Hervé Guibert: 'A Man’s Secrets'

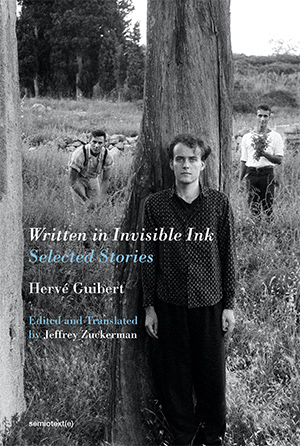

Hervé Guibert published 25 books before dying of AIDS in 1991 at age 36. An originator of French “autofiction” of the 1990s, Guibert wrote with aggressive candor, detachment, and passion, mixing diary writing, memoir, and fiction. In his short story “A Man’s Secrets,” written quickly and out of intense grief the day after his friend and mentor Michel Foucault’s death, Guibert recounts three of Foucault’s deeply buried childhood memories, released by the hand of a surgeon. “It took me two or three years before publishing it, before even having it read,” Guibert said in an interview published in 1992 after his death. “Then I disguised this character, my thoughts of him were of absence, of lack. Were unbearable. His very image became wholly evanescent. I so needed this friendship to live that, when he was dead, I had to forget it.” The story is excerpted from “Written in Invisible Ink: Selected Stories,” published by Semiotexte(e) in 2020.

When it came to trepanning, the specialist said: I could never touch this brain, it would be a crime, I would feel like I was attacking a work of art, or hacking at perfection, or burning a masterpiece, or flooding a landscape that needed to stay dry, or throwing a grenade into an exquisitely structured termite mound, scratching a polished diamond, ruining beauty, sterilizing fertility, tying off the canals of all creation, every cut of the blade would be an assault upon intelligence, thrusting iron into this divine mass would be an auto-da-fé for this genius; only a barbarian, an illiterate, an enemy would commit such a crime! The enemy existed. Sarcastically, examining the three lesions spreading across the scanner’s images, he says: how could such brilliance be left to rot? We have to open this. This intelligence had pierced him, personally, not by name, but by condemning all the deceit in his system, in several books. The man of the mind had castigated the man of law: the doctor, the judge; the philosopher had ultimately accused his ancient predecessors of abuse of thoughts; in their texts, he tried to find the exact moment when the thread was lost, imperceptibly but insidiously, when the right words, drawn from the right thoughts, slipped ever so slightly, were recovered maladroitly, and turned into wrong words, oppressive words. The surgeon took pride in assailing such a fortress, especially considering how he called his prestige groundless; a man’s head, he said to his assistants, is nothing more than a bit of flab, of cured meat. But when the orb was opened, he was astonished by the powerful beauty that matter exuded; his disdain was as mute as his tongue, and his stylet fell from his hands; all he could do, now that he had been converted, was contemplate. The brain was no longer a simple, tender walnut with manifold, indecipherable convolutions, but a luminescent, teeming terrain as yet uncongealed by anesthesia, and every fiefdom was busy working, gathering, connecting, charting, drifting, damming, rerouting, refining; three strongholds had collapsed, that was easy to see, but all around the moat kept golden thoughts and laughter flowing. The most noticeable veins carried along all sorts of nasty old ruined things, prison turrets, torture vises; but the whips seemed to gleam royally like scepters, and the gags were woven like finery. Exposed discourses glittered on the surface, opened up to derision; their reek of arrogance was absolved by their aroma. Digging just a little revealed corridors full of savings, reserves, secrets, childhood memories, and unpublished theories. The childhood memories were buried deepest of all, in order not to clash against idiotic interpretations or poorly woven veils that were meant to be enlightening but which instead shrouded the work. Two or three images were buried in his vessels’ depths like vile dioramas. The first one showed the young philosopher led by his father, himself a surgeon, through a Poitiers hospital room where a man’s leg had been amputated, that’s how the boy’s manliness gets shaped. The second revealed a typical backyard the little philosopher was walking past, which was aquiver with the recent news: right there, on a straw mattress, in this sort of garage, was where the woman all the papers were calling the Poitiers Prisoner had lived for dozens of years. The third retold the beginning of a story, wax figures coming to life through the machinery hidden beneath their clothes: in high school, the little philosopher, who had been the top of his class, was threatened by the sudden and seemingly inexplicable invasion of an arrogant band of little Parisians who were sure to be more talented than the rest. The ousted philosopher-child came to hate them, insult them, hurl all sorts of curses upon them: the refugee Jewish children in the area did disappear by being deported to the camps. These secrets would have sunk in the Atlantis ever so slowly, ever so sumptuously chiseled, suddenly shattered by lighting, had a vow of friendship not raised the vague and uncertain possibility of their being passed on . . .

Each of these strongholds were threatened, one by one: the cache of proper names emptied. Then it was personal memories that were very nearly ruined: he fought to keep the scourge from winning out. Even the existence of his books vanished: what had he written? had he even written? Sometimes he wasn’t sure at all. The books there, in his hands, could have borne witness. But the books weren’t himself, he had once written that and he remembered it still: that the book wasn’t the man, that between the book and the man was the labor that had dissociated the two, and sometimes drove them apart like two enemies. But was that actually what he had written? He hesitated to return to the text itself, he was afraid to find himself locked out as an idiot. So he wrote and rewrote his name on a piece of paper, and underneath he drew rows of squares, circles, and triangles, a ritual he had taught himself to verify his mental integrity. When people came into his room, he hid the paper.

He had to finish his books, this book he had written and rewritten, destroyed, renounced, destroyed once more, imagined once more, created once more, shortened and stretched out for ten years, this infinite book, of doubt, rebirth, modest grandiosity. He was inclined to destroy it forever, to offer his enemies their stupid victory, so they could go around clamoring that he was no longer able to write a book, that his mind had been dead for ages, that his silence was just proof of his failure. He burned or destroyed all the drafts, all the evidence of his work, all he left on his table were two manuscripts, side by side, he instructed a friend that this abolition was to continue. He had three abscesses in his brain but he went to the library every day to check his notes.

His death was stolen from he who wished to be master of his own death, and even the truth of his death was stolen from he who wished to be master of the truth. Above all the name of the plague was not to be spoken, it was to be disguised in the death records, false reports were given to the media. Although he wasn’t dead yet, the family he had always been ostracized from took in his body. The doctors spoke abjectly of blood relatives. His friends could no longer see him, unless they broke and entered: he saw a few of them, unrecognizable behind their plastic-bag-covered hair, masked faces, swaddled feet, torsos covered in jackets, gloved hands reeking of alcohol he had been forbidden to drink himself.

All the strongholds had collapsed, except for the one protecting love: it left an unchangeable smile on his lips when exhaustion closed his eyes. If he only kept a single image, it would be the one of their last walk in the Alhambra gardens, or just his face. Love kept on thrusting its tongue in his mouth despite the plague. And as for his death it was he who negotiated with his family: he exchanged his name on the death announcement for being able to choose his death shroud. For his carcass he chose a cloth in which they had made love, which came from his mother’s trousseau. The intertwined initials in the embroidery could bear other messages.

As the body was collected in the morgue’s rear courtyard, masses of flowers lay all around the coffin: in wreaths, in rows, from editors, from the institute where he had taught, from foreign universities. On the coffin itself stood a small pyramid of roses among which a band of mauve taffeta revealed and concealed the letters of three names. The bier traveled the whole day, from the capital to the rural village, from the hospital to the church and from the church to the cemetery, it passed from hand to hand, but the pyramid of roses, which the florist had not stapled or taped to the wood, was never knocked off the structure. Several hands tried to move it. Either those hands were immediately caught in a moment’s hesitation after which they reconsidered, or other hands reached out to stop them. An occult, imperious order bound the pyramid of roses with its three names to the coffin. When the coffin was gently set in the pit, the mother was asked what should be done with this spray of flowers, and she gestured, she who was not crying, to leave them on the coffin. Nobody got rid of the letter that someone had left when the body was collected, or worried about whether it contained love or hurt, the cut flowers buried it. A tall young man with bare shoulders, in a leather jacket, sunglasses, stood in the distance, accompanied by an old crooked man who seemed to be his father, or servant, or driver; from the capital to the village, from the morgue to the church, from the church to the cemetery they had traveled in an elegant sports car. I had never seen this young man and when he threw flowers into the ditch after me with his sunglasses still on, I suddenly recognized him and I went up to him, I said: are you Martin?, he said: hello, Hervé. I said: he always wanted us to meet, and now we have. We kissed each other’s cheeks and perhaps we kissed his at the same time over the grave.

Hervé Guibert (1955–1991) was a writer, a photography critic for Le Monde, a photographer, and a filmmaker. In 1984 he and Patrice Chereau were awarded a César for best screenplay for “L’Homme Blessé.” Shortly before his death from AIDS, he completed “La Pudeur ou L’impudeur,” a video work that chronicles the last days of his life.