Of Freud, 19th-Century Therapeutics, and Recumbent Posture

From the mid-19th century until the 1950s, when the advent of antibiotics revolutionized tuberculosis treatment, the primary treatment for the disease was the Luft-Liegekur, or open-air rest cure. It was in the sanatorium, according to the German physician Hermann Brehmer, that a strict regimen of diet, light exercise, outdoor exposure, and rest could successfully cure TB infection.

Both furniture makers and physicians capitalized on this “cure,” seeking numerous patents for improvements and variations upon the adjustable chaise-longue, a reclining chair with a long seat, and the schlafsofa, a sleep sofa that was a fixture of sanatoria throughout Europe and the U.S. and eventually became a medical icon throughout the West. As a physician who trained during a period when TB was a leading medical scourge, Sigmund Freud would have been steeped in the culture of the sanatorium and the Luft-Liegekur.

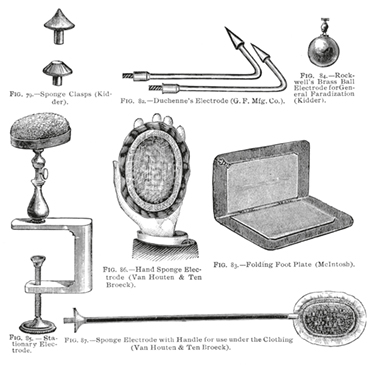

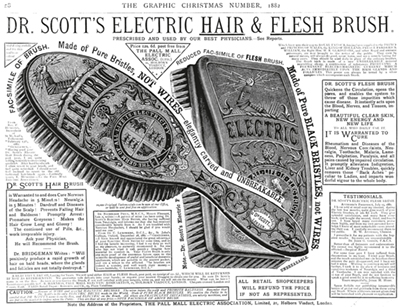

It’s no surprise, then, that along with hypnosis, Freud’s early forays into psychological medicine included the practice of treatments that sought to import ideals of comfort and healthy relaxation derived from the long dominance of the open-air rest cure. Among other practices, he employed massage and cutaneous electrotherapy, including the use of the faradic brush, an electric brush used to stimulate the skin.

“My therapeutic arsenal contained only two weapons, electrotherapy and hypnotism, for prescribing a visit to a hydropathic establishment after a single consultation was an inadequate source of income.”

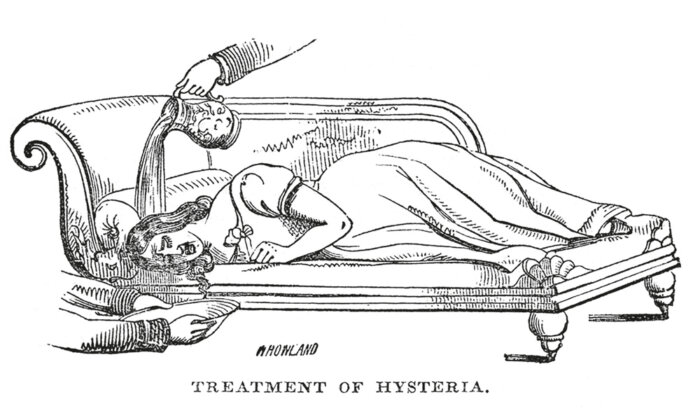

In “An Autobiographical Study,” Freud writes candidly that at the start of his clinical career, “My therapeutic arsenal contained only two weapons, electrotherapy and hypnotism, for prescribing a visit to a hydropathic establishment after a single consultation was an inadequate source of income.” He adds that his knowledge of electrotherapy was derived from neurologist Wilhelm Erb’s “Handbuch der Electrotherapie,” a work cited three times in the “Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud.” In an 1888 encyclopedia article on “hysteria,” meanwhile, Freud enthusiastically endorses the rest cure, consisting, as he describes it, of “isolation in absolute quiet with a systematic application of massage and general faradizations.”

Hydrotherapy and phototherapy, too, were traditional, asylum-based treatments for hysteria and other mental maladies that Freud, like all practitioners of his generation, was well aware of. The latter, which made use of ultraviolet irradiation, was considered an effective treatment for hysteria, epilepsy, neurasthenia, migraine, melancholia, mania, insomnia, and a wide variety of other psychiatric, neurological, and general medical disorders.

19th-century asylum keepers, psychologists, and university-based psychiatrists employed a host of somatic and suggestive therapies to treat these conditions. These therapies included hypnosis, hydrotherapy, cutaneous electrotherapy, phototherapy, diet and rest cures, massage, and, with the introduction of chemically prepared (as opposed to plant-derived) sedatives such as chloral hydrate in 1869, some early efforts at modern psychopharmacology. Since these treatment modalities (with the exception of psychopharmacology) usually required recumbent posture, it seems reasonable to infer that their popularity promoted an association in the minds of patients and practitioners alike between recumbence and cure. It would be glib to speak simply of submission to medical authority when many of these treatments sought to import ideals of domestic ease and comfort into the psychiatric setting.

“The germ of all life is electricity.”

Trance states were initially construed to be a form of “neurohypnotism” or “nervous sleep,” so it made sense for practitioners to have furniture suitable for reclining, sleeping, swooning, or becoming entranced while recumbent. During his 1885–1886 sojourn in Paris at the Salpêtrière Hospital, Freud learned about hypnosis in the treatment of hysteria from the world-famous neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot. Upon his return to Vienna, as he embarked upon the private practice of clinical neurology specializing in the treatment of nervous and mental disorders, Freud settled into a 10-year dalliance with hypnosis. At the height of Charcot’s rivalry with Hippolyte Bernheim in the 1880s and 1890s over suggestibility and the nature of hypnosis, Freud translated both men’s work into German and wrote prefaces to the three volumes of their writings he translated. Bernheim and his followers in the Nancy school of hypnotists, including August Forel, Leopold Löwenfeld, Oskar Vogt, and Otto Wetterstrand, emphasized the need for a calm, quiet environment for their treatments and encouraged patients to fall asleep during hypnotic sessions.

The private practice of German hypnosis doctors, among them some of the leading contributors to the Zeitschrift für Hypnotismus (Journal of Hypnotism), was dominated by this approach. This development coincided with the rise of office-based private practice in Germany and Austria, and the emergence of the tradition of the reserved office hour. Freud’s early practice of hypnosis was, in fact, modeled upon the Nancy school’s emphasis on recumbence and sleep.

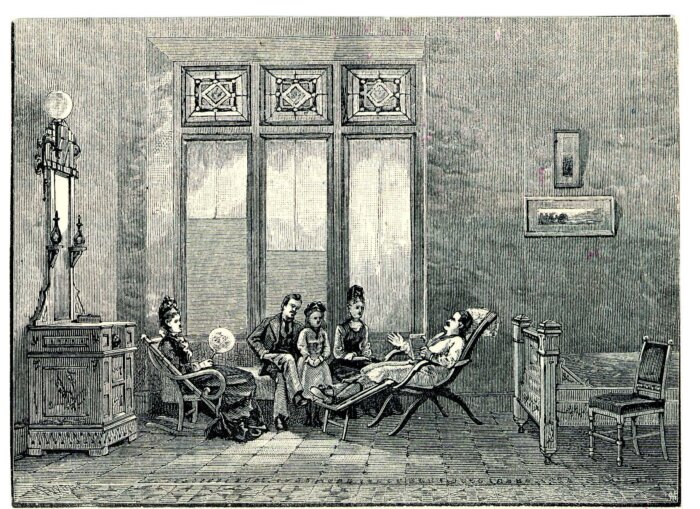

Thus, the use of recumbent posture in psychoanalysis evolved in part from these traditions of sanatorium- and asylum-based somatic therapies as well as from the broader cultural backdrop of changing notions of comfort and interiority, eventuating in what I call the medicalization of comfort. The illustration above nicely illustrates this point. In this image, published in Harper’s Magazine in 1878, the hospitalized patient is seen resting comfortably in a recliner that closely resembles the standard chaise-longue of the TB sanatorium. His concerned family members attend him in seated comfort, one of them in what appears to be a rocking chair. The scene is one of institutionalized domesticity. At least for the private patient, some trappings of the comforts of home accompany him during his hospital stay. His recumbent posture signifies how, by the time Freud began to develop his ideas about the optimal treatment setting for psychoanalysis, notions of healing and comfort had thoroughly melded.

Nathan Kravis is Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, where he is also Associate Director of the DeWitt Wallace Institute for the History of Psychiatry, and Training and Supervising Analyst at the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research. He is the author of “On the Couch,” from which this article is adapted.