How Demonology Won the 2024 Election

In the days leading up to the 2024 presidential election, Donald Trump accused the Democratic Party of being “demonic,” said that former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was an “evil, sick, crazy” word-that-starts-with-a-B (“Buh-,” he teased), and openly fantasized about his enemies being shot. These statements aligned with the Trump campaign’s final messaging push about enemies within and enemies at the gates. Trump’s Madison Square Garden rally, held a week before the election, embodied this spirit; speakers called Democratic nominee Kamala Harris “the devil” and “the antichrist” and described the “whole fucking” Democratic Party as “a bunch of degenerates,” among other invectives.

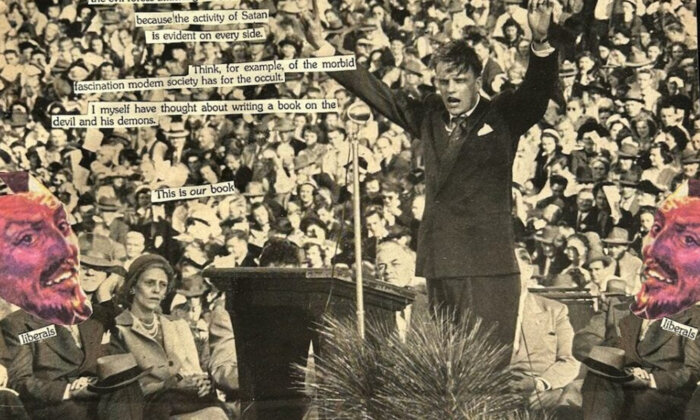

The fact that Trump won swiftly and decisively, and beyond that, gained votes across almost every demographic group despite all the vitriol and controversy that swirled in the lead-up to November 5, seems to point to a powerful and growing cult of personality. We make a very different argument in our book, “The Shadow Gospel.” Trump hasn’t built a cult of personality. Trump has inherited a cult of demonology, the origins of which extend back to the Cold War and center on a shape-shifting liberal devil mapped sometimes onto nefarious “elites,” sometimes onto economic leftism (which also rails against elites, but that’s just details), sometimes onto the institutional Democratic Party, and sometimes, simply, onto things demonologists don’t like. This is a devil that spans partisan lines and defies logical coherence.

Throughout the 2024 campaign, Trump and his surrogates, boosted by a sprawling rightwing media apparatus, seized every opportunity to highlight how the family, God, conservatives, and America were endangered by the liberal devil. All discursive roads inevitably lead back to that threat: what the liberal-leftist-elite-Democrat-Marxist them was doing to pull the country into hell, a framing that simultaneously allowed Trump to position himself as the nation’s savior.

For demonologists, the enemy is never vanquished. Once one issue or group of people is crushed, the threat will simply hop to another issue or group.

To tell this story, especially after the July 2024 near-miss attempt on Trump’s life in Butler, Pennsylvania, Trump would at times use explicitly religious symbolism and visuals. He posted one such image to X, formerly Twitter, of the Archangel Michael, a stand-in for Trump, raising a sword to slay Satan, a stand-in for Trump’s enemies. More often, Trump and his allies cast off religious rhetoric entirely to make wholly secular claims about liberals’ corrosive influence in schools, Big Tech, media, and the government. Whether forwarded by Trump or his MAGA faithful, whether outright religious or secular, these claims typically had very little to do with policy. In fact, the less specific detail or evidence the claims contained, the better, including what, exactly, made someone one of the liberal them.

As incessant as it was in its messaging about liberal/leftist evil, indeed as disciplined as it was in that messaging, the Trump campaign was not pursuing a conventional electoral strategy centered on broad public outreach. Trump stuck to MAGA-friendly audiences. He did not actively court swing voters. He simply wasn’t focused on persuading lots of different kinds of people to vote for him.

Instead, he focused on making the liberal devil bigger by attaching its threat to more people (anyone who challenged Trump) and more places on the map (anywhere that didn’t support Trump) and more ideas (anything that didn’t align with Trumpism). The center became the left. The right became the left (the “wrong” kind of right, anyway; just ask Liz Cheney). And it all needed to be vanquished. If anti-liberal demonology were a normal electoral strategy, then Trump and his deputies could put down their swords, having handily slain their devil. But for demonologists, the enemy is never vanquished. Once one issue or group of people is crushed, the threat will simply hop to another issue or group. There will always be more liberals to fight.

As scholars watching this unfold in real time, we were struck by just how old these “new” developments really were. So many of the things that were assumed to be new lows, or at least new weirdnesses, during the last few months can be traced back 10, 20, 50, 80 years, including claims that centrist politicians are Communists, the equation of diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts with the apocalypse, and endless talk about Satan among us, particularly when that talk is secular.

The collapsing of religious and secular messaging has a similarly long history. For decades, claims about threats to Christians, Christmas, or children have been filtered through cable television and other mass media. Sometimes these messages retain their religious focus; sometimes they don’t mention God at all. However sanded-down their Christian references, the messages carry all the weight and moral authority of a sermon from the pulpit or passage from the Bible. The result, which we chronicle throughout the book, isn’t just to attack “liberals,” however that term might be defined. It’s to fundamentally undermine theological Christianity and ideological conservatism. Demonology is the bipartisan enemy of anything that is grounded.

So what exactly is happening? We call the not-quite-religion on display the shadow gospel. The gospel part of the shadow gospel refers to 80 years of densely overlapping messages about a historically ungrounded, hyperbolized liberal devil.

Three frames shape the gospel’s messages. The first is outright conspiracism, which posits cadres of scheming liberals in the government or within institutions such as journalism, with granular detail given to the alleged plots and ringleaders themselves. Outright conspiratorial messages are most likely to be designated as “extreme” and tend to be most salient within far-right networks, though they also filter into mainstream conservative spaces.

The second is the anti-frame, which forwards staunch if abstract opposition to all things liberal, whether those things are described as such by self-identifying liberals or are coded as liberal by conservatives. Anti-messages are predicated on grievance, feed into narratives about beleaguered conservatives, and are a recurring focus of rightwing media.

The third is the pro-frame, which is expressed as positive support for ideals such as the family, freedom, and America. These messages are least obviously partisan and most likely to spread beyond rightwing circles.

The shadow part of the shadow gospel refers to the versions of conservatism and Christianity that have been conjured through anti-liberal messages. Just as a shadow is tethered to but cannot be equated with the solid object casting it, the shadow gospel is tethered to but cannot be equated with conservative ideology or Christian theology. What emerged in the mid-century media environment and expanded over the decades is a shadow realm of false histories and half-truths that uses the language of faith and family — and caricatures of what a liberal is — to exalt the category of “real” Americans, to hell with everyone else.

What looks like “church gospel” Evangelicalism is often just the shadow gospel in disguise.

Our analysis begins with mid-century Evangelical and rightwing activist — and later, institutional Republican — networks because that is where shadow gospel messages first emerged and thrived. Although the messages were swiftly adopted toward partisan political ends (namely, to help elect more Republicans), they were not the product of partisan politics. Their origins were, instead, strikingly nonpartisan. It is therefore unsurprising that, in the end, the messages that eventually were politicized did not stay confined to the political right; and neither did their implications. Shadow gospel messages have also circulated widely within the political left — at least, what gets called “the left.”

The relationship between left and right is central to the story we’re telling. But the polarization frame, which posits a basic coherence and enduring essence to “left” and “right,” misses something important when it attributes the chaos of the U.S. political landscape to intensifying clashes between leftwing liberals and rightwing conservatives. People are obviously clashing, and intensely. Our claim is that the left/right polarization framework does not fully explain why.

The shadow gospel helps tell a clearer story about that clash. It begins with (but ultimately deviates from) the conventional account of Evangelical influence. That account goes like this. In the 1970s, very conservative Republican and Evangelical leaders came together to push the Republican Party platform toward more conservative positions on issues like abortion and same sex marriage. This was an advantageous arrangement for both groups; Republicans benefited because Evangelicals were an untapped but increasingly powerful voting bloc that would give the Party an electoral advantage, and Evangelicals benefited because it put them and their interpretation of biblical teachings in the driver’s seat of policy-making. The synergy between Evangelicals and Republicans is what allowed Evangelicalism’s “Three Bs” of belonging, belief, and behavior to remake U.S. politics.

The unquestionable influence of Evangelicalism is, quite literally, where the book project started on January 6, 2021. Like many people in the United States and around the world, we were both trying to make sense of the violence and chaos at the U.S. Capitol as it unfolded. But the more we talked about the role of religion, or at least the role of Christian symbology, within rightwing political networks, the more we realized that there was something strange about the relationship between religious and secular media, and something even stranger about the relationship between religious and secular belief.

The conversations that followed uncovered another oddity: the anomalies generated by the conventional account of Evangelical influence. Most conspicuous is the fact that since the early 1980s — the time of Evangelical Christianity’s supposed rise in cultural influence — Evangelicalism has remained stagnant in terms of the number of believers. Measured as a percentage of the population, there are no more Evangelicals today than there were in the 1980s; Evangelicals now, as then, make up about a quarter of the population. Evangelicals have not even grown as a percentage of the Republican Party since the Reagan era. What has changed is the secular population, which has risen sharply since the 1980s.

The numbers suggest that the last 40 years have been a conversion and outreach failure for Evangelicals, rather than a period of increasing influence and power. Indeed, the only significant rise in Evangelical identification during the last four decades came under the Trump presidency, but, critically, that was not accompanied by a similar rise in church attendance.

Further, while activists might have been able to link Republican Party machinery with Evangelical leadership during the 1970s, the full fusing of Republican and Evangelical identity within the churchgoing public didn’t happen until the 1990s. This is to say nothing of how improbable the forging of Republicanism with Evangelicalism was in the 1970s; it might seem like a natural fit from our contemporary perspective, but pre-Reagan Republicans and Evangelicals were far from monolithic.

Something besides Evangelical believers, churches, and theological tenets themselves had powered Evangelical influence within the Republican Party and U.S. culture.

The idea that a few rightwing activists single-handedly changed the course of U.S. politics in the 1970s is compelling, but is complicated by the fact that these same activists were unable to make overwhelming electoral headway for another 20 years. Social science research conducted by Clyde Wilcox in the 1980s adds to this complication. In his study of the Religious Right, Wilcox identified significant demographic and attitudinal similarities between Christian rightwingers of the 1950s and the Religious Right of 1980s that couldn’t have been engendered by Republican organizing because it predated that organizing by decades. Wilcox’s work suggests that the Republican Party inherited a powerful (if ideologically slippery) coalition, but can’t be credited with building it.

What became clear to us was that the existing stories — about Evangelicalism and about rightwing activism — were incomplete. Something besides Evangelical believers, churches, and theological tenets themselves had powered Evangelical influence within the Republican Party and U.S. culture. The argument we developed over the subsequent two years was that a gospel had fueled the relationship between the religious and the secular; a gospel had fundamentally shaped, and was continuing to shape, the American landscape. But it wasn’t the church gospel. What looks like “church gospel” Evangelicalism is often just the shadow gospel in disguise.

The prognosis our book offers isn’t a good one. What it provides, we hope, is a way to make sense of what just happened, starting with the insight that Trump’s victory wasn’t actually a victory for Trump. It was a victory for demonology. As a mode of thinking and political ethos, demonology can be resisted. But it has to be identified as a possessing spirit first.

Whitney Phillips is Assistant Professor of Digital Platforms and Media Ethics in the School of Journalism and Communication at the University of Oregon. She is the author of “You Are Here,” among other books.

Mark Brockway is Assistant Teaching Professor in Political Science at Syracuse University. His research centers on religious and political identity and activism as expressed through party politics, in the electorate, and in governmental institutions.

Phillips and Brockway are co-authors of “The Shadow Gospel,” from which this article is adapted.