Cecilia Pavón: The Flawed Concept of Coupledom

Poet, writer, and translator Cecilia Pavón emerged in the late 1990s as one of the most prolific and central figures of the young Argentine literary scene. A cofounder of Buenos Aires’s independent art space and publishing press Belleza y Felicidad, Pavón pioneered the use of “unpoetic” and intimate content — her verses often lifted from text messages or chat rooms, her tone often impish, yet brutally sincere. Pavón’s stories, the writer César Aira has said, are “high-precision lenses for seeing the daily utopias of reality.”

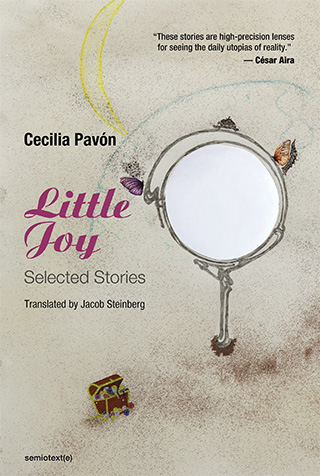

The story that follows, “The Flawed Concept of Coupledom,” is not actually about coupledom but something deeper and more interesting. It begins with a fleeting thought, an idea for a title, one of so many “luxurious titles rich with meaning that will never serve any purpose, because the text that should follow them never gets written.” This “small idea” then branches off and takes us somewhere beautiful and unexpected. “The Flawed Concept of Coupledom,” translated by Jacob Steinberg, is excerpted from “Little Joy” (Semiotext(e)), a collection of Pavón’s finest short stories written between 1999 and 2020.

From one moment to the next, my ideas changed completely. I can’t remember exactly how it happened, but I do vaguely remember that less than thirty minutes ago, I was trying to come up with a title and concept for a story that sounded brilliant. But now I can’t remember its exact formulation. I know it was some expression about couples. Now I’m calling it “The Flawed Concept of Coupledom,” but those weren’t the exact words. It was something far more interesting, synthetic, and deeper than this title. And while I know how the phrase felt, I can’t remember what “aesthetic” sensation it produced.

It can be quite frustrating.

Be as it may, what surprises me isn’t that I forgot the expression. I’ve already accepted that forgetfulness is a key part of writing, of literature. For me, what I publish and sell (which, as an aside, I do very little of) aren’t books but rather all my small ideas — whether brilliant or moronic, but either way, surprising and liberating (at the time)…or libertarian — I have throughout the day that don’t make it to the page. Generally, these ideas turn into titles. And what beautiful titles they are! (Which isn’t to say they are slogans.) Luxurious titles rich with meaning that will never serve any purpose, because the text that should follow them never gets written. I’d love to do a gallery exhibit of titles. I envision walking into a large gallery illuminated by a bright blue light, and there, my titles are all on display. Not on the walls, because they wouldn’t exactly be paintings. What I’m picturing is a mental gallery whose address and coordinates I, and only I, have. To get to my showing of titles, I need only lie down in my bed with turquoise sheets and close my eyes… Each title leads to another — sometimes related, sometimes not — like a necklace of fake beads made by someone crazed. Although the way I dream them, they’re one great whole. Suddenly, the blue gallery becomes ectoplasm, and the titles and my arteries are one and the same, a single unit. After “The Flawed Concept of Coupledom” comes another title: “The Creator and the Fires of Artifice.” Each title gives way to a special moment in my life where my mind tries to understand everything it sees or experiences. And then there is a great stretch of white walls, because aphasia is also a part of this gallery. That space where poetry ends and life is but a golden corner.

I don’t know why I thought that the concept of coupledom was bad. Unfortunately, I can’t remember all the feelings and sensations that brought me to think so anymore. Because now I’m happy and feel blessed since you gave me a blue, British hat while walking along Paseo Ahumada, and it was a lucky day. That’s the next title I’ll add: “A Lucky Day.” Something like that to try and trap the luck before it fades away. I think the title about the flawed concept of coupledom is from November, and things have changed since then. Now it’s January, and coupledom is perfect. I want it on the record here. Each night, we watch a movie on Netflix. And each morning, we have coffee at Harvard, a café-bar at the corner of Alberti and Hipólito Irigoyen Street. Life is simple, and titles don’t come to me like they did before. Suddenly, I realize that the day has gone by, and I haven’t thought of a single one. My mind’s gallery begins to clear out, and reality bursts in like an onslaught of occurrences that need not be named. Could this be happiness? And if so, is happiness the opposite of writing? I move forward on the blank page, and a minor angst settles on my shoulders. It’s like an assault. As if some strange animal had entered my room, an animal I’ve never seen before. Why can’t writing and happiness be simultaneous? The animal says I must light a cigarette and write a new title: “Ballad of a Woman Who Smokes.” It commands me to go buy three looseys from the corner store across the street. The animal, which could be an alien visiting from another universe to infect me, reminds me that I used to write to earn luck, and now that I’ve got it, it doesn’t make sense to keep stockpiling phrases on paper.

But in the afternoon, I get dressed to go to work. I teach for a living, and I have to run a workshop for kids at the Modern Art Museum of Buenos Aires. I wear a t-shirt with a print of bold colors — a burst of vibrancy. I feel like it’s a good way to keep the participants’ attention. I was mulling over and preparing the workshop for two months with a girl from the museum. The kids will work in the gallery, writing anything they want on a wooden board. I’ll tell them they must ask the paintings questions and then answer them, as if they themselves were the works and could talk. In the middle of the gallery, there is a polished metal sculpture. Maybe it’s steel. It’s a mass with irregular edges. It could be a piece of scrap metal from a spaceship or a crumbled piece of paper. A 12-year-old boy asks, “In the world you come from, how big are you and what are you? Are you a small part of something much bigger or are you something huge in a world of tiny, negligible things?”

The other participants and I stare at him entranced. We all think it’s a brilliant question. And what’s more, we love his use of the word “negligible.” If everything in the world can be a part of something else we don’t know, then it’s likely that my mental gallery of titles — an idea that gives me comfort and anxiety at the same time — has another meaning aside from the one I’ve given it. If things are like that, as Nehuel says, then certainly everything I write and everything that comes to me has nothing to do with me or my life story or happiness or coupledom or the blue hat or luck… They must be mere fragments of something much bigger or smaller that exists in another dimension.

Cecilia Pavón is an Argentinian poet and writer. This story is excerpted from “Little Joy,” a collection of her stories written between 1999 and 2020.