How Nintendo Bled Atari Games to Death

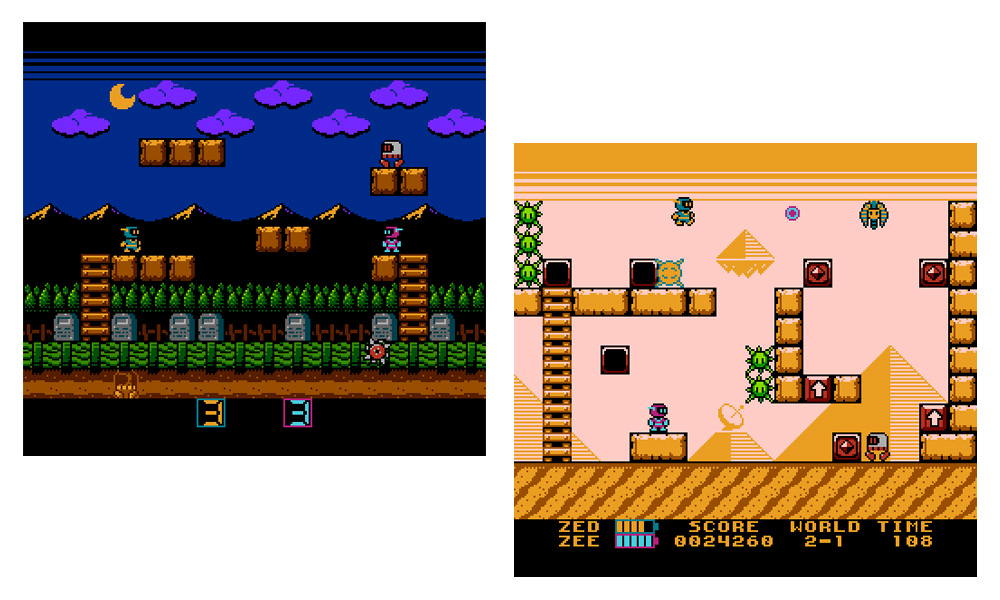

In July 2024, a new company called Tengen Games released its first game, “Zed and Zee,” for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES). The surprising part of this story is not the release of a new “homebrew” game for a system released in 1985 — hobbyist computing has been visible since at least the 1970s — but that Tengen and its parent company, Atari Games, had disappeared 30 years ago after being crushed in court by Nintendo for doing exactly the same thing: manufacturing unauthorized cartridges for the NES.

This story isn’t just a curiosity — it highlights how the gaming industry, like many creative fields, is defined as much by legal and business decisions as by artistic vision. Behind every major shift, there’s a dance between engineers, lawyers, and business leaders, visible only to a few insiders. Nintendo’s lawyers, more than Mario, made Nintendo. Atari’s lawyers, more than ET — notoriously the worst game of all time — sealed its downfall.

To illustrate these points, let’s take a walk down memory lane with Atari and Nintendo. Press Rewind on that analog tape deck. The year is 1979. Atari is at the peak of its commercial success, but the mojo is gone. The freewheeling culture has been replaced by the Brioni suits and New York secretaries of new owner Warner. The existing industrial arrangement at the time was that of a bundled console-plus-cartridge business model, where the console manufacturer (say, Atari with its VCS/2600) sold the console at a loss and cross-subsidized it with the money made on cartridges sold with a huge profit margin.

Nintendo’s lawyers, more than Mario, made Nintendo. Atari’s lawyers, more than ET, sealed its downfall.

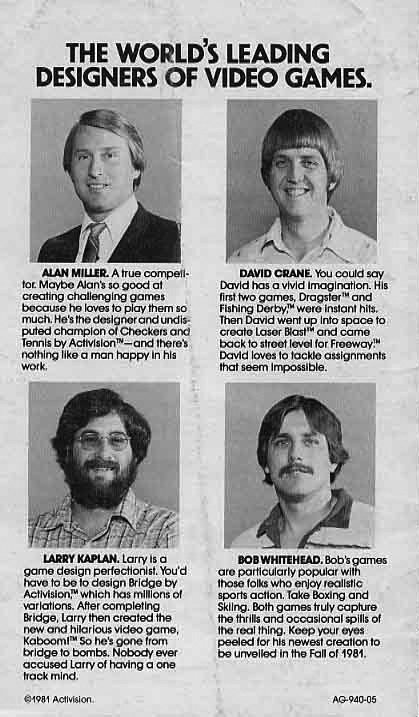

Except, the game designers were paid a flat salary, not royalties, unlike the rock stars in Warner’s stable. In late 1979, four defecting Atari designers and one music industry executive disrupted the video game console business model by aligning it with the recording industry’s: Hardware would be just hardware, and content would now be supplied by third-party content providers. Activision was formed, with a little business and legal help from the Sistine Chapel of Silicon Valley law firms, Wilson Sonsini Goodrich & Rosati.

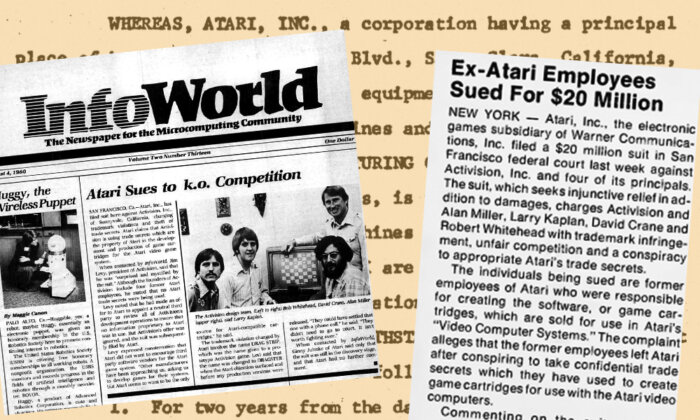

Atari sued Activision, slapping them with any legal argument Warner could come up with — theft of trade secrets, copyright infringement, trademark infringement, patent infringement — but nothing stuck. Activision’s business vision and legal team beat Atari’s. The floodgates of third-party game production opened, and the model remains the paradigm today.

Soon, however, the game market became saturated. Too many players for too small (at a time) a market meant it became impossible for most developers to scale and recoup their costs. Quality also dwindled, leading to customer dissatisfaction. To differentiate, some publishers released what Videogaming & Computer Illustrated described as “enough to send the most liberal sexual enthusiast staring at his/her shoes in abashment,” leading to public outcry and a bad rep for the industry as a whole. In late 1983, the video game market crashed, leading to the collapse of both Atari and Activision.

Enter NES. In 1985, Nintendo introduced the NES in North America. Three years later, competitor Sega introduced the Genesis (also known as the Mega Drive). Both companies had learned from the crash and took steps to prevent third-party developers from releasing unapproved games. Where Atari’s legal arguments had failed, they turned to an engineering strategy: A proprietary lock-out chip would be inserted in the console. A lock-out mechanism is an ensemble of software code that is burnt into two special-purpose chips. One is placed inside the console. That piece of software, embedded in silicon, looks for another piece of software, an unlocking key, which is itself burnt into another special-purpose chip added to the game cartridge. When a game cartridge that contains the key is inserted into the console, the key and the lock shake hands, and the key opens the lock.

The source code of the software embedded in both chips is kept secret by the console manufacturer. To keep the keys a trade secret, the console company burns them into the chips in a form that is understandable by machines but not by humans. To ensure even further protection of these secrets, both Nintendo and Sega manufactured the approved third-party game cartridges themselves, before selling them to the licensees who in turn distributed them through toy and computer stores. If I wanted to make a game for the NES, assuming I was one of the happy few to be vetted, I would deliver my game software code to Nintendo, who would add the secret key to it, burn the whole thing on a cartridge bearing my name, and hand that cartridge to me so I could then sell it through my own distribution circuit. Not efficient, but effective, as far as keeping the source code of the lock-out system a secret.

Many in the industry took umbrage with this model, in particular because it enabled the console manufacturers to impose what developers considered unfair business terms. Nintendo, in particular, was known to be a bully, and its behavior even led to anti-trust investigations by the U.S. government. But as every thief knows, every lock can be unlocked without the official key — it’s just a matter of time. In this case, that time was 1989.

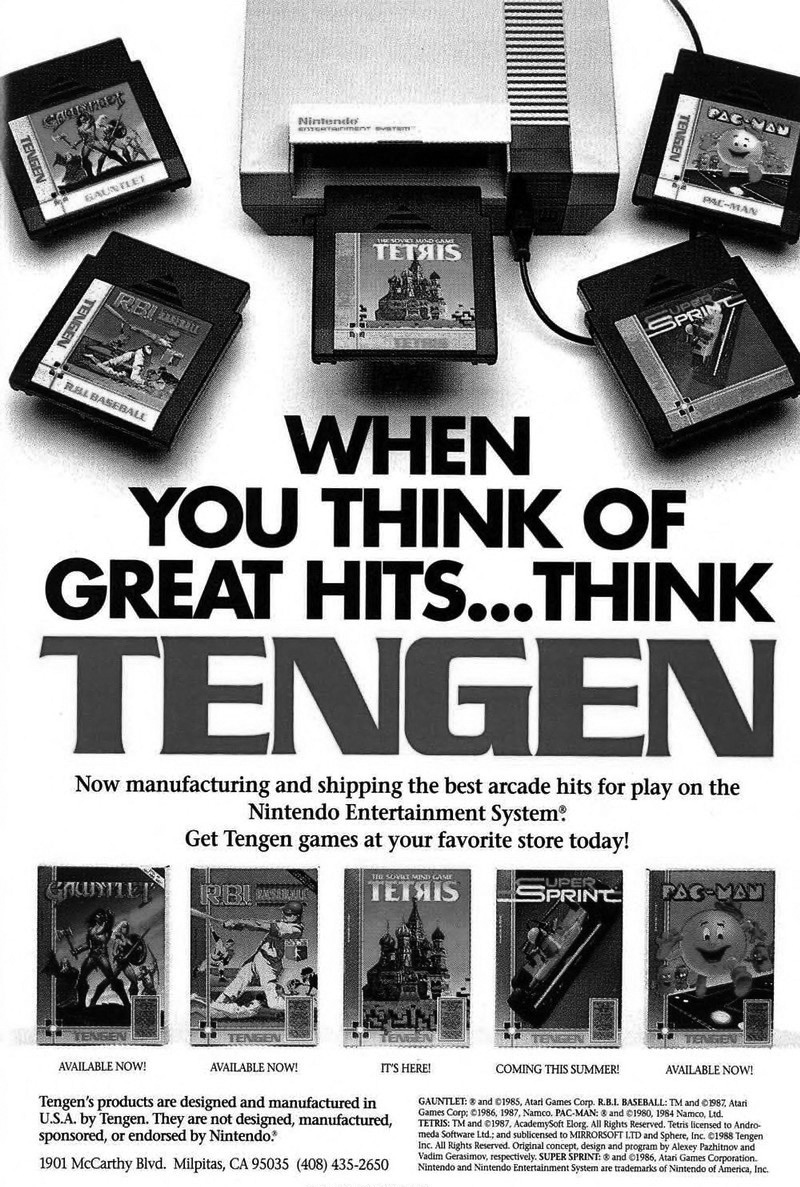

The original Atari had been split after the crash, and Atari Games, doing business as Tengen, was now in the business of publishing games for various computers and consoles. But it didn’t want to be bound by Nintendo’s terms, and decided to publish unlicensed cartridges for the NES. After all, if the original Atari’s lawyers had been unable to prevent Activision from doing just the same thing for the VCS/2600, why would Nintendo’s lawyers be able to stop Atari Games?

Atari responded to engineering moves with a bolder engineering move. It reverse-engineered Nintendo’s lock-out chip, known as the “10NES,” and replaced it with its own, the “Rabbit.” The Rabbit code was entirely different from the 10NES, as far as 0s and 1s are concerned, but it was functionally similar. When a rogue Tengen cartridge was inserted into the NES, it would sing a mating song so close to what the lock expected from approved cartridges that the console would open up, and the two would play well together. The first rogue game would be “Tetris,” followed by such hits as “Super Sprint” and “Ms. Pac-Man.” On the Sega front, another third-party publisher, Accolade, started by two of the Activision founders, reverse-engineered the Genesis’ lock in 1991 for its game “Ishido” and quickly released a number of blockbusters for that platform.

Engineering responses to business disruption had been defeated by engineering means. In our never-ending dance, it was now time for lawyers to respond to reverse-engineering with legal engineering moves of their own. By legal engineering, I mean the craft of creating novel legal arguments in response to changes in an environment — in this case, technological change.

What the Nintendo and Sega lawyers noticed was that in the process of creating their own mischievous code, the one that confused the locks, Atari and Accolade had to make a temporary copy of the lock’s own original code (the 10NES and the TMSS) in order to analyze it and make an original, similarly functional code. That intermediate copying had not been authorized by either Nintendo or Sega. Atari and Accolade were therefore culpable of copyright infringement, the console manufacturers argued, making the distribution of the rogue games illegal.

The two cases, Atari Games v. Nintendo, and Sega v. Accolade, were tried in two different sets of courts for procedural reasons, but were ruled upon at the same time period and cross-referenced each other. The legal question was the same: Is intermediate copying of software code (the lock), when the sole purpose of such copying is to reverse engineer the lock and create a completely new and original code that will open the lock, illegal copyright infringement, even though the lock’s code is not at all present in the final product (the rogue key), or is this practice permissible under the fair use doctrine, since the code being temporarily copied is then discarded?

The underlying legal sub-questions were particularly complex, and both federal appeals court judges distilled their astute reasonings in clear ways, ultimately ruling that intermediate (temporary) copying of software code in the process of reverse-engineering it is generally permissible as fair use under copyright law. At the heart of their technical legal rulings was economic policy.

They focused on “the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work,” one of the Copyright Act’s fair use analysis factors, and noted that the public benefit of the copying at stake should also be factored in. In reference to the Accolade case, the judge concluded that “Accolade’s identification of the functional requirements for Genesis compatibility has led to an increase in the number of independently designed videogame programs offered for use with the Genesis console. It is precisely this growth in creative expression, based on the dissemination of other creative works and the unprotected ideas contained in those works, that the Copyright Act was intended to promote.” The judge rebuked any suggestion that Sega might suffer a loss when it came to the number of games it would itself sell (or not sell) as a result.

The Atari judge agreed: “When the nature of a work requires intermediate copying to understand the ideas and processes in a copyrighted work, that nature supports a fair use for intermediate copying,” he wrote. “Thus, reverse engineering object code to discern the unprotectable ideas in a computer program is a fair use.”

To the judge, it didn’t matter that Atari was right on principle — it had blatantly lied to get the code.

The pair of rulings had a significant impact on the industry at large, one still felt today. It would come to protect the distribution of software-based hardware emulators, such as the Connectix Virtual Game Station, which enables players to run Playstation games on their desktop computers. Perhaps even more visible as part of the retro-gaming boom of the past 30 years is the availability of a plethora of new, cheap hardware that enables nostalgic players to play the Nintendo, Atari, or Sega games of their youth without an actual NES, VCS, or Genesis, and, in many cases, without actual game cartridges either. Finally, the wide availability of new games for these old consoles developed by companies such as the new Tengen Games is enabled by the two rulings.

You might have been lured into reading this article by the promise of blood being drawn by Nintendo from Atari. But didn’t we just learn that Atari Games (Tengen) beat Nintendo in court?

No, and here’s the twist. The Atari court ruled that Atari should have been allowed to reverse-engineer the NES as a matter of principle, based on fair use. But, it continued, in this case, Atari was not allowed to invoke the fair use defense, because it came to court with dirty hands, so to speak. Atari’s lawyers’ hands were very dirty indeed. See, Atari’s engineers had actually failed to reverse engineer the 10NES. They could not figure out what that code was, so they couldn’t create a new code that would work with the console. So the lawyers took over and blatantly lied to the Copyright Office in order to obtain the copyrighted Nintendo code. That code was held at the Office under seal. In 1988, Atari’s lawyers filed an application stating that Atari was a defendant in a copyright infringement lawsuit filed by Nintendo, and needed a copy of the program to “be used only in connection with the specified litigation.” The Copyright Office obliged and provided the copy, as they are supposed to in this type of case. But the story was a lie. Nintendo was not suing Atari at the time. Atari then used Nintendo’s code to create the Rabbit code.

Upon hearing of the fraud, the judge turned to a maxim coined in British courts in 1728 and traced all the way to the Roman period of Justinian: he who comes into equity must come with clean hands. In modern language, to invoke a legal principle based on fairness, such as fair use, one must approach the bar in good faith. One who comes to court in bad faith (with “unclean hands”) will be denied a defense such as fair use.

As a result of its lawyers’ filthy hands, Atari was barred from manufacturing games for the NES. Nintendo, with its stronger legal team, subsequently “bled Atari to death,” in the words of Ed Logg, designer of Tengen’s version of “Tetris,” which was recalled by court order and is now an expensive rarity on eBay. The Tengen brand fell into disarray and was abandoned, only to be revived a year ago to do the very thing Atari had been precluded from doing because their lawyers had failed to wash their hands.

Many technology histories, including “ultimate” histories of the videogame industry that focus on “the great inventor,” are too reductive. To better understand inflection points, one must look beyond individual genius to the less sexy interplay of engineering, business, and law. Often, it’s the legal battles — and sometimes the lawyers themselves — that create significant forks in the road.

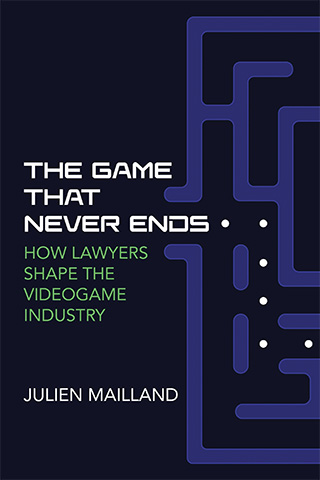

Julien Mailland is a technology industry attorney. He is also Associate Professor of Media Management, Law & Policy at the Indiana University Media School and Adjunct Associate Professor of Informatics at the Indiana University Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering. He is coauthor of “Minitel: Welcome to the Internet” and author of “The Game That Never Ends: How Lawyers Shape the Videogame Industry.” An open access edition of the book is freely available for download here.