like and smelled like and acted like when they were themselves and so on, I think I actually got a lot more self-confidence after I came to that environment than I had before I came. There were some areas in the Institute where Shirley and I were viewed through racist eyes and we were tagged the Tweedle Dumb twins and derogatory terms like that. I think people in Admissions who do all of the calculations on predicting success and who should they admit and so on, I was insulated from. I never had an occasion to go there. I was insulated from that, thank goodness, because that might have hurt my feelings at the time.

But MIT was everything I had expected and hoped for from that little brochure, by the way. I made a number of friends amongst the other students in the dorm and in my classes. Also, there were a lot of international students and for the first time I met a lot of students from the Continent, from various countries on the Continent. For me, that was a very broadening experience. For me, Africans who were from Africa and who had not lost their roots and who had their sense of identity and culture and heritage intact, I really liked that. I had a lot more sense of self-confidence after experiencing that, despite the fact that we were seven African-Americans out of nine hundred in my freshman class. People came from a lot of different places. It was sort of my first experience at a world view of things and multicultural diversity. Then there is a certain sense of giving people credit for having an intellect and being capable. Some students don’t succeed, but it’s often because of the emotional problems that they’re going through and not so much because they’re not expected to because of their racial background. In that sense, I actually grew at MIT compared to where I came from.

You talked about seven students. I guess it’s so hard for you not to know each other.

Well, it was hard. I didn’t get to know some of them very well. I had a work-study job. My work-study job was working in the libraries. I started working in the library my senior year in high school before school. When I came to MIT, my work-study job was working in Hayden Library at the circulation desk. We also had a little book of all the freshmen and I think there were upperclassmen in it. I had nothing better to do than kind of flip through the pages and look for the brown faces. People would come through and there were upperclassmen or graduate students and I’d say, “Hmmm.” I would see their names when they signed out the books. So, I got to know a few people who were library studiers. I mentioned Alan because he lived a couple of dorms over from us. Eddie Rhodes was a DJ on the radio station. He played the jazz program and I was a jazz enthusiast, so I loved listening to him. I would see him occasionally on campus, but I don’t recall having any classes with him. There was Danny Alexis. I think we tried studying together from time to time. I think he was in the biological and nutrition sciences major, so I saw him a bit. The other couple of fellows I can’t remember right now. I think one lived across the river in a dorm and was in engineering or something. I didn’t see them as often and didn’t get to know them very well.

When did you decide what you would actually major in at MIT?

Well, my freshman year I was overwhelmed with the workload. I signed up for a lot of activities and was taking physical education when it wasn’t required. It was a disaster because they did gymnastics, and women reach their peak when they’re about 14 in gymnastics. I had two square meals a day and gained 10 pounds that first semester, and I couldn’t cope with that physical demand of gymnastics in an all-male class.

I joined a lot of other things. Because I was strong in math, I didn’t study my math. I kind of coasted on what I had when I came here. That was my fatal flaw, because I fell in love with physics. I really, really thoroughly enjoyed the physics and without the math as a background — that is the fundamental basis to do that — I couldn’t do well in it. I did badly in my physics class. I had Philip Morrison as my recitation instructor. He was like the legend, and he was from New Jersey. I was so in awe of all of that, and he was a great, gifted, and spirited instructor. I didn’t know what was going on, but I just liked listening to his lecture. I thought I wanted to do physics, but I didn’t do well — didn’t do that math, let that math coast while I was trying to adjust to other things. I had to make a lot of adjustments and adaptations to the new work schedule during that freshman year. I never had to work so hard and so long. As a result of that, I didn’t do well in second semester freshman physics and had to repeat that course. That pretty much took me out of the physics running. I was able to regroup and had a little setback with organic chemistry, but got through that and ended up as a biology major and well on my way to being in a position to take up medicine later. That’s how I ended up in biology.

So you basically maintained your interest in the idea of medicine from pre-college days.

Well, I still wasn’t looking toward medicine then. I was looking toward maybe biochemistry. I was actually shocked when I found out senior year that the vast majority of my Course VII major classmates were applying to medical school. I said, “Oh, they’re not doing true science or research or whatever. They’re going into medicine.” I was surprised by that. I went to graduate school in biology and then took a year off to go work at the Malcolm X Liberation University in Durham-Greensboro, North Carolina.

At that point, after a couple years of graduate experience, that’s when I decided that maybe the laboratory wasn’t for me — that I was more of a people person, that I needed to find some application of my science background that would allow me to serve the black community more directly. I said, “Oh, I don’t believe this — now you’re going back to exactly what you said you wouldn’t do when you were in high school.” So that’s when I decided to look toward medical school. When I went back after my year off, I applied to medical school. When I got in, I left graduate school. I never got a graduate degree. I left graduate school to go to medical school.

I see. So really when you were going through MIT, you weren’t sure about where you were going to land.

Right.

I heard that quite frequently students would mistake you for Shirley, and Shirley for you.

Isn’t that amazing? We didn’t think we looked anything alike. She was very, very petite and I was a little chunky. We were both kind of the same height, but other than that, I didn’t think we looked anything alike. But you know, like I said, we were called the Tweedle Dumb twins at one point. After maybe freshman year, when you take so many courses together and then we sort of ended up going in different major areas and taking a different complement of courses, it wasn’t a problem. The women in the dorm certainly knew who we were after one year. After that, we wouldn’t really have that many classes together, so it didn’t overwhelm us. It was sort of amusing to us.

Did you recall actually strong discrimination, racism so blatantly?

At MIT, no. In graduate school, yes. That’s when I first came into contact with that.

Let me have you stick with the undergraduate for a couple more minutes and then we’ll go on to your graduate program. On the undergraduate level, that was a very crucial period. Are there any faculty members or mentors who stood out for you during that period?

“Having been a strong student in elementary and high school and then getting an F for the first time in my life, boy, I really felt like dirt. I was really, really upset. “

I think the person who had the biggest impact on me was my freshman advisor. His name was Ned Holt. He was a faculty person in the biology section. He had us all to the house, the whole group of us in his advisory group. I got to meet his family and his kids and so on. I remember going to him when I knew I failed that electricity and magnetism final. I remember going to him after that and trying to figure out what to do. Having been a strong student in elementary and high school and then getting an F for the first time in my life, boy, I really felt like dirt. I was really, really upset.

This was in your freshman year.

Yes. I didn’t know what I was going to do and he was very supportive. Also, during the first semester when I saw how much I needed to adapt, I dropped all of my activities and all of my clubs and all of the other things I was in. I even dropped cheerleading. I kind of knuckled down and got into a more rigorous schedule, organized my time a lot better. He talked me through all of that. Then when I did get ready to apply to graduate school, I didn’t think about going to medical school. It was kind of a surprise how many other students in my class were going to medical school. I didn’t have enough confidence in myself to think that I would get in. He recommended Wesleyan, which was the undergraduate school he had come from. He was still in touch with some of the faculty there and he wrote me a nice letter of recommendation.

This is Wesleyan University.

This is Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. That’s how I ended up at Wesleyan for grad school. Dr. Holt pointed me in that direction and said, “They would be pleased to have you there,” that sort of thing. The sad thing is that he did pass away prematurely.

That’s why you don’t know him.

I think he died while I was in grad school, not long after I left MIT. I don’t recall what it was he passed from, but it was definitely a premature death. I found out about it from the paper and newsletters and so on.

So he was a major force in terms of supporting you.

He was just very nurturing, kind of a nurturing father figure. He talked me through some difficult times and also helped me move to grad school.

When you look at graduate school, you went to Wesleyan and you were focusing on what subject?

Biochemistry.

Did you have any idea what you would do with biochemistry at that time?

After I was in college, each summer I went home to Peoria and I worked in a lab. It was called the Northern Utilization Research and Development Division of the Department of Agriculture. They had a laboratory in my hometown. The first summer after college I had gone there and gotten one of their summer jobs. So, I worked in the lab mostly doing microbiology and some other things — some biochemistry, but it was basically a microbiology section of the lab. I felt pretty much at home in the lab working there. For a short time, I had one work-study job doing solutions for the biology lab at the biology building. I just figured I would do research and that sort of thing, something in that area. Even after people in my class went on and did Ph.D’s, the Ph.D’s were having a hard time finding jobs. The research money and funds were drying up and, except for those who were in academia, it was getting very difficult. That was part of the reason why I switched to medicine, but not the only reason.

Wesleyan did not have a medical school. You stayed there how long?

I guess it was over the course of three years. I went there for two years, took a year off, and went back for one year during which I became pre-med. I finished the year, but I didn’t finish the requirements for the degree. I found out that they were keeping people there seven years to get their degree. It was a new program. I think they didn’t have a lot of self-confidence about their ability to produce Ph.D’s.

I wasn’t too happy with one of the biochemistry instructors’ handling of my lab grade. I had come there and I had had all of the biochemistry labs at MIT, you know, that we did as graduate students. I guess he thought I was a little too carefree and jolly or lackadaisical in the laboratory, but I had had it all and I was showing the other students how to isolate the DNA and extract it and so on and get the things in. I always got A’s on the lab write-ups and he gave me a B-minus or something like that in the course. I said,“I don’t understand how you came up with this grade.” He had averaged my lab report grades with something he called attitude, for which he had given me a C. He hadn’t discussed it with me, hadn’t told us there was such a thing. Then he averaged this C for attitude in with the A’s and came up with a B-minus. I said, “Uh-huh, yeah, I’ve got your number. I will remember this.” I don’t understand that, how he just created this subjective grade because he just couldn’t give me that A.

So that’s why I said I ran into racism in graduate school. That was one example, so I didn’t really feel bad. I had some other wonderful experiences there in terms of African-American studies and African dance. They had a wonderful world music program and we were very active. It was a very active time in terms of students taking over buildings on campus and all sorts of things. So it was an exciting time to be there.

That was around what, ’69?

’69 to ’70.

They had an African house on campus at that time, too.

Yes, that’s right — Afro-American House.

Did you have any experience with that particular house?

That was sort of unusual on campus. The front was like the offices for the academic program and in the back was a black dormitory. I don’t think they had frats and a black sorority or anything. It was also the time when Wesleyan was going co-ed. They had some of their first co-ed students, and I think I was a counselor for the orientation program a couple of summers. It was really an exciting time. It was a liberal arts college, quite different from MIT. I was a teaching assistant for some of the science classes as a graduate student, so I met some of the undergraduates who were pre-med. There were some very talented fellows who were there too.

That’s a very good school and continues to be a very good school. Our son went there, so I’m very familiar with the school. I was very impressed with it, and still am. That house still exists and they still use it the same way, for the most part, as I understand. That was about four years ago. At the “college night” at my daughter’s high school, I always go to the Wesleyan table and think, “Just say hello to whoever is there.” The fellow who was there last was a Latino guy and he was saying that Fay Boulware had dropped by recently. She was a faculty person for a while and her son had gone to school during that time.

So you left there and went where?

When I left Wesleyan, that’s when I went to New Jersey for medical school.

Now, who played a big role other than yourself to make that kind of move?

Well, as I mentioned, I took a year off and I went to the Malcolm X Liberation University. It started in Durham basically as an offshoot of the Duke University Black Student Organization. All of this happened after 1968, when Martin Luther King was assassinated. At MIT also, Shirley and I got together and founded the Black Students Union as a response to Martin Luther King’s assassination. We wanted to form some kind of group for black students on campus, so we could get together and do positive things.

I’m glad you mentioned that.

Yes. Just to backtrack, we forget about the kind of militancy I was getting into at MIT. I did venture off campus a few times and I remember going into Roxbury to hear LeRoi Jones give a presentation that was sort of poetry with a political message, kind of a dramatic presentation, getting the audience involved in it. I remember the line he always said about how they started picking up the black station on the radio as they drove up from Newark, and he says,“Ah, we’re approaching civilization.” They closed all the doors and they didn’t want whites in the room.

Another time I was over in Roxbury somewhere listening to Stokely Carmichael speak while I was a student. That might have been about the time I got my afro. It was my senior year when Martin Luther King was assassinated. Malcolm had been killed my freshman year at MIT. That was in 1965.Then Martin was killed in ’68.That was all during my college years. In between, my first trip to New York City was with the big anti-war rally, probably in 1967. We had a whole contingent of buses from New England. It was my first experience demonstrating in the streets, wall-to-wall people filling the UN Plaza. That was part of that whole anti-war era. Much of it got me a little bit politicized in that era. Vietnam for the Vietnamese and, later on, South Africa for the South Africans.

In any case, I left MIT right after all of that. I went to Wesleyan and they too were developing a black student organization. They had the Afro-American Institute already. We took over a build.ing for a day and a half or so, and made certain demands that the administration capitulated on and gained some understanding of Ujumaa, we called it, the student organization on campus. Some of the students from Wesleyan had been down to Malcolm X Liberation University and had told us about it. That’s who told me and that’s how I found about it, that it existed. Another student from Holyoke College who was graduating a year behind me in school, a biology major, she was also going there. So we decided to go down there.

I took a year off from school, a leave of absence. I got funding to do that. It was a very interesting experience. As I mentioned, we had kind of a curriculum. We were trying to develop a school to teach skills to the community. We were trying to teach biology and chemistry to the students. A pharmacist came in and he was teaching pharmacy. I really got interested in that, the chemical applications of these pharmaceutical drugs in certain medical conditions and so on. The pharmacist was very, very nice and very supportive.

Where did he come from?

He was a pharmacist at a local pharmacy in Greensboro.

That experience was very, very invaluable to you in that period.

It was also my first experience in the South, North Carolina.

Exactly. When you look at your career, you had been in Illinois, Boston, Middletown, then North Carolina. Give some kind of assessment of the contrast between those places.

North Carolina was the first time I had been someplace where I could go all day and all night and just see black folks. You go to the K-Mart and you’d be checking out behind somebody who sounded just like Gomer Pyle. It was like, “I can’t believe it. He sounded just like Gomer Pyle.” Basically, you just function all day long and, unless you went downtown, you really didn’t come into contact with any whites. I said, “Now I see what they’re talking about.” It was really interesting.

It’s very interesting, because I come from North Carolina, so I know during that period of time exactly what you’re talking about. Did I hear you say that this pharmacist came down and talked about all of the different kinds of chemicals and formulations and all of that? Did that kind of spur you on to not only go in further with medicine, but actually to sort of specialize in something?

It didn’t tell me what to specialize in. It was sort of like when I was at MIT. I didn’t know what I was going to do with what I was learning there. Similarly, when I was in medical school I couldn’t figure out what I should go into at all and I kind of fell into that. Otisa Barr was the student from Holyoke who was with us. We were the students, the pharmacist was the teacher. We were taking a pharmacy class. I really enjoyed it and I did well enough, you know. I think the pharmacist was very impressed. In fact, Otisa and I are both physicians. She’s a pediatrician. She’s back in Washington, DC, which is her home town. I did adult medicine.

Again, I had a hard time trying to decide which specialty area of medicine to go into because I liked everything. As it turns out, the area that I applied for was one you had to apply for a year earlier than the others. I didn’t realize it was a more competitive and lucrative field, gastroenterology. I didn’t know that. I just applied because I knew I had to apply a year earlier and, when I got in, I went into it. We had some black faculty members at my school. A world-famous liver specialist named Carroll Moton Leevy, at the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, was the department chairman whom I trained under. There were several others. Dr. Frank Smith and other people were in the liver section. We saw a lot of liver disease in Newark — a lot of liver disease, various kinds. I was always fascinated by that. I moved to the gastroenterology division. I applied, I was accepted, and that’s how I ended up in gastroenterology. I haven’t regretted it. I really enjoy the field.

I noticed that you’ve actually sort of stayed in that arena too — that is, in the New Jersey area.

That’s not unusual. Apparently, one-third of people end up practicing in the vicinity where they’re trained. Even when I came to MIT, I never met a person from New Jersey I didn’t like. I liked the people. They were so friendly and open and honest and frank, just fun people. New Jersey is an interesting place. If you’re not from New Jersey, you don’t mind. People from New Jersey, a lot of them try to get away from New Jersey. But I was away from some place, away from Peoria and the negative memories I had about the racism. When I go back it’s like going backwards in time, not just crossing the miles. Culturally, once I came East it was very difficult to go back. It’s kind of a culturally less stimulating area, politically less stimulating. In the urban areas, you have to deal with a lot of other nonsense, violence and crime and so on. But you have a lot of gifted, talented, accomplished black professionals you can get to meet and interact with, and that makes up for it.

So I go back to see my folks, but I haven’t yet decided to go back there to live. New Jersey will do. Then Shirley ended up in New Jersey, too.

That’s amazing, that both of you ended up in New Jersey. You’re in a field in medicine that clearly is a very important one, and I only know one other person who is in that field. He is at Hampton University. His name is George J. Brown. He just became a general in the army. Well actually, he was at Walter Reed Hospital. He was the physician for Chadwick. Remember the black Air Force general who died a few years back? I think his name was James Chadwick. Anyway, I understand that the training is very, very intense. Is that right?

Well, I must say that after doing biochemistry at MIT in the very beginning, I was broken in. Then, having to do a lot of those courses again in grad school before I switched to medical school, by the time I got to medical school it was the third time around for me. I got honors and I would always get the top scores in the class on the biochemistry test. Everybody thought it was so terrific. But this was the third time around for me. Again, as I mentioned, they had a very aggressive recruitment program, they had some very talented people. I think, even still, my particular class had the largest number of minority students of any class before or after. They did a good job of recruiting. They had a number of people who had done other things before they came to medical school. A mechanical engineer — he had been at MIT for a while. He was sent by his company for some training. A microbiologist and some other Ph.D’s were in the class, and some other very talented people who had done some other things who weren’t just out of college. We had quite a fascinating group and we were in a summer program together before we started. I had a terrific time in medical school. I enjoyed it thoroughly. I really thought it was great fun. I had to work hard once we got to internship, but I thoroughly enjoyed it. I was definitely in my element when I was in medical school. I don’t regret it at all, and really found that it was the kind of field where I could be in contact with people, felt I was doing something.

“The whole time I was at MIT I was on a constant guilt trip because I felt torn between leaving the campus and going out into the black community.”

There’s another thing I want to talk about. The whole time I was at MIT I was on a constant guilt trip because I felt torn between leaving the campus and going out into the black community. What I wanted to do I wasn’t sure, but I wanted to be involved, I wanted to be in touch, I wanted to be of service, I wanted to find out what was happening politically. I was always torn between getting involved with those things and trying to do my work, which was clearly always challenging. I remember being down for the reunion a few years back and having one of the other people mention that he was counseling a student. The student wanted to be involved in the community, but he didn’t quite know what to do. He said, “The best thing you can do for yourself and for your people right now is do a good job in these courses.” It’s true, but it’s still very difficult to constantly be torn between wanting to take your limited energies and resources and talents, to defer that kind of involvement to immerse yourself in the black community, while you’re trying to stay in your dorm and stay in the library and do your studies and work in the lab — whatever — and constantly be isolated from that source of energy and your base. Finally ending up in the medical field gives me the best of both worlds because I’m in contact with people and I get immediate gratification when I’m able to do something to help someone. The vast majority of my patients are black — African-American, Latino-American, and a small number are of Caucasian extraction. I think that worked out well for me.

Well, you know it’s really important that you said that. I couldn’t help but think about a young lady, just this year. I would love for her to hear your comments. She is an awfully bright young lady from Brooklyn. Her father, I think, is black, and her mother is Asian. She came and talked about exactly what you were just saying. After spending a year at MIT having to work so hard and concentrate just on her work, she was concerned that she was not going to make a commitment to her community where she felt they needed so much from her. This education in this way — all of the science and all of the math, physics, chemistry — didn’t quite click with her. She was torn. We have begun to try to get her involved in some other things along with doing her work, but she’s made the same identical comment that you just made. When you’re going through it, evidently it’s not easy to just say, “Well, I know this will eventually make a difference.” That’s what I hear you saying.

It’s not really even enough. I understood what the person was telling that student about stressing that you do well in this subject. That’s true, because you’re generating that foundation for the future, you’re generating your own academic record that’s going to be used to limit or open up opportunities for you later. But if there were some way that people could concentrate on their schoolwork and then have some time where they felt they were in touch with each other doing some collective political analysis of things on campus and working for some cause or having a project that they could put some effort into on the weekend or have a summer job that would allow them to do that, I think that would help round them out a little better and give them a little bit more of a purpose while they’re meeting other needs at the same time.

When you really look back and you do a summary and an analysis of your perspective of the MIT experience, indicate whether that perspective evolved over the years and over time. At the present time, when you look back on it, how do you come down on that experience in terms of the value?

Well, I know that any school or college is always trying to figure out what they want to provide their graduates with, and you can’t always keep up with the latest work environment or demands. What I understood from them was that they wanted to teach us how to approach a new experience, how to approach a new problem. I think they did that for me. I definitely had to be adaptable during those years. Every year I got better at it and every year the challenge was more difficult, so I continued to have to get better at it. By the time I was finished, by the time I graduated, I really think I was at my academic peak in terms of being able to handle whatever you threw at me. At that time, I had certain basic sciences and my life sciences and I had done some art history, I had done some photography, I had done a foreign language — a new foreign language. I really felt like I could have handled just about anything you threw at me at that point. I think they did that for me, to give me enough fundamental skills that are current enough in the field that I could go out and just really adapt to things. I’ve had to adapt a lot more, many more times during my life, and I’m adapting even now — trying to adjust to new demands in my field and trying to rise to the moment. I’m getting new skills and new credentials even now, at age fifty. I think that’s what I came away with.

Based on your experience at MIT and your experience and rise so far in your career, is there any advice you might offer to any other black students, the young Jennifers coming through, beginning to come through MIT?

Well, I would say take advantage of and sample all the different things that are available for you to experience or see or learn. Be a little bit introspective and see what it is you think you would enjoy doing. Keep an open mind.

Do you want to talk a little bit about some of the support services?

Yes, because those were really key to my MIT memories. In particular, I remember they had a program for the incoming freshman women. They had an upper-class person sort of be like your sister. Edie Goldenberg was my sophomore sister. I don’t remember what Edie majored in. I won’t even venture to guess right now, but she was my upper-class sister and she was also in the dorm when we came in our freshman year. I remember very importantly our two tutors, our two dorm tutors. Our physics dorm tutor was Margaret MacVicar and our math tutor was Harriet Fell. I don’t know if you know Harriet. She was from New York City. She was the first person I ever heard describing a curve as “getting bitchy.” She said, “Don’t worry about that. After that, it gets bitchy.” I said,“Oh my goodness. We’re in college and you’re using these curse words. Oh my goodness.” She was funny, but she got right down to the nitty-gritty.

That was very critical, coming from a public high school and meeting students who had a lot of the same material at the same depth in high school, having the dorm tutors help us out, and having a whole lot of other company and having them take us by the hand and really go over some basics with us and being there and being available. I know Scottie MacVicar went on to be a very important figure in the Institute, and she also has passed on.

Yes, she has.

She was always there for support for those of us who had problems with our physics courses.

It sounds just like her. As you know, there’s a fellowship, a professorship named after her for outstanding teaching, which is very appropriate.

Very appropriate. I lived in McCormick Hall my freshman year. Sophomore year, we kind of outgrew McCormick. That was before their next tower, I guess, would open. They put a few of us up in what had been a dean’s home on Memorial Drive — Moore House, it was called. I think later on it became a frat, but that year they had, I forget, about fourteen or so women there. I had roommates who weren’t in my class, but they were chemistry majors. I remember them being very helpful to me when I had to drop organic chemistry and still had my lab course. At Moore House, the students were very supportive also and helped me get through chemistry. Then my third year on campus, I lived in Westgate. Again, we were outgrowing the facilities and they gave us a floor in Westgate. My roommate was Natalie Weiss. What a phenomenal individual Natalie was. From Natalie I learned how to be disciplined. Natalie was a very disciplined person. Some of my other classmates who did well academically always made sure they got eight hours of sleep, but Natalie would stay up all night if she had to. She would get her work done.

Did that rub off on you?

That definitely was a positive role model for me. I said, “Well, I’m just going to do what Natalie does. I’m going to stick with it. I’m going to keep at it until I get it done.” Natalie graduated after her third year. She was so organized. She was looking forward to enjoying her senior year, but her parents said, “Oh no. We’re not paying tuition for you to go just for fun.” She did so well that she met all of the requirements for graduation after three years.

Was she black or white?

She was European, Jewish extraction. She was from Maryland and her father, I think, was a scientist. I forget what her mother did.

Did you ever talk to her later?

Yes. Natalie had to leave, she had to graduate. Her parents said, “You can’t stay here and just play the viola now.” She went to the University of Chicago, I believe, did a Ph.D. there. She said she was never going to get married, but the next time I met her was in New Jersey with her husband whom she met in Chicago. She had two little children, so we used to get together on the weekends and take the kids to the zoo. I had a daughter by then. I got together with her until they both got their degrees. That’s when I knew how difficult it was for Ph.D’s to find work. They both managed to get faculty appointments, I believe, at Duke University in North Carolina. They left New Jersey for there. I think her husband’s parents were from New Jersey and that’s why they settled out there. We lived in the same town in New Jersey for a while. Those were some of my really major supports in terms of helping me develop the academic discipline I needed to tackle tough courses.

What about the offices during your time, like Student Affairs and other kinds of offices that really were there for students? Do you recall any major support from that?

I remember the major support I got from that financial aid office. I remember picking up my check from that work-study program. Also, the Student Center opened up the year before I graduated. My senior year I worked at the twenty-four-hour-a-day reading room. That was where I was working. I really enjoyed that. We were at a great location on campus because we were near the auditorium where a lot of the things are held — at Kresge and the Student Center, where a lot of activities were held. Of course, my fourth year I lived off-campus. I had my own apartment with one classmate and another woman who was working.

How tough is it for a woman to be in such a demanding field?

My daughter doesn’t like it because it takes a lot of time away from her. Now she’s sixteen so she thinks she’s grown and she doesn’t really need me around anymore, but when she was in elementary school, she resented the fact that I had to be away so often. I had at one point when I finished my training thought I would have been very happy working for something like an HMO, where I had a little more scheduled hours and scheduled times off. When you’re off, you’re really off, then take calls in turn so as to have other time off to spend. I didn’t have that opportunity when I moved into private practice. I’m still in private practice, but I understand that the environment in which we work is changing and that’s an unstable situation right now — the changes in the health-care industry, the move toward integrated networks and managed care system. That’s what they’re saying, so I’m not sure exactly where I’ll end up. But we all know that we’re not going to continue to do what we’re doing for very much longer, the way we do it.

That would have a tremendous impact on private practice, I would assume.

Right. We’re said to be an obsolete entity, but as long as I can continue to do what I am doing, I will continue to do so. I know that the environment is changing. The market forces are making us adjust.

Is it really changing that rapidly for our people, particularly in black and Hispanic communities?

Yes. The people who are on state and federal health-care systems are being routed into HMO’s now. So we have to be within the appropriate HMO network even to continue to care for the majority of the people who are on Medicaid and Medicare. The people who are on the commercial side are becoming more and more HMO-affiliated as opposed to just getting a guaranteed plan. Those are becoming unaffordable, so they go to an HMO system, of course, and make it more affordable. Consequently, you’re bound to a certain provider network. If you’re not in that provider network, you basically have to wave bye-bye to your patients whom you’ve been treating for ten, fifteen years. People are trying to adjust. It’s hard to make strategic moves when you don’t understand the system. We’re floundering and we’re trying to understand what’s going on, what’s happening to us, and trying to make decisions as they come up and trying to adjust and adapt. It’s interesting and I’m pretty discouraged about the whole way things are going in that area. I have made the decision to try and stay in the field, another adaptation in the making.

That sounds like the typical MIT way.

Yes, right.

Well, are there any other comments you would like to make?

Yes, I have a bone to pick. Social life — let’s deal with that social life aspect of things. I hope that’s better these days.

Well, it’s interesting. I have about three black young women who worked in my office, sort of connected with a class they took. Just this week, the three of them were talking about social life. I didn’t get the total gist of it, but it appeared that they were not pleased with it.

Right, that was a problem. There were just a few other blacks in the class and we didn’t really have any organization through which we got together and did things socially, to fraternize or get into the social aspect of things. “Fellowship” is the word I wanted. Shirley and Linda Sharpe had gotten involved in the Delta Sigma Theta sorority and brought me along with them for some of their occasions. It was positive to see some of the people they met through that, which was an all-Boston, all-citywide kind of organization. That was also good because you went to other campuses and met students from other schools. Shirley, having been from DC, had some other schoolmates from her high school who were in the area. I remember Veta from BU coming over from time to time, and then being able to meet people through that mecha.nism. We were sort of living in isolation, and the few black fellows who were around were more interested in Caucasian women.

That was sort of like a negative aspect of my experience. You know, “What about me? I’m here.” I dated Caucasian guys too, but you have to deal with major cross-cultural, social kinds of chasms, you know? It’s one thing to be good buddies and good friends, but when you’re supposed to be dating it’s a little bit more. There are hurdles. That wasn’t too good. I was spoiled. What’s the ratio of men to women? I mean, what was it in those days? About fifteen to one?

Well, that’s true.

So I guess I had more dates with different people than I did with one person. I did socialize in African circles and that was interesting — the music and the dance and everything. I always liked music and dance. Again, there was a big cultural difference and of course most of them are very accomplished, bright folks, but there are a few cultural gaps to deal with there.

That’s an excellent issue that I know is still very much alive. I don’t know what black women would actually say about what’s going on now, but it certainly is an issue because I’ve heard it enough. I think the ratio now is probably more close to being even.

Amongst the minority students?

Yes, still probably a slight edge toward the men. I must say, just from a distance, on campus I do see more couples, black couples. Again,I would not dare say what the case is because I don’t see enough, and the key would be what black women would say.

I really feel that I am capable of having the cross-cultural relationship. That’s not the problem. But as I mentioned, at that young, naive stage of my life, being very vulnerable, and having a lot of insecurities and lack of self-confidence, it didn’t help in that area. I got over that kind of thing that because I was Negro or black that I should be inferior. I got over that, but then the whole coming through adolescence and into your social life and then being ready to move on to a real relationship — that did not happen.

That’s a very important topic, I think, that I’m going to make sure I talk about more with all of you in the different periods of time. It’s something that even if people don’t talk about it, it’s on their minds.

Right, exactly. We were around enough to see some people — other students, not necessarily black students — get into relationships and get into marriage. Some of them, before our eyes, broke up. Some of them married. Then other people who we were used to seeing as a couple we would find out that they broke up. That was kind of discouraging. I think that there was a lot lacking in terms of some medium through which the black students could have fellowship. Even if you’re not interested in someone romantically, you could use it to get together and do things together and fraternize.

Would that be one of the things that you would actually encourage to happen on our campus? Describe what you would recommend more of.

Well, I will tell you something that I enjoyed thoroughly when I came up for Alumni Week a few years ago. I really thought that the program sponsored by the black student organization was the most happening thing on campus that day. They had some fantastic forum going on — about blacks in science through the ages, with some really outstanding panelists. Mae Jemison, the first African-American astronaut, and Ron McNair’s wife, Cheryl, and some other people were there that day. It was absolutely fantastic.

Who sponsored that, do you recall?

The black student organization, BAMIT.

Oh, BAMIT sponsored it. That’s a great young man, Darian Hendricks, who’s doing excellent work.

Yes. I really thought that was good, and that it bridged the gap between the alumni and the current undergraduates who were around. Also, at that particular forum I met a group of high school students from a science high school that was just started. I said, “Well, where is your high school?” I ran into one of the students and he said, “It’s in Newark, New Jersey.” I said, “Oh, that high school, I read about you.” I met the principal that day and my daughter was finishing eighth grade. She applied and went to that school the next year. Mom was her link to find out about this high school, science high school. It’s called Chad Science Academy.

That was a nice bridge, that sort of event, and whatever things they have during the school year that they might do periodically, regularly, social and otherwise. I’m not sure what their regular academic year schedule is like, or the events.

I think they offer things all year, but in general the undergraduate students — particularly the National Society of Black Engineers — I’ve heard that they have one of the most provocative programs or student groups in the country. And the MIT group outshines them. I mean, they do an exceedingly good job. They have excellent programs, outstanding leadership, people are very serious about who is elected as president. They really, over the years, have been just fantastic. I think the BSU, the Black Students’ Union, depending on the leadership, sort of goes up and down. But the National Society of Black Engineers is always very good.

I must say that it’s a pleasure, particularly when one looks at the significance of your contribution at MIT. As one of the first black, African-American women to graduate from MIT, you will definitely be noted in history.