How Greek Temples Bridged Earth and Cosmos

Places matter greatly in life. Consider the inordinate time and energy we devote to finding, acquiring, and shaping our homes — from the rooms we live in to the street, town, and region we inhabit. All of our experiences are, in fact, spatially grounded, yet we rarely think of a place as more than the backdrop to our daily activities, the setting for what we are doing: reading, walking, speaking with a friend.

For the ancient Greeks, place was anything but passive. While they developed abstract concepts of space, they saw physical space as continuous with the cosmic order — an essential unity. Buildings, especially religious ones, played a vital role in establishing and maintaining this connection between the heavens and everyday life.

Greek built environments reflected these cosmological concepts, from the domestic to the urban, the religious to the civic. The nested spheres of the cosmos, with their order and hierarchy, framed how space was understood and experienced. This idea of space as bounded and meaningful is what I refer to as Raum in my book, borrowing the German word that encompasses both “room” and “space.”

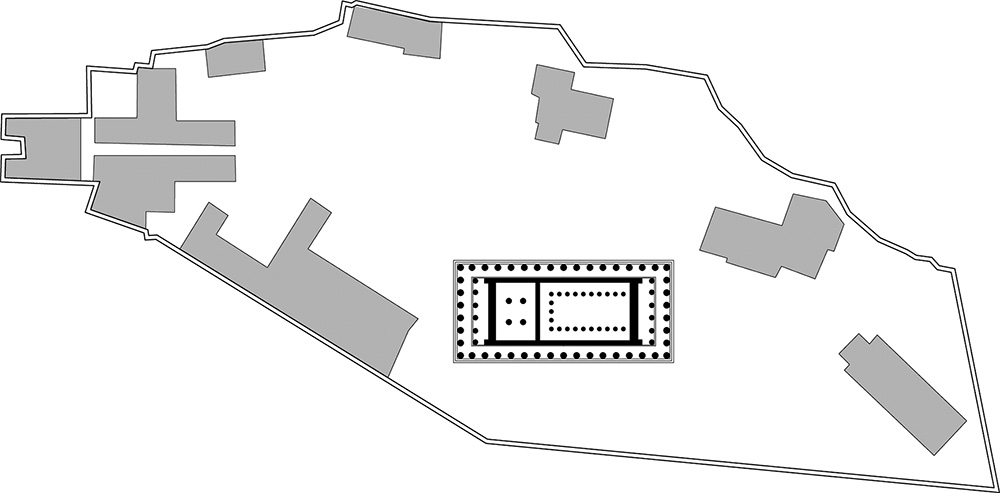

As expressions of cosmic order, Greek temples were laid out with careful attention to solar orientation and set apart from other buildings.

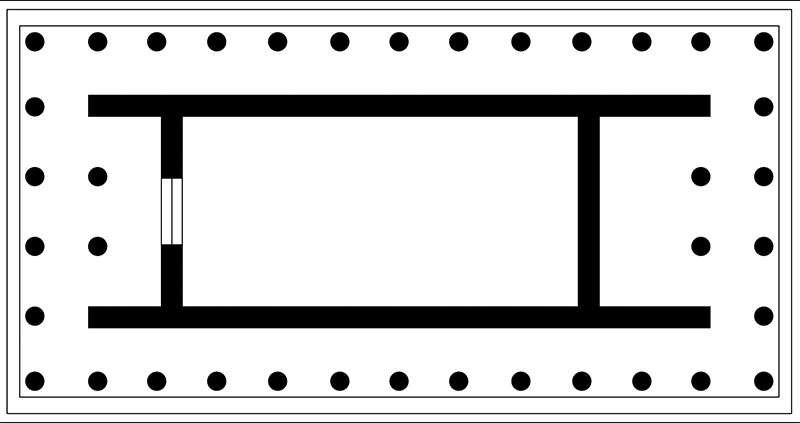

As expressions of cosmic order, Greek temples were laid out with careful attention to solar orientation and deliberately set apart from other structures. They embodied the continuity between sacred and profane realms, linking abstract cosmology to a specific location. Their highly controlled geometric proportions lent them both authority and symbolic significance. The temple’s cella (from the Latin for “small chamber”), its innermost space, was almost solidly enclosed and was considered a special kind of chamber or “clearing” (of any impurities) in which the subtle signs of the divine could be read by the specially trained priestly class.

The idea of bounded space is especially significant in distinguishing between sacred and profane realms — a symbolic contrast central to religious architecture since the earliest histories. The human act of “cutting off” one space from others lies at the root of nearly all early expressions of the sacred, from the cave to the temple. A windowless chamber arrived at through a lengthy transition from outside is not automatically sacred, but the experience of such a spatial phenomenon, removed from a continuous engagement with the senses of one’s natural surroundings, creates a new spatial feeling. A cut-off space becomes a space of potential: undefined, but extraordinary in bringing forward awareness of one’s own interior self, inverting the spatial extension of open surroundings and the attending expansiveness of sensory engagement.

The temple was a kind of cosmic spaceship, the sacred reified to the populace. Sacred space was, in effect, transferred from the heavens to the profane earth, articulated and experienced in, paradoxically, the temple’s most interior and unambiguous of spaces.

Many religions share this concept of the sacred, a temenos (τέμενος, from the Greek verb τέμνω, meaning “I cut”) — often a grove of trees, a clearing in the land, or an area within a built environment, surrounding a more sacred center space, the hieron (ἱερόν; transliterated as hierón and meaning “sacred”). The temenos in Greek temples evolved from designating sacredness by encirclement, transforming into the abstraction of a colonnaded portico (the peristasis) surrounding an interiorized cella.

A dark interior cella bears little resemblance to an outdoor space surrounded by a grove of trees. A Greek temple’s columns, some scholars argue, are a highly abstracted architectural embodiment of the sacred grove; the cella is less convincing as a reproduction of the sacred center, the hieron of “the grove,” than as something that arose from realizing that space could be artificially compressed, arranged, and made sacred — independent of the natural world.

This insight didn’t emerge overnight. It developed in the context of an architectural language of abstracted nature: of altar, plinth, podium, column, stair. Architecture could create space. The long ritualistic walk to the temenos of the sacred grove could now be spatially collapsed, telescoped inward, by creating an autonomous structure, a temple, with an interior-encapsulated space, a divine “house” for gods. Worship remained outside of temples; an empty cella remained a forbidden space, all the more mysterious through exclusion. Mystery gave the temple its significance.

The etymology of mystery is instructive: It comes from the Greek μυστήριον (mustḗrion; meaning a “mystery” or “secret” or “secret rite”) by way of the Latin mysterium; the Greek word is rooted in μύστης (mústēs, “initiated one”) and μυέω (muéō, “I initiate”), which come from μύω (múō; meaning “I shut”). Thus, it derives from the idea of shutting out, closing off, restricting entry — an example of how a spatial condition may have directly formed concepts and human understanding of the divine, preceding organized religions and their representations.

Cella access was restricted, reserved for religious rites. For privileged guests, it contained votive offerings and a cult image. It was near-purified space, stripped of all exterior phenomena, inverting the outwardness of natural space and evoking inner awareness, like an echo of one’s own thoughts or dreams.

The etymology of “mystery” is instructive: It derives from the idea of shutting out, closing off, restricting entry.

The interiority of such a space was instrumental in creating a sense of revisiting the secular world from afar. Indeed, such a space can actually feel “outside” the world or, more precisely, can make the secular world uncanny (from the interior) and estranged, as if one is momentarily occupying the gods’ own space. Paradoxically, a feeling of immensity opens in such sensory-limited situations, as if alone at sea in a tiny vessel. This all aligns so completely with general religious experience that it leaves us to speculate: Did states of wonder and religious ecstasy (from ἔκστασις; ekstasis, ultimately derived from words meaning “to stand displaced” or “outside oneself”) and the idea of cleaving the profane body from the mindful self precede or follow from the invention of the enclosed sanctuary?

Of course, many factors can instantly change such interior experiences: one’s own state of mind; the distraction of any sensory anomaly; a certain odor or acoustic condition that conjures a whole new world. To prepare the mind and body, clear distractions, and heighten awareness before entering the now-sacred space, all other liminal parts of the temple were critical to prereflective preparation: authorization (the priestly class or vetted visitors), time of day, topographic setting, podium, columns, portico, entablature, the heavy monumental door, incense, darkness, incantations.

It’s tempting to think of a Greek temple as the perfected execution of an intention, as if its designer rationally translated cosmic ideas into architecture. Yet the many distortions introduced into their geometry — the entasis (swelling) and inward tilt of columns; uneven spacing (bunching slightly toward the center of each colonnade); the curved, nonlevel temple podium (stylobate); the stretching of spacing of elements — ensured they had almost no straightforward lines or proportions. These distortions, likely introduced as optical corrections, aimed to unify the temple’s elements and adjust them for the imperfect human perceptual apparatus. Like the “distorted” glass of prescription lenses, these distortions corrected the imperfection of earthly space and place and thus allowed a glimpse of the cosmos beyond.

Christopher Bardt is a professor of architecture at the Rhode Island School of Design, where he has taught since 1988. He is a founding partner (with Kyna Leski) of 3six0 Architecture in Providence and the author of “Material and Mind” and “The Feeling of Space,” from which this article is adapted.