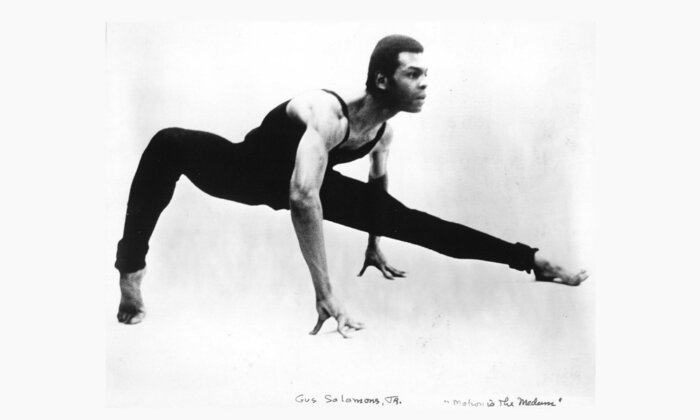

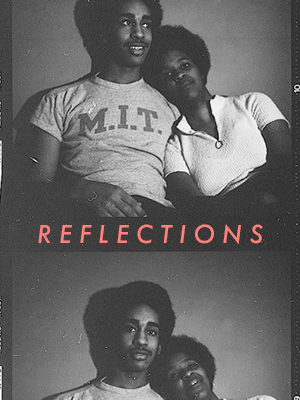

Gustave M. Solomons, Jr.: Reflections on the Black Experience at MIT

Edited and excerpted from an oral history interview conducted by Clarence G. Williams with Gustave M. (Gus) Solomons, Jr., in New York City, 20 March 1996. This interview first appeared in the book “Technology and the Dream,” which is now freely available for download. Several interviews from the book have been made available on the MIT Press Reader as part of our Reflections series.

I grew up in Cambridge, halfway between Harvard and MIT, on Inman Street. I loved school. Kindergarten year I had tonsillitis. I was out of school a lot with sore throats, so I had my tonsils taken out. After that, from the first grade through the twelfth grade, I was absent only one day. I was very proud of that. There was nothing I liked better than going to school. I was smart because I didn’t know that I wasn’t supposed to be. Actually, I was the salutatorian in high school. I was first in the college course, but a girl in the commercial course—the secretarial course—had a higher average. So I was salutatorian.

But anyway, that all changed when I got to MIT. I had never gotten less than a ninety on a quiz in high school.Well, at MIT, I never got above a sixty. I would get, say, twenty-three on a physics quiz and think,“Oh my God, I’ll have to go to BU and study music education.” I was sure that I would not make it through my first year at MIT. But at MIT they graded on a curve.

That was a tough year?

“Oh! Physics?” I knew e=mc2, but it was high school physics. I didn’t know how to think, I didn’t know how to really solve problems. I knew how to memorize. I had a photographic memory. I could memorize a script the first time I’d read it. That’s how I got through high school, I just memorized everything. I still know all my lists of prepositions and helping verbs and all that stuff.

Well, at MIT you had to think, you had to know how to solve problems. That was a big revelation and I never really learned how to do that, I have to admit. I still memorized the formulas. There was a wonderful guy who had been an MIT professor and who had gotten fired for some kind of ethical slip-up, so he had set up a little store front across the street from East Campus where he would tutor. This man was a brilliant teacher. He made his living by charging five dollars to the students to get boned up on the quizzes that were coming up—physics, chemistry, and math. I was there every week, and he would give us the formulas that we needed. I would memorize them and do the quizzes. I would still get a twenty-three, but at least I was higher than enough others that I didn’t flunk out.

Physics got interesting fourth semester. I enjoyed mechanics because I liked to put things together and build stuff, so that was fun. And nuclear physics, the fourth semester, was exciting because we had graduate assistants who would teach us what they were discovering in the laboratory that morning. This was nuclear physics! I had no idea what they were saying. I don’t think some of them really did, either. A lot of them, of course, were foreign students who didn’t have a real good grip on the English language, so we couldn’t understand what they were saying anyway. But then we would go across the street at East Campus and learn the formulas we needed.

Ever since I was a little kid, I liked performing. I did that as a major hobby, but my father — you know, MIT man, electrical engineer — “What are you going to do for a real job?”

But my upbringing before college was normal—grade school, high school, college preparatory—and I was interested in theatrics. I did a lot of children’s theater. In high school I was in the drama club. Ever since I was a little kid, I liked performing. I did that as a major hobby, but my father—you know, MIT man, electrical engineer—“What are you going to do for a real job?” It was assumed that I would go to college, so I applied to Harvard and MIT and maybe Yale, Princeton, and Carnegie Tech. But there wasn’t a question I would get into anywhere I applied in those days. Then, MIT had five full-tuition scholarships for Cambridge residents. Harvard didn’t have anything like that. They gave me a scholarship, but MIT’s was full tuition.

So I said, “Okay, I’ll go to MIT.” The way I selected my course was—and this is embarrassing, so maybe I shouldn’t tell you—that I didn’t like to read. I looked through the catalogues when it came time to choose a college to see what courses probably involved the least reading. And I thought, “Well, architecture—that looks a little artistic, that might be kind of fun, making models and drawing things. I guess I’ll be an architect.”

That’s how you decided?

That’s how I decided. I was not a mature sixteen-year-old. Actually, I was kind of young because I had gotten into school early. When I graduated high school, I was just barely sixteen. So I went into MIT early.

Before you go on to MIT, could you talk a little bit about your father and mother and family?

They were great people whom I didn’t get along with all the time as I was growing up, because I was spoiled and willful. My mother, I think, secretly enjoyed the fact that I performed. She really supported my little recitals and plays. She had done some theatrics at church. She liked to sing and she was in plays. My father was, in a way, the prototypical MIT product of his day. He was very involved in what he did, his electrical engineering, and he was smart as a whip.

He came to MIT when?

He graduated in ’28.

He graduated in 1928, and didn’t he do some things that are on the record now?

After school? Sure. He worked at Bethlehem Shipyard for his whole career. He had one job. Then they sold out to General Dynamics and he retired. During World War II, he was doing defense work, building ships. When he retired, he ran for school committee because he was active in the community.

My parents were of a generation that was aspiring to assimilate, and that was the ethic with which I grew up.

We lived in an Irish Catholic neighborhood. There were one or two black families, but it was mostly Irish and Greek and Italian and Portuguese. Those were my friends growing up—no black community at all. My parents were of a generation that was aspiring to assimilate, and that was the ethic with which I grew up. We were solidly middle class. There was enough money and everything. I had whatever I wanted and more than I deserved. I got all the toys I wanted. I wanted a chemistry set, I wanted a magic set, I wanted a bicycle, I wanted a skateboard and skis. I got them all.

Where were your parents from?

My mother was born five blocks from Inman Street on Union Street. She lived in three houses her whole life. One was on Union Street where she was born. She moved into Inman Street next door to my father’s house. She got married and moved next door. About my father’s family, my younger brother knows all this stuff because he asked. I never sat down and said, “Okay, tell me the story.” My father’s family is from the Dutch West Indies, from Aruba. I don’t know how my paternal grandmother and grandfather got together, but at some point they lived on a farm in Brooklyn. My father was brought up on a farm in Brooklyn and at some point moved to Cambridge.

You mentioned your brother. What was his name?

Noel. He’s six years younger than I am.

Now, is he the one who was a professor in nutrition here at MIT?

That’s him. That’s my brother.

I knew I knew that last name.

My father went to MIT and I went to MIT. They wanted my brother to go, but he went to Harvard to be a doctor. Actually, he went to Harvard to be a biochemist. Then he came home one day and said, “Somebody just discovered what I was going to devote my life to,” and he switched to pre-med and became a doctor. Then MIT got him finally after he graduated.

Where is he now?

He’s in Guatemala. He’s a genius down there.

Is that where he always would go each summer?

No. He went to Peru and to Colombia—Cali— and to Nicaragua, I think. When he started getting into his nutritional research, he was doing it down there. He was getting in touch with Latin America. I think it was around the time of the earthquake in Guatemala that he went. He was there cleaning up after the earthquake and he started a clinic. I don’t get all this history straight, but now he is the head of the clinic that is run under the auspices of the Hospital for Eyes and Ears. It’s called CESSIAM—The Center for Sensory Impairment and Aging and Metabolism.

He really loved going and doing that kind of research. I think everybody at the Institute knew he was outstanding, but he didn’t want to play the politics involved.

Right. He got out of this country because he hates everything about the way this country treats black people. I saw him. I went to Guatemala on the Tour from Hell in June 1995. The reason I went was—I was a little suspicious about the whole arrangement—that it was a chance to see Noel. That was really terrific. He has an adopted Guatemalan boy who was the son of one of his assistants at the lab, and this woman and her husband were shot by the guerrillas. He adopted their son. It turns out her sister is his housekeeper, so he and she and his adopted son and her daughter all share a house.

So all three of you, in one way or another, have been associated with MIT in very unusual ways.

Yes. Well, my father’s way was the most usual, I guess, because he belonged there. He was smart enough to be there. I guess it was unusual then because he was so rare, being a black person. I was there by accident. I really wanted to be in show business, and that’s what I did most of the time I was there. I did Tech shows forever. I got an award for doing Tech shows.

So this was when you were an undergrad?

Yes, I was moonlighting. I would study dance at night after my first year. I was in the Tech show the first year, and then I decided I wanted to go and study modern dance. So I went at nights and studied modern dance.

And you went to one of the best in the area. When you think about MIT, your undergraduate program, what are the highlights for you, whether they were ups or downs?

The highlights? Academically, design was great. I enjoyed the creating and the way it was taught. I had no idea what to expect. I thought we would learn about the orders of Greek columns. The second year, after that awful first year when we all had to do physics and math, we got into the studio. There were drafting tables and they brought us in a piece of paper with a problem on it. They said, “Solve this problem, build this thing.” That’s how we learned how to do it. That part was great and the people, my classmates, were also wonderful. Some of them I’m still in contact with. They were good.

I spent an awful lot of my time across the street at Kresge, of course, doing drama shop and Tech shows. I guess the drafting room and Kresge were the best things about MIT for me.

There was also something about that wonderful old building that I liked a lot. I have dreams still about the octopus, Building 7 and all the way down to Building 10—that endless, endless, endless corridor. God, what a piece of planning that was! And the ironic part about the drafting rooms is that the architects are behind this monumental stone façade, so they have no windows. I spent an awful lot of my time across the street at Kresge, of course, doing drama shop and Tech shows. I guess the drafting room and Kresge were the best things about MIT for me.

Did you have any role models or mentors that stand out in your mind during that time? Any faculty?

No, I had kind of crushes on various teachers. I remember Marvin Goody was our second-year architecture teacher. He was six-feet-six. I was six-foot-three in those days, now I’m six-one-and-a-half. He was very tall. And there was Bill Bagnall, who wore hand-knitted socks and Marimekko ties and had one of those bony, gaunt faces, but was extremely sexy. Women couldn’t stay away from him—men either. I don’t think he cared, but in 1958 you didn’t talk about it. He had a little round domestic wife and a lot of girlfriends. But I didn’t really identify with any of my teachers. Certainly there weren’t any black people at MIT.

Do you recall how many blacks were in your class?

In my architecture class, there was me. In my whole class, my entering class, I can’t remember. There may have been a half dozen, but I don’t think so. I think there were a half dozen women. I don’t remember. Maybe there were one or two other blacks, but I think they were from Africa— foreign students. I was not aware of race in those days. I identified with everybody that was around me.

You say you weren’t aware—do you have any sense about when you did become aware?

Yes. When I came to New York I had to learn how to be “colored” because I was in a show. At the first rehearsal, they gave us a step. It went duh-duh-duh, Free Twist! And I said, “What? Free twist?” I knew Chubby Checker’s twist, but they started and I looked around amazed and said, “Whoa! What is that?” I had some trouble “getting down.”

Actually, I have a good friend now who was in Tech shows with me then who recently said, “You know, Gus, there was a lot of discrimination around you that you didn’t see.” I was completely oblivious to it. She recalls an incident in a restaurant, Ken’s at Copley. We went in to eat something and this waitress was evidently very rude to me. I was simply unaware of it. My friend said that, as we were going out, she went and read the riot act to that waitress. But I was just oblivious. I was happy and I was having a good time. I saw my goal, whatever it was, and I went for it. I was really oblivious to any kind of discrimination or racial hatred.

At home we didn’t deal with emotion. My mother was always happy and my father was always neutral. I didn’t have any real emotional interaction with them. I used to get mad, but it wasn’t real anger. I mean, we didn’t deal with anger. It was just a tantrum and then it was over. So I never learned how to deal with emotion or how to perceive it in other people. I also never learned how to be who I was. Part of that had to do with striving. My self-worth came from the approval of other people, and I really knew how to get that approval. I was always special because I was the only black in whatever situation I was in, so I was not a threat to them. I was treated specially, I guess, because I was different, and I just thought I was being treated specially because I was terrific!

Finding out about being black happened when I came to New York and had to get an apartment. We went through the regular routine of reading the Village Voice, and going to the apartment or calling up and saying, “Is the apartment available? I’ll be there in twenty minutes,” and arriving and having the landlord say, “Oh, we just rented that one.” I would think, “I told you I was coming. What happened?” After a while, some of my friends from the show began to point out, “Gus, get a clue.”

We went through the regular routine of reading the Village Voice, and going to the apartment or calling up and saying, “Is the apartment available? I’ll be there in twenty minutes,” and arriving and having the landlord say, “Oh, we just rented that one.” I would think, “I told you I was coming. What happened?” After a while, some of my friends from the show began to point out, “Gus, get a clue.”

So I started to get a clue. That was 1961. Then came Kennedy and the Civil Rights Act, so things got better. I didn’t realize they had been worse, but they got better. For me they were good, and everybody started getting along. Then the shit hit the fan when Nixon got into office, and then Reagan tacitly made it all right to hate again. Since then it has gotten worse and worse and worse.

You do think things have gotten worse?

I ride a bike, and it doesn’t matter what I’m wearing, if I have my helmet and walk into a building on 57th Street to a dinner party as a guest, it’s assumed that I’m the delivery boy. I don’t even get angry anymore. Just the fact of being a black man anymore is an automatic threat to certain people.

I enjoy what happens when I’m thrown into a situation with a bigoted stranger and they have to talk to me. As soon as I speak, they realize that I’m not a criminal or whatever they thought. And a kind of exhale happens, “Oh! A real person!”

The other day, I was going to my chiropractor. A woman and I were waiting for the elevator. The elevator came. I got in and she hesitated. Another man, a white man, walked into the elevator and then she got in. I know if he hadn’t shown up, she would have waited for the next one. By now I’m sometimes bemused and sometimes frustrated by it, but I’m never really angry because I don’t want to deal with anger. I enjoy what happens when I’m thrown into a situation with a bigoted stranger and they have to talk to me. As soon as I speak, they realize that I’m not a criminal or whatever they thought. And a kind of exhale happens, “Oh! A real person!”

I know you did something significant in terms of architecture at MIT not too long ago. You did some work in one of the lobbies. Could you talk a little bit about that?

You mean dance work? I danced in the lobby in ’73. We did a couple of lobby installation pieces in ’73. I guess I was an “illustrious alum” at that point. I said,“I’d like to do some dancing for you,” and they said fine. I don’t even remember the mechanics of it, but it was easy. Then we went back and did it again.

I’m just writing an essay. I had to look it up because both things happened in the same year, ’73. I had done some stuff in Boston at WGBH as well. I did a big video piece. I was still well known in Boston.

Now, have they offered you to come back to, say, be a visiting lecturer or something like that?

No. And MIT just eliminated their dance program. That particular program, I think, was the wrong program for MIT. But if that’s an open option, now is the time. The media center has all this potential for doing wonderful things with dance, and I don’t mean having classes for recreation and fitness. I was on the president’s visiting committee for the arts and humanities for several years. Unfortunately, I almost could never make the meetings because of my schedule. But the one visit I did make was discouraging because at MIT still, even though the community is now much more in evidence than it was, the arts are still kind of bastard step-children, except maybe music. But it’s chamber music. Come on! Bright scientists who can play violins? That’s not what music should be doing at MIT, you know? Geez! And dance, the same. I think the visual arts probably are using the technology more effectively. I’d like to work with the media center on exploring the interface between human motion and technology.

As a matter of fact, Sandy—who was the head of architecture, Stanford Anderson, is that right?— was in contact with me about something totally else, a team architectural project that we did when I was an undergrad that he wanted to get some information about. He didn’t even know I was an alum or a dancer. Something may happen there, but I would like to do something at MIT.

I know we have a person who is an associate provost for the arts now. The woman who first came there four years ago to hold that position is Ellen Harris. She came from the University of Chicago. She has done a wonderful job. She has developed this resident artist program.

When you think back on your career so far, where did you get all this creativity? I’m trying to find out where you got these ideas.

I just didn’t think I couldn’t. Nobody said you can’t be whatever you want to be. I’m starting to feel that now. I am going through mid-life crisis and all that stuff. I look at the dancers coming up. My dancers, those guys, what they can do technically is just so far beyond what was even possible when I was coming up. The performing opportunities that are available for me now are fewer than they were, than they used to be, partly because I’m older.

I’m supposed to be “established,” which means that I should have now a superstructure. I should have an executive director, a board of directors, a this and a that. But if I had done that, I would now simply be out of business. I would be broke. I consciously kept my work on a small scale so that I could have the freedom to experiment, to do a piece with radios, say, in a museum instead of a piece that could be presented in a conventional theater. I’ve been fortunate in that a lot of people know me in the field and I have students now who are hiring me for residencies and commissions.

I consciously kept my work on a small scale so that I could have the freedom to experiment, to do a piece with radios, say, in a museum instead of a piece that could be presented in a conventional theater.

I got this job full-time at NYU in ’94, and that’s a mixed blessing. It’s full-time, it has benefits, it has a health plan—I’ve got to think about that—but it won’t let me have my time. I mean, I’m in trouble for taking two weeks off now to go to VCU, Virginia Commonwealth University, because there are things that I have to be doing here. There are times like this, winter break, when I can arrange to be off from school and not miss out on any duties. But the chair—and I can certainly understand it—doesn’t want the full-time faculty not to be there. We have the whole summer off and a big break in January. That’s true, but you can’t always plan your life that way. I’m seeing whether I can adjust. It’s a one-year contract, a renewable one-year contract, so I’m not bound. It is the best job in the world. Being a full-time faculty member at the NYU School of the Arts is a plum job. Everybody wants it.

What makes it that?

Because you can be in New York with a full-time job dancing, teaching the best students around. We have our pick of the litter. We auditioned three hundred and fifty students just this past spring.

For how many spots?

For something like eighty. Of those eighty, we’ll take maybe thirty. So there’s no teaching job that is better, but no tenure. They know they can get away with it. I’ll take it because it’s a good job. I was an adjunct at NYU for two years before this position came open. I just applied as a formality. Things snowballed and suddenly I had the job if I wanted it. I said, “Oh, okay.” I had never had a full-time job before.

You’ve always been independent?

I’ve always been a freelancer, yes. But I’m fifty-seven, the body doesn’t work like it used to, and you start thinking about how much you can do.

How do you keep yourself so fit? Is it dancing that did that?

I guess. In fact, I started doing gym ten years ago. I never did lift a weight or thought about lifting a weight or any of that aerobics stuff. Ten years ago I started doing that just to keep toned.

So that helped you?

Yes, a whole lot. It doesn’t matter how many dance classes you take, you don’t get the same benefit that you get from doing weight training and aerobics. It’s different and it’s necessary. When you’re young, you can get away with not doing it specifically. But now even the young dancers are doing it, and that’s why they’re so great. I’m still keeping my options open. I still have not performed as much as I want to in my life.

But now even the young dancers are doing it, and that’s why they’re so great. I’m still keeping my options open. I still have not performed as much as I want to in my life.

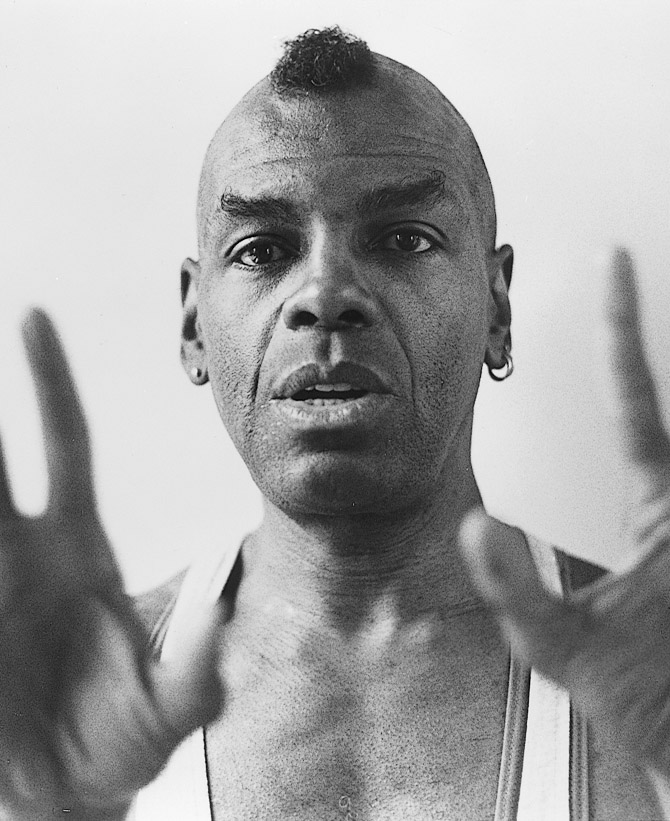

I worked with Martha Clarke. Do you know Martha Clarke? She’s one of the MacArthur “genius grant” recipients. The reason I got this mohawk hair-do was to do a piece of hers. She did The Magic Flute a couple of summers ago. I was the deus-ex-machina character. I loved working with her. It’s a way of performing that I don’t have to choreograph. She’s doing Marco Polo right now. That I would have been able to do if I had not been at NYU full time. So that shows you.

Did you also work a little bit with Alvin Ailey?

No, Donald McKayle. There were several of us— the black dancers—back in the ’60s and ’70s who danced with Donny and Alvin, or one or the other. I enjoyed working with Donny because I felt his work had more choreographic substance than Alvin’s. Donny’s still at it.

Let me come back just a little bit to the MIT experience. You had a special time when you were there, but if you had to summarize and analyze your perspective on your MIT experience, how would you do that? Then I want to ask you what advice you would give to young blacks coming to MIT, based on your experiences, not only at MIT.

I would summarize it, I think, by saying that the education—the training that I got at MIT in architecture—combined with the discipline I got in dance at the same time, made it possible for me to design a life that I have enjoyed without ever having to “get a job.” I think the knowledge combined with the discipline of working, not because someone was saying do it, has made my life as successful as it has been.

I think the advice I would give to anyone entering MIT is to learn who you are, while you’re learning what you want to be doing, because it’s the understanding of who you are that’s going to allow you to use the knowledge that you acquire.

I think the advice I would give to anyone entering MIT is to learn who you are, while you’re learning what you want to be doing, because it’s the understanding of who you are that’s going to allow you to use the knowledge that you acquire. That’s what makes wisdom. Knowledge is not wisdom. Information is not knowledge. You get lots of information at MIT and if you know how to process it, you get knowledge. Then, if you know who you are with this knowledge, you become wise.

As I said earlier, I think you are unique. I think you’ll find that when we put it together, you’ll see some very beautiful people who have come out of MIT like yourself. At the time you came through, you were unique. If there’s anything from any perspective—either your job experience, MIT, anything else—you think you would like to put on record, please do so.

I wish I were rich and famous.